In early June, about 150 miles off the western shore of Costa Rica and 10,000 feet below the ocean’s surface, an octopus hatched just in time to see an alien invasion. As the newborn slipped from her egg and into her world—a strip of rocky seamount heated slightly by hydrothermal vents—a remotely operated submersible, the ROV SuBastian, was getting to know the place too, turning LEDs and cameras on the otherwise lightless enclave.

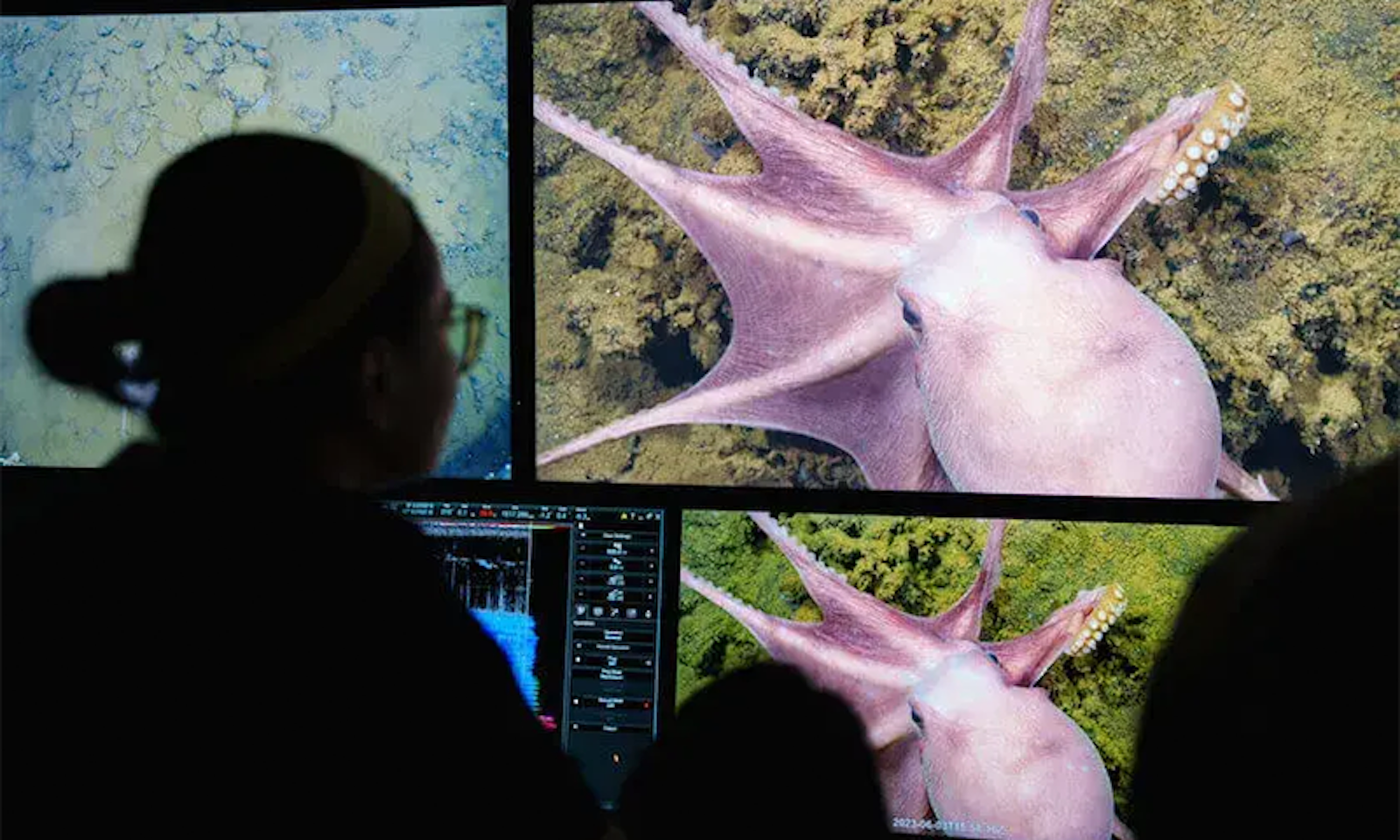

Several feet from the SuBastian’s chunky robotic arm, the octopus flexed her own spaghetti-thin appendages for the first time, propelling herself out from under her mother. Two miles up, watching the video feed from the control room of the research cruiser Falkor (too), marine biologist Diva Amon saw it happen. “Oh, whoa,” she said. “Is that a baby?”

Each one was like the pink squiggle of a proofreader’s correction.

As more hatchlings scooted across the screen, the dozens of scientists and crew members on board—all members of the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s “Octopus Odyssey” expedition—became exuberant. “There was squealing and excitement and pointing,” recalls Beth Orcutt, a geomicrobiologistat the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences and one of the expedition’s chief scientists. “It was a riot,” says Jorge Cortés-Núñez, the other chief scientist and a coral reef specialist at the University of Costa Rica. “It was spectacular.”

Benthic enthusiasts around the world joined by livestream in welcoming those deep-sea babies, whose species is still unknown. For the researchers on board, the hatchlings’ presence was the beginning of something more—a many-armed unfurling of questions, goals, and possibilities.

Before the expedition, the name “Octopus Odyssey” was optimistic. Ten years ago, researchers took a submarine down to this area, known as the Dorado Outcrop, and came upon dozens of brooding female octopuses, the first such grouping ever found. (Most octopuses tend to their eggs solo, to minimize interference during a long and arduous process. Octopus mothers also die after brooding.)

But that discovery was tinged with sadness: The eggs lacked the usual signs of life, like visible eyes. “I’m thinking these are losers … they’re doomed,” remembers Janet Voight, a cephalopod expert at the Field Museum, of watching videos from that first trip. She and two colleagues published a paper that called the population “an ill-fated fragment,” positing that the warm, low-oxygen fluid percolating through the outcrop killed any eggs that were laid there.

For the month before Voight left on this most recent cruise, “the big thought in my brain was, ‘What if there’s no octopuses now?’” she says. When SuBastian crested the outcrop to reveal one brooding mother, then a cluster, followed by the parade of hatchlings—each one like the pink squiggle of a proofreader’s correction—she was ebullient. “Being wrong about that population was a great relief to me,” she says. “It took me all day to calm down.”

Seeing scores of mothers gathered and hatching babies also cracked open new questions about what made this site hospitable after all. Was it the warm water (which can speed up egg development) or clean substrate (which allows octopus moms to more easily glue down their eggs)? Were beneficial microbes being pumped through the hydrothermal vents? After “the emotional response” came “the science response,” says Voight, who quickly began counting individuals and noting where eggs were positioned.

On this latest expedition, the team also planted artificial shelters—tempting, sediment-free places to lay eggs—within and outside of the warm fluid flow, Voight says. When the researchers return, they’ll see which shelters the octopuses have chosen, giving insight into whether the fluid itself influences their choice of brood sites.

Beatriz Naranjo Elizondo, a marine biologist and imaging specialist at the University of Costa Rica, watched SuBastian traverse the nursery live from the Falkor (too)’s control room, standing with a group of other early-career researchers from Costa Rica. As the baby octopuses revealed themselves, “we were hugging and everything, clapping,” she says. “It was like being in a stadium, giving support to your team.”

“Oh, whoa,” she said. “Is that a baby?”

Ninety-two percent of Costa Rica’s territory is offshore, and more than a third of that is more than 1.5 miles deep. In the middle of national conversations about trawling and oil exploration—and international conversations about deep-sea mining—the Octopus Odyssey team’s Costa Rican contingent was eager to catalog what they found in their country’s hydrothermal vents, seamounts, and abyssal plains, Elizondo says. In addition to the baby octopuses, the team saw ancient corals, siphonophores, a skate nursery, and many other wonders.

“No one knows anything about the deep sea, and Costa Rica is basically deep sea,” says Elizondo. “Each one of these places has a unique biodiversity.” She came away from the expedition with hundreds of hours of video, which she is now analyzing in order to help give the country, and the world, a better idea of who exactly lives there.

Later in the expedition, the team piloted SuBastian to a different outcrop, says Rachel Lauer, a University of Calgary geophysicist. Lauer studies how heat flows under the sea floor, crunching the math and making the models to understand what she calls “the plumbing” of hydrothermal vents and other such systems.

Chasing the implications of heat flow patterns to find where warm water is being pumped out of oceanic crusts had led to the initial discovery of the Dorado Outcrop nursery, 10 years earlier. Now Lauer thought she might have found a similar pattern, suggesting the presence of another low-temperature hydrothermal vent—and, maybe, more octopuses.

Sure enough, the ROV arrived at the predicted point and illuminated a second, smaller octopus nursery, with yet more babies. “I was freaking out,” says Lauer. She eventually excused herself to the ship’s deck to yell.

Heat flow studies are often used for oil and gas exploration, and Lauer’s work can sometimes feel abstract and utilitarian, she says. Encountering the living consequences of the systems she studies—the creatures who have evolved to thrive in variable heat and high pressure—was “like an explosion for my brain.”

In the months since, this excitement has deepened into a renewed commitment to those creatures. Realizing that her expertise “could actually be applied to something as charismatic as an octopus is motivational to me,” she says. “This is the kind of science I want to be doing.” She and others from the cruise are already planning future trips elsewhere, she says.

For Orcutt, the discovery of the nursery’s viability underscored a lesson that applies to all deep sea environments: “You can’t assume that you know it just from visiting it once,” she says.

In December the Falkor (too) and much of its team will return to the Dorado Outcrop. They’ll check the artificial shelters, hoping to determine why octopuses flock to these particular spots. They’ll recover other things they left behind, including temperature sensors and experiments designed to assess what types of microbes grow there. (Microbes play a plant-like role in the deep sea, gathering chemicals from vented liquid and transforming them into nutrients that larger organisms can use.) And they’ll revisit sites that piqued their interest last time.

In the meantime, Voight will work to determine the species of the octopuses they found at the nursery. Cortes and his students will begin publishing papers on observations they made and species they found, and continue pushing to protect the sites where they live.

And the baby octopuses will continue to swim through the minds of the aliens who crashed their birthday party. It’s a big job for a small creature, but it’s the work of life. ![]()

Lead photo courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute.