Last year, my first in medical school at Columbia University, I used a bone saw to slice through the top half of a cadaver’s skull, revealing a gray brain lined with purple blood vessels. This was Clinical Gross Anatomy, the first-year course that has fascinated or devastated (or both) every medical student. You never forget the day you open the skull.

Cutting into the brain, unlike the muscles of a forearm or the arteries running down a thigh, feels personal. As a cloud of aerosolized bone dust particles darkened overhead, reinforced by the thickening smell of singed bone, I wondered how much of my donor’s body I was inhaling. How much of that dust would be engulfed by the immune cells in my respiratory system? And how much of the dust would linger in my airways until my grave?

The physical body is messier, but it’s also easier to manipulate. Perception is lost without that physicality.

It was the culmination of months of learning to be comfortable with the body in front of us, a process that accumulated in small pauses between tasks, before digging in with tweezers and a scalpel. How does it feel to hold someone’s lifeless hands for the first time? How do you respectfully flip the body over to crack open the spine? We were required to face these emotions head on, perhaps out of fear that relying solely on textbook diagrams would leave us insulated from the grim realities of human anatomy.

What would happen if Clinical Gross Anatomy became one more casualty of COVID-19? Dissections across the country were reformatted or suspended when lockdowns began in 2020, even as medical educations continued online. Physicians often consider the numerous hours spent in gross anatomy lab to be the most formative of their medical school careers. They transcend the cutting of flesh under the stench of formaldehyde. It’s about learning how to treat someone’s body with respect, work in a team, deal with death. “The anatomy lab is part of the gelling of camaraderie and team-building and peer-to-peer teaching. It’s a rite of passage,” says David Morton, an anatomist at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

The challenge of adapting education to a pandemic is by no means unique to medical education. Educators across a wide range of settings—from preschools1 to boarding schools2 to trade schools3—have struggled to adjust their teaching modalities to this new normal. Researchers have argued that the sudden switch to virtual learning will exacerbate social inequalities, including for children with poor Internet access4 and for women who disproportionately shoulder childcare responsibilities5 as many schools remain closed. In a study published in April in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers analyzing data from the Netherlands found that students made little to no progress during the country’s eight-week lockdown.6

Then there are the more “ordinary” ramifications of this shift away from in-person learning. I mourn the buzz of informal conversations held in liminal spaces, the awkward laughter concluding a light joke offered in a crowded elevator, the accidental bumping into the acquaintance-more-than-friend, the expansion of chatter beyond one’s immediate friend group, the in-between. Although private Zoom messaging—the virtual equivalent of passing notes in class—may allow for some degree of small talk, it occurs at the expense of learning rather than as a supplement to it.

Medical education—particularly Clinical Gross Anatomy—offers a window into what is lost when we lose in-person learning. The pandemic has forced medical schools to re-examine this 259-year-old tradition in the training of American physicians with approaches ranging from limited, socially distanced cadaver-cutting to replacing the entire experience with virtual reality programs. Ultimately, the switch to virtual learning across all areas of education asks us to reflect on the role that physical space and tactility play in our ability to process new information. For medicine in particular, the pandemic has brought debate over the digitalization of anatomical teaching to a head. Streamlining medical education could undermine the knowledge and skills—both scientific and humanistic—physicians are expected to have.

“The last time we had a change of this magnitude was when the Flexner Report came out,” says Jonathan Wisco, an anatomist who teaches at Boston and Northeastern Universities. He’s referring to the landmark 1910 report7 on standardizing medical education that led to sweeping changes in admissions, facilities, and teaching practices, causing one third of American medical schools to be shuttered. The need for physical proximity feels more dire when your education literally depends on touching other beings, both living and dead.

I can vividly conjure my first day, in August 2019, when I gathered, with dozens of my peers, into the crowded anatomy laboratory on the fifth floor of Columbia’s Vagelos Education Center. Groups of four and five huddled around long metal tables that would serve as our workstations for the next five months. On top of each table sat a body, shrouded head to toe in layers of protective sheets. My first patient.

The groups were tasked with “skinning the pectoral region”: cutting out large flaps of skin from the shoulders to below the nipples to reveal the chest muscles underneath. Roving supervisors—in our case, a plastic surgeon—came around from time to time to offer pointers. Hold the scalpel like a pencil instead of a knife; feel free to use your fingers instead of a scalpel to break up the fibrous white connective tissue called fascia between the fatty layer of skin and muscle; avoid the cephalic vein when snipping away at the fat between the shoulder and the chest, so you can examine it later; watch the fibers of the pectoralis major stretch as the arm is extended laterally.

How does it feel to hold someone’s lifeless hands for the first time?

I made the first cut, a vertical line down the center of the chest, and waited for a wave of emotion, or maybe even blood, to overtake me. It never came. In its place was surprise. I was impressed by the sharpness of the blade in my hand, the ease with which I could separate skin with the slightest of pressure. Cutting felt logical, the physical labor a welcome distraction from the grim nature of our task.

The slicing was more tedious than I had anticipated. My thoughts wandered. I found myself struggling to balance an objectification of the body in front of me with an active processing of the very real person it once belonged to. I looked up to see a group of senior students carrying a woman through the lab. She had fainted.

About three-fourths of the way into this first lab session, I surprised myself. While pausing to rest my eyes on the body before me, I had placed my hands on the cadaver’s shoulder. This wasn’t a deliberate act. I wasn’t trying to explore the shoulder with my gloved fingers or feel for the texture of the skin. Somehow my instinctive response to my own appraisal of the body was to offer the gift of human touch, as if I was consoling someone by the bedside. “How odd,” I thought, before returning to my cutting. Normally, if this scenario were played out with a clinician and a living person, the doctor might rest her hands against the arm of a patient to offer human comfort, physical touch augmenting her wishes for a swift recovery or a peaceful passing.

In this case, I was left wondering who was comforting whom.

In November 2020, I observed first-year Columbia medical students learning the anatomy of the head and neck virtually. This material is notorious for being the most confusing section of anatomy. Even for students who spend much of their educational careers contemplating the internal architecture of the human body, the number of holes and strings going through those holes in the skull is shocking. Learning the structures of the head and neck arguably presents the greatest challenge to medical students and faculty working online.

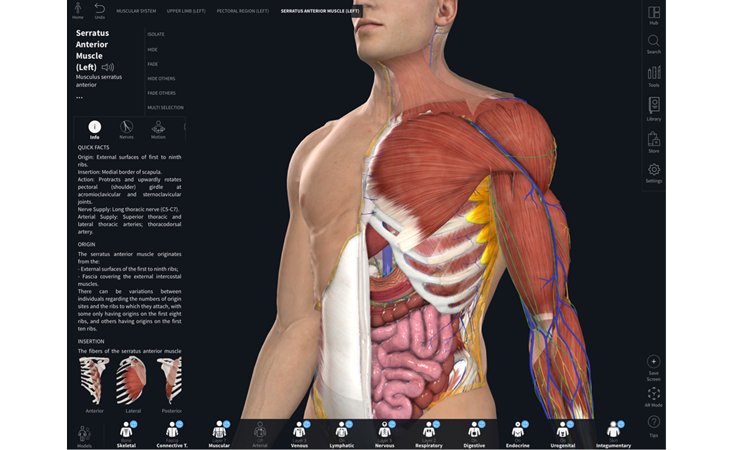

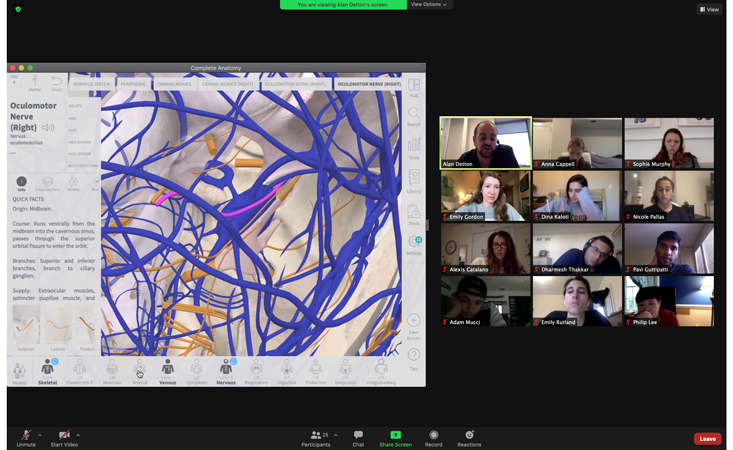

Alan Detton, an anatomy lecturer at Columbia, led a small group session of 24 students over Zoom. He offered playful mnemonics for remembering long lists of structures while guiding students through the complementary systems responsible for the functioning of the human brain on a three-dimensional model in Complete Anatomy, a virtual anatomy software program.

Even with the program’s abilities to highlight structures and hide or reveal layers of various organ systems, finding a cranial nerve amid branches of the internal carotid artery, venous sinuses in the brain’s protective covering, and connective tissue is often like looking at a bowl of spaghetti with the goal of finding a specific strand of pasta.

When I used the program a year before to learn anatomy, it was as a complement to my time in anatomy lab, a virtual guide to the real body before me. The physical body is messier, but it’s also easier to manipulate. Even if many of the nerves and blood vessels in the real body present as eerily similar gray strings, I could dig around, pin things back, explore their depth. Perception is lost without that physicality.

Neha Malhotra is a first-year medical student at the University of Toronto in a unique position to understand the changes this year in gross anatomy. She began her medical school career in the fall of 2019. But because she decided midway through her anatomy course to defer her studies for an extra year to spend time with family, she also experienced “virtual anatomy” in 2020. Learning online, she tells me, is no substitute for the real thing, even though the real thing is exhausting.

“It would be six hours of standing in a lab, a lot of content, dissecting, while also trying to learn and test each other,” Malhotra says. “It didn’t leave a lot of room for absorbing the material. But being in the anatomy lab and embodying that role of a medical student learning anatomy on a deceased body does make you feel like you’re going to be a doctor.”

The pandemic has underscored the value of physical presence, the connections forged by touch.

In particular, Malhotra says, “I remember learning that the pterion is so weak by holding the skull up to the light because the light went through that section, unlike anywhere else.” The pterion is a region on the side of the skull right behind the temple where four bones meet. “I’ll never forget worrying about the vulnerable middle meningeal artery lying underneath and the potential for trauma to cause an epidural hematoma.”

We discuss how some of these experiences took us by surprise. I remember running my fingers inside our donor’s gallbladder to count his dozens of slippery gallstones, my vinyl gloves sliding through black bile. I was somewhat repulsed by the task, yet I couldn’t help but acknowledge that there was an extraordinary intimacy in discovering the contents of another’s organs. And there were moments that we couldn’t quite brace ourselves for. We butterflied the penis, slicing the shaft neatly in half to reveal the spongy tissue within.

I steadied myself through these moments with reminders of my donor’s humanity. I mentally treated the process of tidying up after each lab as “tucking in” my donor as we cleaned the dissection table, sprayed his body with preservatives, and covered his body with protective blankets. We never gave him a name—as many medical students do. We were afraid of giving him the wrong one.

This spring, Columbia medical students have returned to campus. Dissections have resumed, though time in the lab is cut by approximately two-thirds compared to normal years. Nevertheless, many are thankful for the experience. “It would be stressful to have the first time we see a specific body part be on our surgery rotation in the operating room, rather than in the comfort of an anatomy lab,” says Emily Gordon, a first-year medical student at Columbia.

As in most areas of life, the pandemic has underscored the value of physical presence, the connections forged by touch. For medical students, bonds are forged by sharing the same air for hours at a time, toiling over a body lain supine on a table before them. The cadaver serves as a bridge, from present student to future physician.

Today, as I interview patients in the hospital, I am still crafting my own understanding of what it means to be a good doctor. But as someone who spent eight months learning how to console, guide, and treat patients from the safety of a computer screen, I believe my hands are steadier for having held those of a man whose name I will never know.

Michael Denham is a second-year medical student at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

References

1. Yildirim, B. Preschool education in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic: A phenomenological study. Early Childhood Education Journal (2021). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01153-w

2. Kaysen, R. The boarding-school boom. The New York Times (2021).

3. Bosma, A. How do vocational school students get hands-on education during COVID-19? Telegram & Gazette (2020).

4. Stelitano, L., et al. The digital divide and COVID-19. RAND Research Reports (2020). Retrieved from DOI: https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA134-3

5. Bateman, N. & Ross, M. Why has COVID-19 been especially harmful for working women? Brookings.edu (2020).

6. Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M.D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2022376118 (2021).

7. Duffy, T.P. The Flexnor report — 100 years later. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 84, 269-276 (2011).

Lead image: pathdoc / Shutterstock