Two hundred years ago, the greatest eruption in Earth’s recorded history took place. Mount Tambora—located on Sumbawa Island in the East Indies—blew itself up with apocalyptic force in April 1815.

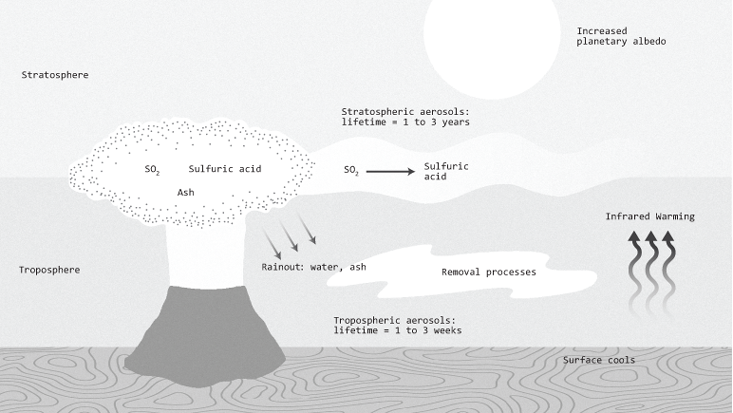

After perhaps 1,000 years’ dormancy, the devastating evacuation and collapse required only a few days. It was the concentrated energy of this event that was to have the greatest human impact. By shooting its contents into the stratosphere with biblical force, Tambora ensured its volcanic gases reached sufficient height to disable the seasonal rhythms of the global climate system, throwing human communities worldwide into chaos. The sun-dimming stratospheric aerosols produced by Tambora’s eruption in 1815 spawned the most devastating, sustained period of extreme weather seen on our planet in perhaps thousands of years.

Within weeks, Tambora’s stratospheric ash cloud circled the planet at the equator, from where it embarked on a slow-moving sabotage of the global climate system at all latitudes. Five months after the eruption, in September 1815, meteorological enthusiast Thomas Forster observed strange, spectacular sunsets over Tunbridge Wells near London. “Fair dry day,” he wrote in his weather diary—but “at sunset a fine red blush marked by diverging red and blue bars.”

Artists across Europe took note of the changed atmosphere. William Turner drew vivid red skyscapes that, in their coloristic abstraction, seem like an advertisement for the future of art. Meanwhile, from his studio on Greifswald Harbor in Germany, Caspar David Friedrich painted a sky with a chromic density that—one scientific study has found—corresponds to the “optical aerosol depth” of the colossal volcanic eruption that year.

For three years following Tambora’s explosion, to be alive, almost anywhere in the world, meant to be hungry. In New England, 1816 was nicknamed the “Year Without a Summer” or “Eighteen-Hundred-and-Froze-to-Death.” Germans called 1817 the “Year of the Beggar.” Across the globe, harvests perished in frost and drought or were washed away by flooding rains. Villagers in Vermont survived on porcupine and boiled nettles, while the peasants of Yunnan in China sucked on white clay. Summer tourists traveling in France mistook beggars crowding the roads for armies on the march.

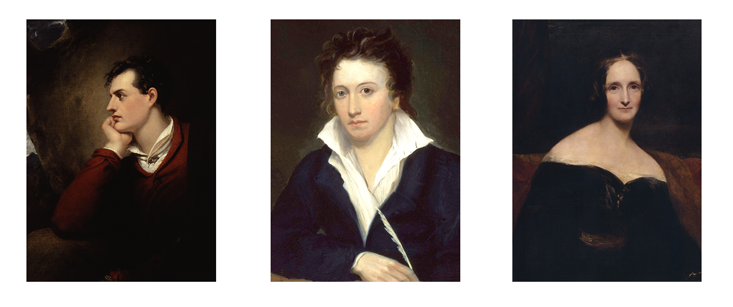

One such group of English tourists, at their lakeside villa near Geneva, passed the cold, crop-killing days by the fire exchanging ghost stories. Mary Shelley’s storm-lashed novel Frankenstein bears the imprint of the Tambora summer of 1816, and her literary coterie—which included the poets Percy Shelley and Lord Byron—serve as tour guides through the suffering worldscape of 1815–18.

Considered on a geological timescale, Tambora stands almost insistently near to us. The Tambora climate emergency of 1815–18 offers us a rare, clear window onto a world convulsed by weather extremes, with human communities everywhere struggling to adapt to sudden, radical shifts in temperatures and rainfall, and a flow-on tsunami of famine, disease, dislocation, and unrest. It is a case study in the fragile interdependence of human and natural systems.

On Sumbawa Island, the beginning of the dry season in April 1815 meant a busy time for the local farmers. In a few weeks the rice would be ready, and the raja of Sanggar, a small kingdom on the northeast coast of the island, would send his people into the fields to harvest. Until then, the men of his village, called Koreh, continued to work in the surrounding forests, chop- ping down the sandalwood trees vital to shipbuilders in the busy sea lanes of the Dutch East Indies.

On the evening of April 5, 1815, at about the time his servants would have been clearing the dinner dishes, the raja heard an enormous thunderclap. Perhaps his first panicked thought was that the beach lookout had fallen asleep and allowed a pirate ship to creep in to shore and fire its cannon. But everyone was instead staring up at Mount Tambora. A jet of flame burst skyward from the summit, lighting up the darkness and rocking the earth beneath their feet. The noise was incredible, painful.

Huge plumes of flame issued from the mountain for three hours, until the dark mist of ash became confused with the natural darkness, seeming to announce the end of the world. Then, as suddenly as it had begun, the column of fire collapsed, the earth stopped shaking, and the bone-jarring roars faded. Over the next few days, Tambora continued to bellow occasionally, while ash drifted down from the sky.

Meanwhile to the southeast in the capital Bima, colonial administrators were sufficiently alarmed by the events of April 5 to send an official, named Israel, to investigate the emergency situation at the volcano, on the Sanggar Peninsula. By April 10, the man’s bureaucratic zeal had led him to the very slopes of Tambora. There, in the dense tropical forest, at about 7 p.m., he became one of the first victims of the most powerful volcanic eruption in recorded history.

Within hours, the village of Koreh, along with all other villages on the Sanggar Peninsula, ceased to exist entirely, a victim of Tambora’s spasm of self-destruction. This time three distinct columns of fire burst in a cacophonous roar from the summit to the west, blanketing the stars and uniting in a ball of swirling flame at a height greater than the eruption of five days before. The mountain itself began to glow as streams of boiling liquefied rock coursed down its slopes. At 8 p.m., the terrifying conditions across Sanggar grew worse still, as a hail of pumice stones descended, mixed with a downpour of hot rain and ash.

On the northern and western slopes of the volcano, whole villages, totaling perhaps 10,000 people, had already been consumed within a vortical hell of flames, ash, boiling magma, and hurricane-strength winds. In 2004, an archaeological team from the University of Rhode Island uncovered the first remains of a village buried by the eruption: a single house under three meters of volcanic pumice and ash. Inside the walled remains, they found two carbonized bodies, perhaps a married couple. The woman, her bones turned to charcoal by the heat, lay on her back, arms extended, holding a long knife. Her sarong, also carbonized, still hung across her shoulder.

The Tambora climate emergency offers us a rare, clear window onto a world convulsed by weather extremes. It is a case study in the fragile interdependence of human and natural systems.

Back on the mountain’s eastern flank, the rain of volcanic rocks gave way to ashfall, but there was to be no relief for the surviving villagers. The spectacular, jet-like “plinian” eruption (named for Pliny the Younger, who left a famous account of Vesuvius’s vertical column of fire) continued unabated, while glowing, fast-moving currents of rock and magma, called “pyroclastic streams,” generated enormous phoenix clouds of choking dust. As these burning magmatic rivers poured into the cool sea, secondary explosions redoubled the aerial ash cloud created by the original plinian jet. An enormous curtain of steam and ash clouds rose and encircled the peninsula, creating, for those trapped inside it, a short-term microclimate of pure horror.

First, a “violent whirlwind” struck Koreh, blowing away roofs. As it gained in strength, the volcanic hurricane uprooted large trees and launched them like burning javelins into the sea. Horses, cattle, and people alike flew upward in the fiery wind. What survivors remained then faced another deadly element: giant waves from the sea. The crew of a British ship cruising offshore in the Flores strait, coated with ash and bombarded by volcanic rocks, watched stupefied as a 12-foot-high tsunami washed away the rice fields and huts along the Sanggar coast. Then, as if the combined cataclysms of air and sea weren’t enough, the land itself began to sink as the collapse of Tambora’s cone produced waves of subsidence across the plain.

On the sunless days following the cataclysm, corpses lay unburied all along the roads on the inhabited eastern side of the island between Dompu and Bima. Villages stood deserted, their surviving inhabitants having scattered in search of food. With forests and rice paddies destroyed, and the island’s wells poisoned by volcanic ash, some 40,000 islanders would perish from sickness and starvation in the ensuing weeks, bringing the estimated death toll from the eruption to over 100,000, the largest in history.

While the skyward eruptions lasted only about three hours each, the boiling cascade of pyroclastic streams down Tambora’s slopes continued a full day. Hot magma gushed from Tambora’s collapsing chamber down to the peninsula, while columns of ash, gas, and rock rose and fell, feeding the flow. The fiery flood that consumed the Sanggar Peninsula, traveling up to 19 miles at great speeds, ultimately extended over a 216-square-mile area, one of the greatest pyroclastic events in the historical record. Within a few short hours, it buried human civilization in northeast Sumbawa under a smoking meter-high layer of ignimbrite.

Tambora’s cacophony of explosions on April 10, 1815, could be heard hundreds of miles away. All across the region, government ships put to sea in search of imaginary pirates and invading navies. In the seas to the north off Macassar, the captain of the East India Company vessel Benares gave a vivid account of conditions in the region on April 11:

The ashes now began to fall in showers, and the appearance altogether was truly awful and alarming. By noon, the light that had remained in the eastern part of the horizon disappeared, and complete darkness had covered the face of day … The darkness was so profound throughout the remainder of the day, that I never saw anything equal to it in the darkest night; it was impossible to see your hand when held up close to the eye.

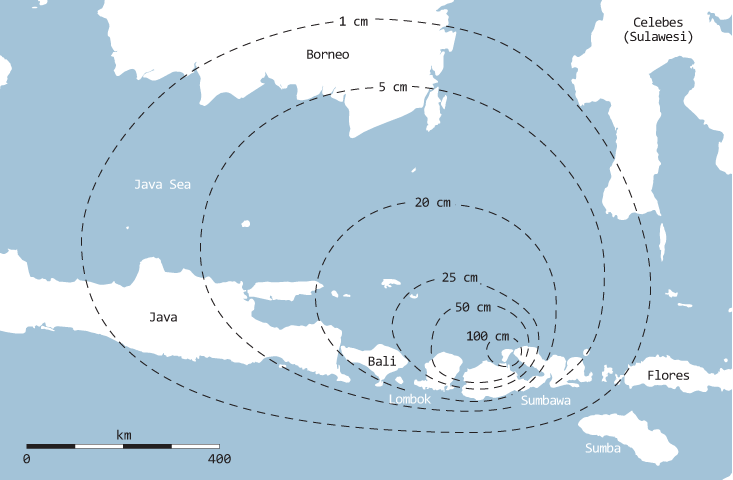

Across a 600-kilometer radius, darkness descended for two days, while Tambora’s ash cloud expanded to cover a region nearly the size of the continental United States. The entire Southeast Asian region was blanketed in volcanic debris for a week. Day after dark day, British officials conducted business by candlelight, as the death toll mounted.

Months after the eruption, the atmosphere remained heavy with dust—the sun a blur. Drinking water contaminated by fluorine-rich ash spread disease and with 95 percent of the rice crop in the field at the time of the eruption, the threat of starvation was immediate and universal. In their desperation for food, islanders were reduced to eating dry leaves and their much-valued horseflesh. By the time the acute starvation crisis was over, Sumbawa had lost half its population to famine and disease, while most of the rest had fled to other islands.

Tambora’s violent impact on global weather patterns was due, in part, to the already unstable conditions prevailing at the time of its eruption. A major tropical volcano had blown up six years prior, in 1809. This cooling event, hugely amplified by the sublime Tambora eruption in 1815, ensured extreme volcanic weather across the entire decade.

A flurry of research since the discovery of the 1809 eruption has resulted in the identification of the 1810–19 decade as a whole as the coldest in the historical record—a gloomy distinction. A 2008 modeling study concluded Tambora’s eruption to have had by far the largest impact on global mean surface air temperatures among volcanic events since 1610, while the 1809 volcano ranked second over that same period, measuring just over half Tambora’s decline. Two papers published the following year confirmed the status of the 1810s as “probably the coldest during the past 500 years or longer,” a fact directly attributable to the proximity of the two major tropical eruptions.

The spectacular eruption increased that cooling to a truly dire extent, contributing to an overall decline of global average temperatures of 1.5 degrees Celsius across the decade. One-and-a-half degrees might seem a small number, but as a sustained decline characterized by a sharp rise in extreme weather events—floods, droughts, storms, and summer frosts—the chilled global climate system of the 1810s had devastating impacts on human agriculture, food supply, and disease ecologies.

The Scottish meteorologist George Mackenzie kept meticulous records of cloudy skies between 1803 and 1821 over various parts of the British Isles. Where lovely clear summer days in the earlier period (1803–10) averaged over 20, in the volcanic decade (1811–20) that figure dropped to barely five. For 1816, the Year Without a Summer, Mackenzie recorded no clear days at all.

On the eve of the summer of 1816, 18-year-old Mary Godwin took flight with her lover, Percy Shelley, and their baby for Switzerland, escaping the chilly atmosphere of her father’s house in London. Mary’s young stepsister, Claire Clairmont, accompanied them, eager to reunite with her own poet-lover, Lord Byron, who had left England for Geneva a week earlier. Mary’s other sister, the ever dispensable Fanny, was left behind.

The dismal, often terrifying weather of the summer of 1816 is a touchstone of the ensuing correspondence between the sisters. In a letter to Fanny, written on her arrival in Geneva, Mary describes their ascent of the Alps “amidst a violent storm of wind and rain.” The cold was “excessive” and the villagers complained of the lateness of the spring. On their alpine descent days later, a snowstorm ruined their view of Geneva and its famous lake. In her return letter, Fanny expresses sympathy for Mary’s bad luck, reporting that it was “dreadfully dreary and rainy” in London too, and very cold.

Stormy nor’easters are standard features of Genevan weather in summertime, careening from the mountains to whip the waters of the lake into a sirocco of foam. Beginning in June 1816, these annual storms attained a manic intensity not witnessed before or since. “An almost perpetual rain confines us principally to the house,” Mary wrote to Fanny on the first of June from Maison Chappuis, their rented house on the shores of Lake Geneva: “One night we enjoyed a finer storm than I had ever before beheld. The lake was lit up—the pines on Jura made visible, and all the scene illuminated for an instant, when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads amid the darkness.” A diarist in nearby Montreux compared the bodily impact of these deafening thunderclaps to a heart attack.

In fact, the year 1816 remains the coldest, wettest Geneva summer since records began in 1753. That unforgettable year, 130 days of rain between April and September swelled the waters of Lake Geneva, flooding the city. Up in the mountains the snow refused to melt. Clouds hung heavy, while the winds blew bitingly cold. In some parts of the inundated city, transport was only possible by boat. A cold northwest wind from the Jura mountains—called le joran by locals—swept relentlessly across the lake. The Montreux diarist called the persistent snows and le joran “the twin evil genies of 1816.” Tourists complained they couldn’t recognize the famously picturesque landscape because of the constant wind and avalanches, which drove snow across vast areas of the plains.

On the night of June 13, 1816, the Shelleys’ splendidly domiciled neighbor, Lord Byron, stood out on the balcony of the lakeside Villa Diodati to witness “the mightiest of the storms” that he—well-traveled aristocrat that he was—had ever seen. He memorialized that tumultuous night in his wildly popular poem “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”:

The sky is changed—and such a change! Oh night,

And storm, and darkness, ye are wondrous strong …

And now again ’tis black,—and now, the glee

Of the loud hills shakes with its mountain-mirth,

As if they did rejoice o’er a young earthquake’s birth.

In Byron’s imagination, the Tamboran storms of 1816 achieve volcanic dimensions—like an “earthquake’s birth”—and take delight in their destructive power.

What caused the terrible weather conditions over Britain and western Europe in 1816–18? The relation between volcanism and climate depends on eruptive scale. Volcanic ejecta and gases must penetrate skyward high enough to reach the stratosphere where, in its cold lower reaches, sulfate aerosols form. These then enter the meridional currents of the global climate system, disrupting normal patterns of temperature and precipitation across the hemispheres. Tambora’s April 1815 eruption launched enormous volumes of long-suppressed volcanic rock and gases more than 25 miles into the stratosphere. This volcanic plume—consisting of as much as 12 cubic miles of total matter—eventually spread across 386,000 square miles of the Earth’s atmosphere, an aerosol umbrella six times the size of the cloud produced by the massive 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines.

In the first weeks after Tambora’s eruption, a vast volume of coarser ash particles—volcanic “dust”—cascaded back to Earth mixed with rain. But ejecta of smaller size—water vapor, molecules of sulfur and fluorine gases, and fine ash particles—remained suspended in the stratosphere, where a sequence of chemical reactions resulted in the formation of a 60-mega- ton sulfate aerosol layer. Over the following months, this dynamic, streamer-like cloud of aerosols—much smaller in size than the original volcanic matter—expanded by degrees to form a molecular screen of planetary scale, spread aloft by the winds and meridional currents of the world. In the course of an 18-month journey, it passed across both south and north poles, leaving a telltale sulfate imprint on the ice for paleo-climatologists to discover more than a century and a half later.

Once settled in the dry firmament of the stratosphere, Tambora’s global veil circulated above the weather dynamics of the atmosphere, comfortably distanced from the rain clouds that might have dispersed it. From there, its planet-girdling aerosol film continued to scatter shortwave solar radiation back into space until early 1818, while allowing much of the longwave radiant heat from the earth to escape. The resultant three-year cooling regime, unevenly distributed by the currents of the world’s major weather systems, barely affected some places on the globe (Russia, for instance, and the trans-Appalachian United States) but precipitated a drastic 5 to 6 degrees Fahrenheit seasonal decline in other regions, including Europe.

The first extreme impact of a major tropical eruption is felt in raw temperature. But in western Europe, biblical-style inundation during the 1816 summer growing season wrought the greatest havoc. Because of the tilt of the Earth in relation to the sun and the different heat absorption rates of land and sea, solar insolation of the planet is irregular. Uneven heating in turn creates an air pressure gradient across the latitudes of the globe. Wind is the weatherly expression of these temperature and pressure differentials, transporting heat from the tropics to the poles, moderating temperature extremes, and carrying evaporated water from the oceans over the land to support plant and animal life. The major meridional circulation patterns, measuring thousands of miles in breadth, transport energy and moisture horizontally across the globe, creating continental-scale weather patterns. Meanwhile, at smaller scales, the redistribution of heat and moisture through the vertical column of the atmosphere produces localized weather phenomena, such as thunderstorms.

Tambora’s influence on human history does not derive from extreme weather events considered in isolation but in the myriad environmental impacts of a climate system gone haywire.

In the summer after Tambora’s eruption, however, the aerosol loading of the stratosphere heated the upper layer, which bore down upon the atmosphere. The “tropopause” that marks the ceiling of the Earth’s atmosphere dropped lower, cooling air temperatures and displacing the jet streams, storm tracks, and meridional circulation patterns from their usual course. By early 1816, Tambora’s chilling envelope had created a radiation deficit across the North Atlantic, altering the dynamics of the vital Arctic Oscillation. Slower-churning warm waters north of the Azores pumped over-loads of moisture into the atmosphere, saturating the skies while enhancing the temperature gradient that fuels wind dynamics. Meanwhile, air pressure at sea level plummeted across the mid-latitudes of the North Atlantic, dragging cyclonic storm tracks southward. Pioneering British climate historian Hubert Lamb has calculated that the influential Icelandic low-pressure system shifted several degrees latitude to the south during the cold summers of the 1810s compared to 20th-century norms, settling in the unfamiliar domain of the British Isles, and thus ensuring colder, wetter conditions for all of western Europe.

Both computer models and historical data draw a dramatic picture of Tambora-driven storms hammering Britain and western Europe. A recent computer simulation conducted at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado showed fierce westerly winds in the North Atlantic in the aftermath of a major tropical eruption, while a parallel study based on multiproxy reconstructions of volcanic impacts on European climate since 1500 concluded that volcanic weather drives the increased “advection of maritime air from the North Atlantic,” meaning “stronger westerlies” and “anomalously wet conditions over Northern Europe.”

Back at the ground level of observed weather phenomena, an archival study of Scottish weather has found that, in the 1816–18 period, gale-force winds battered Edinburgh at a rate and intensity unmatched in over 200 years of record keeping. In January 1818, a particularly violent storm nearly destroyed the beloved St. John’s Chapel in the heart of the city. The slowing of oceanic currents in response to the overall deficit of solar radiation post-Tambora had left unusual volumes of heated water churning through the critical area between Iceland and the Azores, sapping air pressure, energizing westerly winds, and giving shape to titanic storms.

It was in this literally electric atmosphere that the Shelley party in Geneva, with Byron attached, conceived the idea of a ghost story contest, to entertain themselves indoors during this cold, wild summer. On the night of June 18, 1816, while another volcanic summer thunderstorm raged around them, Mary and Percy Shelley, Claire Clairmont, Byron, and Byron’s doctor-companion John Polidori recited the poet Coleridge’s recent volume of gothic verse to each other in the candlelit dimness at the Villa Diodati. In his 1986 movie about the Shelley circle that summer, British film director Ken Russell imagines Shelley gulping tincture of opium while Claire Clairmont performs fellatio on Byron, recumbent in a chair. Group sex in the drawing room might be implausible, even for the Shelley circle, but drug taking is very likely, inspired by Coleridge, the poet-addict supreme. How else to explain Shelley’s running screaming from the room at Byron’s recitation of the psychosexual “Christabel,” tormented by his vision of a bare-chested Mary Shelley with eyes instead of nipples?

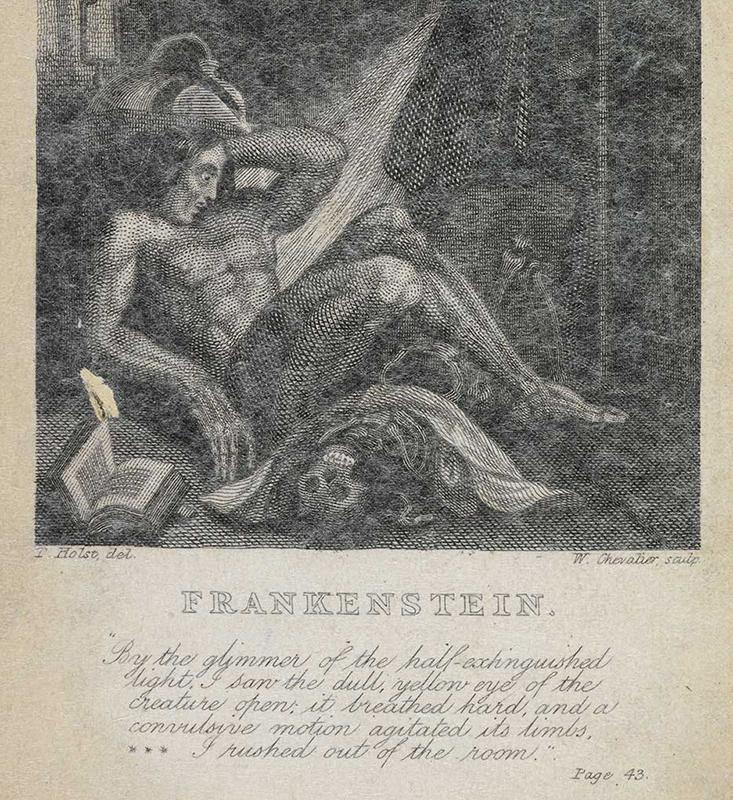

From such antics, Byron conceived the outline of a modern vampire tale, which the bitter Polidori would later appropriate and publish under Byron’s name as a satire on his employer’s cruel aristocratic hauteur and sexual voracity. For Mary, the lurid events of this stormy night gave literary body to her own distracted musings on the ghost story competition, instituted two nights earlier. She would write a horror story of her own, about a doomed monster brought unwittingly to life during a storm. As Percy Shelley later wrote, the novel itself seemed generated by “the magnificent energy and swiftness of a tempest.” Thus it was that the unique creative synergies of this remarkable group of college-age tourists—in the course of a few weeks’ biblical weather—gave birth to two singular icons of modern popular culture: Frankenstein’s monster and the Byronic Dracula.

A week after the memorable night of June 18, Byron and Shelley almost came to grief sailing on Lake Geneva, caught unawares as another violent storm swept in from the east. “The wind gradually increased in violence,” Shelley recalled, “until it blew tremendously; and, as it came from the remotest extremity of the lake, produced waves of a frightful height, and covered the whole surface with a chaos of foam.” By some miracle they found a sheltered port, where even the storm-hardened locals exchanged “looks of wonder.” Onshore, trees had blown down or been shattered by lightning.

The pyrotechnical lightning displays of June 1816 ignited the literary imagination of Mary Shelley. In Frankenstein, she uses the experience of a violent thunderstorm as the scene of fateful inspiration for her young, doomed scientist:

When I was about fifteen years old … we witnessed a most violent and terrible thunderstorm. It advanced from behind the mountains of Jura; and the thunder burst at once with frightful loudness from various quarters of the heavens. I remained, while the storm lasted, watching its progress with curiosity and delight. As I stood at the door, on a sudden I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak, which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump.

Frankenstein’s life is changed in this moment; he devotes himself, with maniacal energy, to the study of electricity and galvanism. In the fierce smithy of that Tamboran storm, Frankenstein is born as the anti-superhero of modernity—the “Modern Prometheus”—stealer of the gods’ fire.

Tambura’s influence on human history does not derive from extreme weather events considered in isolation but in the myriad environmental impacts of a climate system gone haywire. As a result of the prolonged poor weather, crop yields across the British Isles and western Europe plummeted by 75 percent and more in 1816–17. In the first summer of Tambora’s cold, wet, and windy regime, the European harvest languished miserably. Farmers left their crops in the field as long as they dared, hoping some fraction might mature in late-coming sunshine. But the longed-for warm spell never arrived and at last, in October, they surrendered. Potato crops were left to rot, while entire fields of barley and oats lay blanketed in snow until the following spring.

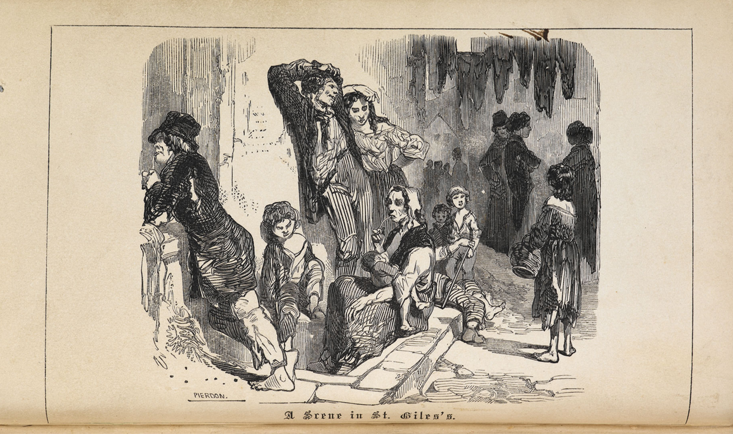

In Germany, the descent from bad weather to crop failure to mass starvation conditions took a frighteningly rapid course. Carl von Clausewitz, the military tactician, witnessed “heartrending” scenes on his horseback travels through the Rhine country in the spring of 1817: “I saw decimated people, barely human, prowling the fields for half-rotten potatoes.” In the winter of 1817, in Augsburg, Memmingen, and other German towns, riots erupted over the rumored export of corn to starving Switzerland, while the locals were reduced to eating horse and dog flesh.

Meanwhile, back in England, riots broke out in the East Anglian counties as early as May 1816. Armed laborers bearing flags with the slogan “Bread or Blood” marched on the cathedral town of Ely, held its magistrates hostage, and fought a pitched battle against the militia.

In his magisterial account of the social and economic upheaval in Europe during the Tambora period, historian John Post has shown the scale of human suffering to be worst in Switzerland, home to Shelley and her circle in 1816. Even in normal times, a Swiss family devoted at least half its income to buying bread. Already by August 1816, bread was scarce, and in December, bakers in Montreux threatened to cease production unless they could be allowed to raise prices. With imminent famine came the threat of “soulèvements”: violent uprisings. Bakers were set upon by starving mobs in the market towns and their shops destroyed. The English ambassador to Switzerland, Stratford Canning, wrote to his prime minister that an army of peasants, unemployed and starving, was assembling to march on Lausanne.

Most shocking of all was the fate of some desperate mothers. In horrific circumstances repeated around the world in the Tambora period, some Swiss families abandoned their offspring in the crisis, while others chose killing their children as the more humane course. For this crime, some starving women were apprehended and decapitated. Thousands of Swiss with more means and resilience emigrated east to prosperous Russia, while others set off along the Rhine to Holland and sailed from there to North America, which witnessed its first significant wave of refugee European migration in the 19th century. The numbers of European immigrants arriving at U.S. ports in 1817 more than doubled the number of any previous year.

Devastated by famine and disease in the Tambora period, the poor of Europe hurriedly buried their dead before resuming the bitter fight for their own survival. In the worst cases, children were abandoned by their families and died alone in the fields or by the roadside. The well-born members of the Shelley circle were never reduced to such abysmal circumstances. They did not experience the food crises that afflicted millions among the rural populations of western Europe in the Tambora period. Yet the Shelleys’ celebrated writings were enmeshed within the web of ecological breakdown following the Tambora eruption.

Byron and Percy Shelley were companions on a weeklong walking tour of Alpine Switzerland in June 1816, during which they debated poetry, metaphysics, and the future of mankind but also found time to remark on the village children they encountered, who “appeared in an extraordinary way deformed and diseased. Most of them were crooked, and with enlarged throats.” In Frankenstein, the Doctor’s benighted creation assumes a similar grotesque shape: a barely human creature, deformed, crooked, and enlarged. Like the hordes of refugees on the roads of Europe seeking aid in 1816–18, the Creature, when he ventures into the towns, is met with fear and hostility, horror and abomination. As the indigent Creature himself puts it, he suffered first “from the inclemency of the season” but “still more from the barbarity of man.”

As remarkable a feat of literary imagination as Frankenstein is, Mary Shelley was not wanting for real-world inspiration for her horror story, namely the deteriorating rural populations of Europe, in the climatic upheaval of Mount Tambora.

Gillen D’Arcy Wood is the Robert W. Schaefer Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of the award-winning Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World, Land of Wondrous Cold: The Race to Discover Antarctica and Unlock the Secrets of Its Ice, and most recently, The Wake of HMS Challenger: How a Legendary Victorian Voyage Tells the Story of Our Oceans’ Decline.

Excerpted from Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World by Gillen D’Arcy Wood. Copyright @ 2014 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.