Adam Magyar’s gone viral. His recent series Stainless, in which video recordings of subway platforms are played out in super-slow-motion, has been rippling across the web. Magyar first films people on the platform from a speedily arriving train and then slows the footage down, highlighting details and expressions that are often missed and rarely remembered. Regardless of station—Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, Tokyo’s Shinjuku, or New York City’s Grand Central—Magyar’s video excerpts show crowded subway platforms that are at times haunting, at others elegant. Waiting for the next train never looked so compelling.

This two-minute excerpt is one small piece of the Grand Central clip; the entire video runs almost 11 minutes, showing a scene that only lasted about a dozen seconds in real time. If you were standing next to Magyar when he shot each scene, rushing into a station at close to 30 miles per hour, you probably wouldn’t have given a second thought to two guys laughing at some shared joke, or a pair of girls running across the platform at Alexanderplatz. There wouldn’t have been enough time. But through Magyar’s lens, these actions have been practically frozen and made meaningful.

Part of the reason Magyar’s project has struck such a chord is the fine details he’s captured, like the crease around the mouth, the wisps of someone’s hair. And he’s focused on the most interesting sets of crowds, like that on the Alexanderplatz (below), where the two girls running in the background—a “gift,” he says—make all the difference between one group of waiters and another. Much of the final product can be attributed to his ample preparation. “I always spend more time with planning than capturing,” he told me recently over email. “You make your calculations and tests…and then the image happens just as you imagined. It’s a pretty amazing feeling.”

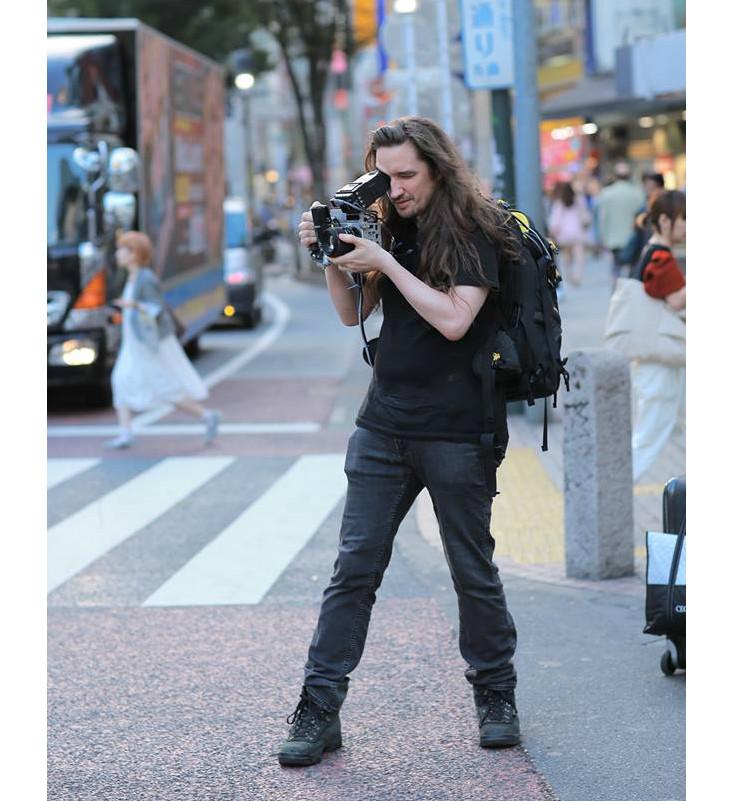

Magyar says that if he finds the right energy in a spot, he doesn’t really have to wait long at a station to capture the right sequence, though he spends nearly all his time in a subway system if he visits a city to shoot it. In the case of Shinjuku, he only ended up shooting two sequences after hanging out at the Tokyo station for a couple of weeks. But the right equipment is just as important as good timing.

Slow-motion video works by using a camera to capture frames of a moving image faster than our eyes can perceive them, and then playing them back much more slowly. Magyar filmed the throng of people at about 1,300 frames per second, 54 times the 24 frames per second used as a standard in movies. Some research shows that our eyes, and brain, can identify an image in as little as 13 milliseconds—a blink of time that would correspond to approximately 75 frames per second, only 1/17th as fast as the footage in Stainless. (Magyar used a modified Optronis camera that can actually shoot up to 100,000 frames per second, which would slow down motion to 1/4000th of its usual speed.)

After capturing the footage, Magyar processed it with software he created over a span of a couple of years. His DIY ethic stretches across all aspects of his work, from the computer programs he uses to correct raw data, to his modified camera, to gadgets he invents, like a beeper-sized sensor that measures light flickering in the often dank netherworld of subway systems.

Magyar isn’t the first to create this type of visual piece. One amateur photographer, Graeme Taylor, captured the scene of a train passing a platform in Bath, England. Trey Ratcliff slowed down urban motion on various streets across Tokyo. “In a technical sense, I’m not doing anything that hasn’t been done yet. Quite a few slow-motion projects have been done in public spaces, too. But as far as I know, no one has scanned subway trains like this, and [with] this quality,” Magyar says.

Although interest in his work spiked quite recently, he’s played with time before, and most interestingly I’d argue, in his still panoramic photographs.

In his Urban Flow series, Magyar creates panoramas of crowded spaces and passing subway trains in Shanghai, Hong Kong, London, and New York. The settings are urban, so both crowds and passing trains are easy to come by. What’s unique in these images is Magyar’s application of a technique called slit-scan , in which, as the name suggests, a camera captures a scene as it moves in front of a thin slit. If the subject is moving at the same rate as the photosensitive film moving past the slit, the subject in motion looks crisp; if they move faster or slower than the film, what you’ll record is a blur.

By the early 20th century, resourceful photographers found that they could make slit-scan pictures by manually or automatically moving film within the camera past the slit. This technology worked—and still works—perfectly for photographing the finish line of a race, where first and second place can be determined by the difference of a nose. You just have to program the mechanical parts inside to move as quickly as the racer will be moving. Magyar’s Optronis camera does the calculations and imaging digitally, scanning a sliver of space only 1 pixel wide—just about the length of a red blood cell.

Magyar says he isn’t satisfied with just being able to utilize a feature of digital technology, like scanning slivers of a scene at high speed or shooting video at super-high frame rates. “Beyond all the tricks, the outcome needs to provide some insight—otherwise, it’ll only be interesting, rather than moving,” he says. So he invests years into preparation for some his series, plotting ways to portray a landscape of urban people, and finally drawing attention to what he has called “the unimportant, the ignored moments.” In a PopTech conference last year, he said, “I was always interested in the rest.” Now we’re interested too.

Yvonne Bang is an assistant editor and video production manager at Nautilus.