Imagine the South China Sea: not as balmy waters dotted by palm-fringed islands, but covered in a sheet of ice. The deeper waters have cooled, too—not like the surface, but enough to alter the currrents that flow between Earth’s equator and its southern pole. In the ensuing ecological cataclysm, humans depend on seaweed for their survival.

That’s not the usual picture of post-nuclear apocalypse. Most popular fictions of the subject have focused on terrestrial impacts, and scientific research has shared that tendency. But factor in the ocean, suggest researchers whose simulations did just that, and humanity is looking less at a nuclear winter than what they call “a Nuclear Little Ice Age.”

One of those researchers is Owen Toon, a geophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder. In the 1980s, Toon worked alongside Carl Sagan as part of the first generation of environmental scientists to model the planetary effects of nuclear warfare. The early climate models they used showed that multiple large detonations could generate enough smoke to wrap Earth in a veil so thick it would block out the sun, a scenario they famously dubbed “nuclear winter.”1

Outcomes such as unforeseen extinctions and shifts in migration patterns are almost a given.

Now, using more-advanced climate models to simulate the effects of United States-Russia and India-Pakistan nuclear conflicts, Toon and colleagues, led by the Louisiana State University oceanographer Cheryl S. Harrison, have provided the first detailed look at the impacts of nuclear war on the ocean. Their findings, published last year in the journal AGU Advances, describe a planet transformed even more profoundly than earlier simulations suggested.2

No matter who cracks open their arsenal first, the model begins with smoke. Even at the tame end of their scenarios,3 with the nations using about one-quarter of the 400 to 500 warheads they’re expected to accumulate within the next several years, an India-Pakistan nuclear war would generate nearly 20 times the amount of smoke produced by the catastrophic Australian bushfires of 2019 and 2020. Those released a whopping 0.9 teragrams (Tg), or 900,000 tons, of carbon soot—the largest recorded amount to ever enter the atmosphere. At its worst, with charred cities pumping hot clouds into the sky, a conflict between the two countries could produce almost 47 Tg of smoke. And were the U.S. and Russia to engage, deploying roughly 100 bombs of equivalent power to the one dropped on Hiroshima, the estimated output would be a nearly incomprehensible 150 Tg of soot.4

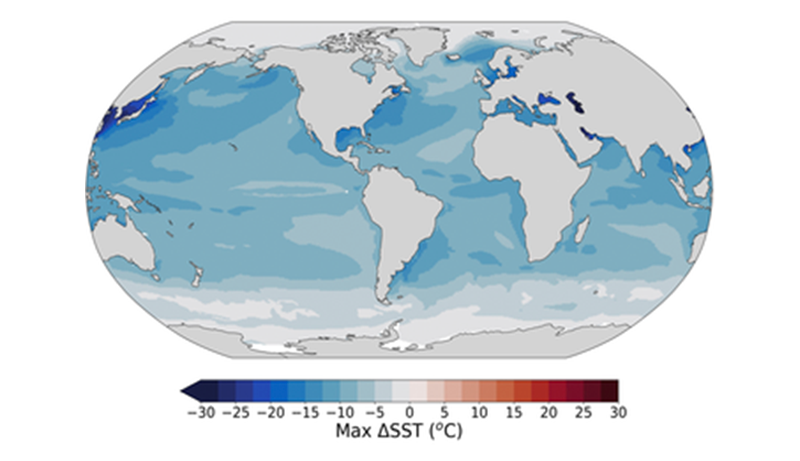

In all cases, the smoke spreads fast. Within a week or two, a layer of smoke hovers above the entire planet. There’s less sunlight; everything starts to get just a tad colder. In the U.S.-Russia scenario, Earth cools an average of 7 degrees Celsius in just a few months. The global temperature decrease persists for at least a decade. Because water retains its heat longer than air, the ocean’s surface doesn’t reach its coolest until three to four years after detonations end, when ocean surface temperatures fall by an average of 6 degrees Celsius worldwide.

The climate models paint a scenario that is roughly equivalent to a small asteroid hitting Earth. The one that eradicated the dinosaurs had many of the same effects, albeit to a larger degree. And, much like that infamous asteroid, a nuclear war causes ice to expand across much of Earth’s surface. Arctic sea ice doubles in thickness, and portions of the South China Sea and the Atlantic Ocean—predicted to cool by about 25 and 10 degrees Celsius respectively—could freeze as well.

Radical as those changes are, it’s what happens at depth that alters the ocean forever. With such dramatic cooling at the surface, the comparatively warmer waters of the deep begin to rise and mix with the layers above, disrupting the narrow temperature ranges and familiar current patterns that now sustain its life.

Tyler Rohr, a biogeochemist at the Australian Antarctic Partnership Program, was tasked with deducing what such extreme deep-sea churning and cooling means for marine life. He studies phytoplankton, the microscopic photosynthesizing organisms who are the foundation of oceanic food webs; as skies fill with soot, phytoplankton are immediately deprived of much of the sunlight they need to survive. Their populations fall by 50 percent in the months following the modeled U.S.-Russia conflict, and remain at least 20 percent lower for years. It’s difficult to predict exactly what that would do to marine ecosystems, but Rohr is confident that it would make parts of the ocean unrecognizable.

“Whenever you have a massive climate disturbance, the consequences are large in scale and time,” Rohr says. “There can be these really surprising mechanisms that can cause feedbacks that create unpredictable and unexpected outcomes even decades down the road from the initial disturbance.”

Outcomes such as unforeseen extinctions and shifts in migration patterns are almost a given. Among the predictions that Rohr and colleagues could make is that, 10 years after a worst-case-scenario nuclear war, the ocean would contain 20 percent fewer fish—and that’s without accounting for how declines in terrestrial food sources might lead to increased fishing, a shift they say is likely.

A nuclear war causes ice to expand across much of Earth’s surface.

Some of the researchers involved in the post-apocalyptic ocean study also modeled worldwide food output in the aftermath of a nuclear winter. According to their estimates, which were published last year in the journal Nature, the collapse in global calorie production following an India-Pakistan conflict could lead to 2 billion deaths; for a U.S.-Russia war, the toll swells to 5 billion.5 Facing that kind of nutritional scarcity, even a depauperate ocean would be a vital food source.

There is one food, however, that may be bolstered by nuclear cooling: seaweed. In certain tropical and subtropical areas, such as parts of the Sargasso Sea, the researchers found that seaweed could continue to flourish, even in these dire scenarios. Seaweed might even help sustain humanity while terrestrial food webs recovered and the ocean slowly came back to life.6

Ten years after the war a long period of semidarkness finally gives way to bright, sunlit days that more closely resemble a pre-detonation world. Meanwhile the cooling-induced upwelling of deep-sea waters has delivered a vast supply of the nutrients that phytoplankton consume. Add sunshine, and an explosion of life at the smallest level ensues.

By two decades after war, the ocean’s net primary productivity—the sum total of its biomass—settles into a new state, around 6 percent higher than pre-war levels. This bounty is not evenly distributed, though. Regional variation means that some areas won’t see much new life for thousands of years or more.

Toon and colleagues describe this as the ocean’s “recovery,” which is accurate in that the ocean’s productivity will, by some metrics, return to pre-war levels. But by the word’s other definition, the regaining of things lost, oceanic recovery after nuclear war is impossible.

Because of their place at the top of food chains, larger aquatic species are the most likely to be lost during a nuclear war’s immediate aquatic aftermath—and though a horde of phytoplankton may have the same biomass as a blue whale, it lacks just about everything else that makes the ocean’s biggest creature special.

A recovered ocean is still an unrecognizable ocean. And while evolution would yield new marine species, that would take exponentially more years than the simple recovery of biomass. There’s just no way to model something like that. ![]()

Lead image: Sergey Nivens / Shutterstock

References

1. Turco, R.P., Toon, O.B., Ackerman, T.P., Pollack, J.B., & Sagan, C. Nuclear winter: Global consequences of multiple nuclear explosions. Science 222, 1283-1292 (1983).

2. Harrison, C.S., et al. A new ocean state after nuclear war. AGU Advances 3, e2021AV000610 (2022).

3. Toon, O.B., et al. Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe. Science Advances 5 (2019).

4. Coupe, J., Bardeen, C.G., Robock, A., & Toon, O.B. Nuclear winter responses to nuclear war between the United States and Russia in the whole atmosphere community climate model version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies model. JGR Atmospheres 124, 8522-8543 (2019).

5. Xia, L., et al. Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection. Nature Food 3, 586-596 (2022).

6. Yong, W.T.L., Thien, V.Y., Rupert, R., & Rodrigues, K.F. Seaweed: A potential climate change solution. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 159, 112222 (2022).