Because you are reading these words, it’s safe to say you possess consciousness—that magic of awareness that you are alive and awake, and that you are you, not somebody else. Consciousness is the scent of pine in winter, the sense of the color blue, the memory of a first kiss, the thrill of an exceptional performance—all of the rich and ineffable qualitative experiences that make a life worth living and that slide through time, knitting one moment to the next.

But while we may all be intimately familiar with what consciousness feels like, explaining why it exists or how it arises from physical and biological processes is another matter. These questions are as old as Aristotle, and yet millennia on, we still don’t have any definitive answers. For much of history, the nature of consciousness was the purview almost exclusively of philosophers and poets. It was not taken seriously as a legitimate subject for scientific inquiry because it was difficult, if not impossible, to do experiments. But over the past three decades, that has changed, as neuroscientists began to make some real headway in understanding the neural bases of consciousness-related phenomena.

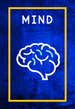

Two neuroscientists who’ve made major contributions to elucidating consciousness, of different generations, are Antonio Damasio and Anil Seth. In books that include Descartes’ Error and The Strange Order of Things, Damasio, 77, has plumbed the neural basis for feelings, emotions, and decision-making. Seth, 49, has left his mark on the field by illuminating the brain mechanisms behind perceptual experience, particularly vision, and the experience of selfhood. Both scientists published books late last year that deepen and expand their explorations of the brain and consciousness. In Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, Seth lays out his theory of “controlled hallucination”—that our perceptual experiences of the world are inventions of the brain governed by a system of predictions—and makes the case that consciousness is intimately tied to the interior of the living body. In Feeling & Knowing: Making Minds Conscious, Damasio sets out to demystify consciousness, which he argues evolved from primordial feelings such as pain and hunger, interactive processes that pair the physical with the mental and arise from a chemical orchestra deep in the viscera.

We arranged a Zoom conversation between the two scientists. We asked them to share their respective views of consciousness, ask questions of one another, and offer their wagers on whether we can ultimately solve this hardest of problems.

To start, I want to ask each of you about the titles of your respective books. So Antonio, what do you mean by “Feeling and Knowing”?

Antonio Damasio: Well, I do not think that humans can be conscious without feeling. Homeostatic feelings, such as hunger, thirst, pain, or well-being, are naturally and spontaneously conscious, or they would not be of any value to us, and the knowing is really what comes out of feeling. This spontaneous knowledge helps us manage life. If you are feeling pain, for example, this gives you very actionable knowledge about what you should do next in order to survive. That’s what I wanted to capture in as few words as possible.

And Anil, what do you mean by, “Being You”?

Anil Seth: My work has long had a dual focus: perceptual experiences of the world, on the one hand, of which vision is the easiest form to test, and then the self and emotion, the latter to a good extent inspired by the work of Antonio. But over time my interests have shifted more and more toward understanding what it means to be a self. Way back in childhood we all wonder, “Why am I me and not someone else?”, “What will happen to me after I die?”, “Is my world the same as somebody else’s?” These are very basic questions that I think we all ask and then usually lose track of as we grow up—we get “educated out” of asking them. So I wanted to bring us back to this fundamental issue of what it means to be a self in the world.

Consciousness is simpler than we make it. There’s no hard problem.

One point on which you both clearly agree is that consciousness is an embodied phenomenon, that it is because of and not in spite of our biological bodies that we have the ineffable experience of being alive in this world—a relatively recent re-conception of the relationship between mind and matter that owes great credit to the work of Antonio. But you approach this idea of embodiment in different ways in your respective books. What is the role of the body in consciousness?

Damasio: As you know, Feeling and Knowing arose out of a request from my editor: to create a book that would present my ideas in a short digestible format. My previous book, Strange Order of Things, presents many of the ideas that I discuss in the new book, but one of these is new: the hybridicity of feeling and consciousness. By this I mean that unlike straightforward types of perception such as vision, which is largely unidirectional, feelings, and thus consciousness, arise through a comingling of signals from the interior of the body with signals from the nervous system. This is a critical idea because most accounts of consciousness rely exclusively on neural processing rather than an interaction between neural and body processes, as I propose.

Seth: I do arrive at a similar endpoint to Antonio, and some others, which is that consciousness is grounded in our nature as living systems, in the fundamental biological imperative to stay alive day after day. But one of the distinctive ideas I explore in Being You is the notion that everything in perceptual experience—both self and world—is a variety of brain-based prediction, something I call “controlled hallucination.” Basically, we never perceive objective reality “as it is,” whether out there in the world or “in here” in the body. Instead, our brains receive signals from the interior of the body and from the environment and then make predictions about what these signals mean based on prior experience. These top-down predictions are then constantly corrected as the brain receives further sensory prediction error signals. This idea has a long history, with a major landmark in the 19th century when Herman von Helmholtz talked about visual perception as a process of the brain making a best guess, an inference about what’s out there in the environment.

Damasio: The way you have just expressed it, Anil, even if you don’t have your prediction machine operating at full capacity, consciousness still will emerge. Provided you have a way of accessing information from the interior of your body, you would be conscious, prediction or no prediction. So I wonder what the prediction component adds to the actual experience of consciousness?

Seth: This is a fascinating question. My hypothesis is that the contents of consciousness—whether these relate to the world or the self—are carried by top-down predictions; so predictions don’t just add to the experience of consciousness, they bring these experiences about. To test this hypothesis, we need to ask: What in the brain constitutes a minimally predictive system? For me, a minimally predictive system involves the brain encoding a generative model of its world and body—a model that is capable of generating predictions about sensory signals that can be calibrated against sensory data. It’s then an empirical matter whether conscious experiences require such generative models, or whether other simpler forms of brain-body interaction would suffice. I’m interested in how these concepts—of brain-based predictions and generative models—fits with your vocabulary, Antonio, for instance “images,” which you use to describe sensory patterns of information that are the “most abundant constituents of mind.” Maybe there is some kind of resonance here?

Damasio: I have no doubt that predictions play an important role in our mental operations, but I do not see them as necessary for consciousness to emerge.

Antonio, you said in response to my first question, that feelings lie at the core of consciousness, that they are, in fact, spontaneously conscious. Anil, do you agree?

Seth: I do also believe that feelings and emotions are central to the processes of life regulation and conscious experience, but I want to make sure I understand what Antonio means when he says that feelings are “spontaneously conscious,” because I know there is ample discussion in our field about whether some emotions are—or could be—unconscious. I think that, conceptually, there is room for predictive control mechanisms that regulate the body and guide our behavior beneath the register of consciousness.

Damasio: To avoid confusion, I think we need to make a clear distinction between feeling and emotion. I have a relatively strict definition of “feelings,” which I see as primarily related to the state of life regulation within a given organism. Hunger, thirst, pain, and well-being, which I call “homeostatic feelings,” are prominent examples. Feelings are subjective experiences. I think emotions are something quite different. Emotions are collections of acts executed in our faces and bodies and observable by others. Emotions are public. Joy, fear, and anger are prominent examples. So, is it possible to have unconscious emotions? I don’t think so.

Seth: Yes, in my book, I argue that there is a spectrum of emotions that I think could be seen as existing on a gradient between feeling and knowing. For instance, based on your definition, sadness would likely qualify as an emotion, but I believe it could also lie in the realm of feelings. It’s something that’s pretty internal, it could just be there—unexpressed. But disappointment would lie more solidly in the emotional realm, as it requires the brain to have expected something to have been better than it turned out to be, which is a more sophisticated turn. And then, we humans also have regrets. We can even have anticipatory regret, and this adds even further levels of cognitive sophistication, further levels of knowing.

Would you say that these more complicated states of emotion represent higher or more complex “levels” of consciousness?

Seth: I’m personally very skeptical of this kind of labeling, of higher and lower levels of consciousness. There is a little truth to it, of course. Unless we can agree that human beings are in some sense, more conscious than, say, an ant, we’re missing some very important things about the nature of consciousness. But to reify that observation, to treat consciousness as analogous to temperature and say, “There is a single scale of consciousness that occupies a range from absolute zero to whatever,” I think is taking things too far. This really matters when we think about the possibility of consciousness in infants and in other animals, as well in adult humans. Infants and non-human animals may be less conscious in some dimensions—for instance, the ability to engage in mental time travel and perhaps to experience things like regret—but they may be more conscious in other ways. Perhaps the immediate presence of their perceptual environment might be more vivid.

Colloquially, people also think about things like psychedelic states or meditative states as being higher levels of consciousness. But that’s a societal interpretation that’s imbued with moral or ethical value. I think consciousness is a multidimensional concept.

Damasio: I entirely agree with Anil that it’s very problematic when people talk about higher levels of consciousness or the increase in consciousness in the world. People are using very, very different concepts, and it just adds to the confusion.

Panpsychism doesn’t actually explain anything at all.

The hard problem of consciousness, set out by David Chalmers in 1995—why and how does experience arise from a physical basis—has roots going back to ancient Greece and continues to confound neuroscientists and philosophers. Anil, you say in your book that the hard problem is the wrong approach to understanding consciousness and believe we should focus our energy on what you are calling the “real” problem of consciousness: explaining why a particular pattern of brain activity—or other physical process—maps to a particular kind of conscious experience. Antonio, what do you think about the framing of the “hard” problem?

Damasio: I think Anil’s description of the hard problem is very kind. I am somewhat less generous. I think it’s a hard obstruction. And I think the framing of the hard problem, which makes it seem so impossible to explain consciousness through biology, or even to agree on what would be necessary to explain it, is probably responsible for the enchantment that people are currently having with panpsychism. Would you agree, Anil?

Seth: I think the hard problem does a good job of formalizing common intuitions about consciousness, but yes, I also think its framing constitutes an obstacle to progress. Taking the hard problem at face value does lead people naturally, and understandably, to embrace some relatively extreme metaphysical positions. Panpsychism is one of these: the idea that consciousness is fundamental and ubiquitous. The main problem with panpsychism for me is that, almost by definition, it cannot generate any testable predictions, and doesn’t actually explain anything at all. So it’s a very unproductive route to follow if you’re trying to make incremental, scientific progress on a problem. Another extreme metaphysical position which some people take is illusionism. This is the idea that consciousness doesn’t really exist, at least not how we think of it, that there’s no “problem” at all when it comes to consciousness. Although I find extreme versions of illusionism as unpalatable as panpsychism, there are milder versions of illusionism that are more useful. For example, we can be naive about what it is we’re trying to explain when we explain consciousness.

Antonio, can you say more about why you think the hard problem is an “obstruction?”

Damasio: The hard problem makes it look like consciousness is impossible to solve. It doesn’t give you any out. Every bit of evidence we have is that the mysteries of the universe have been gradually solved by science. I don’t see why consciousness should be any different. I think what engenders this possibility of us being conscious right now, of my knowing that I’m talking to you and seeing your faces on the screen and vice versa, is fundamentally linked to affect. It is a feeling, through and through, a feeling of the continuity of life in my organism. We also have reasons to believe that this core feeling is largely being produced below the level of the cerebral cortex. It is then made available to our cerebral cortex by certain subcortical structures, such as those in the thalamus and in the hippocampus. The essence of the consciousness process is actually simpler than what people want to make it. There’s no hard problem, really.

Is it possible to have unconscious emotions? I don’t think so.

Seth: I would go some of the way with you on that. I think the challenge of understanding consciousness is simpler than it’s sometimes made out to be. Just compare studying consciousness with something like the James Webb space telescope, which is just heading out to the Lagrange Point now [Ed. Note: It has now successfully arrived at LaGrange Point 2 orbit], and which aims to provide observations of some of the earliest events in the universe, including the formation of the first galaxies. It’s an insane feat of engineering, because it’s really hard to get the data on the early universe, let alone do a controlled experiment. In the case of consciousness, the brain is comparatively accessible. It’s right here. It’s not that small. It’s not that big. We can give people anesthetics and consciousness goes away and then it comes back. We can give people psychedelics, and consciousness changes, and then it changes back. In some ways, consciousness is a remarkably accessible thing to study.

But I also don’t think it’s that simple, for two main reasons. First, the relevant data for consciousness are private and subjective. But this doesn’t mean a science of consciousness is impossible, it just means the data are harder to collect. Second, the hard problem has undeniable intuitive appeal: It is true that consciousness doesn’t seem to be the kind of thing that can be explained in terms of physical processes. But the fact that something seems mysterious now doesn’t mean it will always seem mysterious, and my approach is to explain the properties of consciousness one-by-one, rather than treating it as one big scary mystery. This means dissolving rather than solving the hard problem. And here, a focus on affect and feeling is very helpful.

I strongly agree with Antonio that there’s a core affective basis to all of human consciousness: We perceive the world around us and ourselves within it with through and because of our living bodies. But how far can we take that statement? Does it imply that only living things can be conscious, a philosophical position called biological naturalism? Some people would even go further and say, all living things are conscious, which is biopsychism, a sort of biological equivalent of panpsychism, for which I don’t see a justification.

I think there’s also a temptation to expect more from a science of consciousness than scientific explanations usually provide. And that’s because we are trying to explain us. In quantum mechanics or in physics, people are more comfortable with the idea that successful theories can be counterintuitive. But we somehow want an explanation of consciousness to be completely intuitive.

Damasio: Well, we know what consciousness provides: It allows me to refer perceptions, ideas, and calculations to a specific organism, my own. It “locates” my mind in my body. How is this feat achieved? The gist of it is there, in the continuity of homeostatic feelings, positive, negative, and neutral, and in what they naturally offer: a continuous and spontaneous identification of the living organism, as the “place” where mind happens, in other words, a conscious experience. Of course, I am quite aware of the fact that many details need to be worked out, but I do not see that as impossible at all. For example, in order to generate feelings, we need peripheral nerves, spinal and brain stem ganglia (such as the trigeminal ganglion), and a variety of nuclei in the brain stem core (such as the parabrachial nucleus). I would bet that the fundamentals of feeling are actually obtained from processes generated by those components of the nervous system.

Well, this leads perfectly to a question that I wanted to ask you both, which is whether you would be willing to bet that consciousness can ultimately be solved. Christof Koch bet David Chalmers a fine case of wine that scientists would be able to identify the “neural correlates” of consciousness by 2023. Francis Crick predicted we would be able to explain consciousness by the end of the 21st century. Antonio, you just offered to bet, I think, that we will find that certain areas of the brain produce the fundamentals of consciousness. So, I wondered, if you were betting men, what kinds of bets would you make about whether and when we might solve consciousness?

Seth: People have lost many bottles of wine making these kinds of bets!

Yes, I’m sure!

Seth: I’m going to give an annoyingly equivocal answer: It depends. Sometimes, it even depends on the day. On some days I wake up in the morning and consciousness seems as mysterious as it ever did. Other times, I hear people in the academic community say, “We know nothing about how the brain generates consciousness,” and this really winds me up. We have made huge advances, especially in the last 20 or 30 years, in our knowledge of how consciousness relates to neuroanatomy and physiology, as Antonio was just explaining. I’m very optimistic that we will continue to discover and understand more and that the questions we’ll ask about consciousness will continue to evolve, too. I don’t think we’ll have a Eureka moment, where somebody says, here’s the answer and does the single experiment and we all go home.

I had a question about the soul. Oh dear.

What experiments would you design if the possibilities and funding were unlimited?

Seth: Well, science always marches somewhat in lockstep with the available technology. One of the things we still lack in neuroscience, and not just in the study of consciousness, is the ability to measure activity in the brain at high spatial resolution, high time resolution, and everywhere all at once. We can typically do one or sometimes one and a half of those three things. But being a little less facetious, some of the most interesting experiments happening in the near future are those designed to pit theories of consciousness against each other. We already have a number of candidate theories. There is one called global workspace theory, which says that consciousness happens when information is broadcast in cortical networks in a particular way. There’s higher order thought theory, which says that consciousness is all about brain regions representing the activity in other brain regions in a particular way. There are affect-based theories like Antonio’s. There are prediction-based theories, among which my version is closely related to Antonio’s. The challenge is to find the experiments that arbitrate between these different theories. When the field of physics was figuring out whether relativity could stand up or not, they designed an experiment that could actually arbitrate between Newtonian mechanics and Einsteinian relativity.

Damasio: I agree with you, Anil, on good days and bad days. There are good days when you have some clarity about a possible mechanism that could help explain the nature of consciousness and then bad days, when you realize that doing the right experiment to test that mechanism is going to be either impossible or very complicated. But another good day comes when we actually surmount that problem and make an illuminating discovery. It’s quite amazing what we have learned, for example, about the features of the peripheral nervous system, which channel signals from everywhere in the body to the brain and is responsible for the homeostatic feelings I spend so much time studying and contemplating.

For example, the spinal ganglia, which transmit information from all over our bodies to the central nervous system, happen to have a very unique feature: They are directly exposed to the molecules circulating in the bloodstream. Isn’t that interesting? Our cerebral cortices are extremely protected from the body by the blood-brain barrier: so, many molecules are barred from entering the cortex. And yet, here in the spinal ganglia, lo and behold, all of these neurons are directly exposed to the circulation of the blood. This is quite spectacular. It is also spectacular to realize that the majority of the neurons in the peripheral nervous system are neurons of a very old evolutionary vintage, and that they are completely different from the neurons that are responsible for our vision or hearing. And yet these older neurons completely lack insulation. They have no myelin to protect the conduction of an impulse. They are also open to non-synaptic contacts. I believe this direct comingling of signals from the nervous system and the body produce the hybridicity I mentioned earlier. These kinds of discoveries give me hope that we are closing in on a detailed physiology of feeling and therefore on an understanding of consciousness.

I had a question about the soul.

Damasio: Oh dear.

Yes, I know. Sorry. Anil, in your book, you suggested that the most fundamental level of consciousness, the experience of just being alive, could be called an echo of the soul. And there’s this lovely passage about that. You mention Atman in Hinduism, which contemplates our innermost essence more as breath than as thought. So I wondered, is there room for belief in the soul in your respective conceptions of consciousness?

Seth: I think there’s a case to rehabilitate the concept. One formulation of the soul is that it is an immaterial essence of you that can survive the death of the body and maybe hop into another body and perhaps resubstantiate itself and so on. This kind of soul is often associated with rationality and personal identity. But there are many other conceptions of the soul where it is less linked to reason and thinking and more closely tied to the body and bodily processes like breathing. So yeah, I think there’s a place for it, but it’s a place for a more embodied, more biological soul.

What do you think, Antonio?

Damasio: I agree that what philosophers and theologians have described as a soul is very much captured by the continuous feeling of existence that I mentioned earlier. Feelings such as hunger or thirst are occasional, but if we pause for a moment and observe carefully what goes on in our minds, we realize that “a feeling of just being” is present continuously. And when that feeling of being is not there, “you” are not there either, which is what happens when you faint or when you go under anesthesia—consciousness disappears.

And this is a question mostly for you, Antonio. You’re both a neuroscientist and a philosopher and those two fields have historically been at odds with each other on the subject of consciousness. So I wondered how does philosophy inform your position on consciousness?

Damasio: I have too much respect for the discipline to call myself a philosopher. I was never trained as a philosopher. Of course, I love philosophy. I do think that neuroscientists cannot properly study consciousness if we don’t know the history of the treatment of the problem in philosophy. But philosophers have not always considered the neuroscience of consciousness in their own work. And that is a pity because neuroscience has so many unequivocal facts to contribute.

Seth: Maybe 20 or 25 years ago, it was perfectly legitimate to be a philosopher of mind, talking about consciousness without really engaging with the neuroscience. And it was reasonable to be a neuroscientist interested in consciousness without necessarily being literate with the philosophy. But that’s changed—and changed for the better. Some philosophers are even doing experiments, and to be a serious neuroscientist of consciousness, you need to be receptive to philosophical perspectives, know the territory and be open to the dialogue. The crossover between neuroscience and philosophy is becoming more baked in, which is very promising for the field. In fact, there’s a lot more crosstalk between philosophy, neuroscience, and the medical and clinical sciences as well. Anesthesiologists have only relatively recently got into the game, talking with other neuroscientists and philosophers about what they’re doing.

So returning to the question, have we made progress? I’d say this is a reason for optimism.

Damasio: Absolutely. I agree.

Kristen French was raised by Christian Scientists, which inspired a fascination with medicine, biology and the relationship between mind and matter from a young age. She is a science editor and writer with bylines in Wired, New York, Proto, and The Verge, among other publications. New York City, where she lived for 16 years, will always feel like home, but she is now based in San Diego, California, land of surfers and sunshine.

Lead image: melitas / Shutterstock