Few sights on our planet are as recognizable as Egypt’s Pyramids of Giza, the towering trio of monuments built to house the remains of three Old Kingdom pharaohs for all eternity. The pyramids are arguably the most famous human-made structures ever built, and their colossal scale, perfect symmetry and lofty perch on a plateau above the fertile Nile River Valley reflect the divine role that Ancient Egypt’s leaders held in both their lives and afterlives. For years we wanted to see these 4,500-year-old architectural and archaeological monuments but were reluctant to travel to Egypt during the social and political upheaval of the Arab Spring and its chaotic aftermath. Now with tourism there on the rise and hints of increasing stability, we decided it was finally time to view these ancient wonders for ourselves.

The Pyramid Builders

Located in the city of Giza on Cairo’s southwest fringe, the pyramids stand in stark contrast to the bustling city and the surrounding desert. Despite the first, tantalizing glimpse of their pointed peaks that we caught through the smog en route to Giza, we were stunned by their scale and grandeur when we saw them up close the next morning from our hotel balcony.

Built atop the Giza Plateau, whose parched, stony surface rises above the west bank of the lush, palm tree-studded Nile Valley, the three pyramids are the best-known monuments in a necropolis built during the reigns of several generations of pharaohs in the Old Kingdom’s Fourth Dynasty (circa 2575 to 2465 B.C.). This was a time of peace and plenty during which the pharaohs could marshal enough resources and labor—including farmers working in the off-season—to build these immense structures. Their purpose was to house the ka, the portion of the spirit that ancient Egyptians believed remained with the mummified body, along with all the practical necessities—such as furniture, food and means of transportation—considered necessary for the rulers’ afterlives.

The Great Pyramid, the oldest and largest of the three monuments, dominates the skyline with sides that rise an impressive 147 meters above the plateau. Erected by order of Pharaoh Khufu, the second of the Fourth Dynasty’s eight rulers, the Great Pyramid was classified by ancient writers as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—and it is the only Wonder to survive to modern times. Completed in about 2560 B.C., the Great Pyramid remained the world’s tallest human-built structure for more than 4,000 years.

Located a few hundred meters to the southwest, the central pyramid was built by Khufu’s son Khafre, who ruled from about 2520 to 2494 B.C. The smallest pyramid, which Khufu’s grandson Menkaure built, rounds out the trio. Each pyramid is part of a large mortuary complex that included funerary temples, mini-pyramids for each pharaoh’s queens, and a causeway that led to the top of the plateau from a “valley temple” built along the edge of the Nile.

From the hotel balcony, we had amazing views not only of all three pyramids, but also the mythical Great Sphinx of Giza, whose lion’s body and human head, which sports a pharaoh’s headdress, was looking directly at us.

The Great Pyramid

The Giza Plateau, whose flat surface rises more than 100 meters above sea level, is an extension of the country’s vast Western Desert. The bulk of the plateau is composed of stacked carbonate layers deposited from the Late Cretaceous through the Eocene on the floor of the Tethys Sea. This long and narrow ocean separated Africa from Asia following the breakup of the supercontinent Pangea, which began about 200 million years ago. The remnants of this ancient ocean make up the modern Mediterranean Sea.

Khufu and his successors had their pyramids built atop the Mokattam Formation, a series of relatively hard middle-Eocene limestone and dolomite layers that form the surface of this part of the plateau. Many of the blocks that compose the Great Pyramid appear to have come from the same formation, excavated in a quarry a short distance south of the structure. The Mokattam breaks cleanly along bedding layers and is riddled with many vertical joints, so the rock was ideal for dividing into blocks, even with the simple hand tools available to Ancient Egyptian masons.

The scale of the construction is mind-boggling; the Great Pyramid alone consists of an estimated 2.3 million blocks averaging 2.5 tons apiece. The majority of these consist of nummulitic limestone, which contains numerous fossil shells from especially large single-celled marine foraminifera of the genus Nummulites. As you walk around the Great Pyramid’s base, you can clearly see in many of the blocks the round and oblong shells from these creatures, which thrived in the Tethys Sea some 50 million years ago.

The limestone blocks, after being removed from the quarry, were probably dragged overland using ropes and sleds, possibly aided by wet sand to reduce friction. Once at the pyramid’s base, the blocks were likely raised into position using a series of ramps, although this theory remains controversial due to a lack of archaeological evidence. In fact, the near perfection of these ancient monuments, including their alignment with the cardinal directions, has inspired many debates. The designers were clearly master builders; they even figured out an elegant way to use the landscape to their advantage by building both Khufu’s and Khafre’s pyramids around natural hills, which accounted for 23 and 12 percent of their respective volumes, according to a study by French and Egyptian researchers.

After snapping dozens of photos of the Great Pyramid’s exterior and searching for nummulites in its lowermost blocks, we ducked through the small doorway that now marks its tourist entrance. After giving our eyes a chance to adjust to the dark interior, we began ascending a sloping wooden ramp that lines the floor of a narrow tunnel. This soon opened into the Grand Gallery, a soaring passageway about 2 meters wide, 9 meters high and 50 meters long that is lined with smooth, white limestone.

Near the top of the ramp, the Grand Gallery connects to a small passageway that leads into what is believed to be Khufu’s burial chamber. It hosts a lidless, four-ton granite sarcophagus that archaeologists believe was placed there first, with the pyramid later erected around it. Unlike the rest of the monument, where limestone is so prevalent, this rectangular room is completely lined with smooth blocks of medium-gray syenite, a relative of granite that contains less silica. This darker rock, along with the dim light and sarcophagus, creates an appropriately somber mood.

The syenite blocks, which weigh up to 50 tons apiece, were shipped down the Nile from Aswan, more than 800 kilometers to the south. This stone, which is about 600 million years old, is part of the Arabian-Nubian Shield, a group of Precambrian rocks sutured together during the final assembly of Gondwana, the southern supercontinent that joined with its northern counterpart to form Pangea.

After viewing the King’s Chamber, we slowly descended the steep passageway to emerge back into the bright sunshine. Before continuing our tour, we stopped just below the tourist entrance to see a casing layer of glistening limestone, one of the few remaining scraps of the higher-quality, snow-white Tura Limestone that once covered the lower-quality blocks quarried nearby. Although much of this smooth casing was later removed to incorporate into other construction projects, the pieces that remain, including a large, gleaming patch at the top of Khafre’s pyramid, offer a tantalizing hint of what the three pyramids looked like following their completion four and a half millennia ago.

Secrets of the Sphinx

In contrast to the pyramids, the Sphinx was carved directly out of the Giza Plateau’s limestone bedrock. And because the layers here tilt about 10 degrees to the southeast, the famous statue was, despite its lower perch on the plateau’s eastern edge, sculpted out of the same Mokattam Formation of which the pyramids were constructed. The Sphinx stands guard over Khafre’s Valley Temple, which was originally located alongside a now-vanished canal that connected the complex to the Nile and through which pyramid construction equipment and materials were transported.

The Sphinx was carved from three subunits of the Mokattam, and each subunit offers a glimpse of how variable the conditions were at the bottom of the Eocene Tethys Sea. The paws are part of the lowermost, and hence oldest, subunit, which consists of brittle material from an ancient, petrified reef. Most of the body was sculpted from a stack of alternating soft and hard layers that reflect small changes in water depth, grain size and depositional energy in an ancient lagoon environment. The Sphinx’s head and neck were carved from a harder limestone unit, which is why the face is so much better preserved than the body. Despite the general durability of limestone in arid climates, the Sphinx has frequently required repairs (beginning, according to New Kingdom records, at least as early as 1400 B.C.) The statue has continued to deteriorate from various causes, including vandalism, the misuse of grout, and a recent rise in groundwater levels caused by irrigation and leaking sewage. This rise is believed to have weakened the statue’s foundations and caused wicking of moisture up through the Sphinx to its surface, where evaporation causes material to flake off, grain by grain.

For all we know about it, the Sphinx still harbors several secrets, including when it was carved and whose countenance is mounted on the lion’s body. Some scholars have speculated that it represents Khafre, builder of the central pyramid. Yet despite his having left behind such an impressive monument, only one known depiction of his face has been found (on a small statue that you can see in the fabulous Egyptian Museum, which also has an extensive exhibit of King Tutankhamun artifacts), so the likeness is difficult to judge.

Sakkara, Dashur and the Citadel

Although the Pyramids of Giza are by far the most famous ancient Egyptian tombs, their construction would have been impossible had several earlier pharaohs not conducted some innovative architectural experiments at nearby sites, including Sakkara and Dashur, two other Ancient Egyptian royal burial grounds that are easily reached.

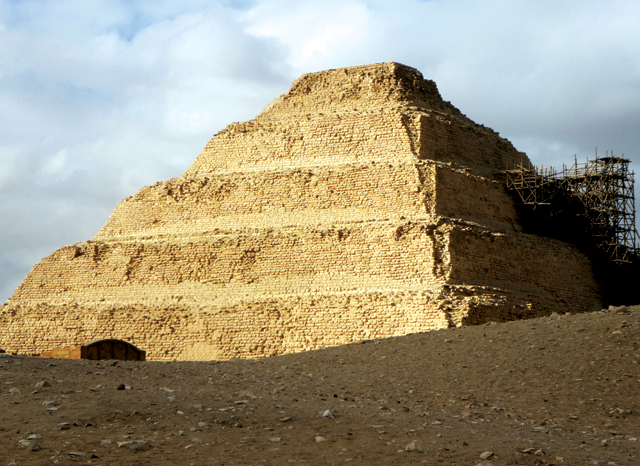

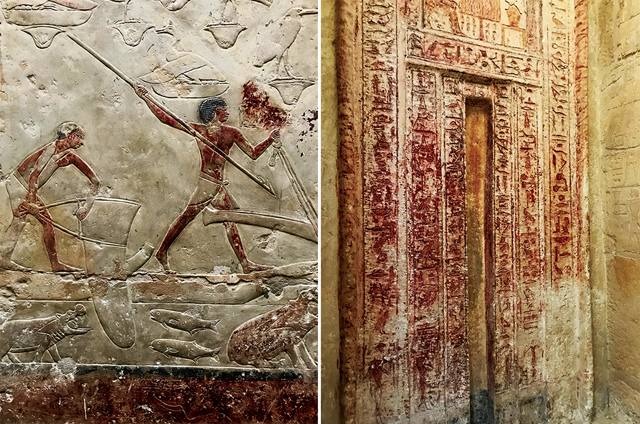

Early in the civilization’s history, royal tombs (called mastabas) consisted of subterranean burial chambers covered with rectangular, flat-roofed stone structures. During the Third Dynasty, under the reign of Pharaoh Djoser, an architect named Imhotep designed a new type of tomb that mimicked a series of six stacked mastabas. Completed in about 2630 B.C., the so-called Step Pyramid, which historians generally consider Egypt’s first, dominates the necropolis at Sakkara, an important archaeological site about 23 kilometers south of Cairo. Located near the ancient capital of Memphis, which was strategically situated near the mouth of the Nile River Delta, this royal burial ground came into use during the First Dynasty around 3100 B.C. In addition to the Step Pyramid, the site hosts thousands of burial tombs spanning most of Egypt’s dynastic period.

It’s easy to combine a trip to Sakkara with an excursion to Dashur, where you can see the Red Pyramid built by Khufu’s father, Snefru. Named for the reddish limestone blocks used for its core, this structure was the first smooth-sided pyramid and is one of three this pharaoh built. Another, the nearby Bent Pyramid, developed cracks as it was being constructed, forcing ancient engineers to reduce the slope of the sides midway through construction and creating its characteristic “bend.”

Like Khufu’s and Khafre’s pyramids, the Red Pyramid was also originally cased with gleaming Tura Limestone. This was quarried on the east side of the Nile near the center of modern-day Cairo. You can catch a glimpse of the quarry while visiting the beautiful Citadel of Salah El Din, a medieval fortification completed in 1183 A.D. While there, you can tour the impressive Ottoman-style mosque built between 1830 and 1848 by Pasha Muhammad Ali, who is considered the father of modern Egypt.

Given the political tumult currently enveloping parts of the Middle East, we almost decided to forgo a trip to Egypt. We were finally swayed by our kids’ organized lobbying campaign, including their comprehensive list of pros and cons. As we stood at the Citadel and peered through the smog of modern Cairo at the Pyramids of Giza in the distance, we were glad that we’d chosen to come. We didn’t experience any problems, every Egyptian we met welcomed us warmly, and now we’ve seen the world’s grandest monuments from human antiquity.

Getting There and Getting Around Cairo

Egypt’s main gateway is Cairo International Airport (CAI), which has nonstop flights to most major Middle Eastern and European cities. EgyptAir offers direct flights to Cairo from New York City and Toronto. From other North American locations, it’s usually most convenient to fly through Dubai, Abu Dhabi or a European hub. British Airways, Emirates, Etihad, Lufthansa and Turkish Airlines are among the carriers offering connecting service.

After landing at the airport, U.S. passport holders must obtain a 30-day tourist visa, which costs $25 per person and is payable only in cash in U.S. dollars. According to the Embassy of Egypt website, Americans should also bring extra passport photos and copies of the completed visa application and passport information pages, although we were not asked for this additional documentation.

If you’re heading directly to Giza, most accommodations will arrange transport from the airport northeast of Cairo to the pyramids, which are located southwest of the city. Depending on traffic, it can take more than an hour to travel between the two. Suntransfers.com also offers door-to-door transfer service. For other transportation in Cairo, we don’t recommend driving yourself as the city’s traffic can be chaotic. Instead, consider hiring a driver. This service should also be included in any private tour.

During winter it’s advisable to book accommodations ahead of time, especially if you want to stay close to the pyramids. Egyptian hotels range widely in price, services and quality but are generally a better value than in the U.S. Located near the entrance to the pyramid complex, the plush Marriott Mena House offers luxurious accommodations with up-close views of the Great Pyramid. If, like us, you’re willing to forgo luxury for a basic, clean room, the Pyramids View Inn boasts one of the very best views of all three pyramids and the Sphinx from its balcony. From there you can also watch the sun rise and set, eat breakfast, and enjoy the colorful (though hokey) sound and light show that illuminates the pyramids nightly—all for free.

To enter the Great Pyramid, you must have two tickets: one to visit the necropolis and a second to see the inside of the pyramid. The latter are timed for either the morning or afternoon and best booked in advance through a tour guide or your accommodation. Egypt’s currency, the Egyptian pound, is available from ATMs throughout the city, and U.S. dollars are also widely accepted. Although most accommodations accept credit cards, it’s a good idea to have some small bills handy for tipping.

The weather is typically sunny but chilly during winter, while the heat is scorching in summer, so the best time to visit is from October through March. Before you head to Egypt, it’s a good idea to check with the U.S. Department of State for current travel advisories and sign up for the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program to receive alerts.

Lead image: The Pyramids of Giza, near Cairo, Egypt, are perhaps the most famous structures ever built. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

This article was originally published in Earth Magazine on August 16, 2018.