Geniuses, however we define the concept, often evoke particular strong feelings. Many of us develop personal affection for them, defending them from criticism as fiercely as we would friends or family. It’s not enough for them to be brilliant scientists or artists; they must also be admirable people. When those heroes inevitably prove to be flawed people, we rationalize, we ignore, we feel betrayed.

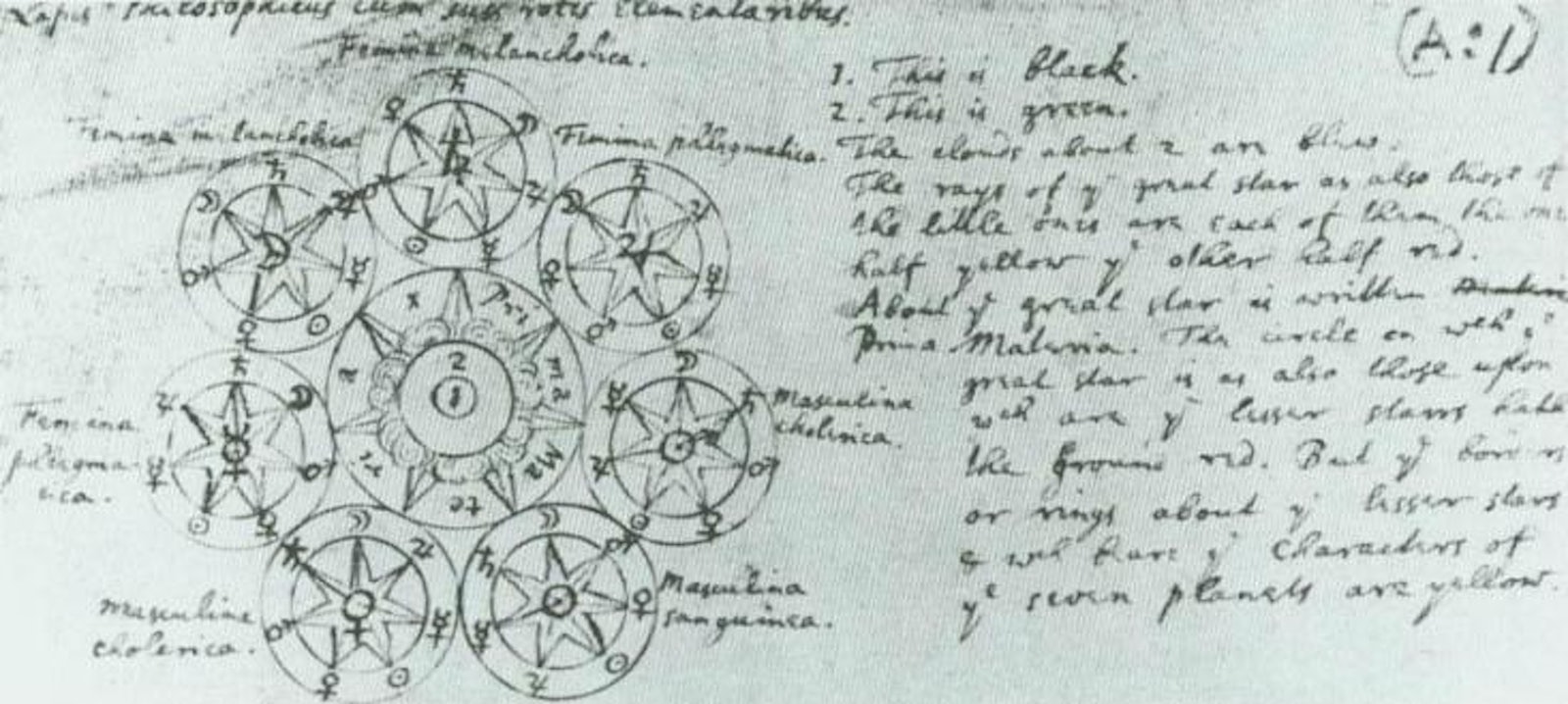

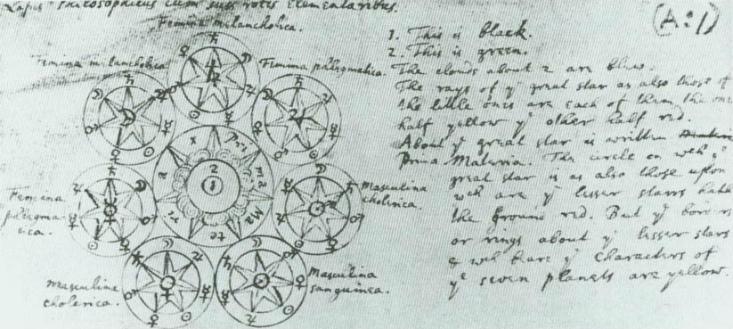

Think, for instance, of the foundational figure in physics, Isaac Newton. His role in establishing calculus and what we call Newtonian mechanics is so important that we ignore or downplay the fact that much of his life work seems misguided and downright weird to modern eyes. Newton considered his alchemical and theological work to be as significant as what we would identify today as science. Even more disturbing to modern sensibilities, he thought of the science and screwy stuff as aspects of a whole, a single system of the world encompassing the knowledge imparted by God to Moses and other people in antiquity.

But if your education was like mine, you didn’t hear that story in class. You might have heard that Newton turned into a crank in his old age, turning to alchemy and numerology late in life after his brilliant early career as a scientist. That’s what I was taught, and repeated the myth myself in the classroom to my own students. (Students, please forgive me.) But it’s wrong: The chronology of Newton’s life and his own writings contradict it.

Newton’s approach was fairly consistent, whatever he worked upon. He was motivated by a strong religious impulse (though his ideas were heretical for the day, because of its denial of the Trinity and other doctrinal idiosyncrasies). Not only does that explain his biblical research and interest in alchemy—which was a much weirder and more complex topic than the caricature we often discuss today—it also is the reason for certain of his scientific ideas that seem odd to us today. (For example: his idea that the Solar System cannot be stable, but requires occasional direct divine intervention to keep planets in orbit.)

When I found out the actual story of Isaac Newton’s life and thought, I confess: I felt a little betrayed. Here is the physicist’s physicist, the man who would be famous if he had made a quarter of the discoveries, devoting his life to research that is utterly discredited today. But the Newton revelation was pretty innocuous; a far worse sense of hurt comes when a hero turns out to be a terrible person in many respects.

For people who responded with disgust or with excuses, the responses were deeply personal: Feynman means something to people, though he’s been gone for over 20 years.

A few months back, the corner of the internet I inhabit was stirred up by a series of articles about the bad behavior of a prominent 20th-century physicist. The information in these stories wasn’t new—it was all drawn from biographies and memoirs published decades ago—but it was new to some people. New information or not, it was a catalyst for deeply personal responses.

The physicist at the center of the recent whirlwind was Richard Feynman, a man so strongly associated with the concept of scientific genius that one prominent biography is simply titled, Genius. Of modern physicists, only Einstein is more highly honored; among many practicing physicists, Feynman may even be considered more heroic. It’s easy to see why: his work helped establish the theory underlying all of modern particle physics, and physicists in seemingly unrelated areas use methods he developed.

I’m a physicist by training, and in the male-dominated environment of conferences and university departments, Feynman stories were common. Many of those were about his mischievous antics: breaking into safes during the Manhattan Project, donning a necktie (which he usually refused to wear) to sneak into a venue, and so forth. Others were more locker-room in tone: stories about Feynman the Player, with more than a bit of admiration for his sexual exploits.

In the accounts in biographies and Feynman’s own memoirs, though, it’s a lot harder to spin his behavior into something we should emulate. I won’t recap all the details—you can read one summary on my blog—but while he may have been a great scientist, as a human being he had many failings, particularly in his relationships with women, some of which were exploitative or demeaning.

The recent discussion largely involved people discovering this darker side of Feynman for the first time. While the conversation was broad, writers either expressed disgust, or tried to excuse him as a typical product of his times. But in both cases, the responses were deeply personal: Feynman means something to people, though he’s been gone for over 20 years.

The Feynman revelations weren’t new to me this time, but I had gone through my own period of shock and betrayal when I read his biographies. The stories we heard in class and at parties placed the genius at the center and everyone else at the periphery. More accurate and nuanced versions rightly recognize that the people Feynman harmed were every bit as real and important as he was.

I still have my own share of heroes—and slippery, complicated relationships with them. I don’t know if it’s possible or desirable to be entirely objective about those people; I’ve read their biographies and their own writings, so I know a lot about them, even if I don’t know them. Scientists, musicians, authors, philosophers … the cross-section of humanity I admire is embarrassingly large for someone who opposes the idea of hero-worship.

As with Isaac Newton, with Feynman I learned to recognize that genius is not a pure thing that pervades all of a person’s being, nor can it be. I still struggle with keeping a nuanced view in the face of unpleasant truths, and likely always will. Without such a realistic perspective, though, we’ll always feel hurt when we find out that geniuses are, after all, just flawed human beings like us.

(Also see “From Isaac Newton to the Genius Bar,” Darrin M. McMahon’s related essay, about the practical benefits that can come to society if we get over the obsession with genius.)

Matthew Francis is a physicist, science writer, public speaker, educator, and frequent wearer of jaunty hats. He’s currently writing a book on cosmology with the working title Back Roads, Dark Skies: A Cosmological Journey.