Imagine walking miles and miles across dangerous terrain frequented by sabertoothed cats just to find the right rock. Around 2.6 million years ago, a group of early hominins in East Africa started to do just that. They decided they needed better tools with which to prepare meals, so they began trekking long distances across grassy open woodland to get the raw materials: rocks that were durable but brittle, mostly quartzite, rhyolite, quartz, chert, and granite. Then they lugged their heavy quarry back across that same formidable landscape for shaping at home.

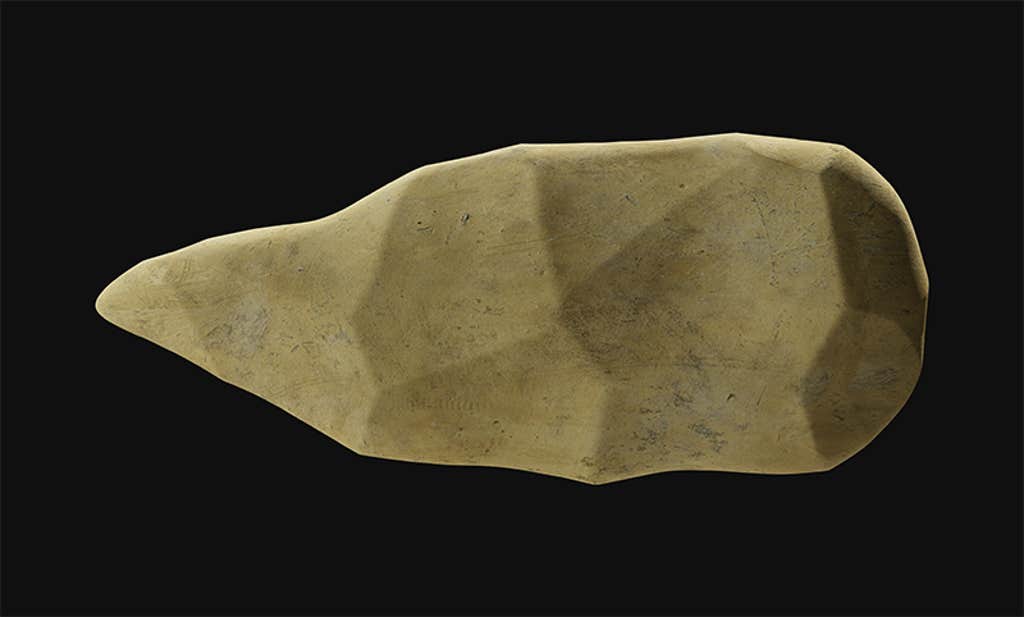

These hominins lived in Nyayanga, a valley in western Kenya that sits on the banks of Lake Victoria and in the shadow of Homa Mountain, and the tools they crafted are known to archaeologists as Oldowan tools, some of the earliest standardized stone tools on Earth. Scientists believe these Oldowan tools were used for things like cutting, scraping, and pounding to prepare plants and butcher hippo meat. But they weren’t certain where the hominins who used them got their materials.

This is really early in the archaeological record.

Now, a team of researchers has revealed that the hominins in Nyayanga were the first to forage for high-quality stones over long distances. In some cases, these treks extended more than 8 miles, farther than many modern people walk in a week, which suggests a high level of planning and forethought. Such are the findings of a recent study published in Science Advances, which puts the timing of such sophisticated tool-making behavior some 600,000 years earlier than most scientists had previously thought.

“This is really early in the archaeological record to have tool makers traveling those distances for raw material sources,” says study author Emma Finestone, an associate curator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The ability to plan out resource use in this way was likely critical to the rise of large-scale food sharing among hominins, according to Finestone and her colleagues.

In the early days of human evolution, the Nyayanga valley possessed a winning combination for settlement: fresh water, food, and shade. But its stones were not great for making sharp and durable tools. The rocks around the valley were soft and dulled easily, says Finestone. When the team of researchers analyzed the geochemistry of 401 different artifacts from the site, as well as how rock traveled through rivers in the valley at the time, it became evident that the residents of Nyayanga were sourcing raw materials from many miles away.

Scientists had previously believed that the first hominins to travel long distances to find stones for tool making did so about 2 million years ago in a region of Kenya known as Kanjera, not far from Nyayanga on the Homa Peninsula. But the new findings suggest that Kanjera’s traveling stone artisans may not have been the first.

Oldowan tools were distinct from the tools that nonhuman primates crafted and used: The hominins who pounded them into shape purposefully removed flakes of the stone core to create a sharp edge, perfect for slicing up hunks of prey for dinner. Nonhuman primates were, and still are, less deliberate about how they shape sticks and stones for tasks.

It is important to note that members of the Homo genus weren’t the only hominins in the Nyayanga area 2.6 million years ago. Paranthropus, a genus of extinct hominin, were also around, which means that the transport of rocks to make sharp tools might not have been exclusive to modern day humans’ most direct ancestors. What it does suggest, however, is that the quest for better tools is even more deeply ingrained in what it means to be human than we thought, says Finestone.

“We forget that we are also animals that are evolving and adapting and surviving,” she says. For millions of years, humans have been striving to perfect the tools and technologies needed to flourish in harsh environments. ![]()

Lead image: Ique Perez / Shutterstock