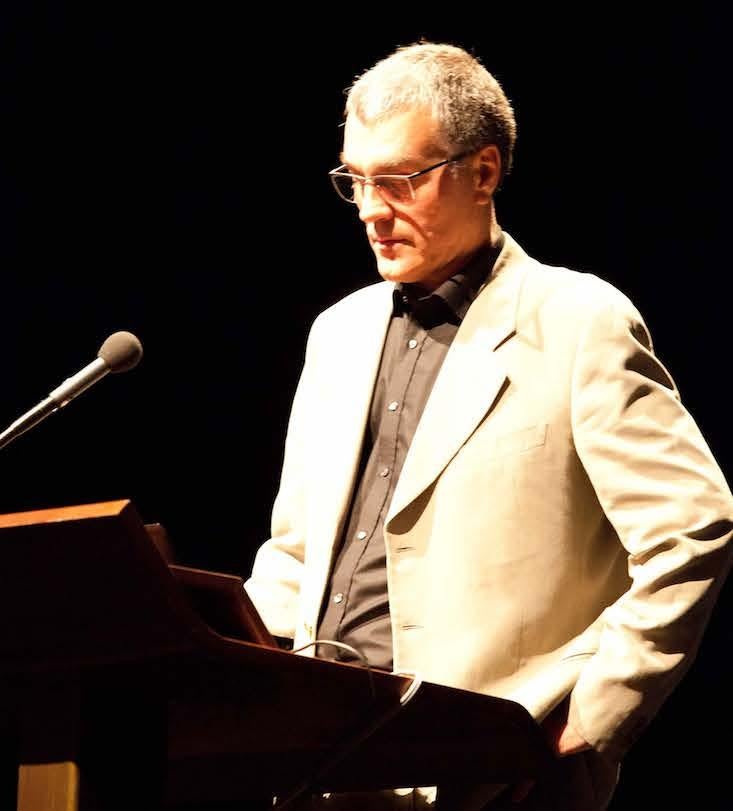

In his 2003 book, Being No One, Thomas Metzinger contends there is no such thing as a “self.” Rather, the self is a kind of transparent information-processing system. “You don’t see it,” he writes. “But you see with it.”

Metzinger has given a good amount of thought to the nature of our subjective experience—and how best to study it. A fellow at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, he directs the Neuroethics Section and the MIND Group, which he founded in 2003 to “cultivate,” he says, “a new type of interdisciplinarity.” To bridge what he calls the academic variant of the generation gap, the group is formed of philosophers and scientists—young and old—interested in psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience.

There’s a long history of conscious self-models on this planet.

When I spoke to Metzinger recently, he explained that the self evolved as a biologically useful construct to “match sensory perceptions onto motor behavior in a meaningful way.” Earlier this year, Metzinger made waves by publishing an article in Frontiers in Robotics and AI that argued that virtual reality technology—the ability to create illusions of embodiment—will “eventually change not only our general image of humanity, but also our understanding of deeply entrenched notions, such as ‘conscious experience,’ ‘selfhood,’ ‘authenticity,’ or ‘realness.’”

In our conversation, we discussed the origins of the self, intimations of mortality, what those who champion a singularity—an immortal union of brain and computer—are missing, and how virtual reality could perhaps push the self into entirely new modes of experience.

What do you mean when you say the self doesn’t exist?

We know there is a robust experience of self-consciousness; I don’t doubt this. The question is how could something like that emerge in evolution in an information-processing system like the human brain? Can we at all conceive of that being possible? Many philosophers would have said no, that’s something irreducibly subjective. In Being No One I tried to show how the sense of self, the robust experience of being someone, could emerge in a natural way in the course of many millions of years of evolution.

The question was how to arrive at a novel theory of self-consciousness, what a first-person perspective is, that, on the one hand, takes the self really seriously as a target phenomenon and, on the other hand, is empirically grounded. If we open skulls and brains we don’t find any entity that could be the self. It seems there are no arguments that there should be a thing like a substance, a self, either in this world or outside of this world.

What explains the evolution of a self?

I think even simple animals that can’t have beliefs or higher cognitive states about themselves have a robust sense of selfhood. There’s a long history of conscious self-models on this planet. They have been here long before human beings have arrived on the scene; they are a product of evolution with many biological functions.

One, for instance, is to control the body—to match sensory perceptions onto motor behavior in a meaningful way. Another much deeper one is the unconscious forms of self-representation; for instance, the immune system that biological organisms have evolved. A million times every day our immune systems says, “this is me” or “this is not me,” “kill or don’t kill,” “cancer cell” or “good tissue.” If it would make a mistake in one of these selections, you would already have one malignant tumor cell every day. So we are grounded in very efficient mechanisms of defending the integrity of the organism, the life-process itself.

What’s most unique about the human self as opposed to similar mechanisms in other organisms?

In humans I think something very special has happened. Our self-models have opened the door from biological evolution into cultural evolution. They made living together in large societies possible, and there are, of course, long stories to be told there, because we can use our own self model to understandwhat another human being believes or desires, something we cannot perceive with our sensory organs. But if we have a self model of ourselves, our own internal model, we can use it to simulate mental states.

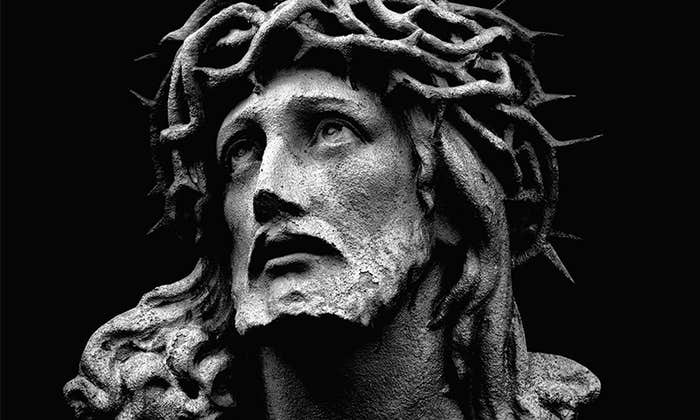

Here we come into a very interesting and deeper principle. There is mortality denial. There is the theory of terror management, which says that many cultural achievements are actually attempts to manage the terror that comes along with insight into your own mortality. The way I have put this is that, as biological beings for millions of years we operate under biological imperatives and almost the highest one is you must not die, under no circumstances.

Now, we human beings, we have a problem that no creature before us had. We have this brand new cognitive self-model and we have this insight that you will die—everybody dies—and that creates an enormous conflict in our self-model. Sometimes I call it a chasm or a rift, a deep existential wound that is given to us by this insight—all my emotional deep structure tells me there is something that must never happen, and my self-model tells me it is going to happen.

How does a self help deal with the knowledge of death?

Animals self-deceive, and they motivate by self-deceiving. They have optimism bias; just like human beings, different cognitive biases emerge. So we have to efficiently self-deceive. The self becomes a platform for cultural forms of symbolic immortality, the different ways human beings tackle the fear of death. The most primitive and simple, down-to-the-ground way is they become religious, a Catholic Christian, for instance, and say, “It is just not true, I believe in something else,” and form a community and socially reinforce self-deception. That gives you comfort; it makes you healthier; it is good at fighting against other groups of disbelievers. But as we see in the long run, it creates horrible military catastrophes, for instance. There are higher levels, like, for instance, trying to write a book that will survive you.

How can virtual reality change the self?

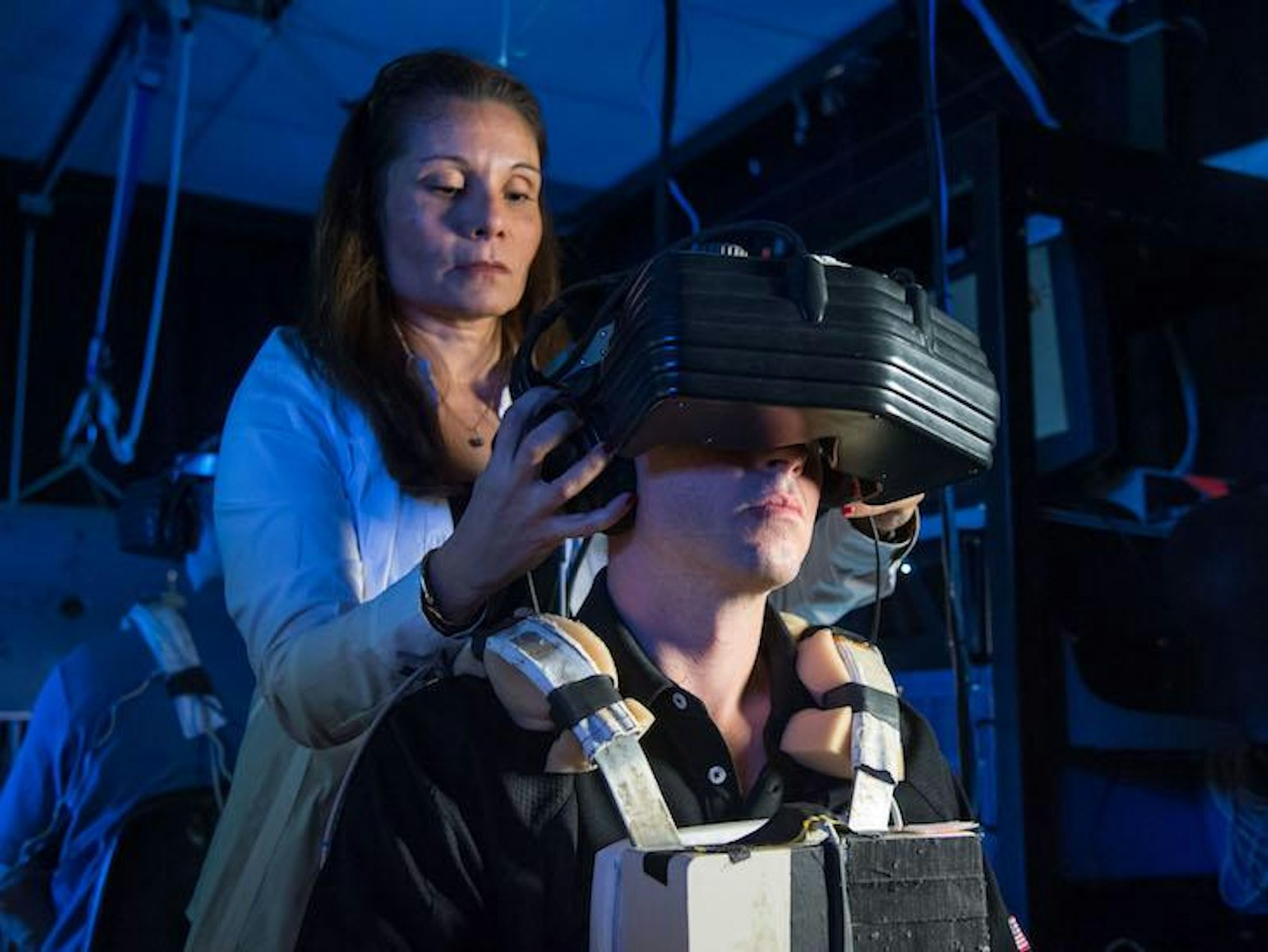

That is a very interesting question. What my colleagues and I have done is remote-control a robot directly via brain computer interface. With your motor imagery, you control a robot 4,000 kilometers away, through the Internet, while looking out of the robot’s eyes with virtual reality goggles while you’re in the brain scanner generating motor imagery. This is, of course, a new form of embodiment. It’s not that your sense of self literally jumps over into an avatar or into the robot, but what you do is you create a complex causal loop by which an external tool—a robot, a second body—is being made directly controllable by you, with your own mind.

Now, of course, this offers itself for mortality denial; there is a religion already in California. It’s all these uploading freaks—the Singularity University, the techies. It promises immortality, but it doesn’t have all the old-fashioned stuff with God. You find these people who say will we upload our self-models into virtual reality in 30 years. They get big investors by saying this.

You don’t buy it? Why couldn’t we upload a self?

The problem—the technical problem—is that a large part of the human self-model is grounded in the body, in gut feelings, in inner organ perceptions, in the vestibular sense, and therefore you cannot really copy the human self-model out of the biological body unless you would at some point really cut it off, so to speak. And then you would maybe have a sense of self jumping into an avatar, but you would not have all that low-level embodiment, the gut feelings, the emotional self-model, the sense of weight and heaviness—all that would be gone.

Maybe we could create very different forms of selfhood and offer them for augmentation, but for a number of reasons I think that the whole idea of actually “jumping” out of the biological brain and into virtual reality completely has probably insurmountable technical problems. It also has a philosophical problem because the deeper question is, of course, what would jump over into the avatars if there is no self? It’s just like discussing reincarnation with Buddhists; what is it that would be reincarnated—your neuroses, your greed, your ugly childhood memories? If there is no substantial self in here right now, what is it that you would copy into an artificial medium?

Nevertheless, I think we’re going to see some dramatic changes in human self-awareness through these new technologies in the coming decades—no doubt about this. We may generate wildly different forms of self-experience.

What’s the biggest challenge of creating those different forms of experiences?

One key word is “embodiment.” The bodies we have now and the way our conscious self-model is grounded in these bodies has been optimized for millions and millions of years, with our biological ancestors, with monkeys swinging through branches. What we have in this biological body is so optimized and so robust because it has incrementally evolved over millions of years by trial and error—literally millions of our ancestors dying for us—to have this fluid and context-sensitive body control right now. This dense form of embodiment in virtual reality may be far away.

But could we one day be embodied in virtual reality?

There is another possibility: We might have another form of embodiment, a technological form. Maybe it is something without gut feelings; maybe it is something without the sense of weight, for instance. Maybe we will have different artificial self-models that we learn to control, and with this process have different forms of self-experience as well. Why should we just replicate what biology has created? Maybe we want to create something more interesting or more cool?

Cody Delistraty is a writer and historian based in Paris. He writes on books, culture, and interesting humans for places like The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and Aeon. Follow him on Twitter @Delistraty.

The lead image is courtesy of NASA Johnson via Flickr.