When I first gave up my running shoes for a road racing bike in 2016, I was confronted by a scroll of unspoken rules I would be expected to follow if I were to be taken seriously as a congregant in the Church of Cycling.

The edicts were compiled by the Velominati—an anonymous cycling cognoscenti that presents them as holy writ. Cycling shorts must always be black, though socks can be any color you like. The color of your saddle, however, must match the color of your handlebar tape and tires without exception. Which is to say, these, too, must always be black because tires only come in one color. And so it was for pre-ride coffees: black only, preferably espresso. Anything dulled by milk was purely for the unsaved.

Who was I to disagree? It was a demand of my new culture. I bought a razor and shaved my legs.

There were others. Never, under any circumstances, lift your bike over your head—it is undignified for the machine. If you are ever unfortunate enough to draw the number 13 at a race, it must be pinned to your jersey upside down. And speaking of bad luck, accidents are not to be spoken of unless they involved a visit to the emergency room. Road rash, scraped elbows, bruised hips, and other evidence of unexpectedly meeting the pavement are just part of the discipline.

Some rules were intuitive, like showing up for training rides on time because they start exactly when they are supposed to—and I have never known that not to be the case. Others were more bizarre, such as never putting a bike on a car’s roof rack unless the bike is worth more than the car—and you might be surprised at how often that is the case.

Helpfully, these rules were emailed to me by my first serious riding companion, a multi-time state champ who took his coffee black, drove a $19,000 Volkswagen, and dragged me for months along rural roads until I was strong enough to compete in our city’s weekend group rides.

Clearly, he told me, some of the rules are open to interpretation and convenience. But there is one that is not: Shave your legs.

There were no exceptions. Even the flamboyant Peter Sagan, then the world’s most revered cyclist, was once chastised by the elder brethren of the sport for having the nerve to turn up at a race au naturel.

Who was I to disagree? It was a demand of my new culture. I bought a razor and have been shaving my legs ever since.

As the summer tradition of the Tour de France once again descends upon us, a few hundred million devotees of the sport will watch, parse, argue about, and rejoice over the frenetic three-week-long procession that’s powered by some of the smoothest male legs on Earth.

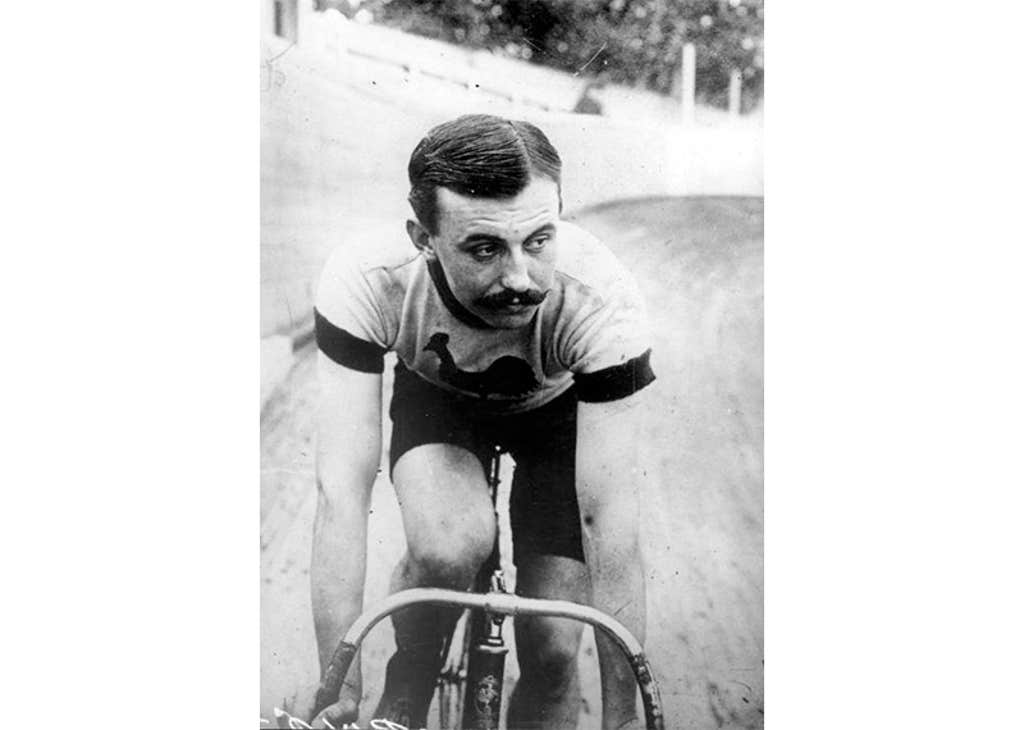

But why, since the Tour began in 1903, have its participants shaved their legs? A matter of hygiene? An offering to the velo gods? Is it purely a question of peer pressure, guided by fear of wrath from the fussy deities on cycling’s Mount Olympus? Or is there something more earthbound behind it—some matter of utility that the great grandfathers of le cyclisme suspected long ago but couldn’t quite articulate as they first dragged a razor up their shins?

As it turns out, there is. Shaven legs are much, much faster. It just took until this century to prove it.

In 2012, as a recently minted graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with a degree in mechanical engineering, Marc Cote came to Specialized, a dominant manufacturer of high-end bikes headquartered in California. Cote had a hypothesis: bicycle frames, wheels, helmets, jerseys, shorts, and shoes were all conspiring to cost elite cyclists valuable seconds in aerodynamic drag.

Aerodynamic drag, Cote explained to me in a recent chat, consists of two forces—air pressure drag and direct friction (known also as surface friction or skin friction). Direct friction is the force that occurs when wind meets the surface of rider and bike, but is nearly insignificant at the comparatively low speeds a cyclist travels. However, it is critical to consider when designing, say, an airplane.

On the bike, air pressure drag is the main beast. A cyclist and his machine form a blunt (“bluff” in aero lingo) shape forcing the air to separate around them as they move forward. The harder the cyclist pedals, the more the air in front of him is compressed, meaning that the harder he pushes forward to overcome this resistance, the harder the air pushes back.

Once the air grudgingly parts around the rider, the battle is not over. As the rider moves forward, battering the air out of the way, the air behind him becomes less dense, forming a low-pressure zone, or vacuum, that literally sucks him backward. This is a formidable force. In fact, on a flat road, aerodynamic drag is by far the biggest obstacle to a cyclist’s speed, accounting for 70 to 90 percent of the resistance felt when pedaling.

Reducing the surface area of the cyclist as he confronts the wind is therefore key. The more streamlined the design of an object, the easier it is for the air to close around it, thereby approaching the holy grail of aerodynamic design: laminar flow—that sublime moment when the air closes around a moving object without leaving a turbulent wake.

As there is little that can be done about the awkward shape of the human body—though it must be noted that most pro cyclists are tall and willowy and in constant battle with their weight—the design of the bike and the equipment the rider wears are critical to speed. The less that is flapping about in the wind, the smaller the surface area of cyclist and bike.

The Tour de France is one of the hardest tests of endurance that humanity has sadistically invented for itself.

This was an issue that the titans of yore hadn’t much considered as they pulled their baggy woolen jerseys over their heads. In the 1968 volume King of Sports: Cycle Road Racing, envisioned by its author as the final word on training, British cyclist Peter Ward argued for comfort over style. Clothing that is “the least bit tight or restrictive” should be avoided, he wrote. Cycling shorts, he added, should be held up with “braces,”—British for suspenders—and be “slack and comfortable.”

A few years later, in 1976, the Dutch pro cycling team TI–Raleigh ignored that advice and brought Lycra to the cycling mainstream. There hasn’t been a need for suspenders since. Over the following decades, the fit of cycling apparel has moved steadily skin-ward, cementing the image of the spandex-clad road warrior in the popular imagination. But Cote still suspected that there were a few wrinkles yet to iron out.

By 2013, he and his colleague Chris Yu in the aerodynamic research and development department had cajoled their bosses at Specialized into taking an enormous and cost-intensive leap—building a multimillion-dollar cycling-specific wind tunnel to track down and eliminate those last little bits of turbulence in the quest for a faster ride. The results were—and continue to be—transformative.

Research in cycling aerodynamics—what Cote calls “the invisible science”—has led to helmets that make the head of the wearer look like it has collided with a flying saucer, and shorts and jerseys that are so tight that it takes imagination not to see the more subtle curves of the flesh. The clunky shoes of Ward’s era have shed their laces for shrewder and smoother fasteners that don’t cause the air to hiccup around them. Even socks can be woven in special configurations that reduce drag. And new techniques in molding carbon fiber—the lightweight DNA of modern race bicycle-making—has produced frames that would have been unrecognizable as recently as 2007, when Lance Armstrong and his U.S. Postal team were still riding what amounted to a collection of fused-together cylinders.

Nonetheless, all the technological advantages can’t conquer the inevitable human bulk of the rider, who constitutes about 75 percent of the aerodynamic drag that cyclist-plus-bike must overcome. And that’s where Cote’s most surprising research comes in.

It began with Jesse Thomas, a Specialized-sponsored pro triathlete who dropped by Cote’s wind tunnel in 2014 to dial in his equipment before an upcoming Ironman competition. He, Cote, and Yu ran through different experiments—one comparing wheels, another tires, yet another helmets and skin suits—and chose those that the tunnel data said caused the least amount of drag. Ironman races include a 112-mile bike ride wedged between a 2.4-mile swim and a marathon, so any seconds Thomas could massage out of his equipment would be critical.

Thomas had turned up that day much the way Peter Sagan had at that race in 2016, sporting a full shag up his calves and thighs, though neither he nor Cote had put much stock in that until after completing the tests.

So as more of a gag than anything else, he and Cote thought they would solve the age-old riddle posed by the ancients once and for all: Does shaving your legs make any difference at all? Thomas sheared his guns to see.

The first set of results caused Cote’s jaw to drop. If the data were correct, Thomas could save 70 seconds for every 24.6 miles (or 40 kilometers, a standard time trial distance) he rode on the bike. This was an enormous time gain in a field of sports where victory is often decided by fractions of seconds and tenths of inches over a finish line.

So they tested Thomas again. And again. And the numbers kept showing the same thing.

It was a Eureka moment.

Over the next several weeks, Cote and Yu invited more of their cyclist and triathlete friends to come and test hairy, shave, and test again, developing along the way what they called a “Chewbacca scale”—a rating of 1 being a leg with relatively little natural hair all the way to 10, connoting a level of hirsuteness rivaling Hans Solo’s simian sidekick.

Time savings varied slightly depending on where test subjects fell on that scale, but the results continued in each case to be profoundly faster—so much so that it seemed silly for any performance-minded cyclist to forgo shaving. This was the very definition of free speed.

What was remarkable here, said Cote, was this: Most prior work in aerodynamics had been conducted at much higher speeds and the results of those experiments implied that hairy legs might benefit cyclists, the bristly hair acting much like the aerodynamic dimples on a golf ball.

Those characteristic dimples create a thin, turbulent boundary layer of air that clings to the ball’s surface. This allows the smoothly flowing air passing around it to follow the ball’s surface a little farther around the back side of the ball, thereby decreasing the size of the ball’s wake. This reduces turbulence behind it and lessens the area of that low-pressure zone that follows and sucks at cyclists.

But a golf ball driven by a PGA player can travel as fast as 168 miles per hour—far faster than the aspirations of even Tour cyclists. At average speeds between 20 and 40 miles per hour, the bigger factor for cyclists was the surface area of the body meeting the wind—and the surface area of a shaved leg is as much as 10 percent less than that of a hairy counterpart.

“At these speeds, reducing the surface area is the most important thing, and that surprised us,” Cote told me. “Past studies assumed that hair would be insignificant or would work like those divots on the golf ball—but at cycling speeds it just adds to surface area.” Cote determined shaved legs are the second most important aerodynamic adaptation a cyclist can make, the first being whether the rider choses to wear a skin suit—which, with its long sleeves, also covers the hair on the forearms.

Cote’s results were never compiled and published in a scientific journal, but his and Yu’s work has been quasi-peer reviewed by countless imitators, most recently this May by the Global Cycling Network, one of YouTube’s most watched and slickly produced biking-dedicated channels. In fact, GCN has visited the topic at least five times since Cote uploaded his original videos. And each time, the results showed the same thing: Cyclists with shaved legs are faster.

Le Grand Boucle, or Big Loop, as the Tour de France is nicknamed, is the grandest of the grand tours, drawing a viewership on television and in person along France’s winding country roads and mountain switchbacks that dwarfs the Super Bowl. By all accounts, it is one of the hardest tests of endurance that humanity has sadistically invented for itself.

The Tour is also the grandest performance of cycling aerodynamics at work. The Tour de France is ridden by 12 teams and consists of four kinds of stages—flat stages, hilly stages, mountain stages, and time trials, which, confusingly, are ridden on different sorts of bikes and require different styles of riding.

For the first three, riders mount the more familiar-looking road bike, with its ram’s horn handlebars, and race together as a peloton, the first man over the finish line claiming victory. The time trials—of which a typical Tour only has one or two—are when each of the 198 riders are sent out on a course alone to race against the clock.

And it is on time trial bikes that the invisible science has had the most visible impact. Often resembling a wing turned sideways, riders mount these bikes dressed in skin suits, a torso hugging, long-sleeved singlet with low profile stitching. They then hunch over their machines with their elbows perched on aero bars, their arms held before them in the style of a praying mantis. Then they tuck their heads, capped in those absurd turbulence-reducing helmets, and go—each grain of sand through the hourglass a strike against them.

All the technological advantages can’t conquer the inevitable human bulk of the rider.

Road bikes, too, have evolved with the quest for aero. Round tubes have flattened out on their backsides and their leading edges have sharpened so that they pierce the air like a bullet. Seat posts are oval or teardrop-shaped and handlebars are flat in profile across the top and taper to an edge along the backside mimicking a wing. And deep-rimmed carbon wheels have long since replaced their skinny air-stirring aluminum alloy counterparts and offer yet further wind-rending advantages.

When the cyclists are on their road bikes racing in a peloton they take advantage of the aero modification as old as cycling itself—drafting. It is this technique that allows cyclists to capitalize on the turbulent low-pressure zones left by the cyclist riding immediately ahead of them. The low pressure behind the leading cyclist will help pull the following cyclist forward, while the vortices produced by the lead cyclist’s wake will also swirl around the following cyclist and push him forward. So significant is the effect of drafting that cyclists who are riding in a group can save up to 40 percent in energy expenditure over a cyclist who is riding solo. Anyone who has ever cast their gaze skyward at a flock of migrating birds has seen aerodynamic drafting in action.

On the ground, the technique is most apparent in the so-called lead-out trains preceding the final sprints in the Tour’s flat stages. In these chaotic charges, it’s easy to spot the jerseys of each team forming monochromatic lines as they weave through the peloton.

The idea is that several team members will burrow through the air for their designated sprinter, who sits on their wheels as the riders in front of him provide a wake full of those helpful vacuums and eddies. One by one, the leading riders will take a turn at the front and dig as deep as they can, ratcheting up the speed before they peel off to the side, exhausted. Finally, the last leading rider will pull off, launching the sprinter at breakneck speed a few dozen meters from the finish line. But each of these trains must have a highly aerodynamic engine for the sprinter to have any hope at all.

The evolution of all this air-slicing technology is reflected in the average speed of the Tour itself, which has spiraled upward since the early days. Two-time victor Firmin Lambot of Belgium posted the slowest average speed in the 1919 Tour at 14.97 miles per hour. One hundred and four years later, Denmark’s Jonas Vingegaard nearly doubled that in his 2022 Tour victory with an average speed of 26.1 miles per hour—all while having traversed 122,000 feet—more than four times the height of Mount Everest.

The work of Cote—who now works at Zwift, a virtual cycling app—and his copycats provides valuable data for amateur cyclists like me, who typically don’t possess the deep pockets and sponsorship deals that a professional cycling team does, but nonetheless obsess over aero, take on debt to finance new bikes, race and go on training rides. A 90-cent razor, Cote told me, might be the wisest investment I can make.

But in a sense, Cote’s test results simply validate something that most serious cyclists will—out of superstition or a sense of deference or dogged adherence to the commandments of the Velominati—continue to do anyway, regardless of what the wind tunnel says.

Grasping for these seemingly insignificant advantages was something that the cycling gods of the past understood acutely. At the center of their logic was a simple truth: Whatever you think makes you faster probably does.

Fausto Coppi, the Italian cycling giant who dominated the Tour in the years following World War II, insisted that he be carried upstairs to his hotel rooms after every stage of the race to preserve the strength of his legs.

France’s great Roger Rivière, considered the favorite for the 1960 Tour until he careened over a guardrail in the mountains on stage 14 in an accident that left him crippled, was known to inflate his tires with helium.

His countryman, the towering time trialist Jacques Anquetil, who claimed three Tour victories in the late 1950s and early ’60s, used to take his water bottle off the cage on the frame of his steel Gitane rig and tuck it into his jersey pocket when confronted with a climb. (Another finding by Cote: you will shave off 38 seconds if you tuck your water bottle in the back pocket of your jersey instead of the bottle cage on the frame.)

And so the story goes, right through the calamitous drug scandals of the Lance Armstrong era, where Armstrong and much of his team—and indeed much of the peloton—blood-doped with human growth hormone to goose their performance.

But even in the years since the sport has cleaned up, there remains that search for a talisman, for the ineffable edge that will express itself at exactly the right moment and inch you over the finish line first. To acclimatize his respiratory system to the Tour’s high mountain stages, German rider Tony Martin—who won numerous Tour stages but never the coveted general classification overall win—had his entire house converted into an altitude chamber.

Against such tactics, shaving your legs is the least you can do.

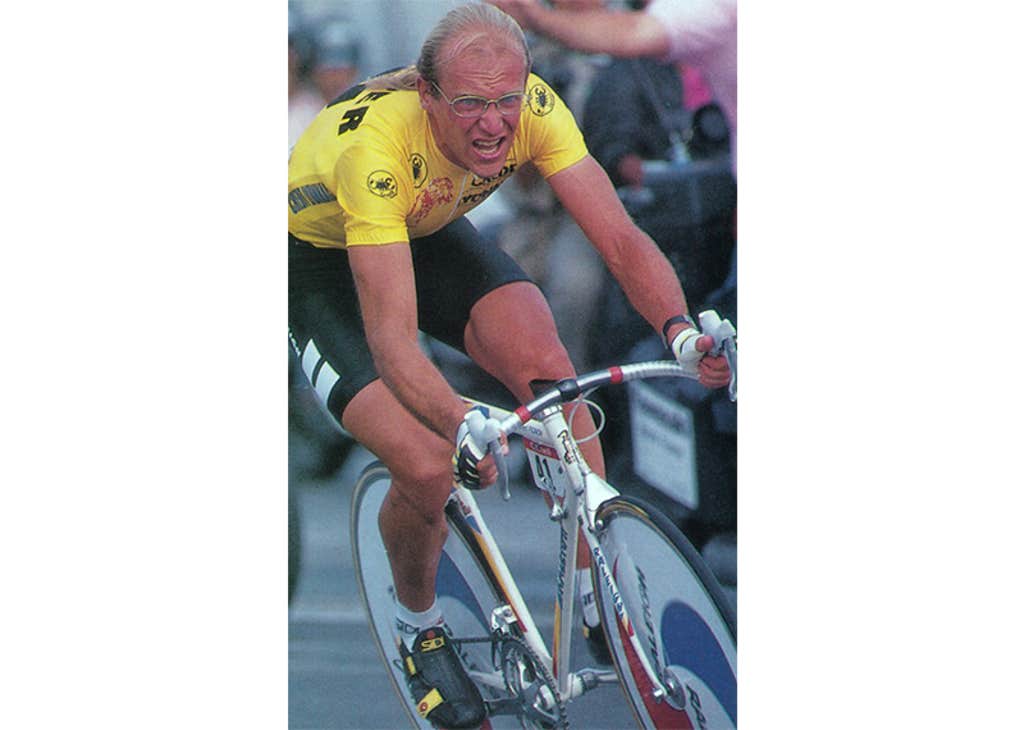

Because in the oral histories of cycling, passed down to me by the riders who taught me how to take my coffee, tales of losing by a hair are almost too painful to recount—such as when the US cyclist Greg LeMond beat the Parisian powerhouse Laurent Fignon in the 1989 Tour’s final time trial stage, giving LeMond the overall victory by a mere eight seconds—the closest margin in Tour de France history.

It was an age before wearing helmets in the Tour became compulsory and Fignon’s biggest enemy that day was not LeMond. It was his signature blond ponytail.

Cote and Yu tested it. They took a cyclist of Fignon’s stature, put him and a bike in the tunnel, bent him into Fignon’s tucked time trialing position, and topped him off with a wig that matched Fignon’s flowing tied-back locks.

They turned on the wind. Then stopped it, cut off the ponytail, and tested again. The result?

“Fignon should have gotten a haircut,” Cote said. According to the data, Fignon would have beat LeMond by four seconds had his ponytail not been flapping about in the wind, causing critical aerodynamic drag.

“You never stop grieving over an event like that,” Fignon bitterly wrote in his 2010 autobiography.

Ever since I heard that story, I have started shaving my head, too. ![]()

Charles Digges is an environmental journalist and researcher who edits Bellona.org, the website of the Norwegian environmental group Bellona. He is also an amateur cyclist and owns too many aero-optimized bikes.

Lead image: Studio77 FX vector / Shutterstock