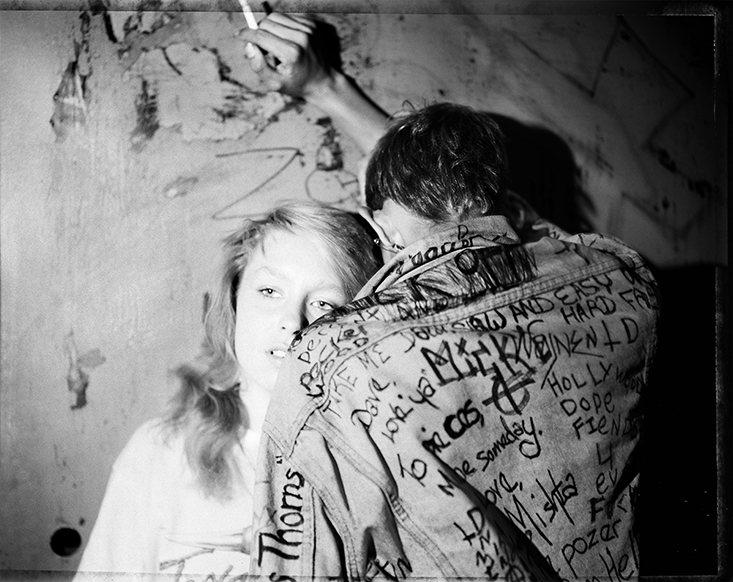

Robin Marvel was never supposed to succeed. By the time she was a teenager she’d watched her mother be violently beaten by her father and a number of boyfriends, been sexually assaulted herself, moved haphazardly around the country, become an alcoholic, and gotten pregnant by her boyfriend.

“There was never any stability at all,” Marvel says of her life with her mother. “I was always homeless, we were always being evicted or moving, the lights would be off for weeks. We would get kicked out of domestic violence shelters because she would break the rules.”

Sometimes Marvel would come home to find cocaine and mounds of marijuana on the table. “My mom was extremely unstable. She would just wake us up in the middle of the night and say ‘We’re moving to Michigan.’ Then the same thing would happen in Michigan—we’d just move back. I missed the first three months of third grade because we were living in a station wagon in Sacramento.”

Having a daughter at 17 sobered Marvel temporarily, but in a few years she began drinking heavily again. “I wouldn’t see my daughter for days,” she says. “I was just being this really awful person. I maxed out credit cards. I had a car repossessed. I didn’t understand the responsibility of paying bills and keeping good credit. And I didn’t see the importance in it either. I didn’t see the value in being able to build a financially responsible life.”

Reflecting on her perspective at the time, Marvel says, “You have no control over life, it just kind of sucks. It was just kind of a normal thing for me to live in that horrible lifestyle.”

Studies in social science and psychology have shown people like Marvel—people whose early existences are largely defined by a lack of resources, instability, and violence—often live foreshortened lives filled with risk-taking and even crime. Vladas Griskevicius, a social psychologist at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management, wants to change the way we think about people like Marvel, and the seemingly senseless choices that they make.

“The takeaway message in most of psychology is that if you grow up in a bad environment, you’re going to be deficient in some way,” Griskevicius says. “That growing up poor or in harsh conditions prevents you from flowering and reaching your potential.”

“Becoming a teenage parent may—however much most of us don’t like it—be sensible from the perspective of the person whose future is precarious.”

Drawing on core ideas in evolutionary biology and economics, Griskevicius has another story to tell. “People who grew up in a harsh environment are better adapted to thrive in that kind of environment,” he says. When you are led to believe that life has no future, it makes sense to capitalize on what you can get in the present. Human decision-making, even when it seems irrational and reckless on the surface, is characterized, Griskevicius says, by a “deep rationality.”

Studies by Griskevicius and other researchers can be seen as a response to the argument, the gist of the American Dream, that people can readily change their behavior with optimism and persistence. But the scientists’ takeaway message doesn’t rest on pessimism and futility. While adaptation to a harsh environment can lead to self-destruction, it can also sow the seeds of success.

Griskevicius’ research relies on “life-history theory,” an evolutionary biological perspective explaining how quickly and how often organisms mate and reproduce. Every organism has limited resources in time, calories, or money, and must decide, consciously or not, where to allocate those resources. They either invest them in the future by building their own health and that of their offspring, as well as by developing relationships and knowledge, or they spend them on frequent mating, focusing instead on getting as many copies of their genes out there as they can before their lives end.

For instance, rabbits don’t live long and don’t have much control over their environment in the wild, so their approach to life is basically: Reproduce quickly—and often—before you die. This is a “fast life-history strategy.” A study across 48 mammal species found that higher mortality rates predicted early maturation and large litters of small offspring, ensuring that not too much energy was invested in each baby.1 On the other hand, later maturing animals, like elephants, have long, more predictable lives, so they produce one calf at a time and invest a great deal in each. They live a “slow life-history strategy.”

Humans, in a life-history perspective, are closer to elephants than we are to rabbits. But there’s variation within each species. People who grow up in harsh or unpredictable conditions often unconsciously adopt faster strategies for getting through life, while people raised in largely stable conditions adopt slower life strategies.

Jay Belsky, a professor of human development at the University of California, Davis, predicted 25 years ago that growing up under conditions of adversity would accelerate sexual maturation, a prediction borne out by research.2 A 2010 study found that, on average, girls who grew up in a household lower in socioeconomic status (measured in the study as a combination of household income and father’s education and occupation) had their first period at a younger age: Their bodies sensed instability and wanted to get on with things.3

Further, in a study across 170 countries, women who lived in countries with shorter life expectancies had their first baby at an earlier age.4 The same pattern was found across Chicago neighborhoods.5 Across counties in the United States, lower income and higher rates of violent crime were associated with mothers giving birth at a younger age.6 In England, deprived areas led to lower ages at first birth, lower birth weight, shorter breastfeeding periods, and a higher rate of reproduction.7 Another study analyzed the causal pathway for such effects: Among English subjects, lower socioeconomic status in childhood led to greater childhood adversity, which led to increased emotional and behavioral maladjustment, which led to a younger age of reproduction.8

To Belsky, these findings make sense. “Becoming a teenage parent may—however much most of us don’t like it—be sensible from the perspective of the person whose future is precarious,” he says. Drawing an economic analogy, he notes that saving money is generally considered a worthwhile and honorable endeavor, unless you’re in an inflationary economy.

Griskevicius has used an economic model to understand similar life circumstances and how people’s life choices might help them adapt. “The heart of economics is how people make tradeoffs, because everyone has limited resources,” he says. “The math underlying all economic theory and all life-history theory is essentially the same—they’re just looking at different types of resources.”

For one of their papers, Griskevicius and his collaborators looked at what drives family-planning decisions. In an experiment, they had undergraduate participants state at what age they wanted to get married and at what age they wanted to have their first child. They also reported their family’s financial status growing up. Those who grew up poor wanted to get married and have kids earlier than those who grew up wealthy. A companion experiment found that the lower a subject’s household income growing up, the less the subject wanted to pursue education and a career before starting a family.

Difficult conditions over the first five years of life were associated with delinquent, aggressive, and criminal behavior at age 23.

According to Griskevicius, these studies show that when someone’s early life is defined by a lack of money and resources, his or her conscious and biological drives can signal that trying to build a solid career before reproducing is likely a losing proposition. The wise decision appears to be: Get married early and have kids fast.

The studies reveal two other important phenomena. Before answering the questions, the subjects read a fake newspaper article about an increase in violence in the U.S. Other subjects in the same study read a less threatening article. For these other subjects, childhood family income had no effect on family planning. It was the slight sense of threat that had a unique influence. Second, subjects also reported their current financial status. Unlike their childhood financial status, this had little effect on when they wanted to start a family, suggesting that life-history strategy gets locked in early.

A longitudinal study further explored the effect of early conditions.9 Using data on 165 young adults, researchers found that difficult conditions over the first five years of life—but not conditions over the next 10 years—were associated with delinquent, aggressive, and criminal behavior at age 23, as well as the number of sexual partners they’d had. The study revealed the effect of childhood socioeconomic status was smaller than the effect of childhood unpredictability: moving around a lot, having father figures come and go, having a mother with inconsistent employment.

Together, poverty, violence, and uncertainty all point to a fast life-history strategy: seizing the moment with little regard for a future that may not arrive.

Aurelio José Figueredo, a psychologist at the University of Arizona who studies life-history theory, puts the strategy in a stark light. “I am reminded of the slogan ‘Live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse,’ ” he writes in an email. “It is not about a long, happy, or healthy life: Those are slow life-history values. Think Thomas Hobbes: ‘Nasty, Brutish, and Short.’ ”

In their book, The Rational Animal, Griskevicius and Douglas T. Kenrick feature a host of high-profile people who grew up in fast-life situations, then became wildly successful, only to take an enormous fall.

M.C. Hammer grew up with eight siblings and a single mother in a housing project in East Oakland, California. He went on to earn tens of millions of dollars in music but quickly spent it all; several racehorses later, he was millions in debt. Mike Tyson, one of the most successful boxers of all time, grew up with a single mother in a tough Brooklyn neighborhood. He too earned a fortune before, two Bengal tigers later, he found himself millions in debt. The authors also spotlight Larry King, who grew up with a single mother in another poor Brooklyn neighborhood. After making it big as a radio and TV host, he too, several ex-wives later, had to declare bankruptcy.

“Looking through an evolutionary lens,” Griskevicius and Kenrick write, “it becomes clear why these three men started spending their monetary windfalls as soon as the money hit their bank accounts: Their brains were calibrated to live fast because they did not know what tomorrow would bring.”

In the lab, Griskevicius and his colleagues identified the kinds of decisions that cause such downfalls. They found that threatening cues like stories about violence and economic recession led those who’d grown up relatively poor to take risks (gambling on large monetary rewards rather than settling for smaller ones),10 prefer immediate gratification (choosing smaller amounts of money now over larger ones later), and tend toward excess consumption (yearning for luxury items at the expense of savings).11 The experiments raise the question of why people from more stable, financially secure lives, when faced with the same cues, don’t make the same rash decisions. (Well, not as often.) In fact, in some studies, threatening cues reduced the rash decisions of those from stable childhoods.

“I remember sitting in my living room and looking around and going, ‘This is not the way I want my story to end.’ ”

In a 2014 paper, Griskevicius and Chiraag Mittal provided an explanation. They found that a threatening cue—an article about an economic recession—led subjects from a poor background to prefer immediate rewards over larger delayed ones, and led subjects from a wealthier background to prefer the delayed rewards.12 The mediating effect, they discovered, was a sense of control, a belief that one can achieve things one sets one’s mind to. Uncertainty leads those from difficult backgrounds to become more impulsive and less persistent. It leads those from less tumultuous backgrounds to become less impulsive and more persistent. Mittal and Griskevicius explain that those from stable backgrounds may overestimate their sense of control in a time of uncertainty because it recalls a strategy that has worked for them for most of their lives. They save up and invest in the future, for a period when times will be less hard. For those from unstable backgrounds, their way of life is constantly telling them to expect calamity.

Those born to a fast life-history strategy, though, don’t always crash and burn. In one of their papers, Griskevicius and Mittal quote 50 Cent: “You can take me out of the ’hood, but you can’t take the ’hood out of me.” For many fast life strategists, that might turn out to be a death sentence, but in the rap star’s case, a fast life-history may have been a professional advantage. Not only did his experiences give his lyrics street credibility—he grew up in a blighted neighborhood in Queens, New York, and sold drugs at the age of 12—but his gambling instinct undoubtedly helped him to put the rap game in a chokehold, allowing him to succeed in an industry where timidity gets you nowhere.

“It is plausible that 50 Cent and others may have found ways to boost their own sense of control in order to become less impulsive,” Mittal explains. “Another possibility is that 50 Cent’s early success created a more financially stable and predictable world for him, which in turn reduced impulsive tendencies.” In one of their experiments, Mittal and Griskevicius showed that when subjects recalled being in control of a situation, the difference between people from low and high socioeconomic classes was erased. Given that fast life-history strategies are triggered in uncertain situations, a stable environment can work wonders.

To Belsky, the social message of life-history theory is clear. “We can’t expect people who grow up under adversity, who are impoverished, who live in a dangerous and hostile world, who can’t walk the streets without fear, to be ‘moral upstanding citizens’ because we want them to be,” he says. “Biology may be saying, take the risk, take advantage of others, hit first and ask questions later. That creates an imperative on our part to say, if we want good citizenry, we need to provide good conditions, so they can learn that the future is predictable, that others care for me, that I can control my destiny.”

At age 23, Marvel felt like a victim and was full of self-pity. But her husband was a terrific cheerleader, and her oldest daughter gave her inspiration. One day something clicked. “I remember sitting in my living room and looking around and going, ‘This is not the way I want my story to end,’ ” she says. “I was looking at my daughter and I wanted to be a good example for her.”

On her aunt’s bookshelf she found a book called The Art of Happiness. “I started reading it, and that was when I started learning that I was in control of my happiness.” She read more self-help books and found ways to manage her stress. “I do have stressful days,” she says, “but I have really programmed myself with a new train of thinking.”

Soon, Marvel decided she wanted to share her newfound wisdom with others, and wrote a newsletter on empowerment. When local businesses declined to stock the newsletter, she almost gave up. That’s when her husband suggested she start a website. The site got a great response. Marvel realized there weren’t any good hands-on workbooks for her five daughters, so she decided to write one herself. Her effort was welcomed by a small publisher, and today, at age 36, Marvel has written five books for kids and adults, with a sixth to be published this year.

“A lot of times people feel limited, and don’t know they can become something, because it was just a certain way for so long,” she says. Nobody has told them they’re worth anything. “I want to be that voice.”

At home in Hersey, Michigan, Marvel gives her daughters the stability and mental tools she never had. Each morning, she sits down with her 4-year-old and asks her a question: “Today’s your day. Who’s in charge of your day?”

Matthew Hutson is a science writer who’s written for Wired, The Atlantic, and The New York Times. He is the author of The 7 Laws of Magical Thinking.

References

1. Promislow, D.E.L., & Harvey, P.H. Living fast and dying young: A comparative analysis of life-history variation among mammals. Journal of Zoology 220, 417–437 (1990).

2. Belsky, J. The development of human reproductive strategies: Progress and prospects. Current Directions in Psychological Science 21, 310–316 (2012).

3. James-Todd, T., Tehranifar, P., Rich- Edwards, J., Titievsky, L., & Terry, M.B. The impact of socioeconomic status across early life on age at menarche among a racially diverse population of girls. Annals of Epidemiology 20, 836–842 (2010).

4. Low, B.S., Hazel, A., Parker, N., & Welch, K.B. Influences on women’s reproductive lives: Unexpected ecological underpinnings. Cross-Cultural Research 42, 201–219 (2008).

5. Wilson, M. & Daly, M. Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighbourhoods. British Medical Journal 314, 1271–1274 (1997).

6. Griskevicius, V., Delton, A.W., Robertson, T.E., & Tybur, J.M. Environmental contingency in life history strategies: The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on reproductive timing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100, 241-254 (2011).

7. Nettle, D. Dying young and living fast: Variation in life history across English neighborhoods. Behavioral Ecology 21, 387–395 (2010).

8. Nettle, D., Coall, D.A., & Dickins, T.E. Early-life conditions and age at first pregnancy in British women. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278, 1721–1727 (2011).

9. Simpson, J.A., Griskevicius, V., Kuo, S.I., Sung, S., & Collins, W.A. Evolution, stress, and sensitive periods: The influence of unpredictability in early versus late childhood on sex and risky behavior. Developmental Psychology 48, 674–686 (2012).

10. Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J.M., Delton, A.W., & Robertson, T.E. The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: A life history theory approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100, 1015–1026 (2011).

11. Griskevicius, V., et al. When the economy falters, do people spend or save? Responses to resource scarcity depend on childhood environments. Psychological Science 24, 197–205 (2013).

12. Mittal, C., & Griskevicius, V. Sense of control under uncertainty depends on people’s childhood environment: A life history theory approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107, 621–637 (2014).