One question for Julie Castillo-Rogez, a planetary geophysicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology where she focuses on, among other things, water-rich bodies like the dwarf planet Ceres and formulating, designing, and planning planetary missions.

Why do so many moons have oceans?

So many moons, and also Pluto and Ceres—bodies that don’t have a lot of heat. When you look at the evolution of thermal models starting from 20 years ago, when I entered the field, we were assuming that these bodies were pure water ice and rock. But then we realized that the materials that make up these moons can be very complex, and some of them can be insulating. There can be a lot of porosity, and maybe the water has impurities like ammonia and salts. All this contributes to maintaining and preserving oceans in these objects.

They’re actually very cold, but one of the main heat sources for icy moons and almost every object in the outer solar system is an isotope called aluminium-26. It’s an element that creates a lot of heat by decaying. It’s like uranium, for example, but it’s more efficient. It’s very short lived. So it acted only for up to 10 million years while the solar system was first forming. Aluminium-26 created so much heat that it melted the water ice in moons. Globally, they had very thick oceans. Most of the ice just melted, and then the water started freezing from the top.

It’s more difficult to find cold oceans.

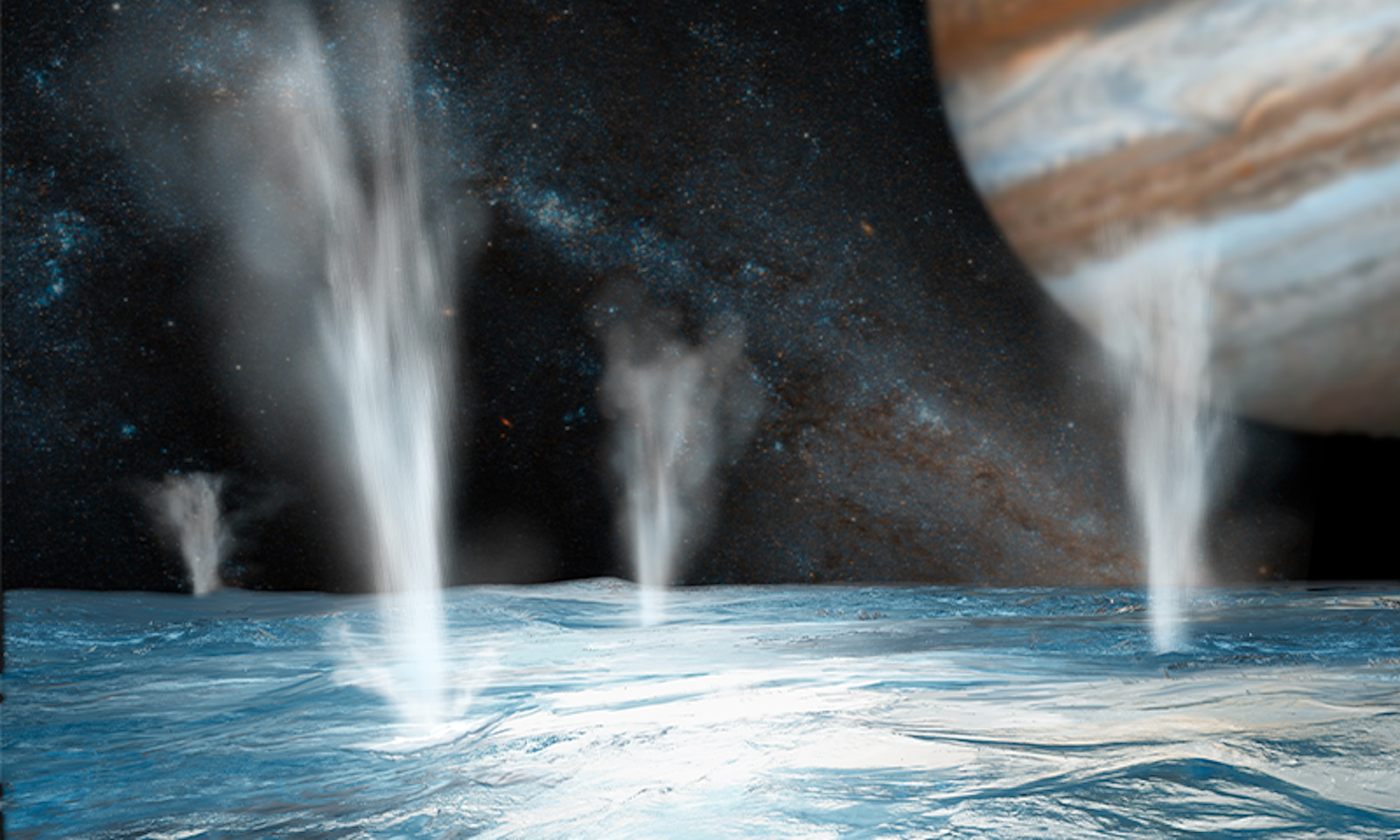

Our new research suggests that four out of five of Uranus’ largest moons—Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon—could also have oceans. We know there is not a lot of tidal heating in these moons caused by internal friction, a result of the gravitational pull of a planet stretching the moon as it comes close in its orbit. It’s now the main source of heat in the outer solar system. One of Jupiter’s moons, Europa, for example, has a lot of tidal heating. Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, is the same. But Uranus’ moons don’t have a lot of tidal heating. There’s actually 50 times less tidal heating in the Uranian moons compared to the Saturnian moons.

These results are based on modeling of internal evolution, present-day physical structures, and geochemical and geophysical signatures. We don’t have direct evidence. One of my coauthors, Richard Cartwright, has found ammonia on the surface of at least one of the moons, Ariel, and there might be ammonia on another one of these moons. This material is short lived, it’s not going to stay on the surface of the moons for a long time because it reacts with particles in space. So there might be evidence that there is ongoing exposure of material from Ariel. There’s also evidence on Ariel of recent geological activity, and that would favor the presence of a deep ocean at present.

What we can do with these models is help prepare a mission that will look to confirm these models. To look for deep oceans on moons, for example. So far the best technique has been to use a magnetometer to look for induced magnetic fields, like in Europa or Ganymede. But what we found is that these oceans that are predicted in the Uranian moons are actually very cold. It’s more difficult to find cold oceans. So we need to think about different techniques. NASA might look into a mission of this kind in the future to observe all of the large Uranian moons. We would have multiple flybys of Titania for sure, and maybe Oberon, Ariel, Umbriel. If the four large ones have deep oceans as predicted, then it confirms the idea that there are special circumstances, special materials, or special impurities that help preserve deep oceans in these moons. If they are frozen, it’s telling us that there is something else going on. So we still learn something from studying these bodies.

We are very hopeful that a mission could start within the decade. But it’s not clear if it’s going to be next year, or the next five years. It would take about 13 to 14 years to get to the moons. I’ll probably still be in the field when the mission starts, but I will probably be retired by the time it gets there. We’re talking about a launch after 2036. So an arrival at the end of the 2040s. A long journey. ![]()

Lead image: Jacques Dayan / Shutterstock