Lindy Elkins-Tanton, a planetary scientist who studies the evolution of the terrestrial planets and life on Earth, fell in love with science as a girl because considering the vast scales of time and space inherent in studying geology gave her some solace from her personal troubles—it made them seem small and surmountable. A sense of the sublime seems to have permeated Elkins-Tanton’s approach to life ever since. She is always reaching for something bigger, for more meaning, broader questions, more significant projects.

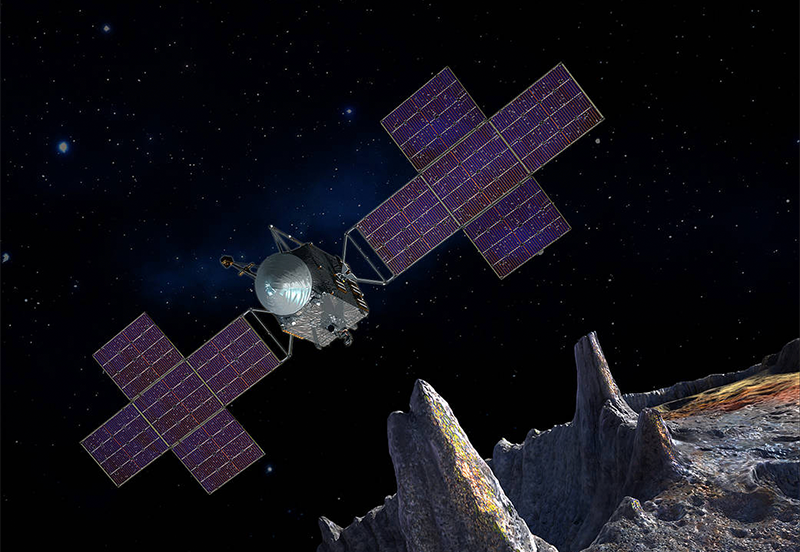

Elkins-Tanton took an unconventional path to her current role as the leader of a NASA mission—for one thing, when she left MIT, she first went into business, a big taboo in academic science. But that early experience in business taught her invaluable lessons about how to manage complex human relationships that have served her well in some of her most far-reaching scientific research endeavors. Currently she is leading a NASA mission to send a spacecraft to investigate Psyche, a metal-rich asteroid orbiting the sun between Mars and Jupiter. The launch is scheduled for late September 2022. It will travel using solar-electric propulsion to arrive at the asteroid in January 2026.

If I have a secret weapon or a tiny human-scale superpower, it is my drive to reject the unendurable.

Elkins-Tanton’s recently published memoir, A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman, covers wide-ranging personal and professional terrain with depth and insight. She recently spoke to Nautilus about the Psyche mission, the events that led to one of the great mass extinctions in Earth’s history, and why she prefers starting lines to finish lines.

In A Portrait of the Scientist As a Young Woman, you explore many intense personal and professional challenges you faced along the way to becoming a successful scientist: childhood sexual abuse, debilitating depression, the loss of your brother, divorce, cancer, and not least, the formidable roadblocks that confront ambitious women in the sciences. What motivated you to write it?

Many people struggle with challenges and a lot of people don’t have a direct shot from high school to their careers. So really I just wanted to connect with people working to overcome the challenges they’ve faced. I would love it if young female scientists were inspired by the book, but I suppose there’s a chance they could also be discouraged, because I talk about challenges in academia and gender issues and implicit bias, as well. My advice for young women, and maybe for anybody, is really to persist. It does seem like continuing to show up and continuing to do your best work and continuing to strive through the challenges that you face is the secret to getting someplace in the end.

What allowed you to persist, when so many people, even within your own family, expressed displeasure at your achievement and leadership, or laughed at your ambitions, or just told you it was wrong for a woman to rise to the top? How did you learn to know your own worth?

I don’t know if I do know my own worth. It seems like it wouldn’t necessarily be a good thing if I had a really high opinion of myself. But I struggled with all of that, with figuring out how to persist, and also realizing that there aren’t that many people who are really thrilled in an unvarnished way for someone else’s success, except for maybe your parents. I had to learn to share less of what was really happening in my professional life with my friends and even family. If I have a secret weapon or a tiny human-scale superpower, it is my drive to reject the unendurable. So it’s not that I overcame the challenges by having more faith in myself. I really overcame them by feeling like I didn’t have another path that I wanted. It was just persistence and stubbornness that kept me going.

You’ve had many successes—research findings, academic appointments, leadership positions, and now the leadership of a NASA mission—and yet you grapple quite a lot in your book with the definition of success in the sciences. Why do you think success is such a fraught concept for humans?

I think it’s almost the drive of a carnivore. You’re after your goal, you’re fighting toward a win, but then once you’ve won, the fight is over and the excitement and the drive and the vision and the direction and the motivation to jump out of bed every morning is done. And then you have to ask yourself, what’s next? Because winning a thing doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s a next step. I’ve seen this happen to a lot of my colleagues in science. They strive for that next big thing, whether it’s tenure, or a particular award in their field, or getting into the National Academy of Sciences. But when it happens, what I’ve witnessed is disappointment. The joy is fleeting, and there are feelings that it should have happened sooner or better. This focus on individual successes and awards just adds up to an academic climate of competition and progress through charisma and fame. I believe it’s so much more rewarding to compete for things that are starting lines instead of finish lines. That’s why I felt so blessed to win this mission to Psyche, because it is just a starting line.

The End Permian Extinction is the closest analog that we have in the geologic record to what’s happening today.

What are you hoping to find on Psyche?

Our leading hypothesis for our NASA mission to the asteroid Psyche is that it is at least part of the metal core of a planetesimal, one of thousands of first-forming tiny worlds composed of metal cores and silicate rock exteriors that crashed into one another to create our rocky planets, leaving behind a few remnants in the asteroid belt. Psyche might be a part of the very first generation of metal cores, and so seeing what it is made of, whether it was magnetized, what kind of rock it came with, will tell us the ingredients that went into our Earth with new fidelity. If the Earth and the other rocky planets are like cakes, then Psyche is maybe the eggs or the flour.

What’s special about Psyche?

The interesting thing about Psyche is that there are really very few objects that appear to be made of metal. And Psyche’s the largest one. It’s an outlier. It’s a low likelihood event in our solar system and it’s probably caused by other low likelihood events. My secret wish is that it would turn out not to be a core part of planet Earth, but something unusual, something surprising, something that would fill in a new part of our ingredients of the planet story. That would be great.

One of your most consequential and hard-won research successes was the work you did to show that specific geological events in Siberia led to the End Permian Extinction 250 million years ago, when 90 percent of the species on the planet died. Why was this so difficult?

Well, hundreds of people were working on this problem of the connection between the Siberian flood basalts and the Permian extinction, not just us, and a lot of them had solved little parts of the puzzle, but no one had really studied these explosive rocks. Their existence almost amounted to a rumor. They were in maps from Russia, but there were no scientific papers about them, except for this one that we found in Russian that was really about pollen contained in the rocks. And so, part of what allowed us to get these quite interesting successes of scientific measurement was that our Russian colleagues managed to figure out where the rocks were and how to get there. And then we had people from all different scientific fields and universities and countries applying their expertise to gathering the data and running it through climate models to ask, could the global effects of these exploding rocks have led to the Permian extinction? And the answer was yes.

What did your findings, which were published in 2015, tell us about our current era, another time of extinction?

The part that was so astonishing to me was that we could show how much sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide was probably released by the exploding rocks, and how acidic the acid rain caused by these explosions was. Together with colleagues from Oslo, we were also able to show that the rocks released naturally occurring chlorofluorocarbons, which had been thought of as just chemicals of our technological age. But the end Permian was a time when, through an amazing coincidence of chemistries and energies, these chemicals were produced in the absence of human industrialization. Today, these gases and compounds removed the ozone layer and caused a huge amount of greenhouse-gas-related warming. Jeffrey Kiehl from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, who was on our project, told me that he thinks that the End Permian is the closest analog that we have in the geologic record to what’s happening today. That’s quite sobering.

You write that it is better to set a goal that can never be accomplished. Then you never plunge into the existential void of success. Do you have an unattainable goal?

Well, with the Psyche mission, the goal by definition has to be very specific and very attainable, down to a very fine level of measurement. But on a broader scale, a goal I have set for myself is to create an educational research system that helps more people feel like they have agency in their lives— like they have an ability to find the source of a problem and make a change. That goal is something that, in a sense, is unattainable because if I do manage to have any influence, it could always be more. So that’s a vision that’ll keep me going forever.

The asteroid Psyche might be a part of the first generation of metal cores. It could tell us the ingredients of Earth.

I was really intrigued by your efforts to teach students at ASU how to design high quality research questions, what you call Natural Next Questions. What is a Natural Next Question?

Here at Arizona State University, we’ve created an undergraduate degree that is built largely around these inquiry classes. In school, we’re taught to receive information that someone else has decided was important and then we have to give it back on an exam, and those are not actually skills that are helpful for later life. In fact, they’re actively unhelpful. What we really need if we want to be great problem solvers, to create change and move human society into the future, is to recognize what questions are not answered, what problems are unsolved, and then have the confidence to take steps toward solving them. And so this is the process that we teach in these classes.

Each week, they go through a research cycle. They proceed as if they were doing a literature review. The first thing they do is think of their Natural Next Question, which is inspired by their natural curiosity and represents one reasonable-sized step toward whatever the big goal is. We have metrics, ways that they can improve their questions and make sure they’re well aimed, specific, and reaching toward that goal. The excellence of their questions can be measured, and over time you can see they improve. And then each student goes off and finds some information that helps them answer that question.

But another thing they learn, which really scares and shocks a lot of students, is that they often can’t find a source that really exactly answers their Natural Next Question. This is shocking because usually a textbook presents a tidy answer to a predetermined question, crafted by the textbook writer or by the teacher. The students get used to finding that everything in the textbook is 100 percent relevant to the questions they have been asked to answer. In real life, that’s not what it’s like. You know, you find a research paper and maybe the fifth paragraph or the second section begins to address what you’re asking, but it’s not quite right. You have to learn to figure out how good your source is and what part is useful.

Thinking about the perfection of the research question, I wondered if you had ever gotten a perfect interview question, one that really struck you and stayed with you over time?

I did recently have a question that surprised me and was very inspiring, which was, “What do you want to do next, after what you’re doing now?” I think it’s clear that my story isn’t over. I’m 56. I’m not finished with my career yet. So that was an exciting question to get, because I keep thinking, how could I be more effective at making positive change in the world, especially around education. It’s so hard to reform education. It’s such a wicked problem. And so I dream about starting our own university or a series of girls’ schools in cultures where girls aren’t usually empowered. ![]()

Kristen French is a Nautilus contributing editor with a special interest in medicine, neuroscience, and the relationship between mind and body. She is based in San Diego, California.

Lead collage by Limbitech / Shutterstock and Sergey Nivens/ Shutterstock