A few months ago, I sat poolside with friends in Palm Springs. Amid the quiet desert sublime, we reminisced about all the live music we’ve experienced over the years, just about every big and small act since the mid-80s: Prince, David Bowie, Guns ‘n Roses, Bruce Springsteen, and the Yeah Yeahs Yeahs among the them. But My Bloody Valentine, we decided, was the ultimate experience. The group is reportedly among the top-10 loudest bands of all time, louder than Black Sabbath or Metallica, but still quieter than the Who. My Bloody Valentine’s beautiful, shoegaze noise rolls off the stage and over the crowd like invisible boulders.

Pharmakon, whose performance I recently attended, wasn’t anything like this. Pharmakon is a lone woman, Margaret Chardiet, who tortures tones and pulses out of mixers, loops, and other assorted electronics, and she also screeches into the mic. It wasn’t exactly music to me, more a physical experience. At the climax of her performance at Gray Area, a space dedicated to art and technology in San Francisco’s Mission district, she pulled out an A/V cord, taped it up her forearm, slapped her head and slid her arm all over her body, making staccato crashes that sounded like marching band equipment being thrown into a dumpster. Pharmakon vibrated the walls, the floors bounced, and anywhere I stood or sat, I was shaken by the air that was quaking from her amp’s vibrations. I loved it.

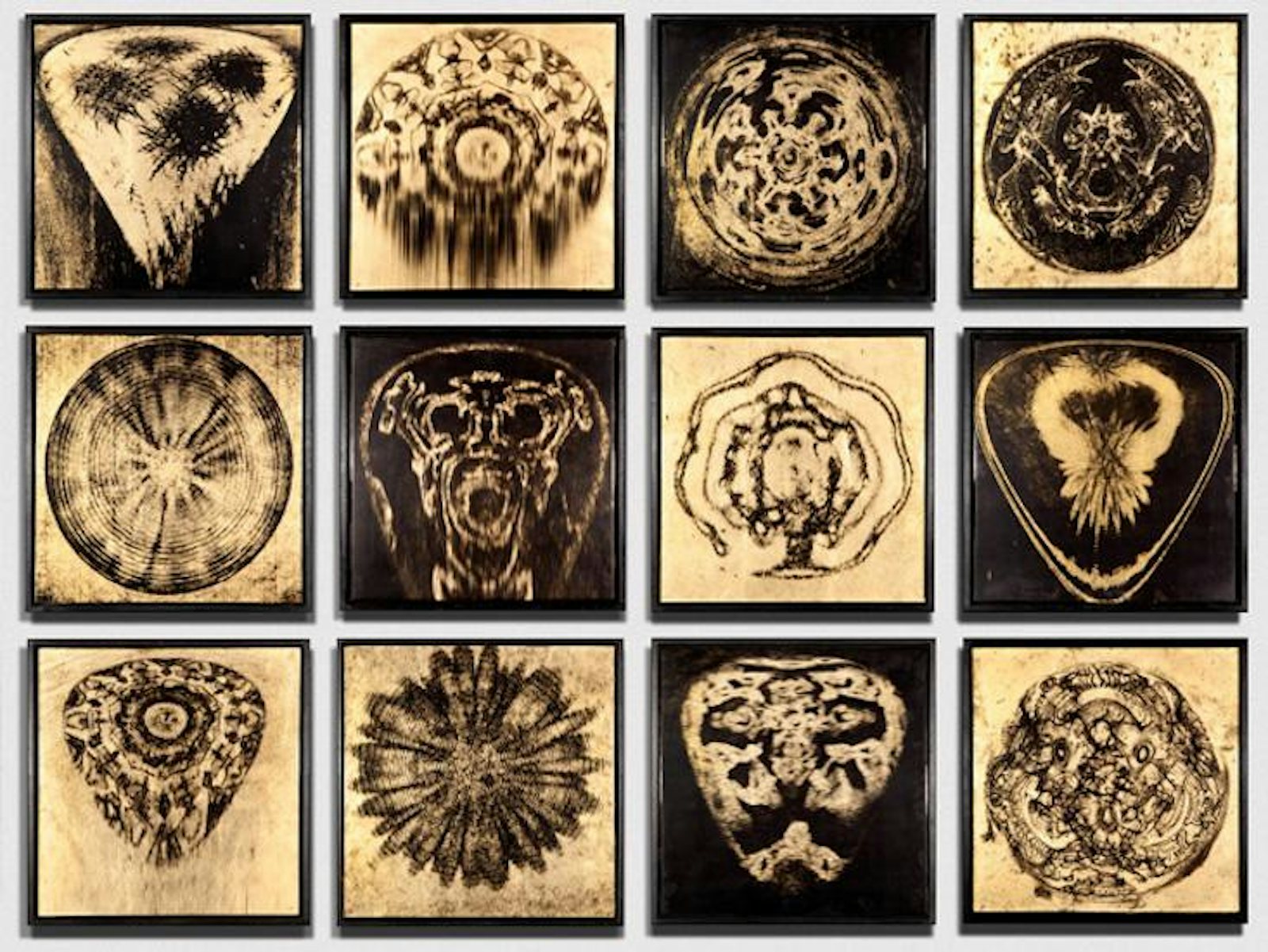

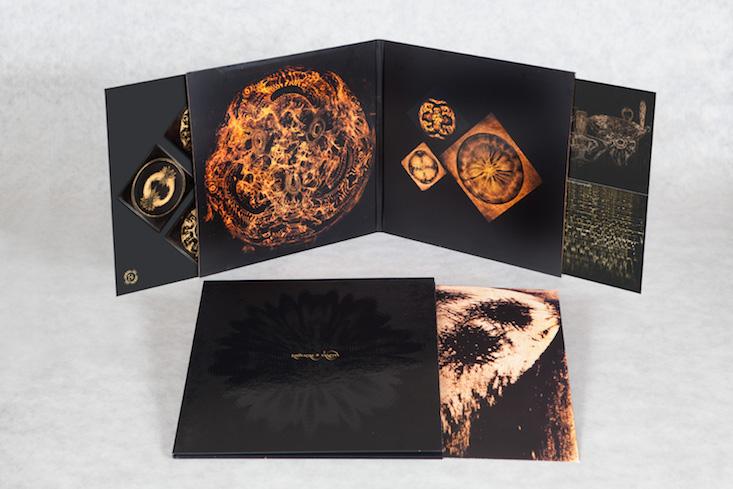

While My Bloody Valentine and Pharmakon may test the limits of music’s loudness and strangeness, other artists experiment with music in ways that are quieter and perhaps more scientific. Resonantia, released last year by artists Jeff Louviere and Vanessa Brown, for example, explores the phenomenon of cymatics—the patterns that sound waves induce in physical objects (Jack White’s “High Ball Stepper” music video is a good example of the phenomenon). Louviere was struck by the idea that each note produces a particular shape in liquid. To investigate these patterns, he rigged up a contraption involving a frequency generator on his laptop, a rebuilt amp with a speaker pointing upward into a plastic vitrine filled with ink-black water, and a guitar tuner.

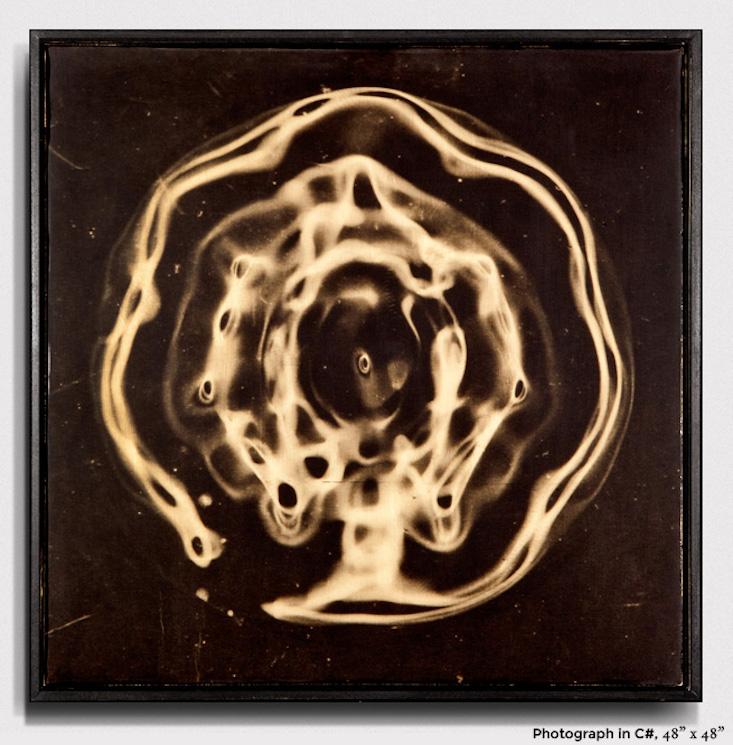

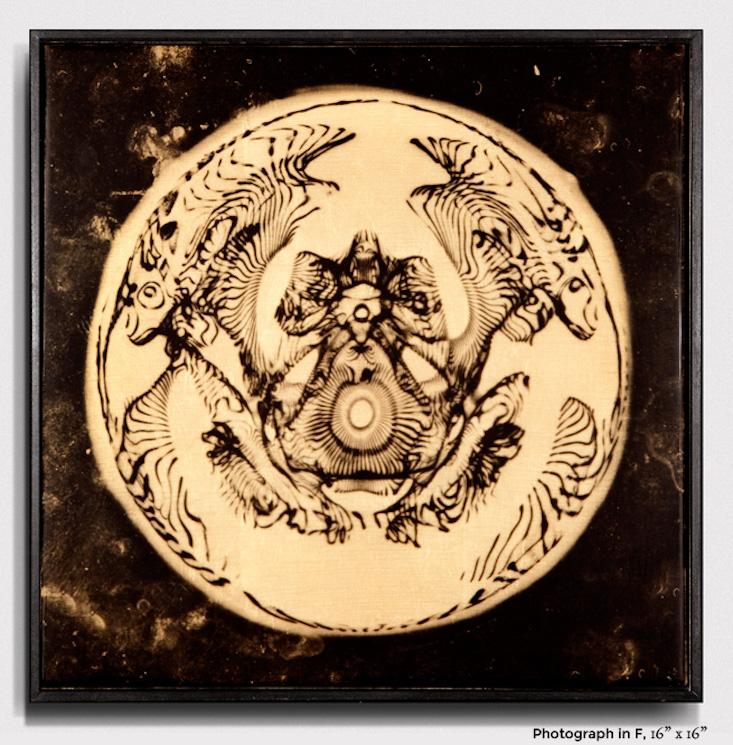

Louviere vibrated the water with the amp by adjusting the generator’s frequency. As he did so, he used his tuner to seek out the frequency of each of the 12 notes—A, B, C through G, plus the five halftones. While Louviere dialed the knobs, Brown stood on a ladder above the contraption illuminating the water with a ring light, her camera in hand. When the tuner registered a note—reading 220 hertz, the frequency that produces an A, for instance—Louviere stopped adjusting. As each note’s unique vibration induced its characteristic pattern into the water, Brown captured it with her camera. The pair worked together to obtain a “portrait” of each of the 12 notes.

In each, Louviere and Brown saw a distinct image: G looks like a devil, C# is the tree in the Garden of Eden, and F is something like the underbelly of a frog. If you were to repeat this experiment, you would get the same designs.

Pressing further their idea that “sight can be seen and images can be heard,” Louviere turned the 12 sound-induced patterns back into sound using Photo Sounder, a program that assigns sounds to the black and white values it scans along the x and y axes of an image. After applying the program to the 12 portraits, Louviere had 12 very distinct, “odd and bleepy” sound files, which he mixed together into a final soundscape born from the visuals of all 12 notes.

Is there any correspondence to the sound of G and its ghoulish portrait? Not likely. However, notes do seem to have personalities and have gained reputations over the centuries. According to Daniel J. Levitin in This is Your Brain on Music, the medieval Catholic Church banned the playing of an “augmented fourth, the distance between C and F-sharp and also known as a tritone,” naming the powerful dissonance Diabolus in musica.* In A History of Key Characteristics in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries, the musicologist Rita Steblin suggests that G major is not ghoulish at all; rather, it sounds like “every calm and satisfied passion, every tender gratitude for true friendship and faithful love.” C major has the air of “innocence, simplicity.” Meanwhile, G minor sounds like “discontent,” and C minor is the “sighing of the love sick soul.”

Now, we can see all of these notes for ourselves.

Heather Sparks is an advertising copywriter, freelance writer, and curator of Science Sparks Art, her blog about the intersection of art and science. She studied molecular genetics at Ohio State University, has a graduate degree in science journalism from New York University, and lives in San Francisco. Follow her on Twitter @SciSparksArt.

*Correction: This sentence erroneously said the note sequence D-E-F was banned.