Science has been missing something. Something central to its very existence, and yet somehow just out of view. It is written out of papers, shooed away, shoved into laboratory closets. And yet, it’s always there, behind the scenes, making science possible.

“Lived experience is both the point of departure and the point of return for science,” astrophysicist Adam Frank, physicist Marcelo Gleiser, and philosopher Evan Thompson write in their new book, The Blind Spot: Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience. We use the fruits of our experience—our perceptions and observations—to create models of the world, but then turn around and treat our experience as somehow less real than the models. Forgetting where our science comes from, we find ourselves wondering how anything like experience can exist at all.

The authors trace this “amnesia of experience” to a philosophical shift by the Greeks—later cemented in the 17th century with the rise of classical physics—which split reality in two: inner and outer, mind and body, subjective and objective. This rupture allowed science to make enormous progress; by dealing only with the second half, science could model the world as simple matter in motion, a mechanistic view that birthed industrialization, technology, modern life.

Everything we do starts with our experience of being in the world.

That left the first half hanging—so scientists chalked it up to illusion or epiphenomenon; they tucked it away into our collective blind spot.

In vision, it’s what’s in the blind spot (the optic nerve) that allows us to see. And the same, the authors argue, is true in science: It’s experience that allows science to function. It’s a fact we better remember, they urge, before it’s too late.

Today’s major conceptual difficulties—the unruly multiverse, the hard problem of consciousness—as well as existential dangers—artificial intelligence, climate change—are, the authors argue, the result of ignoring the blind spot for too long.

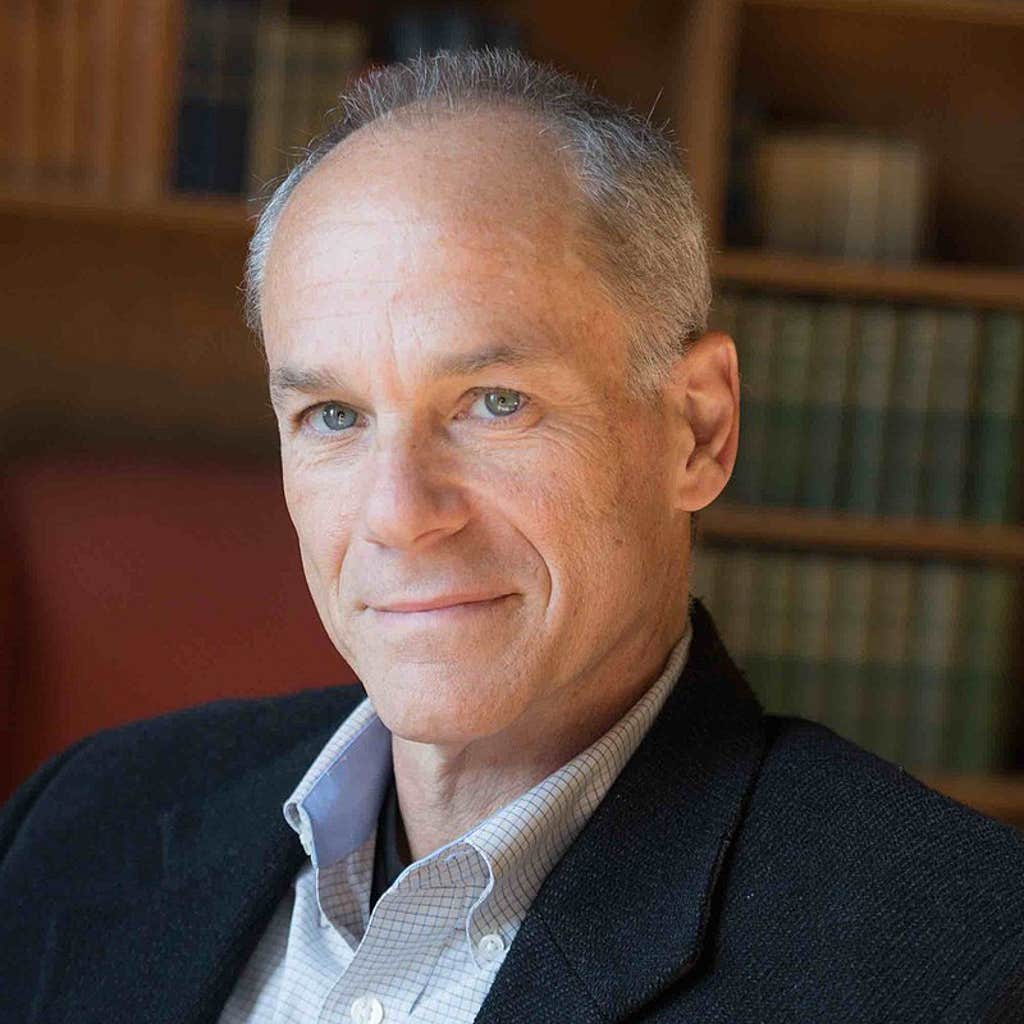

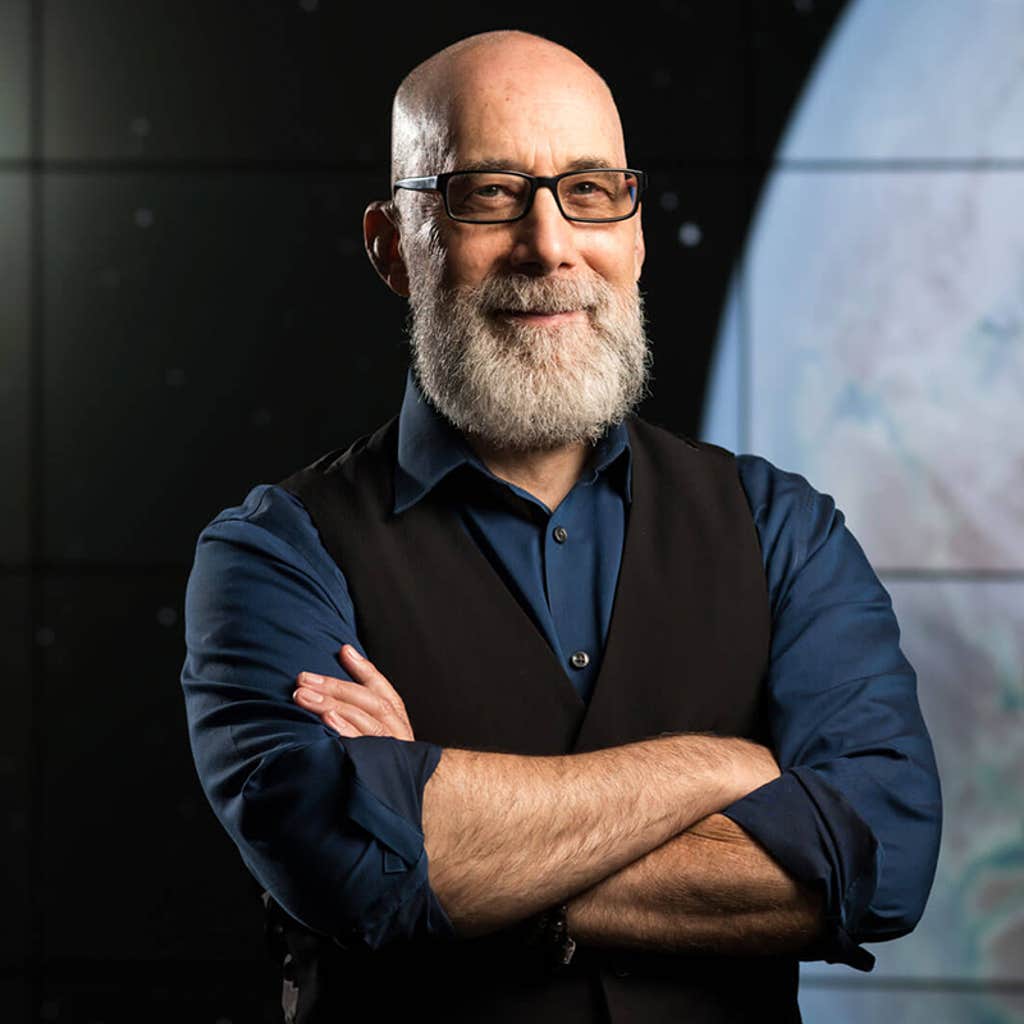

The Blind Spot is a controversial book—a manifesto, really—one that seeks to overturn centuries-old philosophical assumptions that are commonly mistaken for science itself. I spoke with all three authors together over Zoom: Frank, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Rochester; Gleiser, director of the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Engagement at Dartmouth College; and Thompson, a philosophy professor at the University of British Columbia. We talked about the social nature of consciousness, the impossibility of Boltzmann brains, and the trouble with taking a God’s-eye view of the universe.

What is the blind spot?

Marcelo Gleiser: Modern science began by looking at how things moved in the skies, and that was easy to do through a mechanistic, objective way of thinking about the world. That success gave us excessive confidence that we can take this God’s-eye vision of the world, rationalize everything, and forget about the most fundamental thing of all: that everything we do in life, and in science, starts with our experience of being in the world. When we take ideas too far away from where they originated in experience, we get lost.

Evan Thompson: Take the example of temperature. We start with bodily sensations of hot and cold. Then we progressively abstract and idealize until we arrive at thermodynamics. And there’s nothing wrong with that—that’s essential for the development of science. The problem is when we forget. We substitute mathematical models for the concrete phenomena themselves. The blind spot is that amnesia of experience.

Whether we’re talking about measurements in quantum mechanics, the experience of time and duration, or the investigation of living systems, there’s always an experiential source and motivation that, at the end of the day, has to be readdressed in order for the science to be valid and meaningful.

What goes wrong when we forget about experience and try to take this God’s-eye view of reality?

Adam Frank: We see it with the multiverse. There’s this enormous extrapolation that has already gone into the theory of cosmic inflation. It originally was a great idea, but then it turns out, well, the fields that we wanted for the inflaton—the proposed mechanism behind cosmic inflation—they don’t really work. Then there’s more and more abstraction until the inflaton field isn’t really connected to anything, you’re just making it up. And then that long series of abstractions leads to the conclusion, “oh, there’s got to be an infinite number of unobservable universes!”

By reifying abstractions, you’re getting so far away from the grounding in lived experience that you’re willing to accept ideas that can’t even be validated scientifically.

Marcelo Gleiser: They’re beyond experience.

Adam Frank: You have to return to experience. Especially when you get into trouble like that.

I think when most people hear the word “experience,” they think of something that happens inside of them—inside their heads. But of course that idea of experience—as something totally internal and individualistic—is rooted in the same 17th-century ideas that the blind spot you’re talking about came from. So what I want to ask is: What is experience, where is experience, and who does it belong to?

Evan Thompson: Experience for us is always social and intersubjective—and we criticize views of consciousness that make it impossible to understand experience in that way.

For example, there’s work in the neuroscience of consciousness that leads people to say things like, “reality is a controlled hallucination that arises from a predictive coding model in the brain.” If you take that statement literally and follow its logic through, then the brain you think you’re observing is just content inside the model in the head of some individual, and you have no right to the notion of the physical brain that you’re helping yourselves to. And you can’t account for science as a collective enterprise, because then it would be everybody somehow in their own solipsistic universe managing to communicate outside in predictive coding terms, that just doesn’t make any sense as a theory of how the mind works. It’s another reification.

Experience is something that is shared; it has a history and a culture behind it. And a body for that matter. A living body.

In an infinite universe there is a finite probability of anything—an orchid could appear here next to me.

Adam Frank. A body, right. There was one day at Lindisfarne—the intellectual community that Evan’s father founded, where people went to do really radical thinking—and Gregory Bateson, the cyberneticist, was talking with Jonas Salk. Bateson asked Salk, “Where is your mind?” And Salk, being a good reductionist, pointed to his head and said, “Up here.” And Bateson said, “No, no, no”—and motioned around and between them. And he didn’t mean panpsychism. He meant that mind is the interaction.

I would say the entire biosphere is implicated in your experience, you can’t separate out. There are no brains in vats. There are no Boltzmann brains that magically appear. Experience implicates everything, every aspect of life, the entire history of life. It’s a very different way of thinking. The philosopher William James had this idea of “pure experience.” That’s what we want people to focus on. It’s so close that it’s easy to miss. And in our scientific culture, we’ve pushed it away, but it’s what’s given every day when you wake up.

You mentioned Boltzmann brains—hypothetical free-floating brains that spontaneously appear, complete with all the perceptions and memories needed to trick it into thinking it’s an ordinary observer in an ordinary universe. It seems like a perfect example of every one of these blind spot mistakes being made all at the same time. First you assume that a lone, disembodied brain can have experiences, and then you use the existence of those Boltzmann brains to try to define probabilities in an infinite multiverse—by determining the chances you are most likely a Boltzmann brain.

Adam Frank: I’m sure I’m going to offend somebody, and I apologize, but I wanted to write a paper on Boltzmann brains called, “The Dumbest Idea in Physics.” It assumes that experience can happen in this brain in a vat that just spontaneously appears and then you’re going to use that in some theoretical physics framework to decide which kinds of universes are going to have observers in them … it’s an incredible chain of mistakes.

Marcelo Gleiser: Those mistakes are rooted in the reification of infinity. Infinity is not something that we can ever confirm exists in reality. If you say the universe is infinite in space, how can you know that? You’d have to travel infinitely far away. You could say, “Well, the measurements tell you that the geometry of the universe is close to being flat.” Awesome. But you can’t go beyond “close to.” It could still be a very big sphere.

It’s the same for an infinity of time. People play these games with infinity as if it is something real. In an infinite universe there is a finite probability of you spontaneously generating anything—an orchid could appear here next to me, a Boltzmann brain … I mean, poor Boltzmann. Of all people.

He had enough problems.

Marcelo Gleiser: If I saw a Boltzmann brain materializing somewhere, then okay, I’d say, there is something going on here. But, you know, as Bertrand Russell said, go find a teapot in orbit around the Earth.

Adam Frank: In the constellation of ideas that make up the blind spot, reduction is one of the big ones—but so is the kind of Platonism that replaces mathematics for the actual world. And I think probably Marcelo and I started that way. I mean, I don’t want to speak for you, Marcelo.

Marcelo Gleiser: I was a string theorist!

Adam Frank: We’re lapsed Platonists. I was like, “Oh my God, this is great: Spinoza’s idea that the law of circles is to circles as God is to nature”—I had that Einsteinian vision, I was enraptured by it. But as time went on, I just came to see the lack there.

And just to pick up on Marcelo’s point, it’s not only infinity, it’s infinitesimals, and infinite precision. In physics, we make a lot of arguments using phase space and coarse graining, where the idea that you could have infinite precision plays a role in making these blind spot mistakes.

Evan Thompson: I often read statements like, “The universe is a physically deterministic system, and therefore, there can be no free will; free will is an illusion.” That’s a mistake that comes from substituting a model in which things can be stated to infinite precision for the universe itself, where infinite precision is never possible. These things really affect how people understand themselves as living persons in the world. When people are told, “Science says you don’t have free will,” they revolt against that, naturally. And that gets us into a bad situation of science denial, on one hand, and science triumphalism on the other, both arising out of a blind spot misrepresentation of science.

Adam Frank: It’s not science’s blind spot. It’s a blind spot in the philosophy of science that has been glued onto science. It’s a metaphysics that we’ve been told for 200 years: This is what science says. Science says, “You don’t have free will.” Science says, “You are nothing but a meat computer.” No, it doesn’t. The metaphysics says those things. Science itself is this ongoing, creative, self-reinventing process. And that’s what we’re trying to cleave. We’re really trying to show that distinction.

In your book, you have a quote from Newton where he describes an intelligent, omnipresent being who can apprehend all of infinite space at once. In other words, Newton invoked the perspective of God, standing outside the universe, looking at everything at once, as part of the formulation of classical physics. As physics developed, that literal figure of God dropped out of the story, but physics retained the God’s-eye perspective and transformed it into the very notion of objectivity—which is supposed to be the thing that differentiates science from religion. What an interesting plot twist in the history of science! And it seems like it’s especially relevant still in cosmology, where the universe is treated as a singular object, as if one could comprehend it from the outside. Does getting away from the blind spot require us to think differently about the universe?

Marcelo Gleiser: When we talk about the universe as a “thing,” we have to remember that we are inside that thing—like a fish in a bowl. Our current model has too many holes. I think a lot of them come from our limitations in trying to make sense of something that is much bigger than we are. The cosmic microwave background radiation, for example, does not make sense for scales as big as the universe as a whole. That’s where all the error bars are.

From a mechanistic approach, to have a theory of the universe, you have to have an equation that describes the universe as a whole. That equation needs two things: an objective description of the system and an initial condition. But we can’t have either. So the universe provides a clear way of qualifying what we mean by the ramifications of the blind spot.

It seems like the blind spot has been getting us into worlds of trouble. Is the climate crisis one manifestation?

Marcelo Gleiser: We have to think of the history that brought us here. First, the blind spot in science convinced us that we can objectify the world, that the only value it has is as a pool of resources that we can use to supply the demand that we have in our project of civilization, and that there are no repercussions to our actions.

Second is the ideology of infinite progress, brought by corporate greed, which relies on mechanistic ways of thinking about the world that were part of Enlightenment rationality. It’s the idea that we can rationalize our problems and solve them through science alone. “Oh, we’re messing up? No problem, we’ll just sequester carbon from the atmosphere or plant more trees!” That might help, but it’s not going to solve the problem. For that we need to take a much deeper look at our belonging to the natural world, which is connected to the experience of being alive. We have forgotten our bond to the world, and that’s where Indigenous thinking and ancestrality can help us in ways which are not just materialistic but spiritual to reconnect to nature.

Adam Frank: In the ’90s, there was the whole social constructivist thing about science—which we’re very much against—which was like, “Oh, science is just a plaything for the powerful. It’s just a game with made-up rules.” No—the powerful adopted science because it was powerful. Because you can make better cannons. But the philosophy that went along with science, those in power took that on because it was useful. This “decentralized nature,” this nature that has nothing to do with us, is so deeply implicated in the industrial political economies—whether it’s capitalism, socialism, or communism—that it became the only way to look at it.

Moving forward, to get us out of climate crisis, is going to require us to embrace some of these other perspectives that are coming out of science: network theory, information theory, complex systems—ideas that don’t have blind spot metaphysics glued to them. What’s really required is an entirely new conception of nature.

We’re trained that the third-person view is the only way to talk about the world, that anything else is “woo.”

I’m struck by the way in which all these different concepts—the universe, mind, nature—lean on each other. You almost have to rethink them all simultaneously in order to understand what you’re even talking about.

Evan Thompson: That was one of the things that was very salient in working on this book—that all of these things are densely interconnected. It’s not the kind of book that any one of us could have written. It took thinking together. The experience of writing the book wasn’t in anyone’s head. We all came with different bodies of knowledge, and we were all learning from each other. There was no way that could have come about in a more classical, single-authored way.

We actually need to start thinking more in this way, in terms of relationality networks that include us as agents, as measurers, as abstractors. That’s what it takes to work ourselves out of the blind spot.

Marcelo Gleiser: It’s a mindset, a worldview that we are presenting, and it affects everything we do creatively and in science.

How did the three of you end up working together?

Adam Frank: Marcelo and I had been introduced by someone who knew we had similar views about science and religion. That is, we’re both atheists. But we understood that there was still a problem with, as Marcelo put it, the God’s-eye view, or what I think of as the third-person view.

I was aware of Evan’s work. His dad, the social philosopher William Irwin Thompson was one of my heroes, so that connection meant something to me. For sabbatical, I was at the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Engagement at Dartmouth College, where Marcelo is the director, and I suggested bringing Evan.

So Evan came for a few weeks, and our conversations just exploded. We all got along so well, and we recognized our mutual affinity for trying to work this out. Because it’s very difficult! As scientists and philosophers, we’re trained that this third-person view is the only way to talk about the world, that anything else is “woo.” And so we had to try to maintain the rigor of clear reasoning, while also acknowledging that there is a limit to this third-person view, to what we call the blind spot.

We had these amazing conversations over tea, over dinner. I felt like if we’d all been 17 years old, we would have had the same passion arguing over our favorite bands—or we would have started one. That’s why I still refer to us as “the band.”

I think if it was a band, you wouldn’t be having conversations over tea.

Marcelo Gleiser: Well, there was chalk dust involved. ![]()

Lead image: Marish / Shutterstock