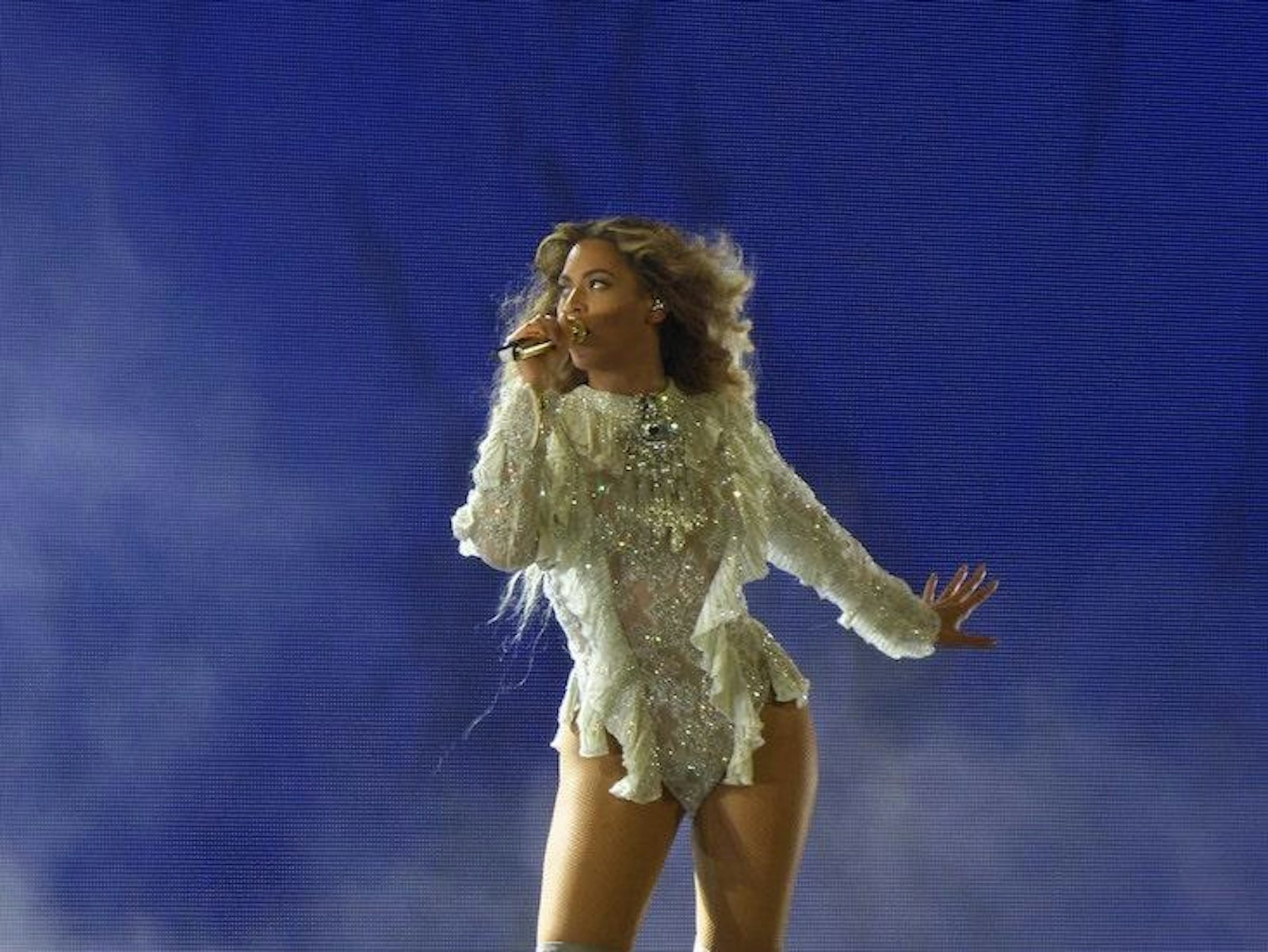

David Bowie and Beyoncé never shared a stage, but they share the distinction of having cleverly eponymous species names in their honor. Bowie, the British glam-rock and pop sensation, is immortalized in the name of a Malaysian huntsman spider, Heteropoda davidbowie. Beyoncé, the American R&B and pop singer who’s been as inescapable since the turn of the 21st century as Bowie was in his own heyday, is honored in the name of a horsefly. It’s one of five new species added to the Australian genus Scaptia in 2011 by Bryan Lessard and David Yeates. Only three specimens have ever been collected, and they sat unidentified in museum collections for decades before being recognized as distinct from their relatives, and new to science. Scaptia beyoncae is distinguished from other Scaptia species by its “conspicuous golden tomentum on tergite four onwards”—or less technically, by its rounded and golden derrière.

In explaining the name’s etymology, Lessard and Yeates said only that the “specific epithet is in honor of the performer Beyoncé.” News coverage, though, didn’t miss the implied reference to Beyoncé’s booty; she is, after all, well known for favoring golden couture that flaunts curves both fore and aft. Does this push at the boundaries of good taste? Perhaps; scientists have been known to push at those boundaries just like everyone else. But then, in the 2001 single “Bootylicious” (from Destiny’s Child, with Beyoncé as lead singer) she sang about her derrière with considerable enthusiasm. Scaptia beyoncae and its description, then, are presumably in agreement with the artist herself.

Why must scientific names, or anything else in science, be depersonalized, serious, nothing more than functional?

Of course, celebrity namings aren’t limited to musicians. Scientists have interests that span our world’s culture, both highbrow and low—as we have already seen in the story of the louse named for cartoonist Gary Larson, Strigiphilus garylarsoni. The television comedians Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert have a wasp and a spider, respectively (Aleiodes stewarti and Aptostichus stephencolberti). Athletes have species, too—for example, the wasp Diolcogaster ichiroi, for Ichiro Suzuki, who holds major league baseball’s all-time record for hits in a season (262). The fantasy novelist Terry Pratchett has a fossil sea turtle (Psephophorus terrypratchetti), which makes sense if you know that Pratchett’s novels are set on the Discworld, a flat planet resting on four giant elephants that stand in turn on a giant turtle swimming through interstellar space. Equally apropos, Herman Melville, who wrote about the great white whale Moby Dick, has a fossil sperm whale (Livyatan melvillei). Whether L. melvillei was white is not recorded in the fossil record, but it was certainly a great whale: It was twice the size of a modern killer whale and as large as any predator that has ever lived. (Melville would, one suspects, feel somewhat vindicated by all this, because the novel Moby Dick was a commercial failure, and during his lifetime critics considered him only a minor figure in American letters.)

Rudyard Kipling’s name lives on in a spider (Bagheera kiplingi), with a twist: Its name honors both Kipling and one of his characters (the black panther Bagheera who befriends Mowgli in The Jungle Book). The film actors Kate Winslet and Arnold Schwarzenegger both have ground beetles (Agra katewinsletae and Agra schwarzeneggeri; Schwarzenegger’s has suitably swollen biceps-like leg segments). Steven Spielberg has a pterosaur (Coloborhynchus spielbergi) and Pope John Paul II has a longhorn beetle (Aegomorphus wojtylai), and this may be the first time their names have occurred in the same sentence. The list goes on and on, with a new celebrity naming announced, it seems, every week.

Taxonomists (and other scientists) are divided about whether celebrity naming is a good idea. Some would like to reserve eponymous naming for scientists, arguing that whatever the merits of their music, Beyoncé and David Bowie (for example) have no connection to biology, so their names have no place in scientific nomenclature. Others take a stronger version of this position, holding that pop-culture celebrities simply don’t deserve the adulation they receive, no matter how that adulation might be expressed. To these people, modern society is already too obsessed with people who aren’t heroes but are simply doing their jobs—whether the job is hitting a baseball, making funny jokes, or pretending to be a time-traveling cyborg assassin (Schwarzenegger in the movie The Terminator, for those who have forgotten). Those holding either of these views wouldn’t suggest that scientists shouldn’t be fans of Beyoncé or Ichiro—only that they should keep that fandom separate from their science. But why should they? Why must scientific names, or anything else in science, be depersonalized, serious, nothing more than functional? Why shouldn’t scientists celebrate their passions—whatever those passions might be? Why can’t Scaptia beyoncae show us that scientific names can be golden, sometimes, rather than gray?

A second argument against names like Scaptia beyoncae holds that celebrity eponyms trivialize naming, making the science of species discovery and biosystematics seem like unimportant play in the public eye. This is plausible, I suppose, although the counterargument is that celebrity naming is one of a very few things that brings species discovery into the public eye at all. Beyoncé’s fly, for example, was written up in Rolling Stone, along with a beetle named for Roy Orbison, an isopod for Freddie Mercury, a roach for Jerry Garcia, a dinosaur for Mark Knopfler, and trilobites for Keith Richards, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, and all four Beatles. There’s some overlap, of course, between the readerships of Rolling Stone and the Australian Journal of Entomology; but not that much.

Bringing horseflies, and species discovery, into the public eye is something that matters. In our modern world, governments slash funding for universities, museums, and basic scientific research, and taxonomy consistently gets the shortest end of all the short funding sticks. The museums that hold biological specimens are sometimes so underfunded that they can’t keep their doors open, or protect their collections from disaster. In September 2018, the National Museum of Brazil was consumed by fire. Chronic underfunding played a major role in the loss—the museum, for example, lacked a functioning sprinkler system. Among the collections lost were 5 million insect specimens; among these specimens were, almost certainly, hundreds of new species waiting in their cabinets to be described and named. That’s what had happened to Scaptia beyoncae, in its own museum, and there’s nothing unusual at all about undescribed species in collections.

With any luck, in a few years we’ll all have forgotten who the Kardashians were.

Consider the case of Alexssandro Camargo’s new robberfly, currently awaiting publication of its name. In 2018, Camargo recognized a specimen in London’s Natural History Museum as representing a previously unknown species of the robberfly genus Ichneumolaphria. The specimen was collected in Brazil by Henry Walter Bates sometime during his 11-year collecting expedition there—an expedition that ended in 1859. The “new” Ichneumolaphria had spent 160 years, or perhaps a little more, in care of museum curators. It isn’t alone: For Camargo’s group of interest, robberflies of the New World tropics, the average “new” species has spent more than 50 years in a museum drawer somewhere. The typical voter, however, knows little about the collections departments of museums, which makes it very easy for governments to cut funding there instead of in more visible public services. The catastrophe of the Brazilian museum is, sadly, not unique: just two years earlier, the same thing had happened to the National Museum of Natural History in New Delhi, India. It would be foolish to think this can’t, or won’t, happen again; against that backdrop, it’s hard to criticize any effort to bring the science of taxonomy into the public eye.

A third criticism of celebrity naming is that it’s an unseemly publicity stunt on the part of the namer—or even nothing more than an attempt to meet the eponymous celebrity. Could a taxonomist really think this might work? And might it? Frank Zappa (the experimental, and indescribable, musician) has at least five species named after him: a spider (Pachygnatha zappa), a mudskipper fish (Zappa confluentus), a fossil snail (Amaurotoma zappa), an enigmatic, so-far-unassignable fossil animal (Spygoria zappania), and a jellyfish (Phialella zappai). The namer of the last species, at least, did in fact have a cunning plan to meet Zappa. Ferdinando Boero, an Italian marine biologist, tells the story of heading to the Bodega Marine Laboratory in California to study jellyfish. Boero knew the eastern Pacific jellyfish fauna was poorly known, and he explained: “I would find some new species for sure. Once I had found them, I would have to give them . . . name[s]. I would dedicate one of them to Frank Zappa; I would tell him about it; he would invite me for a visit.”

Quite likely to Boero’s surprise, the plan worked. He wrote to Zappa about the planned naming, and received a return letter from Zappa’s wife, Gail, reporting Frank’s reaction: “There’s nothing I’d like better than having a jellyfish named after me.” The letter came with an invitation for Boero to visit Zappa at his home—which turned out to be the first of many visits over a long friendship. Zappa even dedicated his very last concert, in Genoa in 1988, to Boero, and sang a song about him. Does any of this make Boero’s naming somehow disrespectful, or trivializing, of science? Was some damage done to taxonomy or invertebrate zoology? It’s hard to see how. P. zappai needed a name, and it got one; Zappa has one more small legacy on Earth; and Boero has a story to tell. There’s even a suggestion here, in Zappa’s reaction to the idea, that people outside science can indeed be aware of the significance of a newly discovered species and the honor represented by its naming. That’s an encouraging thing for the science of species discovery.

Some of the celebrities honored in species names are likely to have lasting fame, while others may ultimately prove to have been flashes in the pan. And that brings me to the final objection to scientists’ indulgence in celebrity naming: that many such names are doomed to obscurity and etymological unhelpfulness. After all, with any luck, in a few years we’ll all have forgotten who the Kardashians were. But surely the argument about the ephemeral nature of celebrity applies just as much to names in honor of anybody else. We already have thousands of species named for people who are now obscure. At worst, these names become arbitrary: not one entomologist in a thousand knows which Smith the mosquito Wyeomyia smithii celebrates. At best, these names become maps to hidden treasure, rewarding those who follow the trail of clues with stories of fascinating people and human history.

Perhaps in 100 years, someone will catch and identify Jon Stewart’s wasp, and end up mystified by the bizarre 21st-century history that fed The Daily Show. Perhaps curiosity about Heteropoda davidbowie will lead someone to rediscover the music of David Bowie. Or perhaps a museum will mount a new fossil of the pterosaur Coloborhynchus spielbergi, and a search through some 22nd-century descendent of Netflix will lead someone from Jaws to Raiders of the Lost Ark to The Color Purple and Schindler’s List. That’s a journey that will always be worth taking.

Stephen Heard directs the Heard Lab at the University of New Brunswick, which seeks to understand the ecology and evolution of biodiversity. His new book, Charles Darwin’s Barnacle and David Bowie’s Spider: How Scientific Names Celebrate Adventurers, Heroes, and Even a Few Scoundrels, from which this piece is excerpted, will be released in March 2020.