Merpeople’s hybridity has helped them maintain a presence in both scientific and mythological camps. In many people’s minds, mermaids and mermen remain mythical creatures more suitable for bedtime stories than scientific tracts. Yet for others merpeople symbolize the outer limits of our scientific and mythological investigations.

Just as the evolution of science has not done away with lingering notions of wonder and myth, so too has our innate need to push boundaries of knowledge led humanity into strange—often mind-blowing—frontiers of research and self-reflection. Humanity’s interaction with merpeople demonstrates our ongoing need for discovery as much as our attempts at regulation and classification. Like the hybrid monstrosities with which humankind has always grappled, humanity maintains a tenuous balance between wonder and order, civilization and savagery.

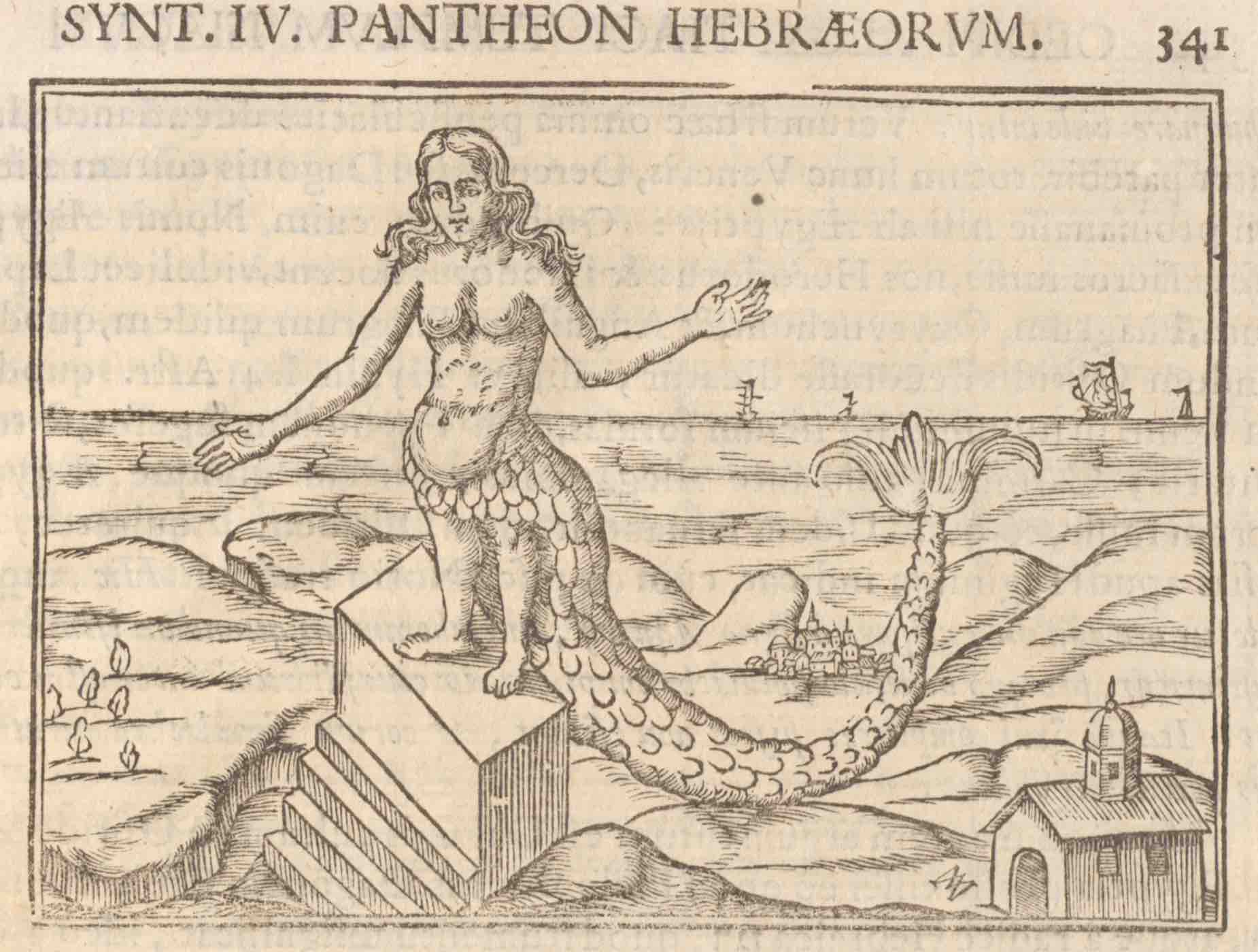

Perhaps nowhere is this fragile equilibrium more obvious than in the early Christian Church’s myriad representations of mermaids and tritons. Murky ideologies of mermaids and mermen originated in ancient gods and goddesses of the sea; although mermaids now rule as the more popular of the two, merpeople’s predominance began with mermen. The Babylonians had their fish-god Oannes dating back to 5,000 BCE, while the Philistines, Assyrians and Israelites created the ‘female prototype’ for the mermaid with Atargatis, a fertility goddess who was the female counterpart to Oannes. Importantly, Atargatis also symbolized the danger of love and lust, an association which Christians would later embrace wholeheartedly.

A spate of pagan representations of merpeople followed Oannes and Atargatis, ranging from Greek and Roman depictions of Aphrodite and Venus, respectively, to Pliny the Elder’s descriptions of mysterious human-fish sea creatures in 80 CE, to the Greeks’ incorporation of Triton (the origin for the merman) and his wife Amphitrite, to Odysseus’ fateful encounter with the harpies (airborne daughters of sea-goddesses) on his famous voyage. Oddly, harpies and the Greek ‘Scylla’—hybrid monstrosities with little resemblance to half-fish, half-women mermaids—would ultimately spawn modern interpretations of mermaids. Over time, artists and writers took the helm in transforming the monstrous representations of Scylla and Homer’s harpies into our modern interpretations of mermaids, replete with sexual overtones, siren songs and the overtly feminine (often naked) form. Thus, while mermen found their origins in a Greek god, mermaids largely originated from hideous beasts who only intended to bring man to destruction through his own lust for sex and power. As would be demonstrated by the early Christian Church, such connotations of sex, lust and power were no coincidence.

Beginning in the third to fifth centuries CE, Church leaders simultaneously adopted, transformed and harnessed ancient pagan symbols of merpeople to assert notions of piety, faith and self- control. Although mermen had long been associated with rape and violence, the early Christian Church was on a mission to dethrone femininity, and had little use for these male monstrosities. Rather, churchmen hoped to transform notions of the Homerian harpy to fit their own means, and in doing so adopted more sexual connotations and imagery in their representations of mermaids.

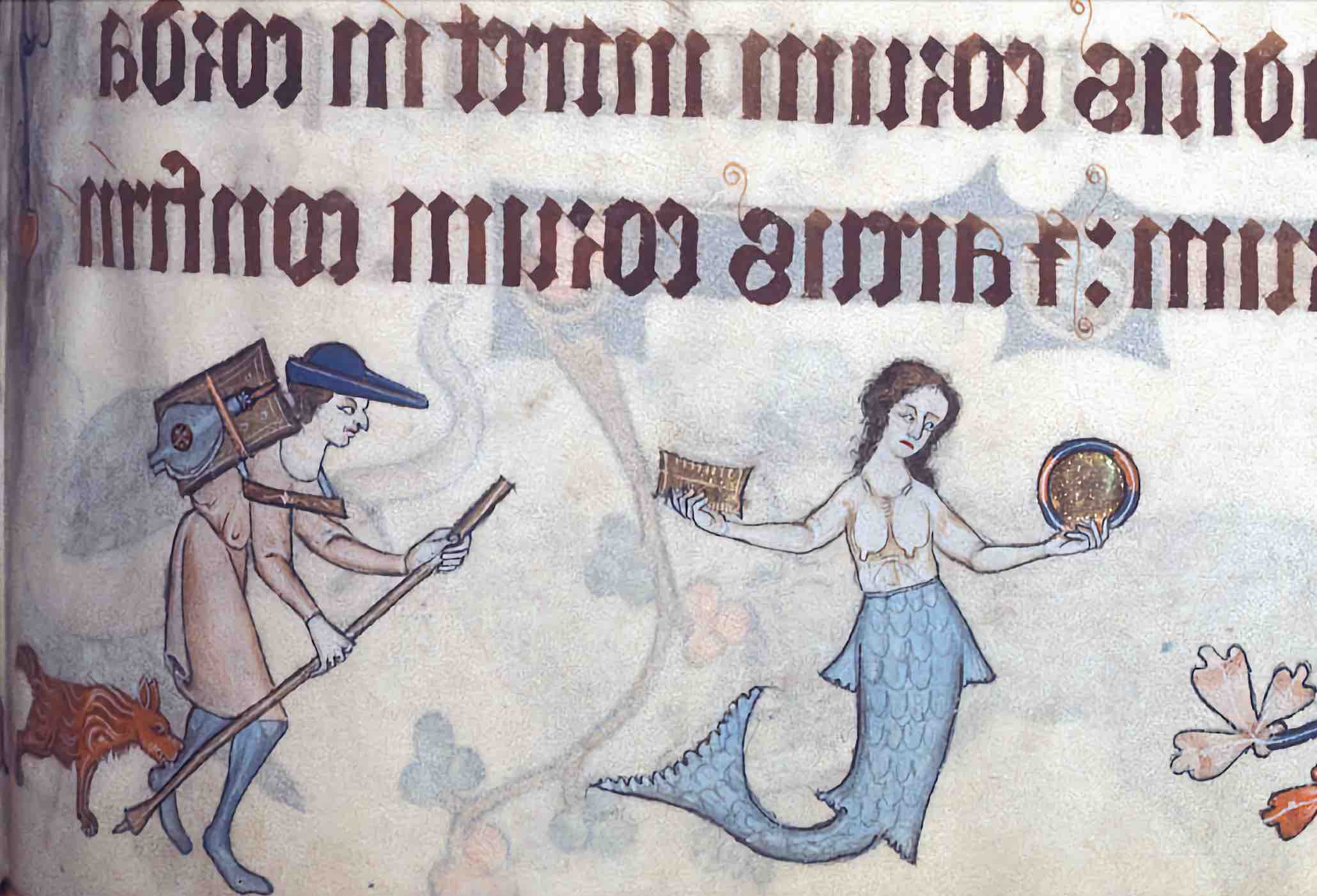

Physical representations of merpeople were critical to this process. Our modern conception of the mermaid stems directly from early churchmen’s depictions of these mysterious creatures. Traditionally shown as human females above the waist, with long, flowing hair and bare breasts, a mirror in one hand and a comb in the other, these half-women, half-fish served as ideal symbols of wonder and danger for Church leaders. Beyond utilizing such ‘monsters’ to demonstrate God’s ability to ‘alter his own laws of nature’, churchmen especially adopted these pagan creatures in an effort to depreciate the feminine—hence the overtly sexual representation of mermaids in church carvings, bestiaries, illuminated texts and artwork. Nakedness—especially as a vehicle for sexual lust—was rare in early Christian and medieval art. Thus, as topless women (who also boasted scaly fish-tails), mermaids would have harnessed a shock factor through image alone.

Church leaders simultaneously adopted, transformed and harnessed ancient pagan symbols of merpeople.

Oftentimes, in fact, church sculptors portrayed mermaids ‘spreading’ their tails apart, thereby exposing their reproductive area—or vesica piscis (Latin for ‘vessel of the fish’)—in graphic detail. A mermaid’s accessories also revealed deeper symbolism, with her mirror and comb representing vanity (not to mention the duality of one’s soul outside the body) and her flowing hair signifying fertility. Sometimes, mermaids would hold a fish instead of a comb, which probably further symbolized her link to the fish as an early symbol of Christianity. By the medieval period (the fifth to fifteenth centuries CE), churchgoers throughout Europe worshipped in spaces decorated with overtly sexualized mermaid imagery. Church leaders, meanwhile, cultivated an intimate knowledge of these strange creatures through myriad texts, art and sculpture. Such ubiquity helped to facilitate general acceptance of, and belief in, mermaids.

In symbolism used by the early Christian Church, mermen were not as popular as mermaids. When mermen occasionally appeared in church carvings, they were almost always paired with mermaids. This representation correlated with early Christian and medieval imagery—especially cultivated in illuminated texts and bestiaries—which generally depicted mermen as partners of mermaids. Mermaids were much more likely to appear alone than were mermen. In contrast to the beautiful (and dangerous) female form of the mermaid, moreover, authors and illustrators represented mermen either as ugly creatures intended to oppose the mermaid’s striking femininity and sexuality, or as symbolic of Christian piety.

Ultimately, mermaids—hybrid creatures of myth and lore—symbolized the early Christian Church’s willingness to hybridize itself (that is, embrace a mix of pagan and Christian belief systems) in its larger attempts to cultivate the largest following possible. Here, the Christian Church deliberately adopted and adapted pagan symbols in its holy spaces, thereby bridging the gap between the supposedly ‘savage’ and the civilized; the past and the present. And it largely worked, as Christian doctrine steadily decentered symbols of the sacred feminine by the medieval period. However, such efforts had unexpected side effects, as by utilizing these hybrid monstrosities to support religious tenets the Christian Church legitimatized such creatures, which in turn created the foundation for belief and acceptance for generations to come.

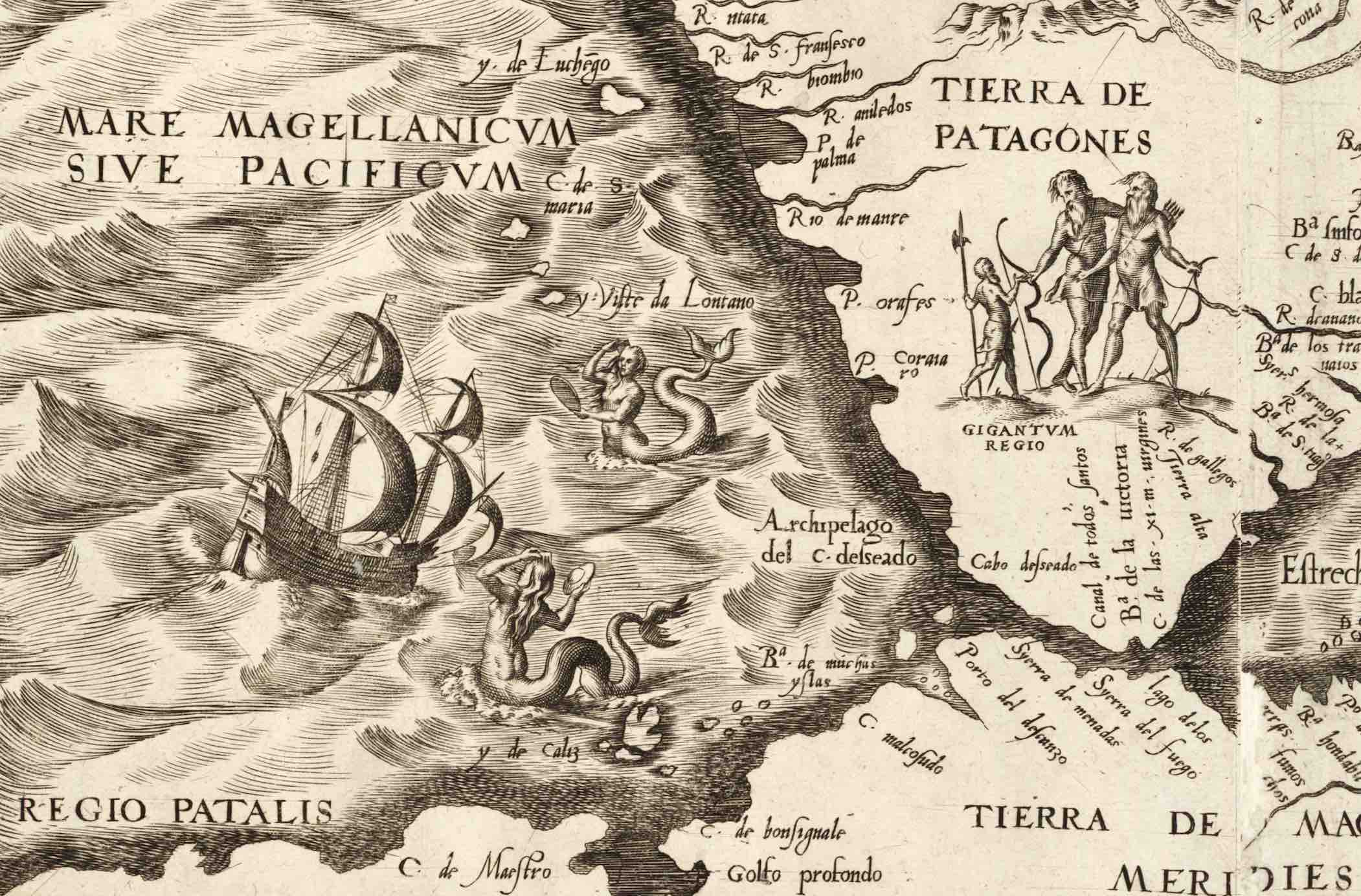

The ‘Age of Discovery’ (roughly 1500 to 1700 CE) only solidified Westerners’ long-standing beliefs and cultural traditions surrounding merpeople. By 1492 Westerners had long lived in a world of merpeople: especially in wealthy, sea-faring societies like Venice or Genoa, merpeople became almost ubiquitous mainstays of art, ranging from tombs to tomes, sculptures to tableware. Unsurprisingly, by the time Westerners pushed further east and west into what were, for them, uncharted territories, they fully expected to find mermaids and tritons. They had, after all, lived their lives surrounded by these mysterious creatures. Importantly, before the ‘Age of Discovery’, Europeans placed Jerusalem in the centre of the globe in terms of religious tradition. The further one got from Jerusalem, the stranger and more dangerous the world became. If merpeople lived anywhere, many early modern Westerners believed, it must be at the ends of the Earth, where monstrosities and curiosities thrived.

The ‘Age of Discovery’ only solidified Westerners’ long-standing beliefs surrounding merpeople.

As Westerners heightened their interactions with the Pacific and Atlantic worlds in a search for monetary, religious and imperial power, recorded sightings of merpeople multiplied exponentially. The Atlantic Ocean and its ‘New World’ shores were especially rife with such interactions, as famed explorers integrated merpeople into their understandings of strange—and potentially lucrative—environments. Yet, where in the medieval period interactions with mermaids and tritons usually uncovered a deeper lesson over lust, vanity or religion, early modern explorers transformed such contact beyond manifestations of the Christian creed and instead began to reflect in their ‘mer-sightings’ emerging notions of exploration, growth and national prowess. Each Western country had its own stories of merpeople, and in each of these interactions the nation tried to assert its understanding of the globe. Monstrosities abounded in the New World, and Europeans were intent on uncovering their secrets. This was a period of legitimization for merpeople.

As sightings proliferated and European Christians steadily colonized the Americas, Western mapmakers began in earnest to chart these strange new worlds. Of course, such cartographic creations were as much about Europe’s effort to position itself as a world power as they were about accurately recreating the New World topography. These maps were also, importantly, intended to demonstrate the exotic opportunity of the world, while also shrinking its size to suit Europeans’ imperialist efforts. Therefore ‘strange’ or ‘foreign’ lands like the Americas and the ‘Far East’ were often depicted with merpeople in their surrounding seas.This was no mistake, nor can it be boiled down to a temporary flight of fancy. Mapmakers intentionally included merpeople in their evolving representations of the world in an effort to demonstrate the strange quality of these environs, while also signaling to viewers the possibility of interactions with such creatures. Such representations only further primed explorers to find mermaids that, in turn, only further encouraged mapmakers to include them in their illustrations, and so on.

In many ways, then, the ‘Age of Discovery’ was also a new age of interaction with merpeople. Such heightened instances of ‘strange facts’ created an interesting confluence of science and wonder during the Enlightenment period (roughly 1700 to 1800) in Western Europe. Many of the smartest men in the eighteenth-century Western world expended consider- able time and effort searching for, drawing and analyzing merpeople. Their efforts reveal that the ‘Enlightenment’ was not simply a time of rationalism and science, when Western thinkers threw off the supposedly mythological, wondrous cloak of their forebears. Instead, it was a period of massive change and expansion when European thinkers were perhaps more open to the wonders of the natural world than ever before; they simply had more scientific, theoretical and analytical tools at their disposal.

By the end of the eighteenth century, gentlemen philosophers had drawn numerous specimens of merpeople ‘from life,’ collected mermaid hands in their cabinets of curiosities, funded global voyages to capture merpeople and penned numerous analytical pieces on merpeople’s existence, not to mention their anatomy and lifestyles. Ultimately, Enlightenment thinkers’ efforts to dis- cover mermaids and tritons demonstrated their ongoing hope to gain a deeper understanding of the world and humanity’s place in it.

Even with this proliferation of the study of merpeople, many European philosophers, scientists and anatomists remained skeptical of the existence of merpeople. Nevertheless, by the early nineteenth century, ‘mer-mania’ had reached fever pitch. This explosion of interest was especially revealed through newspapers. A nineteenth-century Westerner would have encountered a sighting, specimen, show or study of a merperson in his local newspaper at least once a month during the first half of the nineteenth century; Western readers were primed to finally figure out the mystery of merpeople. Industrialists pushed into hitherto underexplored regions, scientists classified and ordered the world with increasingly fine precision, and communication expanded to new heights. Newspaper publishers, of course, were more than happy to satisfy this insatiable thirst, printing stories of merpeople with little credulity and fueling underlying belief in these creatures. Purveyors like the English Captain Samuel Barrett Eades only added to this mania with his physical specimen of a supposed mermaid caught in the East Indies (it was really just a fake constructed by Japanese craftsmen for the Western market). Londoners flocked to see Eades’s mermaid in 1822, and a flurry of copies followed his example. Newspapers could not get enough of it, printing daily advertisements, studies, reviews and think-pieces on these mysterious creatures. Perhaps the mystery had finally been solved?

In a word, no. P. T. Barnum, the famous American showman known worldwide for his lavish (usually misleading) exploits, both crested and destroyed Westerners’ belief in merpeople in 1842 with his infamous ‘Feejee Mermaid’ (which was actually just Eades’s mermaid repurposed for American audiences). A slew of scientific studies, public viewings and advertisements throughout North America made Barnum’s mermaid the most popular instance of human interaction with merpeople ever. Yet it also drew the curtain back from the mysteries of merpeople, thereby revealing these long-debated creatures as little more than ‘humbuggery’. Combined with the development of scientific classification and evolutionary studies, the revelation of Barnum’s fakery largely dis- integrated multi-century belief in mermaids and tritons as living creatures. Although mer-folklore lived on in the Western world, such stories descended into little more than flights of fancy, with Barnum—and the mythical mermaid—becoming a punchline more than a point of speculation.

Despite scientists’ efforts to destroy popular—and academic—perceptions of merpeople’s reality, nineteenth-century scholarly investigations remained wedded to these perplexing creatures. Whether key thinkers of the day were arguing that mermaids and tritons were actually seals, manatees and dugongs, or debating the efficacy of Linnaeus’ classification system and Darwin’s theory of evolution, merpeople remained central in ongoing scientific analysis. By the end of the nineteenth century, Western historians began to produce volumes dedicated to merpeople’s long history, while aquariums and zoos advertised manatees and dugongs as ‘real mermaids’ (they are still categorized under the order ‘Sirenia’). Of course, this overlap of science and myth was nothing new for mermaids and tritons. Since the third century CE, Westerners embraced merpeople for their very ability to blur these lines. At the turn of the century, Westerners had simply altered the parameters for such murky intersections of science and wonder, past and present.

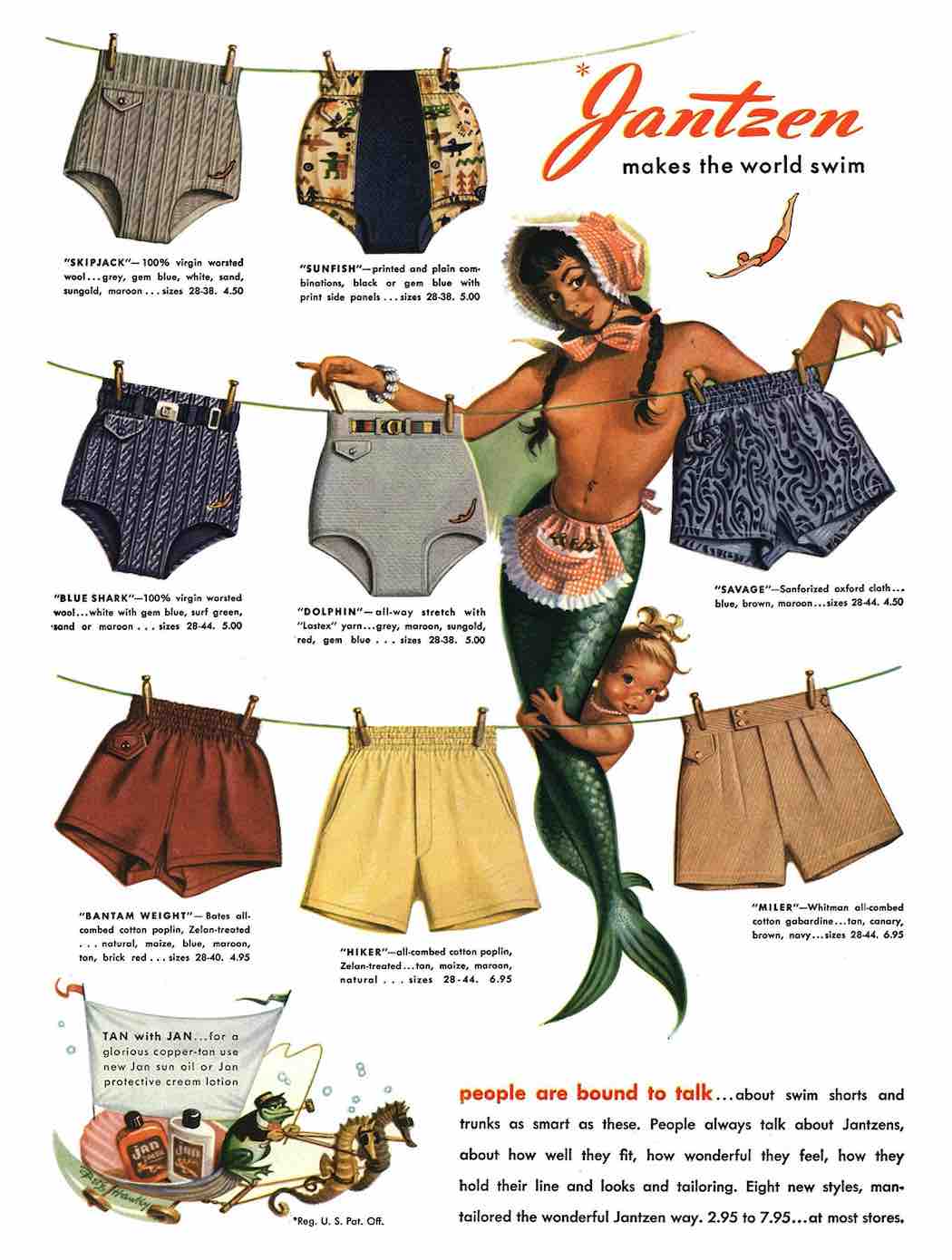

Nevertheless, by the early twentieth century, belief in the existence of merpeople had largely dissipated in Western culture. But this is not to say that mermaids and tritons became irrelevant. On the contrary, merpeople—especially the mermaid—became a critical symbol of sex, media, capitalism and profit. As Westerners transitioned into an era of disbelief, interestingly (and somewhat ironically) they vaulted mermaids to the highest popularity these sensuous sirens have ever enjoyed.

Mermaids’ commercial popularity relied upon their long association with sex, lust and wonder. Where the early and medieval Church had utilized such characteristics to warn against indulging desires, twentieth-century media embraced mermaids’ sexual nature for marketing purposes. Especially after the Second World War—a time when America’s capitalistic future seemed brighter than ever—advertisers, film-makers, showmen and artists seized upon mermaids as poster-creatures of profit. The American media wanted the sex and danger that the Christian Church had created so as to damn.

Reprinted with permission from Merpeople: A Human History by Vaughn Scribner, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © Vaughn Scribner 2020. All rights reserved.

Use the code PR20MER for 20% off Merpeople: A Human History.

Lead image: ArthurRackham, ‘Clerk Colvill and the Mermaid’, illustration from Some British Ballads (1919).