Elephants

When I sat down with Iain Douglas-Hamilton at his home in Nairobi to learn how he went from deploying the first radio collars on elephants in 1968 to deploying the first GPS collars on them in 1995, he told me about an elephant named Parsitau. “We put a prototype on him and it lasted for all of 10 days, and we thought this was absolutely the cat’s whiskers.”

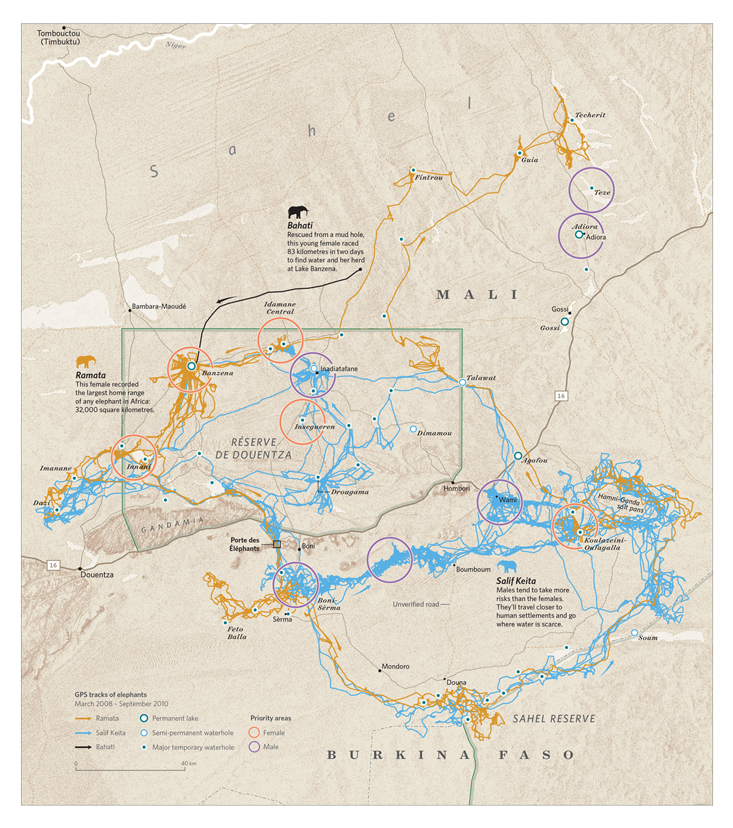

Recording four locations per day, those 40 GPS points were the first ever recorded on an animal in Africa. “It was so incredible,” Douglas-Hamilton recalled. “Here was a collar that would go across international borders, work by day, by night, inside forest, outside forest, up hills, down hills.” Plus, GPS was far more precise than radio or traditional Argos satellite tracking.

Today, the breakthroughs are still coming. Just a few years ago, Douglas-Hamilton’s research and conservation organization, Save The Elephants, partnered with Google to develop a way for GPS locations to feed directly into Google Earth. And they have since created their own real-time tracking app for phones and tablets in partnership with Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen and his company, Vulcan.

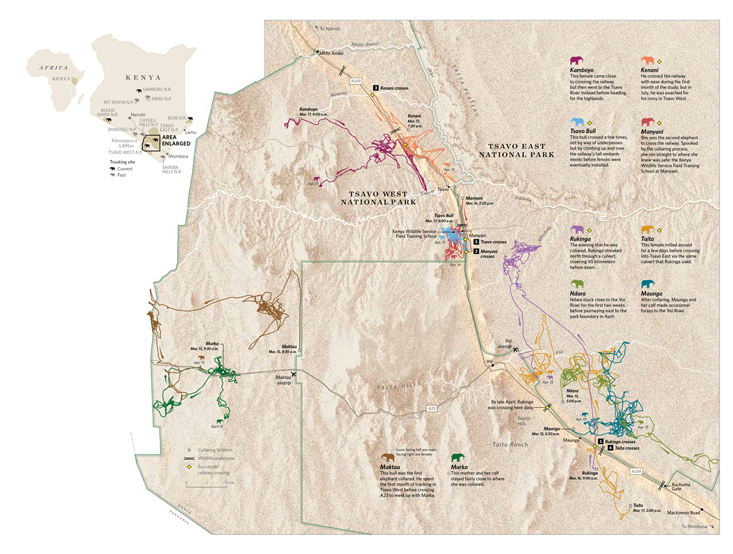

Douglas-Hamilton was reviewing the latest collar data from Tsavo on his laptop one of the nights we met. “We haven’t had these collars on for three days,” he said, “and two of the elephants have already crossed the railway. I nearly died when I saw this! There’s Manyani. She was collared up there, streaked down, crossed, and fled to safety. And guess where safety was?” Douglas-Hamilton pointed to a building beside the road. “This is the main Kenya Wildlife Service ranger training station. Look, she’s within 500 meters of it. She’s found the human beings she likes. That’s hot stuff from the horse’s mouth.”

Save The Elephants currently has more than 300 active collars across eight African countries. New stories appear in the tracks every day.

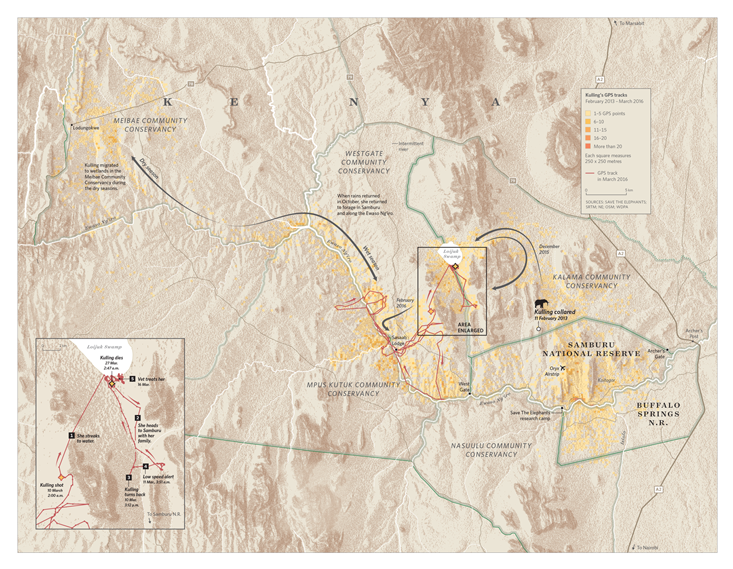

The elephants of Samburu spend more than half the year outside the reserve boundaries. In the box above, we show where an elephant named Kulling spent the last three years of her life. Some of her favorite areas included Loijuk Swamp and various spots along the Ewaso Ng’iro River.

In early 2016, Kulling was shot by nomadic herders. Loijuk Swamp had water for the first time in 10 years, drawing both wild elephants and the young herders, who had brought their livestock to drink. The elephants scared them, so they shot, hitting and killing Kulling.

STE thinks education is key to resolving human-animal conflict. A few weeks after Kulling died, STE met with herders and elders from the Loijuk community to share a meal and recall the old ways of liv- ing in peace with elephants.

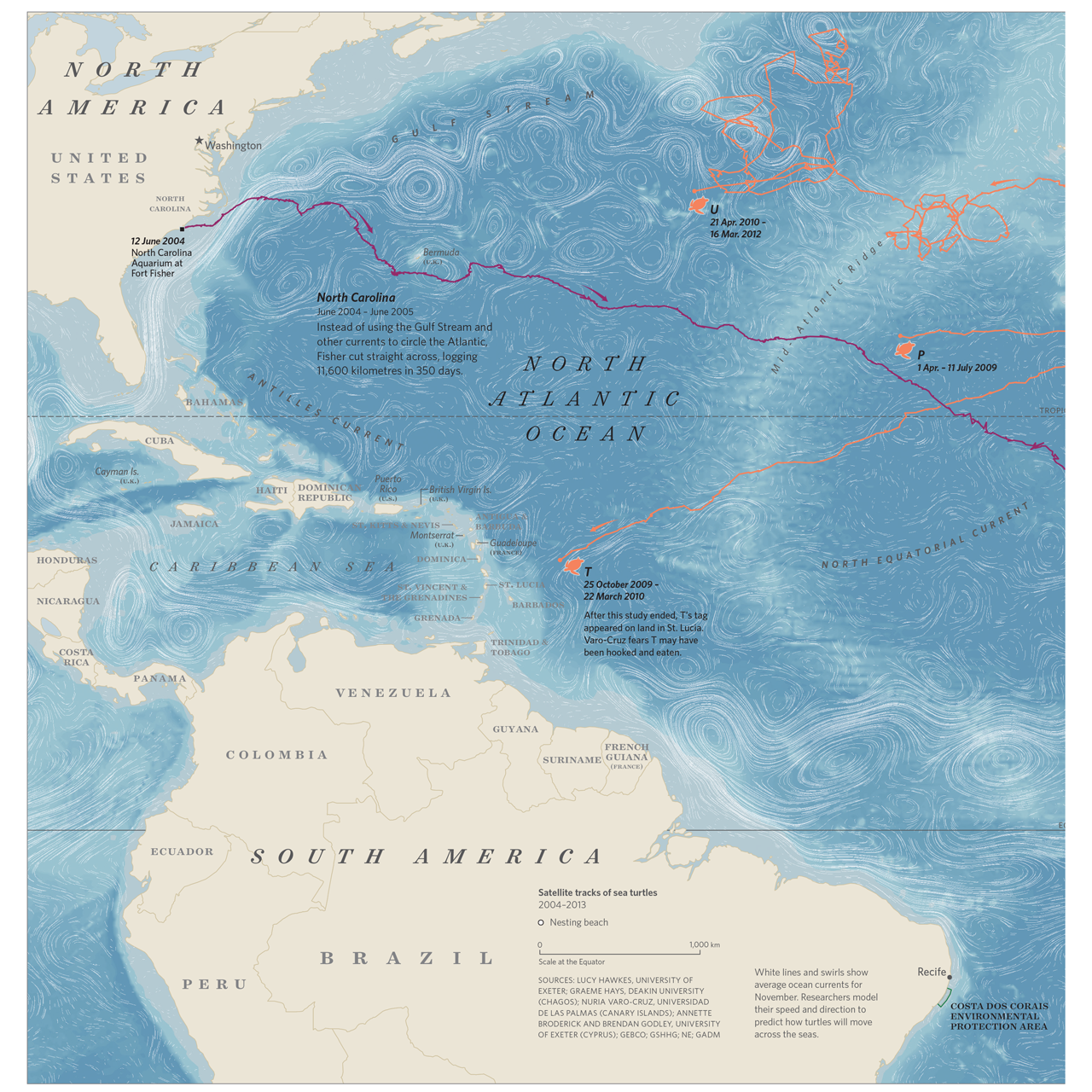

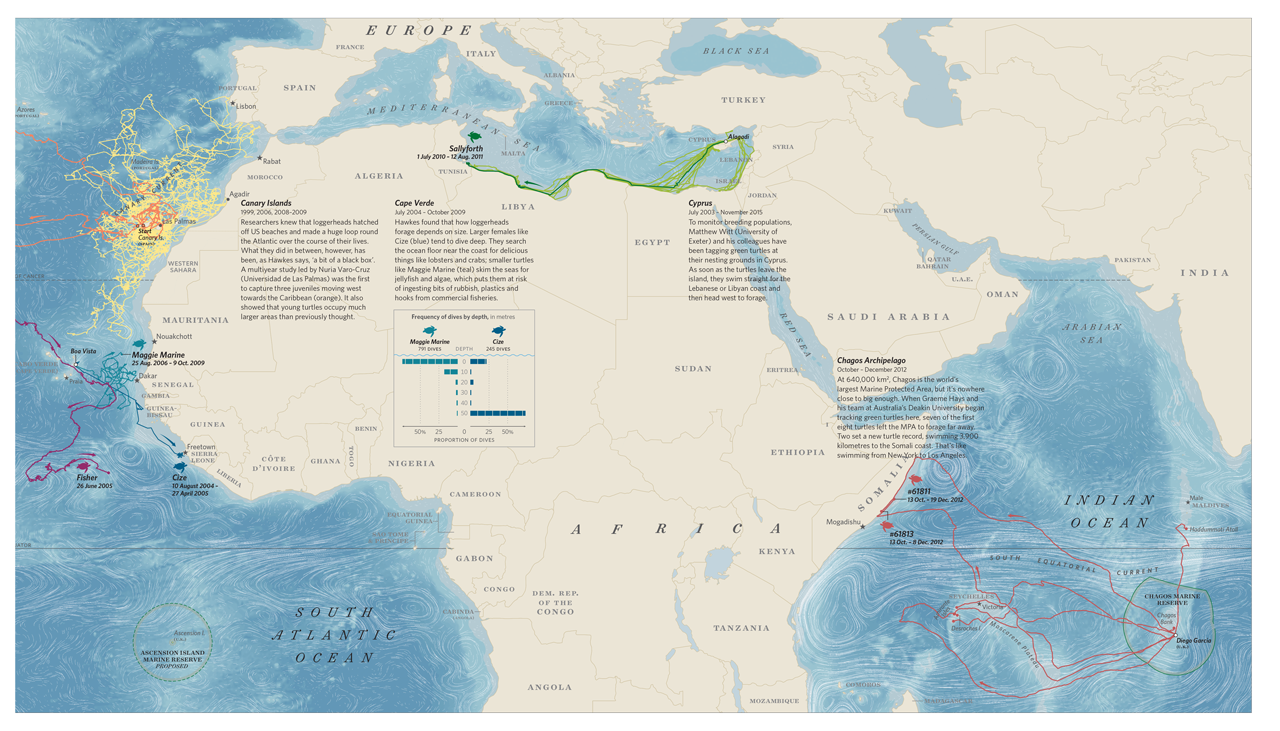

Turtles

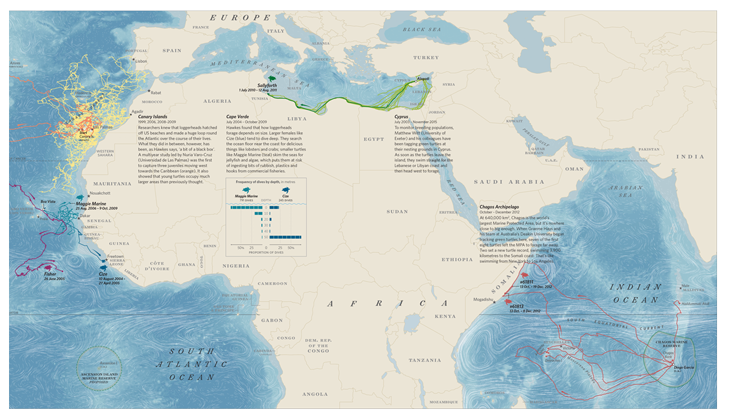

“My god, there’s a lot of turtles on here,” said Lucy Hawkes, a member of the Marine Turtle Research Group at the University of Exeter. She was scrolling through a database of their active tracking projects: “We’ve got Ascension, North Carolina, British Virgin Islands, Cape Verde, Cayman Islands, Mexico, Cyprus, Dominican Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Israel, Kuwait, Lampedusa—that’s Italy—Mozambique, Guadalupe, Montserrat, Oman, Peru, [she takes a breath] Scotland, Turkey, Sri Lanka, and Greece.” Total number of tags deployed: 443 and counting.

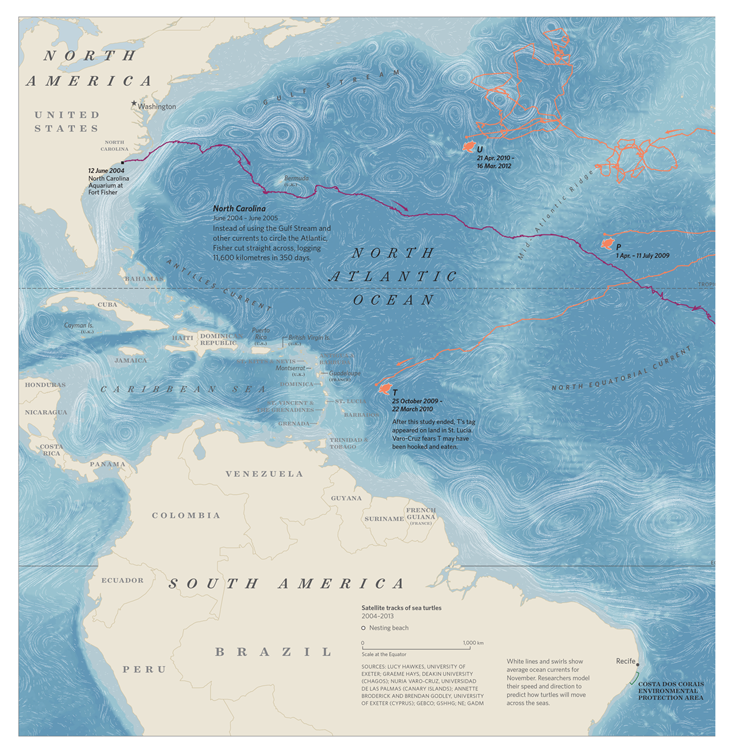

One of her first traveled on a loggerhead turtle named Fisher. In 1995, biologists from the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher found him on a nearby beach. He was weak and underweight, so they brought him to the aquarium’s rehabilitation center. Eight years later, Fisher was 40 kilograms and outgrowing his adoptive home.

His caretakers loaned him to Newport Aquarium in Kentucky for an exhibit presciently titled Turtles: Journey of Survival. By his 10th birthday, Fisher tipped the scales at 70 kilograms. He was ready to hunt in the wild. On June 12, 2004, Hawkes stuck a tag on Fisher’s shell and released him into the Atlantic. She expected him to ride the Gulf Stream to Spain.

But Fisher had other plans. “He did a straight line to Cape Verde,” Hawkes said, “which, bizarrely, is exactly where he should be at 10 years old. It was as if he thought, ‘I’ve got to catch up with everyone.’ ” Imagine that. After 10 years in captivity, Fisher knew where he needed to be, at what time, and how to get there.

Reprinted from Where the Animals Go: Tracking Wildlife with Technology in 50 Maps and Graphics by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti. Copyright © 2017 by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.