In 2011, a friend of mine in college asked me if I’d read The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, by Jonathan Haidt. Haidt’s aim was to probe and distill—and “savor”—the moral precepts of antiquity in the light of modern science. The 2006 book was an answer to an overabundance of too-little-appreciated advice. “We might have already encountered the Greatest Idea, the insight that would have transformed us had we savored it, taken it to heart, and worked it into our lives,” Haidt wrote. My friend was happy to encounter it: Haidt helped him through a difficult breakup.

I hadn’t heard of the book, but I had heard of its author. A paper of Haidt’s, “The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment,” had been assigned in my moral psychology course, and I was in the middle of writing an essay that argued against its conclusion. Haidt wrote that reason, compared to emotion, typically matters little to what we believe is right or wrong. The idea that feelings like disgust, as opposed to deliberation, tend to play a more powerful role in driving what we deem ethical was, to me, an aspiring philosopher that prized rationality, distasteful. Those were the days …

I believe that if you really want to make a difference in the world, you need to commit to really studying the world.

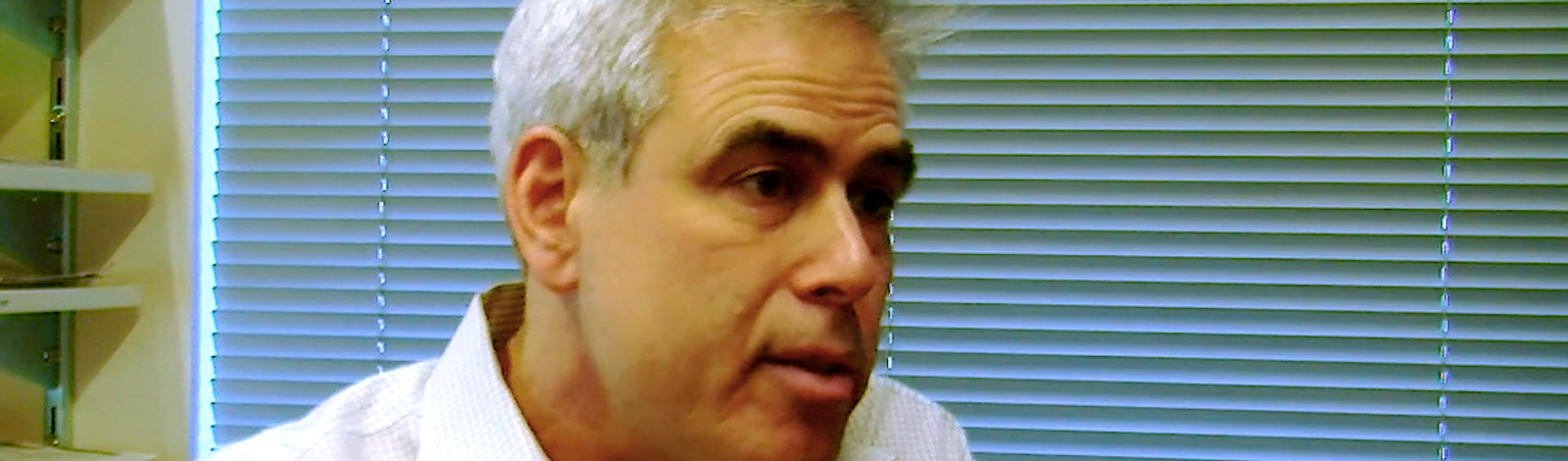

Haidt, meanwhile, was about to put out his next book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. In recent a conversation with Nautilus, at his office in the NYU Stern School of Business, Haidt said he began writing the book after George W. Bush won the United States presidential election. He was determined to help the Democrats win. “Liberalism seemed so obviously ethical,” he wrote. His research led him to an awakening. “Once I actually started reading the best conservative writing, going back to Edmund Burke and Michael Oakeshott in the 20th century, and Thomas Sowell more recently, and then libertarians,” he said, “I realized, Wow, you actually need to expose yourself to critics, to people who start from a different position.” The result was his “moral foundations” theory—roughly, there’s more to morality than the liberal emphasis on harm and fairness—which led Haidt to identify with no political tribe. He now defines himself as a centrist.

Which brings us to his latest salvo, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, co-authored with Greg Lukianoff, the president and CEO of F.I.R.E., the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. It is a kind of culmination of, or epilogue to, the ideas Haidt wrote about in his first two books. In The Coddling of the American Mind, Haidt and Lukianoff look at the fraught climate on elite college campuses and the effect that social media and paranoid parenting, among other things, have had on generation Z, or i-Gen, the most recent cohort (born post-1995) after the millennials. Some of the chapters in the book, for example, go by names like “The Search for Wisdom,” “The Polarization Cycle,” and “The Quest for Justice.” It is, in part, an anatomy of the psychology of activism.

During his interview with Nautilus, Haidt described his thoughts on these contentious topics with both care and gusto. (Disclosure: I serve as communications director at Ethical Systems, a research group formed by Haidt, housed at NYU.) Our talk ventured from his sizing-up of the “intellectual dark web” to his notes on New Atheism, his reaction to the “grievance studies” hoax, and the parenting advice he has for new fathers, like me. The public intellectual brought his A-game.1

Has something gone wrong with our conception of social justice?

Social justice has many meanings. I think the term was used [to refer to] a Catholic social justice in the 19th century. Some people, on the right especially, claim that the term is meaningless, that there’s only justice. I think that’s not right. I think that there are certain conceptions of justice that are about groups in society; and especially when groups are shut out or treated with lack of dignity, then I think talking about social justice as a particular subset of justice is useful.

What I’ve observed on campus—and what Greg Lukianoff and I wrote about in our book—is that there’s an increasing tendency to define, to look at any place where there’s not numerical parity, where any group is underrepresented relative to the population and to say, “that is unjust.” And any social scientist who’s thinking in any other domain would say, “well, no, wait a second. You have to know the pipeline. You have to know how many people were trying to get in, were people treated differently because of their group membership?”

In fact, just today, The New York Times announced that it’s going to commit to publishing an equal number of letters from men and women, even though 75 percent of the letter writers are men. Men like to put themselves out in public and show off. But The New York Times has committed to this equal outcomes social justice, which says we’re gonna treat people unequally in order to attain equal outcomes.

That I think is unfair. Most Americans think it’s unfair. Most Americans think that you should treat people as individuals and not discriminate against anyone because of their race or gender. So yes, we are in the middle of a time in which many people who call themselves social justice activists are trying to achieve policies that most people think will treat individuals unfairly.

How should we understand the concept of intersectionality?

Intersectionality is a very important concept on campus these days and it starts with an insight that I think is important and absolutely right. Which is that the experience of any person is not just the sum of the experiences of the various identities. So to be a black woman in American today is not just the sum of what it’s like to be a woman added on to what it’s like to be black. So Kimberle Crenshaw, the woman who popularized the concept and developed it, makes the point that there are distinctive indignities that black women would face that might not be faced by women or by black men let’s say.

So if the point is just that identities intersect or interact, it’s absolutely right. You can’t argue that. Where it’s gone wrong I believe is that it has become such a part of teaching on campus, it becomes wedded to a notion of society as a matrix of oppression in which young people learn to see society as being composed of all kinds of binary distinctions where the people on top are powerful and therefore bad. They are oppressors so they are morally bad. People on the bottom are the victims and therefore morally good.

Now of course oppression is bad, but to teach young people whose minds are … human minds evolved to do tribalism. We evolved to do us versus them, binary thinking, black and white thinking, good versus evil. To take 18-year-olds, and rather than try to turn that down and say “okay hold on, don’t be so moralistic. Let’s try to give people a chance. Let’s judge people as individuals.” That was the great achievement of the 20th century—to make progress there. Instead in the 21st century to say, “okay welcome to campus. Here are five or six dimensions; we’re going to teach you to see men, maleness, masculinity as bad, everyone else is good. White is bad, everyone else is good. Straight is bad, everyone else is good.” This is Manicheism. This is ramping up our tendency to dualistic thinking.

How did this sort of dualistic thinking that students are learning gain purchase in the academy?

Within each school, there are discrete departments that have a lot of autonomy. Deans and presidents can’t really tell departments what to teach or who to hire. So each department, each field in the academy evolves over the course of decades according to its own logic and the logic of its broader field outside of the university.

So I think that there are certain fields that are colloquially called the grievance studies departments. Fields that are not focused on doing basic research or on understanding social dynamics, but on activism, on changing social dynamics. In general, trying to change things and trying to understand them don’t go well together. The mission of a university I believe should be to understand. And if you do a great job of research, that can be the basis for all kinds of activism later. But if you start with a commitment to a certain way of seeing the world, and you start with a belief that some people are good and some people are bad, I think it makes it very hard to understand real social systems.

I think that there are certain areas, certain departments, certain majors that have more of an activist flavor than a research flavor. Students who major in those departments—I mean students get a lot of different experiences—but those who major in those departments and tend to socialize with people who think that way may come out of the university less wise than when they went in.

How should students leaving college think about trying to advance social justice?

Many students come to college with a dream or desire or goal of making the world a better place. This is an aspect of post-materialist societies: Prosperity, and general peace lead people to care more about women’s rights, gay rights, animal rights, the environment. This is a trend that happens all over the world. It’s happening in Asia as well. So increasingly students want to make a different in the world in a certain way in terms of social justice-type concerns. And that would be great if they were to commit to understanding first. If they would commit to understanding institutions first before they try to change them, then they’d have some success.

Unfortunately, social institutions are incredibly complicated and difficult to change. If you get a group of 20 top experts to study poverty let’s say, or child abuse or anything else, it’s often very difficult to really find a solution. It can take years of study. We then roll out programs, and it often turns out that the programs backfire. So I think that college students, if they really want to make a difference in the world, they should not become activists in their freshman year. They should devote themselves to studying and learning, and maybe by senior year, if they’re really expert in something, maybe they could get behind it.

Now there is one nice exception. The students at Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, they did a wonderful job of reviewing the research on gun control. Because, it’s a much harder problem than many people think. They really researched it, they came up with a set of recommendations that I read and I thought, “wow, this is really well informed. This is great.” And then they went to the legislature and tried to put pressure on them to pass those reforms. That’s the way to do it.

Unfortunately, what we have on campus often is certain popular ideas that have no empirical support: mandatory diversity training, more ethnic identity centers, bias response teams so that anybody can report anybody else anonymously. These might sound good to some people, but there’s no evidence that they’ll make a more inclusive, open, trusting environment. And there’s sometimes evidence that they’ll make things worse. So I believe that if you really want to make a difference in the world, you need to commit to really studying the world. Don’t get caught up in a group that is so passionate and so committed that it’s going to basically be blind to counter evidence.

Tell us the six explanatory threads that make up your book, The Coddling of the American Mind.

So in The Coddling of the American Mind, my co-author Greg Lukianoff and I are trying to figure out why campus culture changed so rapidly. Not everywhere—not even at most schools—but at most of the elite schools in the northeast and the west coast and elsewhere. Why was there suddenly this huge influx of these new ideas about safe spaces, microaggressions, trigger warnings, speech is violent, protect us from this violent speaker. Greg runs the foundation for individual rights in education. He’s always been trying to protect student free speech rights. And suddenly in 2014, students themselves were saying ban this, protect us from that, that’s violent, shut that down. And they were talking about safety. And they meant emotional safety. Where did this come from?

So Greg and I dug into it for several years, and what we came up with in our book—we’re very proud of—is a kind of social science detective story. We don’t say, “oh it’s all social media. Or oh it’s …”—it’s no one thing. So in the book, we show that there are at least six intersecting or interacting threads.

The rise in polarization of the country, as left and right hate each other more and more every year since the 1990s. There’s much more of an impetus to yell and scream, become passionate, and shut down speech that in any way seems to give comfort to the other side. That’s a huge one. The nastiness of our culture war. And related to that, the 2016 election and the inauguration of Trump. Right around then is when we see most of the actual violence. There hasn’t been a lot of violence on campus, but what there was especially happened right after the inauguration.

Another intersecting thread is the huge rise in depression and anxiety that began around 2012. Students who were born after 1995 are not millennials—they are Gen Z. Gen Z has much higher rates of anxiety and depression. And when you bring that cognitive style onto campus—there’s research we talk about in the book—there’s research showing that depressed and anxious people are more prone to put the worst possible reading on things. If there’s ambiguity, they’ll see the most threatening, negative version possible and it’s very difficult to change their minds about it. So that makes it very hard to have a seminar class. It makes it very hard to have a discussion about complex topics. So rise in mental illness.

Third is paranoid parenting. We started telling kids in the 1990s, and especially after 9/11 and Columbine: The world is dangerous. If you’re outside, you’ll be kidnapped. Now, this was never true. The world’s getting safer and safer. I grew up in the ’70s during a gigantic crime wave. Just as the crime wave was ending in the 1990s, we freaked out and thought the world too dangerous to let kids out.

Related to that then, the fourth thread, is that in addition to telling the world is scary, we said “you don’t get to play anymore. You don’t get unsupervised playtime.” Lots of soccer practice, lots of organized activities after school. But we’re never gonna give you the chance to just be outside on your own, exploring the woods, going to town, buying a candy bar with your friends. Not until you’re 14, or 12, something like that. So we took the most important experiences of childhood away from kids in the 1990s. That’s the fourth one.

Fifth one is bureaucratic changes driven in part by fear of liability that led university administrators to crack down on speech more and to implement reforms that put us all on eggshells. So, for example, in every bathroom at NYU, there are signs telling students how to report me anonymously if I say something that they find offensive. That means I can’t take chances, I can’t tell jokes, I can’t trust them, even though most of them are great. But if one student in the class takes offense to one thing I say it could mire me in weeks and weeks of bureaucratic difficulty. So I don’t take chances.

And then, the last one is new ideas about social justice. Everybody agrees that people should have equal opportunity. That, there’s widespread agreement about. But when some groups are now arguing that nothing is fair until it’s exactly proportional, 50 percent female, 15 percent African American, that might be a desirable endpoint, but if you treat every institution as corrupt and evil until it achieves that, you’re misunderstanding institutions and you’re committing yourself to kinds of activism that will never be successful. If you won’t look at the pipeline, if you won’t look at the preconditions, you cannot understand how an institution works. So you put those all together and I think we have the package of almost like fuses that sort of all came together and came to a single point around 2014, 2015.

What’s a lecture topic that you feel you need to be guarded in explaining?

Anything about gender differences. I teach a course on professional responsibility. I teach a course on work, wisdom, and happiness. And in both classes, here I am in a business school, men and women are basically equal in abilities. There are very few areas where men are superior or women are superior—there are a couple where there’s small differences—but the huge difference between men and women is what they choose, what they enjoy. And you see this in the play preferences of boys and girls. Now, I can say this to you on camera because you’re not my student. You can’t report me. If somebody sees this video they can’t arrest me for saying this.

But I wouldn’t want to talk about this in class. I always did, up until a few years ago. If we’re trying to say, “What makes people happy in work?” And, there are differences in ambition. There are differences in workaholism. Men are motivated to socially display, to display success and wealth, and so they tend to have their … there’s research that shows they’re higher in achievement motives. Women, on average, are higher on relatedness motives. This is very relevant to understanding why men choose certain careers and women choose others.

But if I talk about this in class and someone says, “Are you saying that the cause of these differences is not sexism? Are you denying my experience?” Someone could be offended by that; and from the time of Socrates, until about 2014, it was okay to be provocative as a professor, and if a student got upset by it, well, that upset could be productive and you could work through, like, “What’s going on here? Why do you think it is?” You could have a debate or discussion. But I wouldn’t try that now.

What advice do you have for new fathers like myself?

So my book, The Coddling of the American Mind with Greg Lukianoff, it began as a book about what’s going on on campus—but it quickly became a book on child rearing and parenting. Originally, when we wrote our Atlantic article in 2015, Greg and I thought that the problems—the fragility, the claims about emotional safety—we thought those originated on some college campuses. But we very quickly learned: no, the problems are baked in by the time students get to college. What we didn’t understand back then is that the social world for kids born in 1995 and later is really different from the world of kids born before then.

Before the 1990s, kids had a lot of independence. They went out to play. They had time unsupervised. That’s crucial for child development. Kids are anti-fragile, they need to fall down, they need to get in fights, they need to get lost and find their way back. In doing so, in facing risk and facing challenges, we get stronger, stronger, stronger, stronger until we’re ready to go off to college and live independently. But in the 1990s, we decided: no more of that, the world’s too dangerous, no more practice being independent until you go off to college—and then you’re not independent. The cost has been devastating. The rates of anxiety and depression are skyrocketing, especially for girls. And so I think the most important lessons that we can take for child rearing now are that we have grossly overdone the protection and the academic pressures in elementary school.

Kids need to play. They need to play without supervision. They need to play. I’m not talking about 2-year-olds. Two-year-olds you can supervise; they can really hurt themselves. But by the time they’re 5 or 6, they need some time unsupervised. And we keep taking that away from them thinking it’s more important that they learn to read, that they do math. So the most important advice that we can give to parents is: Back off. Let your kid play. Let your kid grow. Don’t over parent.

Now, you can’t just decide this on your own because you and your kids are strongly influenced by what others are doing in your neighborhood and then what happens at school. So be very careful, especially if you send your kids to private school. A lot of private schools are … they’re very variable. Some, I think, like Waldorf or Montessori, do give more independence; but a lot of them are very over-protective and then when they get older they teach some really awful ideologies that I think are very political and are not good for kids.

So be very careful if you choose a private school. And basically remember that your kids are antifragile, not fragile. They have to have some setbacks, some failure, some suffering even, at some point. You can’t protect them from everything and if you do, you’re harming them. I urge all parents to go to letgrow.org. It’s a wonderful organization started by Lenore Skenazy, the woman who wrote Free-Range Kids, and it’s full of advice for how you can create conditions in which your kid will actually grow and become an independent, functioning human being.

Brian: Your young daughter recently walked home by herself. How did that make you feel?

So recently, my daughter, who’s 9, walked to school all by herself, in New York City. Now, when my parents grew up in New York City, they took the subway to school. They did all sorts of things at the age of 7, 8, 9. But today, if you let a 9-year-old out, you can be arrested in some parts of the country because, “Oh my God, what a terrible parent. What if she’s abducted?”

My daughter is very independent-minded. She actually has read Lenore Skenazy’s book, Free Range Kids. It’s a very easy book to read; we read it together actually. And she’s very proud of the fact that she’s allowed to go out and play in Washington Square Park all by herself—and we’ve been doing that since she was 8. She’s wanted to go to school all by herself, and because Seventh Avenue near us is big and complicated, I said, “Not yet; not yet.”

She can cross Sixth Avenue, which is easy. She can go to the pet store and buy worms for her gecko. So she loves being independent. And finally, after we practiced crossing Seventh Avenue (it’s complicated) … we practiced crossing it a lot of times and I sent her out on other errands, like getting bagels in the morning. I felt she was ready. And so yeah, last week for the first time in her life, she walked by herself to school. Now she’s not allowed to walk home. That’s illegal. The school would never let a child walk home, but they can’t stop us from letting her walk to school by herself. And she loved it.

You’ve written that Republicans understand moral psychology better than Democrats. Do you think that’s still true in the age of Donald Trump?

So, my own research is on the psychological foundations of morality, and my original research in this area was a theory that my colleagues and I called moral foundations theory, where we showed that there are at least six taste buds of the moral sense: Care, fairness, loyalty, liberty, authority, and sanctity or purity.

We also showed that people who call themselves progressive or on the left sort of put all their eggs in one—not one basket—but they especially build on concerns about care for victims and fairness as a quality, and then sometimes also liberty. And they tend to reject moral appeals based on group loyalty or authority or a sense of sanctity or purity; not always; they can use sanctity, purity for environmental concerns.

So in the 1990s and then in the 2000s, it was generally the case that the left/right spectrum in America had social conservatives on the right leading the Republican Party, and progressives on the left leading the Democratic Party. During that time, I published research, led by Jesse Graham, who’s now at the University of Utah, showing that if you ask … At our research site, YourMorals.org, in one study we assigned people to fill out the Moral Foundations Questionnaire—our main survey—fill it out as yourself or for one-third, fill it out as if you were a conservative, or as one-third, fill it out as if you were a progressive or liberal.

What we found—because we actually knew how do progressive and conservatives fill it out—what we were able to show is that conservatives can pretend to be progressives and they can accurately fill it out as though they were one. But progressives can’t pretend to be a conservative and fill it out accurately because they don’t really get the group loyalty, respect for authority, and sanctity or purity. They don’t really get those so they kind of dismiss those and they assume that conservatives just like to kill puppies and things like that.

That was the case for a number of decades. Trump has shifted a lot of things around. The Republican Party is no longer the social conservative party. I believe, in other research I’ve published with Karen Stenner, a political scientist in Australia, Trump is appealing to more authoritarian tendencies. It’s very hard to see how Donald Trump is a conservative. So the psychology that I just described a moment ago no longer quite applies. The Republican Party, I don’t know what’s happening to it, but it is bringing in elements that are overtly racist. It is bringing in desires for rapid change, which is not a conservative virtue, generally.

So I think we’re in a time of chaos in which both parties are in flux. What might come out is we might get ever further away from having a center-left Democratic Party and a center-right Republican Party, which is what we had for a number of decades. We might have two much more polarized or ideologically disparate parties and it could make for some very interesting politics and even less cooperation than we have now.

Brian: Do you think that the emphasis on sanctity has moved to the left more?

Yeah, let’s talk about that. So, of all the moral foundations, the most confusing and, I think, the most interesting, is the sanctity foundation. This is the idea that human beings are able to make something sacred. That means it has value beyond its material properties.

So, you can see this most clearly in a flag. The American flag is a piece of cloth, and if you think it’s a piece of cloth and you want to use it for self-expression purposes, you should be able to burn it. The First Amendment guarantees you the right to political expression. But if you think that flags have almost magical properties and it’s vital that the flag not touch the ground, that would sully it. That would desecrate it. And it’s the same thing for books. If you treat the Bible as the physical object of the Bible must be protected—that shows that your mind is able to invest sanctity or sacredness or purity in something and you want to keep it safe from contamination.

This is used, especially on the political right, for social conservatives for God and country. But we’ve all seen it on the left too. If you go into natural food stores, if you go into any community that does yoga, they’ll talk a lot that sort of the far left will have, or the cultural left—they’ll have a lot of ideas about toxins and purity that they tend to use about the body, and then also about the environment.

Now, obviously, there are real toxins in the environment. I mean, I’m an environmentalist. It’s the left which pushes to protect the environment. That’s all good. But you can see this, for example, in nuclear power. If you really care about global warming, you’ve got to support nuclear power, at least for a while. We’ve got to get off coal. There’s no two ways about this. No renewables are going to replace coal in the next couple of decades. We have to have nuclear.

But if you treat nuclear as this as a desecration of the Earth, as though it’s contagious, under no circumstances would you allow nuclear, you’re showing sanctity thinking, and that is a kind of a religious mindset. You’re committed religiously to certain propositions and you might react very strongly, especially to a member of your in-group who says, “You know what? Maybe we should try nuclear.” Like, “Whoa. You’re out of here.” So, blasphemy. If people are showing signs of blasphemy laws, of punishing non-orthodox thinking, that’s how you know you’re in the realm of sanctity and purity.

How do you understand your role as a public intellectual?

So, I’m a social scientist. I am a social psychologist but I love all the social sciences, and I think to understand any complicated social problem, you need sociology, and psychology, and political science, and economics. So I love the social sciences. And I see my role as someone who has spent his life studying morality from every possible angle. Historical, evolutionary, cultural, anthropological.

We have a lot of problems in our society brought on by the hyper-activation of our ancient tribal moral psychology. We evolved for life in small-scale societies that were frequently at war or in violent skirmishes with nearby groups. Somehow, we managed to grow into gigantic prosperous societies that are generally peaceful. The trend on that has been amazingly wonderful as Steven Pinker has shown in his books. But I think the arrival of social media, in particular, has reactivated a lot of our mob-based or tribal sentiments in ways that make democracy more difficult.

I see my role as someone who’s not on either team—I’m not on the left, I’m not on the right. In terms of voting I’m on one side. I’m not a fan of the Republican Party, but I’m not a member of either team. And for that reason, I think a lot of people feel that they can invite me to conferences or to comment on things and I’m not just there to score partisan points. My view is that all social scientists should be committed to understanding society much more so than fighting for one side.

Why do you identify as a centrist?

So I consider myself to be a centrist because I take very seriously the psychology that I reviewed in my book, The Righteous Mind—most of it not my own work but the work of others—showing that we are all designed by evolution to confirm what we want to believe. We’re very, very good at confirming hypotheses. We’re not very good at challenging them—our own hypotheses; we’re really good at challenging other people’s hypotheses. And what this means is that if you put me together with a bunch of people who think just like me, we can’t possibly find the truth about anything complicated because we’re just going to confirm each other’s share. We’re going to confirm the values, the hypotheses, the explanatory forces that are our favorite mechanisms to talk about.

I began writing The Righteous Mind in order to help the Democrats win. That was my goal in 2004 when I began this line of research. But once I actually started reading the best conservative writing, going back to Edmund Burke and Michael Oakeshott in the 20th century, and Thomas Sowell more recently—once I began reading conservatives and then libertarians, I realized, “wow, you actually need to expose yourself to critics, to people who start from a different position.” You can’t find the truth about complex or wicked problems unless you have a community that includes guaranteed dissent. So I consider myself a centrist because I am committed to the idea that you have to be listening to both sides. It doesn’t mean that the answer is always in the middle. It’s not. Sometimes the left is correct, sometimes the right is correct. But if you start from an a priori position that our side is right, their side is evil and I’m not going to listen to their arguments, you’re guaranteed to get it wrong.

What is the rationalist delusion?

In The Righteous Mind I wrote about something called the rationalist delusion. And that is the belief that people can be perfectly rational, and if only they would be perfectly rational then those rational people would find the truth. And this grew out of, if your viewers remember, the New Atheists.

There was a period … I think after 9/11, a lot of people began thinking about the power of religion to lead to mass murder. And a bunch of books came out in rapid succession by Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Dennett. Also Christopher Hitchens. So they were called the Four Horsemen of the New Atheist movement. And most of them tended to speak as though if only we could be rational like scientists, not stupid like religious people. And I’m an atheist. I’m a Jewish atheist. I have no particular love for religion. But given that I was studying how we’re all driven by our emotions and motives, and we have these intuitions and we seek to justify them, I thought scientists aren’t necessarily better than anyone else as individuals.

We’re not more rational as individuals. We’re more rational because this social institution that began developing in Europe in the 17th century, a community of people who would read scientific treatises and letters and then critique each other—that’s what science is. It’s institutionalized critique. It’s guaranteed dissent. That makes people smarter. And so I love science. I think science is a better guide to reality than religion, certainly material reality. But I thought that the New Atheists had it wrong, and so I saw signs in some of them of quasi-religiosity—that is, worshiping reason. Now, reason is great but if you worship it, that means you’re blind to evidence, that it’s not perfect. And it’s not perfect. In fact, it’s very, very flawed. It’s very, very social. So I think that people can be rational but only if you put them in groups that make them rational despite their flaws.

Brian: I think Johns Hopkins Philosophy Department received a $75 million donation recently. Are you skeptical of the idea that we can teach students to be more responsive to reasons and reasoned argument?

I was thrilled that Johns Hopkins received that gigantic donation to create, I think they call it the Agora Institute. And I’ve spoken with the president of Hopkins about this. I’m actually very optimistic. I think, from what I know, they’re going about this in an intelligent way. As long as they can teach about humility; teach students how the mind actually works; teach them the problems of democracy, the reasons why our founding fathers were so worried—because they read the ancient Greeks and the Romans. They saw what happens in all kinds of political systems. So I think as long as they don’t make it seem as though, “oh, you’re here to study reason”; no, you’re here to study society, I’m optimistic about this. They know that Western liberal democracies are facing potentially existential threats. And they’re just beginning, but I think they’re off to a good start.

Do you think that morality is a matter of taste?

So what is morality? There are two easy positions. One is moral truths are just like other kinds of truths. So Earth is the third planet from the sun; gold is a better conductor of electricity than is aluminum. Those are facts, man. That’s physics and chemistry and astronomy. And it was true before humans existed. And if extraterrestrials were to come to our solar system, they would find out that those two things are true.

Similarly, everyone should have equal rights. Men and women should all have the same roles and opportunities, and we should not divide anything by gender. It should be everything. These are facts, man. They were always true and they’d be true even if extraterrestrials came here and they had different genetics and different social structure. They would agree with us if they were sufficiently rational. That’s one idea, moral realism. And that’s an idea that Sam Harris put forward in his book, The Moral Landscape. It’s one that I disagree with.

The alternative view is, “hey, there’s no moral facts, there’s no moral treatise. You like vanilla, I like chocolate. Neither one’s right. You like mass murder, I don’t. Neither one’s right. It’s just a taste, man.” And I’m sort of paraphrasing Isaiah Berlin there. He said something to that effect. So there’s either moral realism or there’s moral subjectivism. It’s just my taste, my preference. I don’t think moral truths fit in either of those categories.

I call myself an emergentist. That means moral truths emerge from certain kinds of interaction just like prices in a marketplace. So right now I believe platinum has a higher price than gold, which has a higher price than silver. That’s a fact, man. But it wouldn’t be a fact if extraterrestrials came here and there were not people, there was just platinum and gold and silver in the ground. It has no intrinsic value. As we trade in marketplaces, the prices emerge. Similarly, as we interact with each other over time, rights emerge. Now, they don’t emerge early in our development—only once we develop a certain degree of material prosperity, freedom from the demands of survival in daily life, then rights begin to emerge and they become facts. It is now a fact that every career, with maybe just a few exceptions, every career should be equally open to men and women. That’s a fact now. But I am hesitant to say that 100,000 years ago, proto-humans were wrong to divide hunting and gathering. That was just wrong for them to be specialized by gender. So I think moral truths exist but they exist as emergent facts about interaction, not as truths of physics.

How have philosophers responded to your views on moral reasoning and moral facts?

I’ve engaged with philosophers a lot. I spent a wonderful year at Princeton in the Center for Human Values, which is mostly a group of philosophers that are interested in social science questions. And we spent a lot of the time kind of miscommunicating and misunderstanding each other over the question of whether empirical research in psychology, or neuroscience, what implications does that have for normative ethics, for claims about what is right, what we should do?

I was a philosophy major myself. That’s how I got started on this. I wrote my senior essay as an undergraduate on free will and determinism. The question: If determinism is true, if the movement of every atom and electron and every neuron is determined by the state of the universe just before, does that mean that we’re predetermined to act in certain ways? And if so, how can you blame anyone? How can free will be compatible with causal determinism, or how can moral responsibility be compatible with causal determinism?

So I’ve always been interested in philosophical questions. And I think a lot of philosophers have read my work now and have engaged with it, and many of them are critical. Some of them embrace it. So I think there’s a very healthy discussion between philosophy and psychology. It especially grew as Stephen Stich at Rutgers was one of the people right around the time I began writing in the 1990s, who really was bringing together philosophers and psychologists. So we have a healthy relationship, which I think is mutually beneficial.

What is Heterodox Academy and why did you start it?

I co-founded an organization called Heterodox Academy in 2015 because I began to notice that the quality of discussions among faculty in the social sciences was suffering because we didn’t have enough viewpoint diversity. In 2011 I was invited to give a talk on the future of social psychology at the big annual convention of social psychologists, and I gave my talk on the bright post-partisan future. I imagined some day, we’ll realize that we need dissent, we need argument and we will actually try to recruit more conservatives—because almost everybody is on the left. I was only able to find one person in my whole field who wasn’t on the left.

And so I gave this talk in 2011. It was actually very well received. My field is everyone’s on the left just about, but they’re not ideologues. They’re scientists first. So I made my arguments carefully and people generally said, “Oh, that’s a good argument. Yeah, you may be right about that.” But then as time went on and as the culture war heated up, and as left and right hated each more and more, I started noticing that really important public policy questions about immigration, inequality, gender, race—I’d be in a room with other social scientists and someone would say some hypothesis, and there’s obviously a confound there or there’s some reason to question it, but nobody would say it. Because you don’t want to be seen to be questioning the narrative about pervasive racism, sexism, homophobia, et cetera.

And if you can’t question a hypothesis, then it’s not science. So a few of us in psychology wrote a paper explaining how the loss of viewpoint diversity, it will reduce the quality of our research. That was published in 2015. I happened to have lunch with Nick Rosenkranz, a professor in law at Georgetown Law School, and he had just written a paper that showed the same problem in law. Law professors are almost all on the left. Yet lawyers are trained and they have to go out and argue cases before judges, half of whom were appointed by Republicans. And so we’re not training our students well if they’ve never encountered a conservative legal mind.

And so Nick and I thought, “wow, this could be a problem all over.” A sociology grad student named Chris Martin happened to send me a paper. Same problem in sociology. Everyone’s on the left and that means we don’t ask certain questions, we can’t find certain answers. So the three of us thought, wow, we should get together and put up a website and put our papers up there and see what else is out there. So that became Heterodox Academy. It was entirely a faculty affair about the quality of social science work in September of 2015.

A couple of months later was the Halloween protests at Yale University which then went national, and we had a couple of years of a lot of protest and changing political norms. And so I believe that the climate for speech on campus is worse now than it was a few years ago. So Heterodox Academy is still mostly focused on research, but it’s also now working to improve the campus speech climate.

It’s not about free speech, like you can say whatever you want; it’s about free inquiry and being able to speak up in class. Can you engage in a dialogue in a classroom? A lot of students all over the country tell us, “No, we feel like we’re walking on eggshells. We self-censor.” The organization is now run by Debra Mashek who is a professor at Harvey Mudd College in California, and as one of her students put it, “My motto is silence is safer.” That’s the way to get through college. Just don’t say anything. You won’t get in trouble. That’s a terrible attitude to have in college, but it’s one that many students are beginning to adopt.

What did you make of the recent hoax on academic journals that ostensibly focus on “grievance studies?”

I really enjoyed the grievance studies hoax because we’ve all kind of lived with … In the academy, most of us feel that our purpose is truth. What we worship is truth. I think each institution has to be clear about its telos and ours is truth. We must never sacrifice truth and we hold each other to account. If a professor says, “All of X are Y,” someone said, “Wait a sec, you don’t mean all; you mean almost all.” We’re really supposed to not say things that are not true.

But there are certain departments in which it’s clear that the rhetoric is not this sort of careful academic, “is it true?” It’s “we’re in a fight against evil and are you on our side?” We’ve all kind of lived with that for a long time, the gender studies department, various race studies departments, the education school, social work, parts of anthropology, parts of sociology. Those are the areas that are more activist.

I don’t want to paint with too broad a brush. There’s some great scholars in each of those departments, especially in anthro and sociology—I love those fields. But it’s long been clear that as long as you show that you hate the right people or groups or forces, you’re going to be sort of … The standard for publications is very low. That was the point of the Sokal hoax long ago. Alan Sokal showed that as long as he said, “Oh, everything’s a social construction.” They waved him in even though nobody could understand his garbage paper. So in the grievance studies hoax, it was on a much bigger scale. They had a lot of fun with it. I mean, they paraphrased a section of Mein Kampf and submitted that for publication with just changes to who the bad guys were. So it was delicious. It was delightful.

I think it really was showing up whole areas of the academy that are in massive violation of our telos. They are activists, not first and foremost scholars. The culture in those departments is one of ideology and orthodoxy, not of openness to the truth and educating minds to be better at perceiving truth. So I think it’s important that they were humiliated, as it were. I should point out in sociology, none of the articles were accepted. Sociology is a real academic field. But a lot of the studies departments I think are not necessarily real academic fields.

What is your view of the so-called intellectual dark web?

The intellectual dark web is a label put on a bunch of people who are intellectuals—some are professors or former professors. As far as I can tell, it mostly just refers to people, most of whom are on the left or consider themselves to be on the left, who are critical of certain trends of the intellectual left.

So, there’s a webpage that lists me as a member, and Steve Pinker, Nicholas Christakis. There’s nothing dark about us. We are tenured professors. We can publish in The New York Times. So as a label, the dark part is kind of ridiculous. That doesn’t really apply. But to the extent, if there is a kind of a political orthodoxy in many parts of the university, there is also this new media ecosystem based around podcasts, which is much more free flowing and where people can say things that they wouldn’t say in the classroom.

I’ll talk to the people in the right or the left—I won’t talk to anybody in the world. I mean, there are certainly groups I wouldn’t talk to—but I’ve spoken with … I was just on Joe Rogan. I’ve done, Rubin, Jordan Peterson. So there are a bunch of people who have discussions that reach millions of people. So there is something there. There is taking advantage of the new technology. There is a rich intellectual life that’s not at the university, which I think is really interesting, especially because what really is amazing to me now is for decades we’re all supposed to say, “Oh, people’s attention spans, oh, the kids today.” Now, it’s a tweet, now it’s 120 characters, oh, the attention! But yet there’s this gigantic market for two and three-hour conversations. So I think that’s pretty cool.

You’ve also helped found another organization called Ethical Systems* that tries to get organizations and other sorts of systems to behave more ethically. How do you do that?

So we’re sitting here at the Stern School of Business at New York University. This is where I work now. I happened to come here in 2011 just because I needed a way to pay the real estate costs when my last book came out. I had no training in business or in business ethics and I just wanted to be in New York City for a year when The Righteous Mind came out. So I called up a professor here that I knew, I’d spoken here in their ethics series, and I said, “Bruce, is there any way I could teach ethics for a year here so that I can be here when my book comes out?” He said, “Sure, we’d love to have you.”

So he made a space for me. Got me a nice NYU subsidized rent apartment. I moved up here with my family. Because this was right after the financial crisis, well, this was 2011, so still very much in the wake of the global financial crisis, the Bernie Madoff scandal, lots of scandals in business. A lot of people then were saying, “Those business schools, they’ve got to teach those MBAs ethics. They’ve got to put ethics into their heads,” is the idea. But as I said in The Righteous Mind, no one will ever invent an ethics class that makes students behave ethically after they leave the classroom.

Because I’m a social psychologist, I think we’re influenced more by the forces around us than by our inner core commitments. So I wrote that line and then Stern offered me a job. They said, “Do you want to stay here? You want to join our faculty? Oh, and by the way, you’ll teach the ethics class.” So then I had to design the ethics class that would do this. But what I did was I embraced the social psychology. I said, “We’re not going to teach MBA students, be ethical, be ethical, and then expect them to resist these incredible forces at work on them in real situations.”

Rather, let’s teach them ethical systems design. Let’s use the social psychology and help leaders who want to create ethical organizations, help them to change the social forces, improve the culture. Culture is incredibly powerful. If your culture values cleverness, getting around the rules to show how clever you are, well, you’re basically putting huge amounts of risk, ethical risk, which turns into legal risk, lawsuits, regulatory interventions. But if you, as many executives do, if you want your organization to have an ethical culture in which people trust each other, in which people’s word is their bond, in which you don’t have to constantly monitor people because everyone shares the same mission, well, it turns out that actually is more profitable because trust is more efficient.

So how can you do that? How can you create an ethical culture? So Ethical Systems, I founded it by inviting lots of other professors, researchers who knew about accounting and finance and conflicts of interest, areas that I didn’t know anything about—and together we summarized the research. We make it very easily available to business people all around the world for free. Now, we’re doing a variety of projects to help companies measure their ethical culture and then do simple procedures, simple steps to improve it. We think that business is basically good. Business is about bringing people together to do something, create value for others that they couldn’t create on their own. Business is incredibly powerful and when businesses go off the rails, when industries become predatory, a lot of people suffer; but when they’re honest, when they make a good product, when they treat all their stakeholders well, the benefit to society is immense. So that’s what ethical systems is about.

What would you be if you weren’t a scientist?

Well, historically, what I can say is that when I got out of college I had no idea what to do with my life. I had learned how to be a computer programmer, and I thought of moving to Spain and starting a computer consulting business because I spoke Spanish. I love Europe, I love living in Europe. So I thought of doing that, but I didn’t quite have the guts and it would have been very difficult in terms of regulatory affairs.

I almost went into computer science and computer programming in various ways. I almost applied to grad school in computer science. I think I love the academy. I love being a professor. I might’ve been in a different field … I don’t know. I suppose I might’ve worked in a think tank or a foundation. I’ve always been the sort of person who is much more interested in ideas than in things or people. And that’s sort of the big three: ideas, things, or people. Most of us, if we had to pick one to make our life in, we’d pick one or the other.

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @BSGallagher.