On May 29, 1810, Katherine Fritsch, a sister in the Moravian Church, boarded a coach in Lititz, Pennsylvania, along with a group of her friends and began the 75-mile trek to Philadelphia. Fritsch noted in her diary the one city site she most wished to see: Peale’s Museum. On the grounds of the museum, whose two buildings sat on State House Square, with rows of trees and manicured lawns, Fritsch passed through a menagerie that included a large cage with a live eagle sitting “right majestically on his perch—above his head a placard with this petition on it: feed me daily for 100 years.”

From the yard, Fritsch went into the Peale Museum proper, through a door with “Whoso would learn Wisdom, let him enter here!” posted above. Fritsch walked past a turnstile that rang chimes to announce visitors. She walked up the stairs and into the Quadruped Room, which included a moose, llama, bear, bison, prong-horned antelope, hyena, and a jackal. She explored the Marine Room, overflowing with fish, amphibians, lizards, sponges, and corals. In the Long Room, glass cases were filled with hundreds of birds set against backdrops matching their natural environments; she saw insect cases in which the specimens could be rotated under a microscope. Fritsch didn’t get to see the museum’s mammoth skeleton, but noted in her diary that “all our talk was of how delightful had been our visit to the museum.”

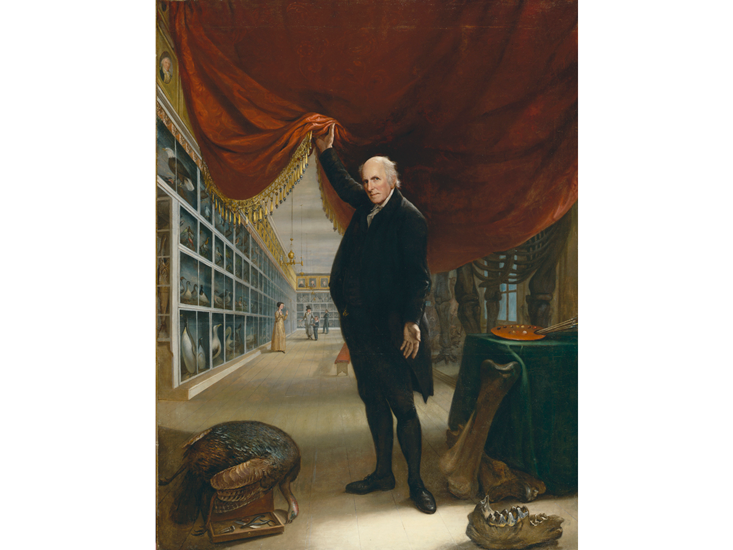

Fritsch was not the only one who felt that way. From the time Peale’s Museum had opened its doors in 1786, annual attendance had averaged more than 10,000 people. Born both of science and art, it was the first true museum in the fledgling United States and the first must-see attraction not only for Philadelphians but for visitors from around the U.S. and the world. The museum’s creator, Charles Willson Peale, saw the museum as a national good. The “very sinews of government are made strong by a diffused knowledge of this science,” he wrote. The museum’s success made Peale a proud man for many years. It embodied the age of Enlightenment in the new world. After a visit, the French philosopher Comte de Volney proclaimed the museum housed “nothing but truth and reason.” But national funding for truth and reason foundered on the shore of politics. And then the circus came to town.

Peale was born in Maryland in 1741. When he was 9, his father, a schoolteacher, died, leaving the family in poverty. Peale was apprenticed to a saddler at age 13, but spent almost as much time tinkering with mechanical devices of all sorts as he did saddling. His other interest lay in paint brushes and sketching pads. Ambitious as could be, Peale became the Colony’s most famous portrait painter. In 1771, Peale met Martha Washington and convinced her that Colonel Washington should sit for him—the first of 25 portraits, miniatures, mezzotints, or sculptures he would do of the soon-to-be general. Peale also painted portraits of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton. He named most of his 17 children after famous painters, including Rembrandt, Rubens, and Titian.

A true autodidact, Peale saw himself as a naturalist and scientist. And any self-respecting deist of the Enlightenment should have a museum. Fortunately, Peale knew all the right people. Robert Patterson, professor of mathematics at the University of the State of Pennsylvania, gave Peale his first specimen for the museum, “a curious fish called the paddle fish caught in the Allegheny River,” Peale wrote. Ben Franklin sent his friend the body of an angora cat that Madame Helvétius had given him when he departed Paris, and Washington sent the body of a just-deceased golden pheasant from the aviary of Louis XVI that the general had received as a gift from the Marquis de Lafayette. Other specimens soon came flooding in.

Peale wrote that society raised roadblocks to women, which didn’t allow them to pursue science.

In a letter to Jefferson, Peale explained that his goal for the museum was to bring together “a variety of interesting subjects of Nature … collected in one view as would enlighten the minds of my countrymen, and, demonstrate the importance of diffusing a knowledge of the wonderful and various beauties of Nature, more powerful to humanize the mind, promote harmony, and aid virtue than any … yet imagined.”

Peale, a former member of the Philadelphia Militia, was a true-blooded patriot. He created an effigy of a double-faced model of Benedict Arnold in a carriage, dressed in a red coat and holding a letter to Beelzebub with the devil standing behind him shaking a purse full of money. When it came to his museum, he had no intent of curating the sort of European hall that catered only to “particular classes of society only, or open at such turns or at such portions of time, as effectually to debar the mass of society, from participating in the improvement, and the pleasure resulting from a careful visitation,” he wrote. His museum would be open to all—“the unwise as well as the learned.”

Peale held progressive views on women and children, and because he knew that a family-friendly venue would attract more visitors, he reached out to bring women and children into his museum. Women were not only encouraged to visit the museum, Peale wanted them to contribute to the enterprise, sending in samples and sharing ideas. Society, he believed, raised roadblocks to women “which allow no time for them to devote in the arduous pursuits of science,” but, he was quick to point out, “when females have devoted themselves to these pursuits they have given every demonstration of the intensity and depth of their intellectual powers.” He wanted to tap into those powers to better the museum and the plight of women.

Reverend Manasseh Cutler, a respected naturalist of the day, who had gained fame for his bravery as a chaplain during the Revolution, was an early visitor to Peale’s Museum in 1787 and was struck by the exhibits “arranged in a most romantic and amusing manner.” He describes two dioramas—a mound with trees and an artificial pond, each the result of Peale having spent many a morning “dressing the museum in moss.” The pond was stocked with fish, geese, ducks, cranes, and herons, “all having the appearance of life, for their skins were admirably preserved.” On the beach around the pond Cutler was dazzled by an assortment of “shells of different kinds, turtles, frogs, toads, lizards, water snakes, etc.” Cutler’s diary ends: “Mr. Peale’s animals reminded me of Noah’s Ark, into which was received every kind of beast and creeping thing in which there was life. But I can hardly conceive that even Noah could have boasted of a better collection.”

From the outset, the museum was meant to be a collaborative effort. Jefferson, Hamilton, James Madison, Gouverneur Morris, famed astronomer David Rittenhouse, and naturalists Benjamin Smith Barton and William Barton, sat on the museum’s board of directors. But this museum was not to be some highfalutin society club. Peale turned more often to his fellow citizens than to his board of directors to contribute what they could, be it specimen or knowledge. Each year, he would publish dozens of newspaper advertisements that included not just a call for specimens, but lists of new specimens received of late, information about new exhibits, changes to museum hours of operation, and perhaps strangest to our eyes, praise or admonitions of the way the public was responding to activities at the museum.

A few years after it opened, in a series of parades, young boys (and older men) moved all the exhibits to the museum’s new home in the American Philosophical Society’s Philosophical Hall. Peale and his family moved their own home to the basement of the museum, so as to better manage the ever-growing enterprise. Soon, the museum outgrew even Philosophical Hall and moved to the State House (what we now call Independence Hall), above the rooms where the Declaration of Independence were signed, and below where a soon to be rather famous bell rang each day.

In 1801, Peale and a team undertook the first major paleontological excavation in the U.S. Near Newburgh, New York they dug up, and then painstakingly reconstructed, the complete skeleton of a mammoth (technically, it was a mastodon, but that distinction did not yet exist). It was quite the sight and caught the fancy of locals. “Every farmer with his wife and children, for twenty miles round in every direction flocked to see the operation,” wrote Peale’s son Rembrandt. The Mercantile Advertiser soon ran tantalizing headlines like “Bones of a Mammoth or some other Wonderful Animal,” titillating readers with tales of “a monster so vastly disproportionate to every creature; as to induce a momentary suspension of every animal faculty but admiration and wonder.”

Ben Franklin sent his friend the body of an angora cat and George Washington sent a golden pheasant.

In Skeleton of the Mammoth, a broadside that Peale posted across Philadelphia in 1802, he informed readers that though “numerous have been the attempts of scientific characters of all nations to procure a satisfactory collection of bones,” he and his museum had at last done just that. Peale even had one of the museum employees distribute the broadside throughout the city while on horseback wearing “feathered dress” and preceded by a trumpeter.

Peale’s team dug up enough bones to reconstruct two mammoth skeletons: the one that sat on exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum, and a doppelgänger that went on tour in England, under the watchful eyes of Peale’s sons Rembrandt and Rubens. Before they left, their father gave them a bon voyage present, hosting a dinner for 13 inside the rib cage of the mammoth that was staying put in Philadelphia.

Soon a mammoth craze, arguably the first craze to sweep the country, was underway. People spoke of mammoth squashes, mammoth radishes, mammoth peaches, and mammoth loaves of bread. The Columbia Repository newspaper ran a story of a 1,300-pound mammoth cheese made from milking the cows of each of the 186 farmers in the town of Cheshire, Massachusetts. The cheese was sent to President Jefferson, who was delighted at what he deemed “an ebullition of the passion of republicanism.”

What better time to seek federal support for the museum than with the mammoth exhibit causing such a stir and his now longtime friend Jefferson sitting in the Executive Mansion? “I wish to know your sentiments on this subject, as to whether the United States would give an encouragement, and make provision for the establishment of [my] museum in the city of Washington,” as the country’s national museum, Peale wrote. Jefferson was understanding of his friend’s appeal for national support: This was, after all, a president who would soon be using the East Room of the Executive Mansion to lay out a few of his own mammoth bones.

“No person on earth can entertain a higher idea than I do of the value of your collection nor give you more credit for the unwearied perseverance and skill with which you have prosecuted it,” Jefferson replied, “and I very much wish it could be made public property.” But Jefferson claimed his hands were tied by Congress. “I must not suffer my partiality to it to excite false expectations in you, which might eventually be disappointed,” because many in government “denied that Congress has any power to establish a National Academy.” Disappointed, Peale accepted Jefferson’s decision, or at least told the president as much.

Peale officially retired as director of the museum in 1810, but had his hand in museum affairs for the next 17 years, until he was laid to rest at age 85. His Philadelphia Museum lived on, managed by various of his sons (and a nephew). One son, Rembrandt, opened a spinoff Peale museum—the first building in the United States that, from blueprints on, was designed as a museum—in Baltimore in 1814, and Rubens followed with another spinoff in New York City in 1825, on the very day that New York was celebrating the completion of the Erie Canal.

By the 1840s, the revolutionary war generation was gone, and Americans were becoming less and less interested in the sort of entertainment offered at the Peale museums. Dime store museums, with their magicians, musicians, actors, charlatans, freaks, ventriloquists, and animal acts, each claiming to be the most marvelous of them all, were on the rise. The country had entered a period of maturity and people now had more money for leisure per se. But with so many people now living in large, crowded cities, surrounded by strangers, they were drawn to dime store museums that advertised escapism:

Come hither, come hither by night or by day,

There’s plenty to look at and little to pay…

If weary and heated, rest here at your ease,

There’s a fountain to cool you and music to please

No one understood that better than P.T. Barnum, a businessman and showman, who was a master at promoting hoaxes. In 1841, before he founded his traveling circus, Barnum opened his American Museum in lower Manhattan, all too close to Rubens Peale’s museum, and used it as a showcase for freak shows and melodramatic plays. Rubens couldn’t compete and soon closed his museum and sold the contents to Barnum. Barnum swooped in and bought out the Peale museum in Baltimore as well. In the spring of 1849, Barnum opened a branch museum of his own in Philadelphia, in the Swaime Building, a few blocks from Peale’s Philadelphia Museum. Soon Barnum wrote his partner Moses Kimball that “he’d kill the other shop in no time.” He did. The Philadelphia Museum’s last advertisement ran on Aug. 27, 1849, and soon after, the United States Bank held a public auction of all the items (aside from the paintings) in the museum. Barnum was there, and bought it all, lock, stock, and barrel.

At Barnum’s American Museum, alongside many of the exhibits and fossils from Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, as well as the Peale branch museums that had stood in Baltimore and New York City, the Fiji mermaid, the head and torso of a monkey sewn to the back half of a fish, was on display. General Tom Thumb, a dwarf, danced and sang in Revolutionary War regalia. The museum attracted 15,000 people a day. Or so Barnum claimed. Nobody checked.

Lee Alan Dugatkin is a historian of science and an evolutionary biologist at the University of Louisville. He is the author of Behind the Crimson Curtain: The Rise and Fall of Peale’s Museum, and many other books, including Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose and How to Tame a Fox and Build a Dog.

Lead image: OrdinaryJoe / Shutterstock