In Oyster, Virginia, mailboxes and their posts are covered in oyster shells. Oyster shells have been tossed in the sandy dirt along driveways and piled around the bases of the pines. One can imagine the dirt is composed largely of the shells, made brittle and whitened by the sun and wind over time, crushed underfoot into a fine powder.

I was there at the end of August, and the heat was stunning. Oyster lies on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, the southernmost portion of the Delmarva peninsula: a substantial spit of coastal plain that juts down from Delaware and Maryland, hugs the Chesapeake Bay like a thick arm.

The brackish oyster would hear the rhythm of the tides like breath, or a heartbeat.

I walked under shortleaf pines, my breath slowing to echo the sighing waves. On the ground lay a still-whole oyster shell that had, uncannily, the exact shape of an ear. The indentation where the adductor muscle had been looked like the ear’s opening. Each curve of the shell’s margin resembled the way an ear flowers outward: a concavity that seems to want to hold the world within it, to cradle it somehow.

Upon a spit of land, surrounded by the rising sea, I listened.

In ocean lives the ancient Greek Okeanos: a great river encircling the earth, a god. “When the sea is worked into anger, it possesses equal energy across the entire audible spectrum; it is full-frequencied white noise,” writes the soundscape ecologist R. Murray Schafer in The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. “The impression is one of immense and oppressive power expressed as a continuous flow of acoustic energy.”

But then there is the shore. Schafer continues:

The sea symbolizes brute power; the land, safety and comfort. … Thus, as we move back to the shoreline, power gives way to regular beating and, in a miraculous manner, the sea begins to suggest its opposite—the discrete side of its signature—rhythmic order. Rhythm replaces chaos as the sea becomes benign.

This is what the brackish oyster would hear, the rhythm of the tides like breath or a heartbeat at the edge of the sea. Oysters don’t have auditory organs, but with small tentacles at the edge of their fleshy mantle, they are able to sense light, the salinity and temperature of the water—and vibration. In this way, they “listen” to the conditions of their environment, sense the world around them. They look like congregations of ears, huddling along the shores, in bays and estuaries, at the mouths of sluggish tidal rivers, near where people live.

Life first came to form beneath the ocean’s surface. Within the deeps, the first ears listened. Some animals crawled out of that wash of sound and evolved inland, on soil, sounding through air. The ocean still contains most of life on the planet, but us creatures with lungs can’t live there now. We have to live rooted, terrestrial.

In The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh writes that, “Through much of human history, people regarded the ocean with great wariness. Even when they made their living from the sea, through fishing or trade, they generally did not build large settlements on the water’s edge.” London, Lisbon, and Europe’s other great port cities “are all protected from the open ocean by bays, estuaries, or deltaic river systems.” The places where oysters live. Oysters were historically part of the reason that bays and estuaries were protected from the sea’s brute power. Their reefs buffer coastal communities from storm surges and erosion, from the ocean’s chaos, its “full-frequencied white noise.”

Oyster shells contain calcium carbonate that “sweetens” the soil, boosting its microbial and invertebrate life, so that one might raise a handful of fertile dirt to the ear and hear it crawling: the foundation of our lives on the earth, humus, sharing a root with human.

In 1701, a Swiss explorer sailing in the Chesapeake wrote, “The abundance of oysters is incredible. There are whole banks of them so that the ships must avoid them.”

When colonists from the Virginia Company landed on these shores in 1607, large communities belonging to the Powhatan Confederacy dwelt along the coast. People waited on the fall of the tides each day, listening for the suck of receding saltwater from the reefs and marshes. The reefs were made of oysters clinging to one another in the millions upon millions. In the peaceful quiet of low tide, people would walk out along the tidal channels to pluck the shells loose. They roasted them over crackling fires until the bivalves’ two halves popped open to reveal the meat inside. When the shells were emptied, they tossed them into piles.

Archaeologists have long called these shell-heaps “middens,” which means literally “dungheap.” But more recent studies suggest that the middens were more like temples. Nearly all records of early pottery throughout the Southeast, for example, are found with the midden-temples. The shells were used to temper pots that served as vessels for feasting. It’s now thought that both the shells and pots, concave in shape, womblike, signified abundance. So whereas anthropologists once thought oysters were “starvation food,” they now recognize them as “feasting food,” a delicacy in celebrations such as marriages and in rituals like burials. The anthropologist Cheryl Claassen writes that they were symbols of both fertility and renewal: everlasting life.1

Cultural meanings of the oyster transcend specific shores. In Greek myth, the oyster shell represents Aphrodite, the goddess of fertility, beauty, sensuality. When the sky god Uranus’ testicles fall into the sea, Aphrodite is born from the foam of the waters (aphro- meaning foam) in an oyster shell and sails on it to land, the island of Cyprus. The oyster, then, is associated with life rising from the vast ocean and making a home on land.

Aphrodite embodies life on a planet whose lands are surrounded by ocean, then. In her goddess body, life is a pleasure and passion, beautiful, while oysters give birth to more life because they are an aphrodisiac, a word with the same foamy root as the goddess’s name.

By the 1850s, settlers industrialized the oystering that was once done by hand. As the century accelerated, dredging boats dragged great metal claws through the Chesapeake’s oyster beds, feeding commercial canning operations and decimating the reefs. Before settlers came, the Powhatan conducted oystering as a ritual activity; now it became an intensive industry in the burgeoning capitalist nation. Suddenly oysters did not symbolize biological fecundity but industrial development and economic affluence.

At the Barrier Islands Center Museum in Machipongo, a few miles from Oyster, there were replicas of one-gallon cans of “Delicious Oysters” on shelves, and of oysters on enameled platters with silver forks, an oil lamp on a lace doily at the center of the table. On a credenza, an early 1900s Sears catalog was spread out; I flipped to the section of Truphonic phonographs, encased in polished mahogany and walnut cabinets, testimony to that era’s newfound taste for music as a product for consumption.

Oyster reefs protect coastal communities from storm surges and erosion, from the ocean’s chaos.

Scholar Jonathan Sterne writes in The Audible Past that the sound-recording technology that arose in the late 1800s was touted as a way to preserve “the voices of the dead.”

The “culture of preservation” from which the phonograph arose and gained popularity was a culture that had recently learned to embalm bodies, and to can food.

The mass production of tin cans enabled the large-scale distribution of industrially canned foods. Sterne writes that canned foods were “an early artifact of an emerging consumer culture.” Canned oysters could be shipped anywhere, just as recorded music would soon be a vessel for the voice to travel far across the distances of time and space.

“By 1850,” writes Sterne, “gold miners in northern California were eating large quantities of canned fish, shellfish, tomatoes, and peas.” The extractive oystering industry, then, in turn fueled the extractive Gold Rush, the shelves of miners’ shacks in the remote backcountry of the West lined with Virginia oysters as they dug for veins of gold and pushed toward the final frontier of Alaska.

Between 1876 and 1883, in the first years of the phonograph’s existence, the density of oysters in the bay fell by 64 percent—“among the largest documented declines of a previously widespread marine species,” wrote researchers in a 2011 Marine Ecology Progress Series article.2 In 1906, when John Philip Sousa warned of “canned” music, a time when “everyone will have their ready made or ready pirated music in their cupboards,” consumers purchasing music and no longer making it, it was within this context.3

In the early 1900s, oyster “tongers” who harvested with small hand rakes sounded the alarm that the bay would be empty of oysters in the next few years if the dredgers continued. But no one listened to them. Tongers as a demographic had far less money than the dredgers who could afford the industrial means of extraction, and money has a way of amplifying voices, expanding their reach, while the lack of it is a silencing force.

But an adult female oyster can produce 60 million eggs in a year. Oysters still live off the Eastern Shore of Virginia, even if their numbers are just 0.3 percent of their “virgin” abundance; they are fecund creatures. A person can hear them. That’s what I had come here to do, in fact.

With the Coastal Futures Conservatory, I would listen for oysters.

The Conservatory’s website had made me perk my ears, with the tagline “Listening for Coastal Futures” and its sound sample of a foamy roar from the ocean. Founded in 2018 by composer and eco-acoustician Matthew Burtner, it is a kind of ongoing experiment conducted within the Virginia Coast Reserve’s 14 barrier islands and 40,000 acres of intertidal channels. Created by The Nature Conservancy in the early 1970s, the Reserve is the largest stretch of wilderness on the United States Atlantic coast—another iteration of a “culture of preservation.”4

“We pivot from the ocular metaphor of an observatory to the aural metaphor of conservatory,” the website read, “in order to emphasize our focus on listening.” The Coastal Futures Conservatory strives to be “a school of music that teaches participants how to listen to and compose with the living world.”

A professor of music at the University of Virginia, Burtner was bringing his summer class, called “Soundscapes of Restoration,” to the coast, and he had told me I could join them. On the covered wooden deck of his school’s coastal research center, he introduced me to his students. They were landscape architects, environmental scientists, scholars, and musicians.

He had issued each of them a field recording set with recorder and headphones. They would collect sound recordings to use for their multimedia art projects for the class. As a group they would also set up audio equipment to record the coastal environment and contribute to the long-term ecological research program at the center.

In a shed, the students and I chose wetsuits and squeezed into them, pulled on rubber boots that rose to our shins. We grabbed life jackets and clomped down the path to the docks, where the boats were waiting.

“We follow the tides,” Burtner said, and now was the time, low tide.

Offshore of an island called Wreck, the captains anchored the skiffs. We slipped into the shallows and waded to land. Stepping ashore, gray shells crunched underfoot. It was a harsh sound that made my teeth ache. I looked down to see that the shells composed all of the land I stood on. Each of my steps sunk into piles of shells that looked like pottery shards. Ahead, oyster shells were bunched together in masses that protruded vertically, like otherworldly bulbs pushing up from the mud. We stood on one of the reserve’s oyster reefs as it slowly became more exposed at low tide. Like forests that are fed by the rot of leaf litter, oysters latch to the calciferous remains of the dead who lived before them.

“Oyster larvae, which don’t have shells yet, have a special sensory ability to chemically sense the shells of mature oysters so they can attach to them,” one of the captains told me.

Shells clattered as I walked along the island’s edge. Oyster shells are drab, irregularly shaped, rough to the touch, knobby: not pleasing in the way of cockles or whelks or periwinkles, or even limpets, the ones I love to gather along sandy shores. They are gray, the color of pencil lead, sometimes slate-gray like chalkboards. Some are white as bone.

The students scattered to wander and make field recordings for their projects, dropping their hydrophones down into the water or holding their covered microphones up to the seawind. A gull laughed and shrieked. Small waves lifted then slapped down onto the reef, the shells clacking as the waves sucked backward and drew away. I puttered along, just the gravelly crunch of empty shells, bending now and then to touch one, turn it over.

In a chapter on oyster-gathering in Stalking the Blue-Eyed Scallop, forager Euell Gibbons wrote that “a broad spectrum of life” in the intertidal zone consumes the eggs and larvae of young oysters, as well as the older ones in their shells.

The Oyster seems to have no defense against this multitude of predators except its shell, and that doesn’t always defend it. As a species, the Oyster only survives because of its amazing fecundity. It is the marvelous fruitfulness of the Oyster that guarantees that there will always be young Oysters settling down and growing to maturity in places away from the cultivated beds of commercial oystermen.

This was one of those, a natural oyster reef. While aquaculture operations keep the species alive and nourish coastal economies, and provide exquisite food for dinner plates, they don’t provide the reefs that buffer shores from erosion and storm surges, which are increasing with the changing climate. Here were wild oysters still living, thank Aphrodite, who was later called Venus by the Romans: goddess of no less than love.

One of the students, an environmental thought and practice major named Isabella Hardy, who went by Belle, with long blonde hair knotted onto the top of her head and pink-tinted sunglasses perched on the end of her nose, came over to offer me her field recording set to borrow for a few minutes. She walked away and went to crouch beside a tidal pool, peering in. I clicked on the recorder and put the headphones on, their padding snug and cushy against my ears, and the world around me faded out. I found a shallow pool within the reef and plunked the hydrophone down. As soon as it sank into the water, my ears were overwhelmed with noise, a cacophony of snapping against my tympana. It sounded like hot oil jumping on a cast-iron skillet, or a basket of fish crackling in a deep fryer. Knuckles cracking before a fight, arthritic knee-joints taking a flight of steps.

With the noise, my vision shifted. I began to see drops of water pinging outward from the living oysters and onto the still surface of the pool. I saw marine snails sliding over the reef, and other animals with shells on their backs and little claws, or masses of flesh, protruding. Crabs scuttled everywhere. The reef was hopping, a hub of activity at the edge of the land and the wide ocean.

“It’s ironic, because our own listening disturbs things and makes noise.”

Oysters had at first seemed inert and mute. Their living flesh stays hidden away in the shell. The bed of skeletons, like a boneyard, had seemed bleak and lifeless. The hollow concavity of the shells emptied of flesh. With the hydrophone resting in the pool, all the popping in my ears gave me the feeling of being tickled. Now I heard the bustling fruitfulness of the animals. Flesh that had desires. Flesh that was hungry, like ours.

I would learn that the pops and pings were the sound of the oysters metabolizing—for an oyster has a mouth, an esophagus, kidneys, a digestive tract, a rectum. They suck in water and pass it through a dorsal and ventral chamber in order to cull its nutritive particles. A single oyster can filter around 26 gallons per day. As they eat, they filter the water and make it clean. More clear for sunlight to pass through and be absorbed by seagrasses and plankton, increasing the abundance of life in the marine system.

“The sound you heard isn’t just oysters,” Burtner told me later. “The composite of what makes up that sound is complicated. You also heard the animals that make their home on the reef the oysters built. So I don’t think just of oysters when I listen to that sound. I think of community.”

Oysters are ecosystem engineers, their reefs supporting diverse and vibrant fisheries. A review of research on oyster reefs in the northern Gulf of Mexico described them harboring large-bodied fish at densities of six per square meter; smaller fish and crustaceans at up to 20 per square meter; and even smaller creatures at densities in the hundreds and low thousands.5 As many as 52 species of fish, crustaceans, and other small invertebrates could be found on an individual reef. Atlantic coast oyster reefs can harbor more than 300 species. Austin Humphries, a biologist at the University of Rhode Island and a co-author of that review, says that while coral reefs house the most diverse marine ecosystems, oyster reefs often provide the most diverse habitats on temperate, subtropical coasts. Oyster reefs are the coral reefs of bays and estuaries, and of tidal rivers.

After a few minutes, I returned Hardy’s field recording set to her. The headphones amplified the sound of the oyster reef while they also made me feel alienated from my surroundings. I quickly noticed that I could hear much of the snapping without the help of the machine. By amplifying the noise and concentrating it in my ears, the headphones had helped to tune my listening, a useful technology. Now I realized what I could hear without them.

I heard life arising together, the collaboration of reef-building across species. No man is an island, as no oyster is. The 0.3 percent of wild oysters who thrived there now did so because people made a sanctuary for them. They accomplished that in large part by joining together and raising their voices. In the early 1970s, the U.S. Navy finally gave up its longtime plan to turn one of the barrier islands into a bombing range after coastal communities loudly opposed it; voices that are united can be amplified and heard, even by the forces that intend to silence them.

Soundscapes of restoration will have to include human voices, too.

Starting in the 1990s, The Nature Conservancy and its partners, including government agencies—NOAA, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission—and hundreds of local volunteers, worked to restore these reefs. To build new substrate they dropped bags of empty oyster and clam shells from restaurants; they installed chunks of granite at tributary mouths and built “oyster castles” of concrete. On these substrates, drifting oyster larvae from the tiny percentage of remaining wild oysters took hold, forming new reefs upon which yet more oysters grew as they matured. Drifting through the estuary with the class, we saw new oysters growing on a castle.

When researchers compared the restored reefs with those that accreted naturally, they found that the biomass of the former matched the latter within six years.6 The restored reefs quickly recovered the ability to filter water and buffer the shoreline. “Restoration can catalyze rapid recovery of imperiled coastal foundation species, reclaim lost community interactions, and help reverse decades of degradation,” concluded the researchers.

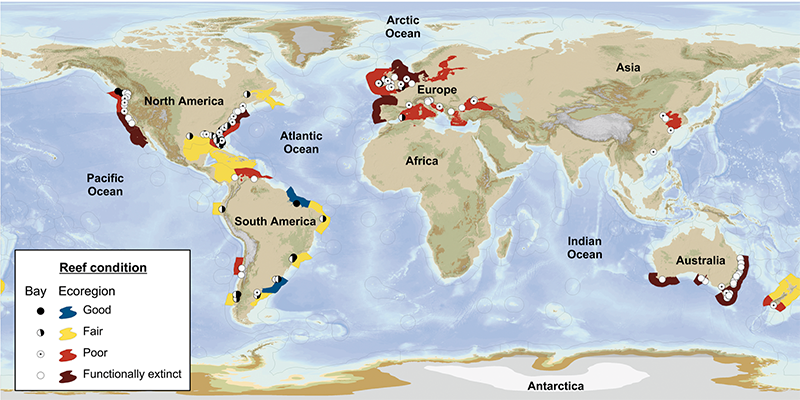

More than 500 acres of oyster reef, an area bigger than Washington, D.C.’s National Mall, have now been restored, making it the largest oyster restoration in the world and hinting at what is possible. Though the scientific name of these oysters, Crassostrea virginica, speaks to their colonial history and importance in the Chesapeake Bay, they are found from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Yucatan Peninsula. Oyster reefs were obliterated in the past few centuries all along this range, with the remnants often reduced to “functional extinction”: present, but no longer performing their ecological roles. Perhaps other oyster reefs can be restored as they have been here.

Where people once gathered, listening to the rhythms of the tides, celebrating their lives on land at the edge of chaos, they might gather again on the shores of our rising seas to create soundscapes of restoration. They might make new sanctuaries for oysters to huddle like congregations of ears—listening, if they could listen, to people who care for them. Sensing, with their suite of subtle senses, the changing world around them.

I held my phone near the reef and used my voice memo app to record it, like I do when interviewing a human source. Later, listening back, I heard the oysters clicking, the waves crashing softly, wind scooting across the mic, and students talking and laughing nearby. It wasn’t a “good” recording, by the standards of nature recordists. It was sullied, ruined by the voices, and I trashed it.

The students and I worked to help Burtner stake a recording device into the substrate, steadying it until it sat upright above the water. The recordings would be archived for long-term ecological research, and he might also use them for his own compositions: Burtner is now at work on an album called Soundscapes of Restoration. “I like to set up the equipment and then get out of the listening equation,” he told me. “It’s ironic, because our own listening disturbs things and makes noise.”

Sometimes human voices ruin nature recordings. And yet, in a sense, soundscapes of restoration will have to include human voices, too.

Burtner gave the students time to be there and wander along the reef and on the island’s margins. The oysters popped, shorebirds wheeted, the wind fluttered on my eardrums, played with my hair and tangled it.

The students and I gathered to listen together. “They sound like tongues clicking,” said one. Like new words and stories, I imagined.

Finally we departed, the boat sliding past the recording device at the edge of Wreck Island where the high tide would wash in and cover the reef. We left a device overnight to listen without us, to make recordings without our voices in them. ![]()

Lead photo by Holly Hayworth

References

1. Classen, C. Shell and shell-bearing sites in the Carolinas: Some observations. Archaeology of Eastern North America 45, 73-84 (2017).

2. Wilberg, M.J., Livings, M.E., Barkman, J.S., Morris, B.T., & Robinson, J.M. Overfishing, disease, habitat loss, and potential extirpation of oysters in upper Chesapeake Bay. Marine Ecology Progress Series 436, 131-144 (2011).

3. Ross, A. The record effect. The New Yorker (2005).

4. White, D. The Volgenau Virginia Coast reserve story. The Nature Conservancy (2021).

5. La Peyre, M., Marshall, D.A., Miller, L.S., & Humphries, A.T. Oyster reefs in Northern Gulf of Mexico estuaries harbor diverse fish and decapod crustacean assemblages: A meta-synthesis. Frontiers in Marine Science 6 (2019).

6. Smith, R.S., Lusk, B., & Castorani, M.C.N. Restored oyster reefs match multiple functions of natural reefs within a decade. Conservation Letters15, e12883 (2022).