To see additional images from NASA Ames, click the icon on the image at the top of this page.

NASA Ames is filled with the exotic technologies of a future that didn’t quite come to pass. Ancient computers still operate equipment in the machine shop. A decommissioned nuclear missile sits in a parking lot, and the twin of the International Space Station sits out in the open air, under a tarp.

Originally dedicated as the Sunnyvale Naval Air Station in 1933, the site was to serve as a home base for the Navy dirigible, the U.S.S. Macon, which crashed in 1935. The Aeronautical Laboratory was founded in 1939, and in 1958 became a part of the newly formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA. In its earliest days, Ames broke new ground in aerodynamics and high-speed flight. Today it is still an active participant in various NASA missions, including leading the Kepler space telescope mission, and partnering on the Mars Curiosity Rover.

I came to Ames as part of a creatively motivated examination of the felt experience of deep time and deep space, in conjunction with the LACMA Art + Tech Lab. How does one make art—let alone make sense—out of our human experience of the cosmos?

As I visited Ames, along with SpaceX, JPL, and CERN, I began to reconsider our contemporary relationship to space. Without fail, someone would always lament that we have never regained the promise and excitement of the early space era, epitomized by the moon landing. The Ames campus itself embodies that sentiment in its architecture; some structures are perfectly preserved and others are in varying degrees of disrepair.

As I took in the campus, I couldn’t help but think: This used to be the future.

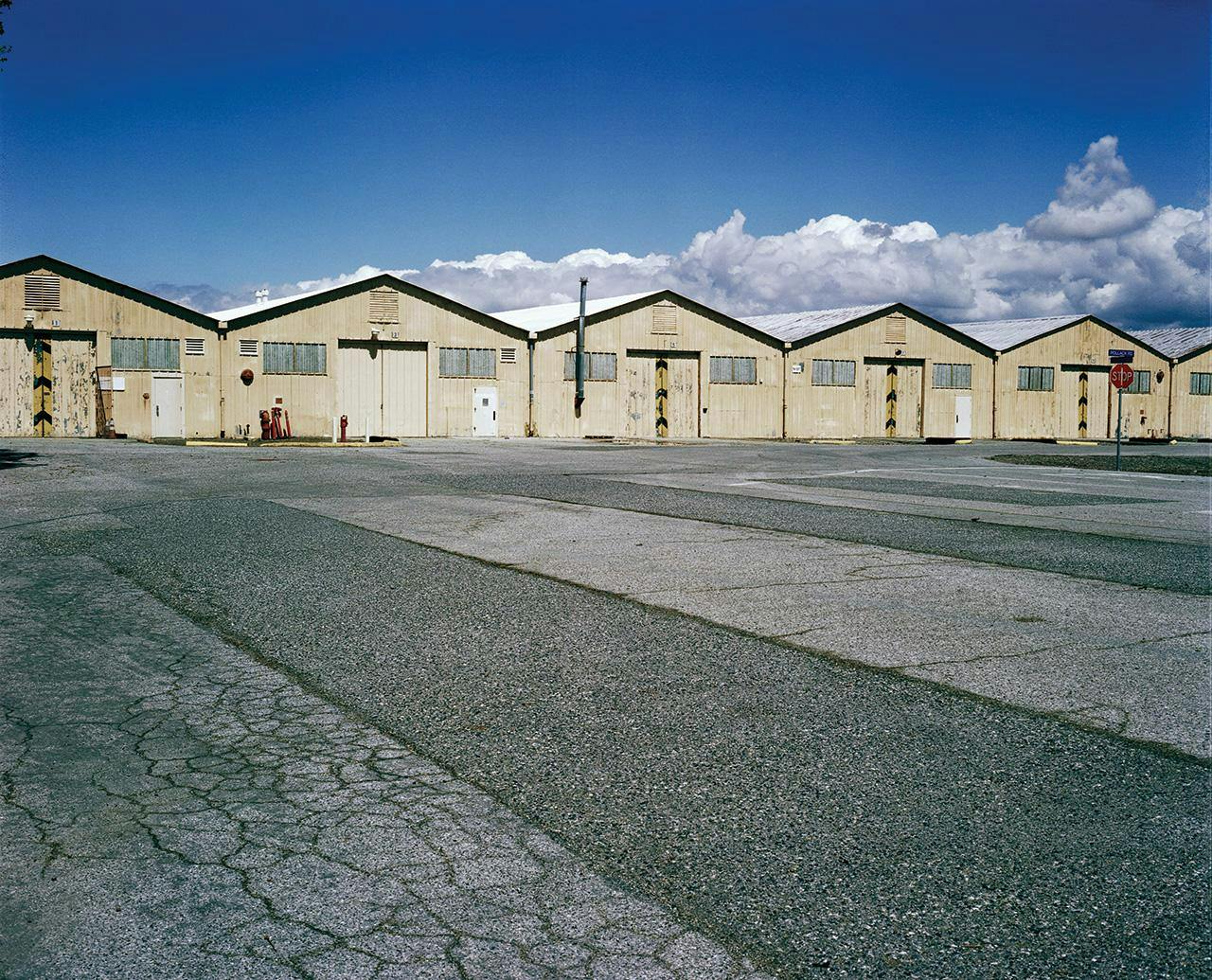

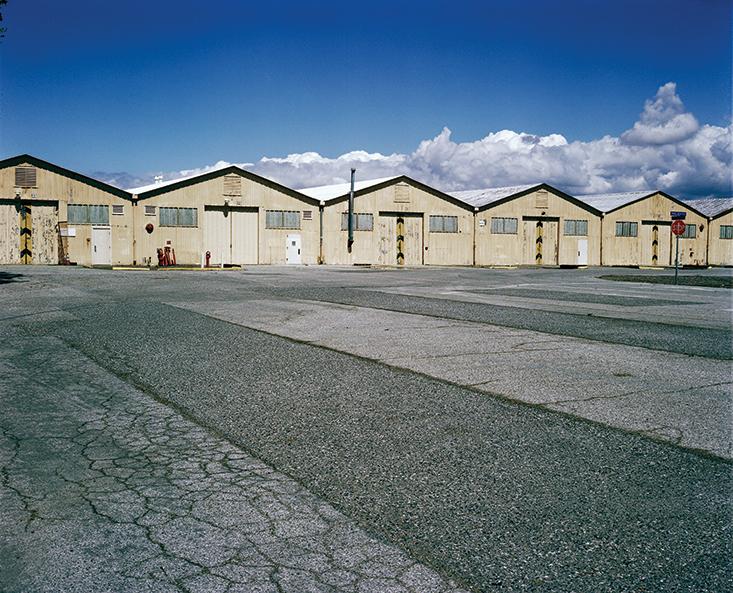

NASA Ames Warehouse N-127 #0415-1301

Pre-fabricated surplus storage sheds, of a type that are common to Naval installations. The sheds contain the detritus from decades of research and experimentation, including machines, electronics and even old vehicles. As one employee put it, “If it’s in the surplus sheds, it’s junk.”

It was unclear what these particular sheds held, or the last time their bay doors had been opened.

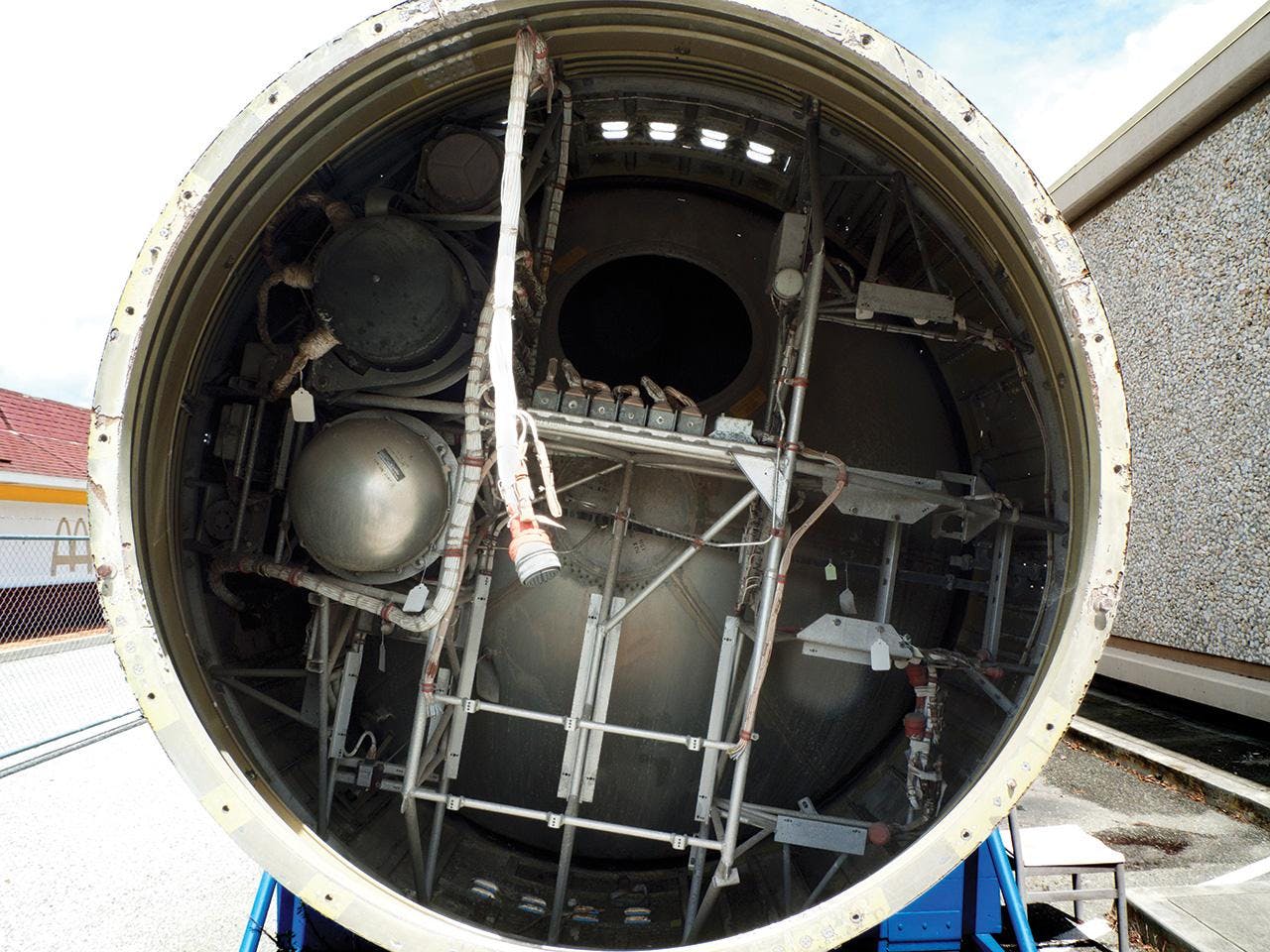

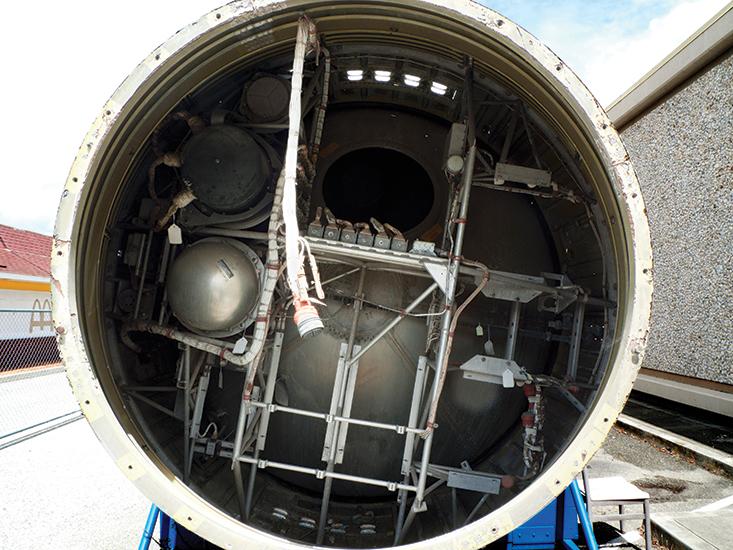

Titan I Missile (McMoon parking lot, NASA Ames) #0415-0415

On my first visit to NASA Ames, my contact took me to see the Titan, sitting in a parking lot next to an old McDonald’s that had been converted into a moon research office. When we reached the nosecone he pointed out an unplugged cable, and asked me to guess what it might have connected to. I was stymied.

The Titan is an intercontinental ballistic missile. The cable was for a nuclear warhead.

I was struck how, up until this moment, I had not consciously contemplated the military aspects of space exploration. Later, when giving a lecture about my process at LACMA, someone asked me if my work is moral. My encounter with the Titan made clear to me that the answer is yes.

Hangar One; Moffett Federal Airfield, NASA Ames #0415-3650

Hangar One was built in the 1930s to house “rigid airships,” à la Hindenburg. It stands 200 feet tall, and covers a footprint of eight acres.

In the best thinking of the times, it was constructed with lead, PCBs, and asbestos, contaminating both the surrounding ground as well as San Francisco Bay. The toxins have all since been removed from the structure, leaving only its steel skeleton.

Hangar One will soon get a second life: It has recently been leased by Planetary Ventures, a Google subsidiary.

Microbial mats, NASA Ames Research Greenhouse #0415-1408

A row of research greenhouses, established in 1999, sits atop the roof of the astrobiology building. This one is filled with trays of cultivated microbial mats of cyanobacteria collected from a field site in Mexico, and maintained in corrosive brines.

One of the most ancient organisms on Earth, cyanobacteria could be similar to simple life on other planets. They could also indicate which organic compounds are associated with the presence of life.

Rachel Sussman is a contemporary artist and author of The New York Times Bestseller The Oldest Living Things in the World. She is a Guggenheim, NYFA, and MacDowell Colony Fellow, TED speaker, and a member of Al Gore’s Climate Reality Leadership Corps.