Are art and science of distinctly different cultures? The former often seems fixated on human experience, the latter on physical processes.

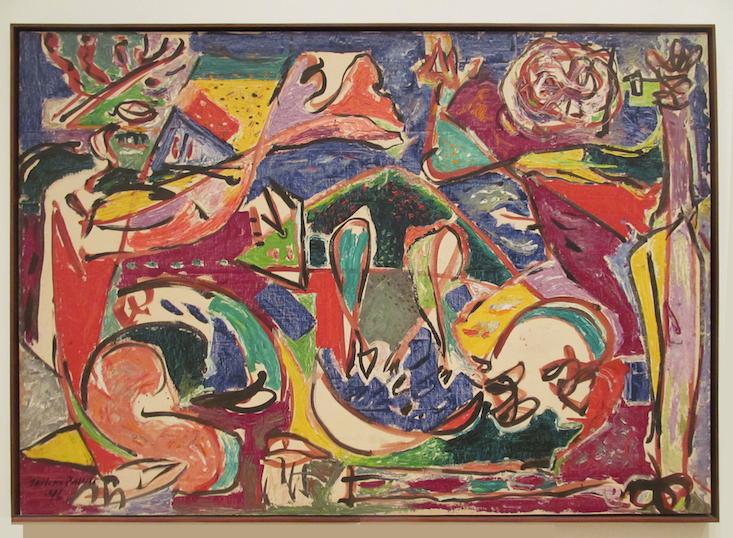

In his most recent book, Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures, published this year, the Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel argues that such a separation no longer exists. The best-known abstractionists, like Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Dan Flavin, and Willem de Kooning, Kandel writes, effectively created “new rules for visual processing.” Abstract art, says Kandel, is therefore the key to understanding both how art and science inform one another, and together, they might open up entirely new ways of seeing and imagining. Where figurative painting provides the human brain with clear visual information—images of a person, a house, a boat, etc.—abstract art reduces, he says, “the complex visual world around us to its essence of form, line, color, and light.”

In doing so, Kandel noted in our conversation, abstract art engages different parts of our minds, conjures more visceral responses, and just might make us more creative.

Why should we think of art and science as more connected than we often do?

Well, some people originally felt that the humanists and the scientists used different methodologies and had different goals. I don’t think that really continues to hold weight. Scientists can take biology of schizophrenia, depression‚ et cetera, and these are perfectly humanistic concerns. Many artists use experimental methods in order to achieve their end. They approach it very much like scientists do.

How do visual artists use methods similar to those used by scientists?

Trial-and-error is the methodology. I mean, Jackson Pollock taking the canvas off the wall, putting it on the floor and dipping painting on it. You can’t be more experimental than that. Rothko deciding, I don’t care for figuration; I don’t care for shapes on the canvas; I just want to see the pure color. Wow. I mean, that’s pretty radical stuff.

I did a Charlie Rose program with the artists Richard Serra and Chuck Close, and they said, “Creativity is for amateurs. We go out there and we solve problems. We set tasks for ourselves and we solve them.” I think the similarities are really becoming quite obvious. Certainly in the abstract expressionists—the New York group—they all ended up doing very different things when they started doing it, and they did it step-by-step as they moved from figuration to abstraction, becoming progressively more abstract in distinctively different ways.

Why do we respond more emotionally to abstract art than we do to figurative art?

When we look at abstract art it requires more of our imagination. It leaves many details unspecified, and we have to supply those details. That—for people who can do it—is very pleasurable. Some people don’t like it all, but for people who can enjoy their own creativity, it’s very satisfying.

What are the “bottom-up” and “top-down” approaches to comprehending art?

The whole idea of bottom-up and top-down was instigated by Ernst Gombrich’s work on art. He realized that when one looks at a painting—as when one looks at a person’s face—all one sees is the light reflected off the surface, the light reflected off the face, for example. That’s nowhere near enough information to allow you to reconstruct the face, and we recognize our relatives and our friends with enormous facility. So there must be other sources of information.

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz supplied that information when he pointed out that, in addition to the light bouncing off the face, there are bottom-up and top-down processes. The bottom-up processes are built into the brain. The human brain has evolved over thousands of years, so it has built-in mechanisms that make very good guesses from incomplete information. If they see a source of light, they guess it’s from above because the sun is above. That’s the major source of light for us. If they see one person is much larger than any other, they assume he’s standing closer, in front of the other person. There are lots of clues that we take that are imperfect, but put them together and they give you 98-percent accuracy. That’s what gets us through life. The brain has evolved to make these very, very great guesses based on minimum information that turn out to be very effective.

In addition to that which is built into the brain, we have different life experiences, the top-down processes. We learn different things. We see different art. That acquired information—not built-in—also plays down on the brain when we look at a work of art. We compare one Jackson Pollock to another, or Jackson Pollock to de Kooning. That top-down information is acquired through our lifetime. And both of those approaches come to bear when we look at a work of art. Top-down information—our creativity, our imagination, our experiences with art—is particularly important in abstract art.

So what does the brain do when we look at a Vermeer painting versus if we, say, go look at a Dan Flavin installation?

Well, we don’t really know that. I’m starting to study that. We need to image the brain while people look at figurative art, transitional art, and abstract art by the same painter.

What are your expectations?

It’s possible that prefrontal cortical executive functions get recruited very dramatically when you look at abstract art, but we don’t really know that. It’s an imperative question that needs to be determined. I’m starting to work on it. I think it will take several years to make even the beginning of it.

One other possibility—that’s related to a general characteristic of sorts, that we use all the time but are unaware of—is something called “construal theory.” It pointed out that there’s a difference in the way we look at things that are nearby, compared to things that are far away; or things that are close in time versus others in distance in time. So for example, if I tell you I’m opening up a restaurant and I need to have bathroom facilities, for men and for women, and I’m opening up those bathroom facilities tomorrow, what sort of signage do you think I will need? You’re likely to say, you need to have an image of some sort that depicts ladies versus gentlemen. If I were to ask you the same question and say, these facilities I’m setting up are in a month from now, you would say just write down “ladies, gentleman.”

Similarly, if you do a painting—a figurative painting or an abstract painting—you would say, I’m going to take this painting and actually put it in a museum or in a gallery that’s across the street or five blocks away. If it’s figurative, you’ll say across the street; if it’s abstract you’re likely to say a couple of blocks away. It’s a way of thinking, which is quite general—as things become abstract or more vague, people put it in this category of being more distant in space and more distant in time.

And you’re the first to test this theory of neurologically processing abstract versus figurative art?

Yes. We are the first ones to test this in relationship to art. This is Daphna Shohamy, Celia Durkin, and I. What’s interesting is if this holds up it would indicate that there is a built-in logic in the brain that chooses between two ways of thinking.

Alois Riegl wrote that the history of art would die out if it didn’t become more scientific. Is he right?

I think he was a genius. He took art history from a completely descriptive field and tried to make it more empirical. He said you’ve got to align yourself with psychology and understand how the viewer responds to a work of art. This is really jazzed-up Ernst Kris, who pointed out that when you and I look at the same work of art we see it slightly differently. That means the viewer is undergoing a creative process that simulates—recapitulates in a very modest form—the creativity of the artist. That got Gombrich all excited, and it’s Gombrich who began to look into top-down and bottom-up processes. He read Bishop Berkeley, he read Helmholtz, and so Riegl started this whole empirical strain that I belong to, and anyone else who has worked in this area belonged to.

Cody Delistraty is a writer and historian based in Paris. He writes on books, culture, and interesting humans for places like The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and Aeon. Follow him on Twitter @Delistraty.

Watch: Anjan Chatterjee, author of The Aesthetic Brain, discusses the interplay between art and neuroscience.