Marine geophysicist Raquel Negrete-Aranda knows her field lacks a certain whiz-bang appeal. An ocean heat-flow model just can’t compete with the images of bright-red Oasisia alvinae tubeworms swaying around a hydrothermal vent field two miles below the surface in the Gulf of California. But the ocean’s “plumbing” can tell us a great deal about how life thrives under such extreme conditions, and there are few people on the planet who understand this plumbing like Negrete-Aranda.

Negrete-Aranda’s expertise is in the thin layer of crust on the floor of the ocean—if the Earth was an avocado, the crust would be its skin, she says—and this layer tells us a lot about not only life at the bottom of the ocean, but also how the Earth’s continents evolved and why Arizona may one day boast oceanfront property (though not for many millions of years, if you are thinking of investing).

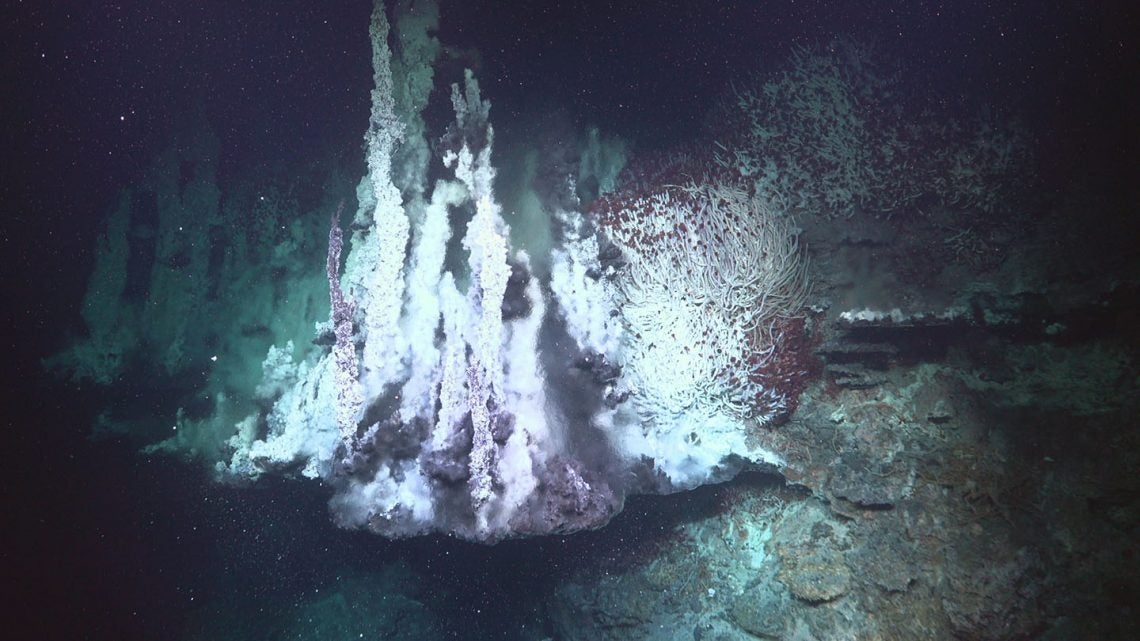

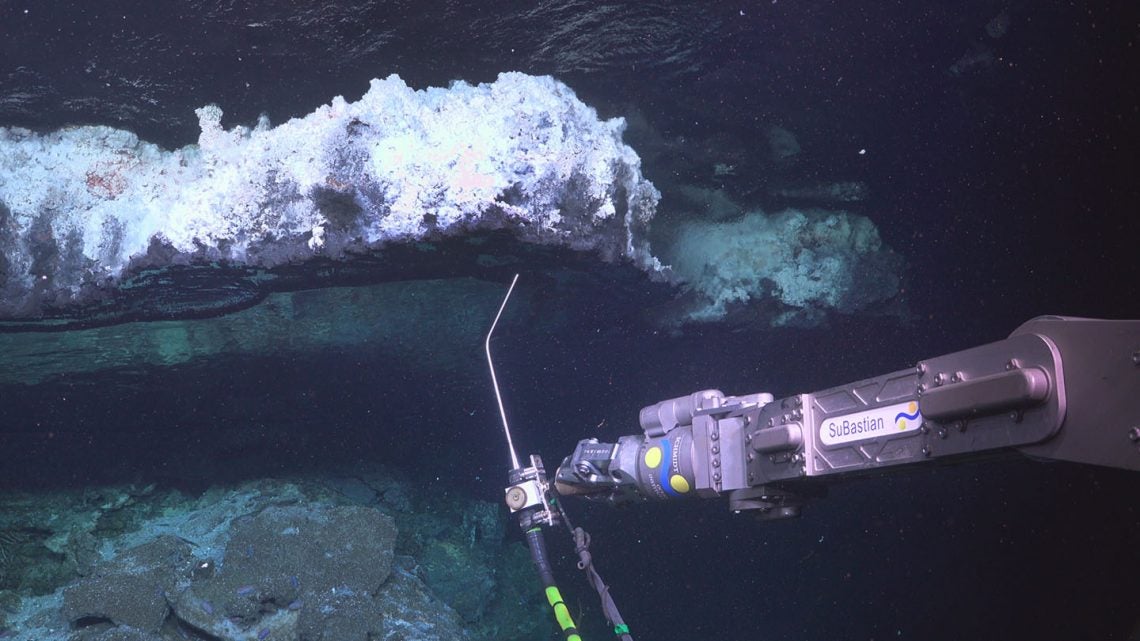

As a researcher at Mexico’s Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education at Ensenada, Negrete-Aranda has been instrumental in leading deep-sea expeditions around the world, notably one last September aboard Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Falkor research vessel. There, she was part of a multi-disciplinary team that explored never-before-seen hydrothermal vents in a region called the Pescadero Basin in the Gulf of California. Biologists and geologists used remotely operated vehicles to explore the vent, with the hopes of tracing the origins of the basin’s superheated waters. Working together, the team discovered at least six new species around vents spewing water as hot as 549 degrees Fahrenheit.

This interdisciplinary approach helped each of us to better understand our own work.

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing. From sexism to “reverse” sea sickness, Negrete-Aranda has navigated more than Earth’s crust while in the field. But she prides herself on perseverance in the face of many obstacles, and on her efforts to make the field more accessible to other female scientists.

Nautilus spoke with Negrete-Aranda about her recent Falkor expedition, challenges as a woman in science, and the incredible discoveries being made in the Gulf of California.

You just completed a month-long expedition to the Pescadero Basin in the Gulf of California, and in the process you and the rest of the team discovered new hydrothermal vents and several new animal species. Why did you want to study this part of the ocean floor?

Before 2012, when the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute led an expedition to the Gulf, we knew very little about the Pescadero Basin. We knew a lot more about the Guaymas Basin, located northwest of the Pescadero Basin, because of seismic activity there. Same with the Alarcon Basin, at the southern tip of the Gulf, because Alacon was the first basin in the Gulf to offer evidence that the seafloor is pulling apart. The discovery of hydrothermal vent fields in Pescadero was a big deal, as the only other vent fields that were known in the Gulf were the ones in Guaymas, and they are the typical black smokers. They are pretty scarce too—nothing like the diversity or the scale of the vents in Pescadero.

All the basins in the Gulf of California are interconnected, but what happens in the south and in the center of the Gulf is very different from what’s going on in the north. That’s why researchers think of the Gulf as a big natural lab, where you can explore many different aspects of rift evolution and basin evolution.

You devoted the first leg of your expedition to mapping the Pescadero Basin floor. A lot of people don’t know how important mapping is, but it’s kind of equivalent to exploring an unknown continent, right? It’s super time-intensive, challenging, and takes a lot of energy and resources to do it well. What have you learned from mapping this region?

Completing the mapping was very important, because it served as the layout for everything we did on the rest of the expedition. And now we have really good maps of the Pescadero Basin. Using the maps, we found very interesting things in terms of the evolution of the northern part of that basin, and some evidence of seafloor spreading there. And then on the heat flow side, we were very interested in understanding the plumbing of the hydrothermal vent systems. It’s very complicated—you think there must be a heat source somewhere down there that’s feeding the vent fields at the bottom of the ocean, but without looking deeper, you don’t have much sense for the sub-bottom profiles of the faults.

Can you talk about the significance of heat flow around hydrothermal vents? What does it tell you about what’s happening below the ocean floor?

Heat flow, which is the movement of heat, or energy, from the interior of Earth to the surface, gives you a sense of the thermal state of a general area. You have to do heat flow measurements in a systematic way—it doesn’t really serve any purpose to take one measurement here and another measurement there and just have a bunch of scattered measurements that don’t say anything important about the whole system. But in general, the heat flow is very high here. At the end of the day, we found that the faults are the primary paths for the hot fluids being produced down below to come back up to the surface.

Water is going down into the faults and then coming back up?

Yep. You have a kind of recharge system. Especially in places like Pescadero, where you have thick sediment coverage on the ocean floor, hot fluids can only go up through small fractures in the crust. From a thermal point of view, it really impacts the way hydrothermal systems work in general. It tells you about the story of the basin and the regional processes at play.

What does it all look like? If I were to take a submarine down, what would I see?

As long as you have this active venting, then you will have these amazing chimney-like structures. In Pescadero, the fluid is very rich with minerals. It’s beautiful, actually. Usually with the black smokers, the fluids are very, very dark, like smoke. But here, it’s just very, very, clear, and it’s also very, very hot. The hottest one that we measured, in terms of fluids coming out of a vent, was about 549 degrees Fahrenheit.

Some of the vent fields in Pescadero also have a very particular chemistry. And that’s where you start connecting the dots: you have the very particular chemistry, and then you have these communities of microbes and animals that are very specific to this area. I think the team discovered six new species of worms on this one expedition. And this interdisciplinary approach helped each of us to better understand our own work.

Right! Biologists will know if they see clams, that this might be an interesting spot, geologically speaking. And that’s not something you’d know if both parties hadn’t been on the ship.

Exactly. I’m very happy that the other researchers are starting to understand the importance of doing heat flow measurements. Mapping heat flows might sound pretty boring, in the sense of like, well, it’s much more exciting to see new species, all the unique and beautiful ecology and microbiology! It’s like you’re looking at like another planet, while gaining insight into these organisms and how they thrive so deep in the ocean. But heat flow can help biologists to better understand why certain animal communities live where they do. This multidisciplinary approach helps everyone understand things better. I know if the microbiologists were working alone, or the marine geologists were working alone, the expedition wouldn’t have worked as well as it did.

The team discovered six new species of worms on this one expedition.

To be honest, I had no idea there were hydrothermal vents in the Gulf of California. I thought vents occur in areas where tectonic plates are either moving apart or crashing together. What’s happening here?

The Gulf of California is a very unique place. Twenty million years ago, there was active subduction with the North America Plate and the Pacific Plate, with the Pacific Ocean crust sliding under the continent. We still have active subduction zones in central Mexico—which is why we have so many earthquakes in Mexico City—but up north, the subduction stopped around 12 million years ago. So the tectonic boundary changed: North America started moving south, and the Pacific started moving north, and they were just sliding by each other. But at some point, that angle started to change slightly, so it’s sliding but also widening.

And that’s exactly what happened between the Baja Peninsula and mainland Mexico. Baja just jumped on the Pacific Plate, and so you had the start of the opening of the Gulf of California around 6 million years ago. So that’s an ongoing process, of course. The Gulf of California will grow bigger and bigger, and at some point, the peninsula will be completely ripped apart from the Mexican mainland.

I always thought people were joking when they said California was eventually going to fall off into the Pacific. But I guess there’s some truth to that.

Don’t worry. It’s going to take a very, very long time to get there.

Let’s talk a bit about what it’s like to be a woman in this field. For example, some old deck hands still think it’s bad luck to even have us on a boat.

You know, I could not believe it, but it’s true. Not on every boat, but yeah, it still happens. On one of my first expeditions, we went to the northern Gulf of California to do some heat flows, and I was the only female scientist on crew. Since the beginning, I’d felt this weird vibe from the captain, though the rest of the crew was very friendly. But at some point, somebody mentioned him, and I said that the captain is very nice with everybody else but he’s very formal with me, and that person said, “You might not be aware of it, but women are considered bad luck when they’re on a ship.”

Wow. I’ve also heard these stories. Unfortunately, they are fairly common.

This is an ongoing issue for many women in ocean science, but I made a decision a long time ago that I wouldn’t let that stop me in any way. It’s been a learning process, though. At the beginning, I took things very personally.

Do you feel that these Schmidt expeditions are valuable for your younger female students? We talk about these expeditions being a service to science, of course, but not so much as a service to culture or to women scientists in general.

Oh, absolutely. I have three female students in my lab, and they went with me on this last expedition on the Falkor, and they were super, super excited about it. Schmidt is unique with their approach to research. For a young scientist, it’s really empowering to participate in one of these expeditions, because you get to work with state-of-the-art technology in a very nice setting with very nice people. My students came back empowered and very motivated. I think I’m doing my job in that sense, and I’m very proud of that.

Heat flow can help biologists to better understand why certain animal communities live where they do.

Do you ever have other challenges at sea? Do you get seasick?

I have a very bad vestibular system. I don’t normally get seasick but I get sick when I come back to land.

Yes! I get that too sometimes. What do you call that in Spanish? In English, it’s called “dock rock.”

Mal da tierra! Or “evil earth.” It’s like being seasick when you’re at home. Your brain still believes you’re still on the ship. But now I think I have found the right combination of drugs to help me.

I feel like everybody thinks that if you’re an oceanographer, biologist, geologist, or whatever, and you go to sea, you must be impervious to these things. And that’s never been true for me. I get so seasick. There’s usually a small group of us all hanging over the side of the ship together.

It’s something that happens to even the most seasoned sailors. Going to sea is actually very exciting, but it’s very tiring as well, because you’re in expedition mode, then you’re working almost 24/7. It’s hard, but it’s very exciting too.

This last trip you took, it was on the Falkor, right?

Yes. It was the final expedition for the original Falkor! They bought a bigger ship with more infrastructure, called Falkor (too). But if it’s any consolation, this expedition was a very successful one.

So what do you want to do next?

I definitely want to take Falkor (too) to the northern Gulf. I’m just dying to see what’s down there with the ROV. We have a very thorough heat-flow profile, and we’ve found very promising geothermal prospects. The basin is so shallow, only 650 feet of water column. And it’s so hot you cannot believe it.

Do you think you’ll find a vent? Or maybe a seep field?

Yeah, maybe even a mud volcano, I don’t know! Something is going on down there. One of the main geologic faults goes right into the northern Gulf, and this area sits right on the southern tip of that fault. So it wouldn’t be that surprising to find a geothermal field there too. The geothermal prospects could be amazing. I would love to go to the northern Gulf to try and resolve some of these mysteries.

Lead image: Raquel Negrete-Aranda in the Falkor control room during a dive in the Pescadero Basin. Photo by Schmidt Ocean Institute.