You could be forgiven for balking at the idea that our post-World War II reality represents a “Long Peace.” The phrase, given the prevalence of violent conflict worldwide, sounds more like how Obi-wan Kenobi might describe the period “before the dark times, before the Empire.”

And yet, the “Long Peace” has been a long-argued over hypothesis about the relative absence of major interstate conflict since 1945: Have mechanisms like nuclear deterrence, democratization, economic pacts, and international organizations like the United Nations really fostered an enduring trend of peaceful co-existence, or is this just a statistical fluke—a normal interlude of relative calm before another global-scale conflagration?

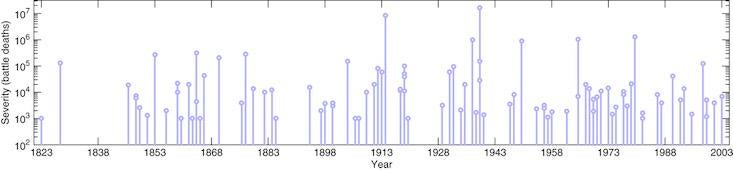

“This debate has been difficult to resolve because the evidence is not overwhelming, war is an inherently rare event, and there are multiple ways to formalize the notion of a trend,” Aaron Clauset, a computer scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, wrote in a paper last year. “Ultimately,” he goes on, “the question of identifying trends in war is inherently statistical.” Which is why he took a deep dive into the data collected by the Correlates of War Project; it has, among other things, information on the onset years and battle deaths (civilian casualties excluded) of 95 interstate conflicts between 1823 and 2003.

He came out with some intriguing calculations. In a section titled “The long view,” he says that, if we assume “the long peace does not reflect a fundamental shift in the production of large wars,” then we could estimate the “waiting time for a war of truly spectacular size”—one with a billion battle deaths (World War II, for comparison, had 16.6 million battle deaths). How long would we have to wait? The median forecast is 1,339 years, but the range of waiting times is super variable—there’s a 5 percent chance that such a catastrophic event would happen in under 400 years, and a 95 percent chance it would happen within the next 11,000 years.

Nautilus caught up with Clauset to discuss his findings.

Do you take a side in the debate about whether the “long peace” is an enduring trend?

I’m only willing to believe things that can be convincingly proved using hard-nosed statistics and data. In this case, the hypothesis that the long peace will stick is not on very firm statistical grounds. There are other people who are more optimistic, who believe in their hearts that the long peace will stick. That’s fine. They look at other sources of evidence on peace-promoting mechanisms—for instance, it’s been documented and shown very convincingly that the spread of democracy, the creation of peacetime alliances like NATO, the development of economic ties among nations, and the work of international organizations, like the UN, apparently have a role in reducing the risk of war. But in my analysis of this data, I think the evidential case for optimism is somewhat weak. The long peace may be more fragile than we have thought. We should not rest on our laurels. We have to maintain vigilance in order to make sure that the other processes, geopolitical or social processes that tend to unravel these peace-promoting mechanisms, don’t actually succeed.

Why do you think the evidence for the “long peace” is weak?

If you replay the statistics of the past 200 years, you would see periods of time that are as peaceful and at least as long as this long peace. This approach is what you would call a change-point analysis, because we know when we think something changed in the history of the production of wars. Can we tell a difference between the statistics on one side of that change-point from the statistics on the other side? Looking at the sizes of wars and then separately at the rate at which they’re produced, we don’t see any evidence of a change.

Are you optimistic or pessimistic about there being another big war soon?

I think of myself as an optimist. I look at the broader set of evidence, and I see that there are reasons to believe things are changing. The pattern appears consistent with an idea that there is a trend here—that the risk of a large war among some nations is going down in part because there has not been a large war on the European continent since World War II, a clear success of efforts to promote peace. But if those efforts really are having an impact, we may not know for a long time how big that impact is. There’s an upper bound on how big that impact can be as a result of the fact that we can’t tell conclusively that the statistics of war have really changed. The likelihood that any one of us individually will die in a war has gone down—that’s Steven Pinker’s basic thesis—but that doesn’t contradict the finding that the production-rate of wars at different sizes is stable. What makes things so interesting is that so much has changed in the world over this 200 year period. Public health. The world population. The number of nations. Technology has revolutionized everything. A wide variety of completely crazy geopolitical events have unfolded—plenty of nastiness in terms of nations becoming more autocratic along with nations being more democratic, et cetera. And yet, evidently the statistics of war have remained stable despite the changes in either direction. Why? I don’t know. I hope somebody else will look into this and tell me what the answer is.

Is there a way to know how much longer the “long peace” would have to last in order to call it a real trend?

We can generate a synthetic sequence of war events from a model that says that there’s no change between these two periods—1823 to 1945, and 1945 to now—and then ask whether or not the pattern that we observe in the postwar period is unusual with respect to this natural variation, the stationary model that we produced. This model represents what history says happens and how it should happen, which allows us to sort of replay history. The long peaces are relatively common statistical patterns under this model just because large wars are extremely rare. Because it’s fully specified, we can use that model to ask a question about the future: If that relative decrease in war were to stick around for a much larger period of time, how many more years would it need to hold before you could really say, yes, this postwar period is different from what we would expect from a stationary model where nothing’s changed. That’s where the number of 100-140 years comes out. At that point, we can then say definitively, by only looking at the severities and frequencies of wars, that the long peace is different. If you had a more sophisticated model that included information like where wars were fought, who was fighting in them, and why, et cetera, you could maybe shrink that number to some degree.

What does your analysis of war statistics say about the future?

Besides looking at the next 100 years, there’s the sort of, “Let’s take this argument to the logical conclusion and see what we can learn from it,” which is, “Let’s think about a huge event, like a billion battle deaths.” No one should use the likelihood of these events as predictions because they are, instead, mathematical calculations that are useful for probing our understanding—the billion-death population is useful because it allows us to think about the concept of stationarity. The statistics of war in the last 200 years appear to be very stable. If that’s true, is it plausible that that stability could extend backwards in time? Well, the billion battle-death calculation suggests that that cannot be true, because the distribution of how long you wait before you see a billion deaths includes a lot of human history. And we did not see an event that was that big during that part of the history. So it suggests that the rules of conflict have changed in human history, just not in the past 200 years. But if the rules of conflict are stable in the future, then it’s possible that a billion-death conflict could be generated by this stable war generating system. The plausibility of this forecast is unknowable. It may be that the mechanisms promoting peace, like peacetime alliances, economic ties, et cetera, really are having an impact. It’s just taking a long time for them to really show that they have an impact on the statistics of war—in which case, the likelihood of a billion-death war is actually much lower than the model would say.

What is the Correlates of War Project?

It is essentially one of the gold standard sources of data on violent conflicts, especially interstate wars. It has been put together by conflict researchers over many years. It’s high quality, low bias, low variance in terms of its coverage, so it’s essentially a fairly complete list of interstate wars that have happened during this time period. For the very early part of the time period, in the early 1800s, there’s some debate about what constitutes a nation as a member of the international system. But including or excluding those things doesn’t change the results that we have in this paper. It’s pretty easy to count dead bodies and to identify when wars start because we have formal and informal declarations of war—the Vietnam War is included.

Why didn’t you factor in civilian deaths in your analysis?

I did not look at those because that changes what we mean by war. Different kinds of wars have different kinds of civilian deaths versus battle deaths. So by focusing on just battle deaths alone I have a variable that is consistent across 200 years. It’s relatively consistently measured, even though things inside the wars themselves are changing, like the weapons and the likelihood of dying in a gun battle. It’s possible that if you had the technology of today for the wars of the 1800s, then they might have been bigger. I don’t know. They might have been smaller, too. It’s hard to figure out what that counterfactual would really be like.

Why do you focus on only interstate wars?

Interstate wars are special. Some civil wars turn into interstate wars, but it’s not that common. Focusing specifically on interstate wars alone gives us a relatively clean sense of a certain important class of conflicts, and it means that we are excluding things like civil wars. The American civil war is not in the data set. The statistics of civil war are currently being hotly debated inside the peace research community, in part because some evidence suggests that the rate of civil wars starting has been going up since the fall of the Soviet Union, and that there are countries that actually retract in a civil war cycle, in which they have a civil war and then there’s a period of peace and the civil wars start again. To get into the interstate war data set, it has to be a war between recognized members of the international system. For interstate-like conflicts, civil wars et cetera, it can be much messier. For instance, Iran’s funding of Hezbollah is an example of a state funding a non-state entity in a different country to carry out things that are like attacks. But in order to make sense of this incredibly complex system of human conflict, it can be useful to drill down deeply into one particular part, and this paper attempts to do that with the interstate wars.

Might there be something about war that makes it immune to our attempts to decrease its frequency?

Lewis Fry Richardson, a pioneer of mathematical techniques in weather forecasting who took an interest in the statistics of war very early in the 20th century, along with more recent researchers, argue that war—interstate wars especially—have a special kind of statistics in which they’re just rare. Especially the big ones. And, as a result, it’s difficult to convince yourself, if you just look at the statistics of the frequency and severity of these things, that the risk of large wars has actually gone down. Because if they don’t occur very often to begin with, then you might just get lucky.

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @BSGallagher.

This classic Facts So Romantic post was originally published in March 2018.