It’s 9 a.m. on a typical morning in Chengdu and I’m awakened by the sound of my phone alarm. The phone is in my study, connected to my bedroom by sliding doors. I turn off the alarm, pick up my phone, and, like millions of people in China, the first thing I do is check my WeChat. At 9:07, I send my first message of the day.

WeChat, the brainchild of Tencent—one of China’s big three tech giants—is often referred to in the West as a social media app, something equivalent to Facebook or WhatsApp, but that’s to undersell it. WeChat has over 1 billion active users. In China, people don’t refer to it as a social media platform but rather as a social ecosystem. The features are seemingly endless. Beyond the typical social media functions of messaging and a Twitter-style feed called “friend circle,” it can be used to make payments for almost anything. Because developers can slot their apps directly into WeChat and tie them into the social and payment functions, it acts like a very sleek and efficient operating system. If it wasn’t for the fact that I grew up in London and use a VPN to jump the great firewall to keep in touch with my friends at home and use Google, I could go entire days without leaving WeChat.

At 9:27, once I’ve brushed my teeth, answered a few messages, and wiped the sleep from my eyes, I order a coffee through WeChat. There’s a payments window on the app, and when you click on it you see various options, some proprietary to WeChat and some which are independent apps that run on WeChat’s platform. I open the Meituan delivery app and scroll through all the coffee options around me. I order an Americano. I have my WeChat linked with the facial recognition scanner on my iPhone; when I pay, I just hold my phone up to my face and a green tick flicks across the screen. Seven minutes later, I get a message telling me the coffee is on the way, with the name and number of the delivery driver. It arrives at 9:53.

Before 10 on a normal day in Chengdu, WeChat knows the following things about me: It knows roughly when I wake up, it knows who has messaged me and who I message, it knows what we talk about. It knows my bank details, it knows my address and it knows my coffee preference in the morning. It knows my biometric information; it knows the very contours of my face.

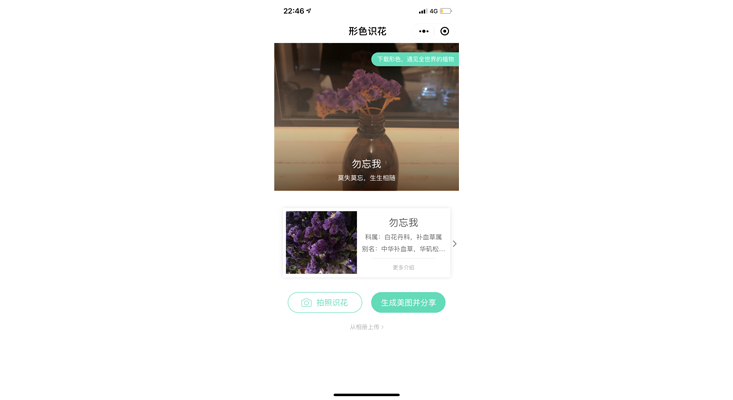

But this isn’t all it knows. I use WeChat to pay my rent. I use it to pay for my utilities. I use it to top up my phone credit. I use WeChat to pay for the metro system. I use it to scan QR codes on the back of shared-bike schemes throughout the city. I use it to call cabs. It knows where I go and how I go there. I follow bloggers on it, I follow media organizations and NGOs and government offices (there are over 20 million official accounts associated with governmental institutions, agencies, or officials) and I read their content through it. It knows what academic interests I have—I’m researching mental health and I pay for and attend online courses in psychology through the app. I book movie tickets, order things through Jingdong’s page (the Chinese Amazon), and I recently downloaded a WeChat app which allows me to take a photo of a flower and have it tell me the name. It also tells me anytime it’s been mentioned in Chinese poetry.

WeChat knows what I am reading. It would discover I am doing research for this article.

Then there are the features I don’t use. I could get a loan through WeChat. I thankfully haven’t had to book a doctor’s appointment through WeChat yet, but if I did it would know what afflicts me. I’m not married but those who are can, if they must, book divorce proceedings through WeChat.

All this is to say that WeChat has metastasized into every aspect of people’s lives in China. The scholar Yujie Chen, a lecturer in Digital Media and Communication at the University of Leicester, who has written a book on WeChat, calls it “super-sticky” because of the way that it has managed to make itself inextricable to so many aspects of daily life in the country. According to one estimate, WeChat alone ploughed $50 billion into the Chinese economy in 2017.1 It is the ultimate in data centralization and because of the nature of the digital economy the more data it has the more efficient it becomes—and the more easily it can pivot into new markets.

Research by Seagate and IDC group, a data intelligence firm, has recently announced that by 2025 China will hold 27.8 percent of the world’s data, compared with 17.5 percent that will reside in the United States. This data will also be far more concentrated in an even smaller oligopoly of titanic tech firms, making it even more useful for the development of artificial intelligence and the next generation of big-data technologies. While it is true that all the data I share with WeChat I also share with Google, Amazon, Uber, Twitter, and Instagram, WeChat is unique in that it has managed to capture all of the functionalities that these companies do separately in the West. By co-opting their Chinese equivalents into its social ecosystem, it swallows all of the data they generate.

As debates rage in the West about the extent to which we are comfortable with tech monopolies and what happens with our data, WeChat provides a window into a world of almost total data-centralization.

The word 隐私 yinsi, which is often how privacy is translated, is an imperfect match for the English term and reads more as something that is secretive or needing to be hidden. Something that is private in English is inherently neutral, as it is assumed in our individualistic society that there should be spaces beyond the reach of governments, corporations, or others. In China, where society is more collective, family units less atomized, and a long history of the government being minutely involved in all aspects of a person’s life, the private realm is far less demarcated.

The irony of WeChat is that part of its initial success as a platform was predicated on the idea that the user interface provided more privacy than that of its rival Weibo. While Weibo functions much more like Twitter—posts can be viewed by anyone and users have visible follower counts and their public influence is more easily gauged—WeChat initially functioned more as a private messenger along the lines of WhatsApp. Later features like friend circle, which allow posts to be viewed by all of a person’s followers, were more private in the sense that only once your friend request had been accepted could you view that person’s posts. You can’t view the number of likes under a post; you can only see if mutual friends have liked them. You can also create groups on WeChat and broadcast within them to people outside of your friend circle, but they are capped at 500 people.

People are regularly arrested for messages they send in “private” group chats.

In 2013, after Xi Jinping emerged as China’s leader and started to draw tightly on the reins of power, one of his early moves was to invite a number of “big V” account holders2 (verified Weibo accounts of celebrities and popular bloggers with thousands or millions of followers) for “tea”—a euphemism for a stern talking to from the central government—and to publish new guidelines which said a post viewed over 5,000 times that offended government sensibilities such as “damaging the national image” and “causing adverse international effects” would lead to three years in prison.3 There was a swift exodus from Weibo toward WeChat as the latter was deemed politically safer because of its more closed and intimate design.

This design feature, which came out of the demands of a heavily censored Internet environment, is ironically finding its adherents in the Internet free-for-all of the West. Facebook’s recent announcement to push for a more private user-experience lead many commenters to note that the reformed Facebook sounded a lot like WeChat.4

Despite WeChat’s somewhat more private design, Amnesty International, in a 2016 report on user privacy, gave WeChat zero out of a 100 for its lack of freedom of speech protection and lack of end-to-end encryption. By comparison, Facebook scored 73. People are regularly arrested for messages they send in supposedly “private” group chats. In 2017, two people were arrested in Nanjing for separate instances of making satirical comments referring the massacre in the city by the Japanese in 1937.5 One person, seeking a job in the city and down on his luck, wrote in a group for job-seekers that “Nanjing is a pit. We should let the Japanese come slaughter again.” He was detained two days later. A similar case that same year saw a 31-year-old man jailed for joking about joining the Islamic State in a group-chat. He was arrested under China’s anti-terrorism laws and given a 9-month prison sentence.6

In 2017, regulations were passed that said the “owners” of WeChat groups are legally responsible for content posted by other members, and that complete chat logs should also be stored for potential police use for a period of at least six months.

Despite its user interface being more private in a general sense than Weibo, the fact that it is censored is widely known and has been a point of contention in its wider plans for global expansion. The Citizen Lab, an interdisciplinary lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, at the University of Toronto, reports that WeChat’s censorship is stronger for people who are registered with a domestic phone number.7 Messages and photos that won’t show up for a person who registered in China might show up for a foreigner. Today, you don’t know when a message has been censored. In earlier versions of WeChat, a message would show up and tell you that your message had been blocked for containing keywords that violated certain laws and regulations of the PRC (People’s Republic of China). Today, messages just don’t appear at all. You’ll only know if you compare your chat log with that of the sender.

Despite this reality, there is a nascent privacy awakening in China. A number of domestic scholars wrote that 2018 was a landmark year in both awareness of privacy and the construction of a legal regime to protect personal data.8 But this conversation isn’t about privacy from the government—that is a moot point in the context of China. Rather, the privacy debate is about what happens to your data. As Yujie Chen notes, part of the driver behind the privacy awakening in China is a global trend in which people “now understand the business model of the internet companies—that is, selling individual’s data.”

In China, where there has until only recently been little in the way of legal protection over personal data, it is common for granular private information to be sold by tech companies to third parties who use them for targeted advertising. The artist Deng Yufeng exposed this reality in his solo show at the Wuhan Art Museum in 2018, where he displayed the private details of over 300,000 people—their addresses, names, bank numbers, and phone numbers—that he had bought online from data they had shared willingly to a tech company which had sold it on without their permission. “Do we have any secrets anymore?” a neon-panel asked in the final room of the show.

Combating this trend has led the Chinese government to issue comprehensive data privacy rules. In May 2018, the government issued a “Personal information security specification,”9 a standard for enhanced privacy, and an auditor affiliated with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology published a list of 14 mobile apps that had “excessively collected sensitive personal data” without user consent.

The new data rules, however, underscore how privacy in China is not the same as in the West. Advocates here warn that an individual’s rights to privacy, free speech, and a free press—the principles of democracy—are undermined by government surveillance. In China, privacy rules are designed to curtail private companies from collecting and profiting from data. The Chinese government retains the right to use it for political purposes, such as quelling public protests before they happen. Still, to the extent that the Chinese government is increasing privacy protections on my data on WeChat, the user experience is little changed. Nothing has changed with how I use the app or how much data I willingly hand over to it.

At 10:44 a.m. in Chengdu, I get a text from yidong, the mobile service provider I use, to say I am out of credit. When I see the text at 11:04, I pay my phone bill immediately through the payments page on WeChat. At 11:15, I walk to a yoga class. I had asked the teacher, via WeChat message, a few days before if the class was still happening because of spring festival. I check in at the gym with WeChat and then for two hours WeChat doesn’t know exactly what I am doing since I put my phone in my locker—but it would be able to make a fairly good guess. As I leave the gym I get a coffee at 1:30 p.m. and open some articles my friend has sent. They open within WeChat—there are no external links within the WeChat universe—so WeChat knows what I am reading. It would discover I am doing research for this article. I am reading about WeChat.

The data that WeChat creates is a boon for the government. On an aggregate level, WeChat provides “heat-maps” that can show the government in real-time how many people are using the service based on location data, which allows them to predict and outrun mounting protests or build-ups of people. On a granular level, the government has exemptions from data-protection laws which anonymize data and which, supposedly, prevent companies from singling out specific individuals from their wider data pool.10 WeChat’s encryption doesn’t prevent the government from being able to use the data as it sees fit. Legally, WeChat’s terms and conditions allow for user data to be retained “as long as is necessary” to “comply with laws and regulations.” Tencent doesn’t disclose when the government requests user data and gives no detail of the kind of encryption, if any, it employs.

Today we are our own informants, writing the most detailed personal accounts ever collated.

At around 4 p.m., I have a problem with a money transfer. So I call the bank branch where I opened the account in the northeastern city of Dalian, a full four hours away by flight. The bank teller tells me that I was getting money from an institution (a scholarship from my university in the United Kingdom), so I need to prove my student credentials before they process the transfer. She adds me on WeChat, using the phone number I’d called into the bank, and I send her all the relevant documents. She processes the transfer and sends me screenshots of her authorizing the money to be sent into my account.

Hyper-centralization makes life convenient. It also presents a worrying potential for fraud. On a typical day I’ve paid my phone bill, sent money to people, bought groceries, and even sent authorized documents to the bank, all through one app, protected by one password and kept intentionally unencrypted to comply with government data-sharing regulations.

It is extremely difficult to gauge the number of accounts that get hacked on WeChat per year (Tencent declined to comment for this article). But the scope of the problem of online fraud in China is widespread. In a survey held by Internet Society of China, an NGO made up of 1,200 members, including key Internet leaders in the country, 84 percent of respondents said they had suffered some sort of data theft. In 2016, the death of Xu Yuyu, an 18-year-old girl whose family was defrauded of the savings they’d accumulated for her to go to university, sparked a debate about data privacy.11 A court ruled her death, by heart attack, had been the direct result of the fraud. A man was sentenced to life in prison for paying a hacker to steal her private details.

Moreover, the data centralization that has enabled WeChat to map itself neatly onto users’ personal and commercial lives, has now created an opportunity for the government to step in and invite it into their political lives. Beyond sharing data with the government, WeChat is now rolling out a digital ID card. Every Chinese citizen is issued an ID card. It functions like a domestic passport and is needed for any interaction with the state—at hospitals, booking trains, flying domestically, or making bank transactions. In Guangzhou, the provincial government has already debuted a WeChat ID card and there are plans for it to be rolled out across the whole of China. Hijiacking WeChat in the future could grant a hacker everything from a user’s government-approved identity to his or her bank details, address, and coffee preferences.

WeChat’s data centralization makes it a cornerstone of the government’s social-credit system that is feted to appear nationwide in 2020. Mooted in 2014 in a document entitled “Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System,” the plan is to build a system that incentivizes good behavior and punishes that deemed unconducive to the construction of a harmonious society or, as the document itself dictates, a system that will “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.”12 Under the pilot scheme, people with outstanding court orders or who have defaulted on loans can’t book high-speed rail tickets and can’t fly in planes.

The nationwide social credit system will be compiled by combining government records with commercial profiles. At present, Ant Financial, the finance-arm of Alibaba, China’s Internet conglomerate, has rolled out “sesame credit,” which gives people a score out of 950 based on their punctuality paying back loans, their purchase history, their social networks (having friends with high scores boosts your own score), and data shared from the government such as court-orders and fines. People with high-scores get preferential loans, can rent cars without deposits and are even guaranteed visas for countries like Luxemburg and Singapore, among other perks. China Rapid Finance, which is partnered with Tencent, is responsible for creating a similar scheme off the back of WeChat data.

So, what does this mean for me? It isn’t clear yet how the social credit system will play out for foreigners in China. My sesame-credit score is a paltry 570 and China Rapid Finance hasn’t made its social scores available to view yet. There is, however, already a feature on WeChat that has been rolled out in Hebei province. It shows you the deadbeats in your vicinity—a literal map, dotted with clickable icons of anyone within 500 meters of you who has failed to pay back a loan recently.13 It also shows their national ID numbers and explains why they’re being named and shamed.

I often hear people repeat the refrain, both here in China and in the West, that they have nothing to hide, so they have nothing to fear from the data that they’ve handed over. In the West, where we have a neo-liberally informed suspicion of government, we’ve gladly handed over our data to corporations, believing them to be benign. Amazon already has a system that installs a digital key on people’s homes that their delivery drivers can open to ensure safer deliveries.14 People then buy an Amazon cloud cam to watch the delivery in real time.

It is only in the wake of scandals such as Cambridge Analytica and the Russian leveraging of social media to influence the 2016 election that we have started to question whether this trust might have been misplaced. In China, where people have a different relationship to privacy and a tacit understanding that the government was always going to take hold of this data once it became available, voices in dissent are muted.

The problem is WeChat is vulnerable. I don’t know what I’d do if my account was hacked today; and this is without WeChat being my government issued ID and prior to it influencing my social credit score. I may have nothing to hide, but that presupposes two conditions; one, that I understand where society stands on a particular behavior or thought and that I am on the right side of it (and that the line won’t move once I’ve chosen where to stand), and secondly that I know what I am supposedly hiding.

WeChat has read every-single message I have ever sent and hasn’t understood a single word. Who knows what the algorithms flag in my daily life; how it chooses to interpret my interactions and to what end? I’ve said that WeChat knows what I read and where I took a cab to last night, but that isn’t quite accurate. It has data about all of this, but knowledge implies understanding and interpretation—and that will be done by someone else, with their own ulterior motives. Perhaps you have nothing to hide from WeChat, but you might from whoever ends up with your data.

The author Timothy Garton Ash was a correspondent in East Germany during the time of the Stasi secret police. After the fall of the Berlin wall, he wrote a moving account, The File: A Personal History, of re-reading the information the Stasi collected on him. “Like the materials used in a collage, these pieces of evidence have very different textures: here a fragment of hard metal, there a scrap of folded newspaper, there again a wisp of cotton-wool,” he wrote, marvelling at the details he himself had forgotten of his life in East Germany but that seemed so relevant to the security forces and their web of informants. He concluded that what the files ultimately presented were “a vast anthology of human weakness,” predicated on turning approximately 1 out of every 100 members of the overall population into informants.

Today we are our own informants. We have written our own digital files and diligently update them with the most frighteningly detailed accounts ever collated in human history. We have created an infinite anthology, but of what?

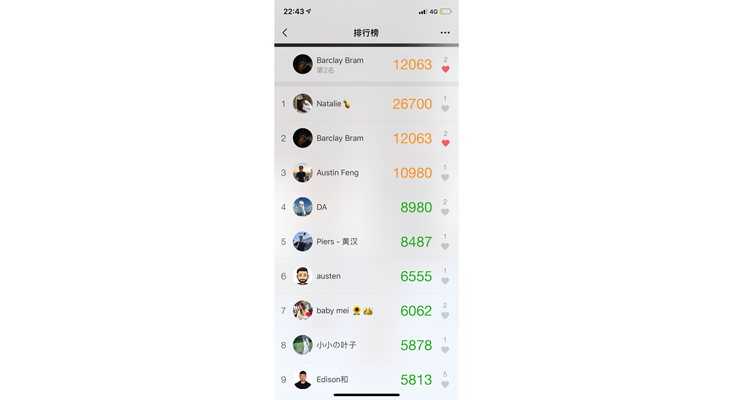

A few weeks ago, a friend showed me a feature on WeChat that I hadn’t realized existed. We Run links up your account with the activity monitor on your iPhone and measures your steps. At the end of every day, WeChat broadcasts the number of steps I’ve walked and ranks me against my friends. Since friending a herder I met on a hike in the Tibetan foothills I’ve given up ever coming in first place. On that day in February I ranked 30th overall among my friends, even though I’d decided to walk to and from a restaurant with a friend to boost my score.

In total I had walked 10,771 steps. WeChat had been with me every step of the way.

Barclay Bram is an anthropology Ph.D. candidate at the University of Oxford’s School of Global and Area Studies.

References

1. Iqbal, M. WeChat Revenue and Usage Statistics (2019). businessofapps.com (2019).

2. Muncaster, P. China’s ‘Big Vs’ disown selves online to avoid new gossip laws. Theregister.co.uk (2013).

3. Guilford, G. In China, being retweeted 500 times can get you three years in prison. Quartz (2013).

4. Yuan, L. Mark Zuckerberg Wants Facebook to Emulate WeChat. Can It? The New York Times (2019).

5. Davis, K. More Nanjing Miscreants Detained by Police. Sixthtone.com (2018).

6. Zheng, S. Comment about Islamic State on social media lands Chinese man in prison. scmp.com (2017).

7. Ruan, L., Knockel, J., Ng, J.Q., & Crete-Nishihata, M. One App, Two Systems. citizenlab.ca (2016).

8. Sacks, S. & Laskai, L. China’s Privacy Conundrum. Slate (2019).

9. Xia, S. China’s Personal Information Security Specification: Get Ready for May 1. Chinalawblog.com (2018).

10. McLaughlin, H. We(Chat) The People: Technology and Social Control in China. Harvardpolitics.com (2017).

11. In China, consumers are becoming more anxious about data privacy. The Economist (2018).

12. Botsman, R. Big data meets Big Brother as China moves to rate its citizens. Wired.co.uk (2017).

13. Shen, X. “Deadbeat Map” shows which people around you are on a financial blacklist. Abacusnews.com (2019).

14. Liao, S. After trying your front door, Amazon wants to let people deliver packages inside your garage. Theverge.com (2019).

Lead image credits: gyn9037 / Shutterstock; Freepik