By 1967, Vladimir Nabokov had published 15 novels and novellas and six short story collections. But as he told the Paris Review that year, “It is not improbable that had there been no revolution in Russia, I would have devoted myself entirely to lepidopterology”—the study and classification of butterflies—“and never written any novels at all.” As most Nabokov readers know, the great Russian-American writer had a passion for butterflies. He published 18 science papers in the field of lepidoptery, and from 1942 to 1948 was de facto curator of lepidoptery at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

As a lepidopterist, Nabokov’s most audacious claim was that a South American subfamily of blue butterflies was not the result of a single migration, but the effect of five different migrations to South Asia over the course of 10 million years. Few butterfly experts at the time took Nabokov’s papers seriously. At best, they said, Nabokov was an inspired amateur. But in 2011, a group of scientists at Harvard’s School of Comparative Zoology confirmed Nabokov’s theory about the subfamily of blue butterflies, using genetic sequencing.

For years literary scholars have traced the influence of Nabokov’s lepidoptery on his fiction. Nabokov collected, dissected, and illustrated butterflies with the same skill and precision as he created characters and political cultures. On butterfly-hunting trips across America, Nabokov gathered the material for the famous portrait of road-side America that emerges in Lolita. As Mary Ellen Hannibal wrote in this magazine in 2013, “Butterflies were so entwined with the novel that Nabokov celebrated an especially important find—discovering the first known female of Lycaeides sublivens above Telluride, Colo. in the summer of 1951—by making the town the site of the novel’s final scene.”

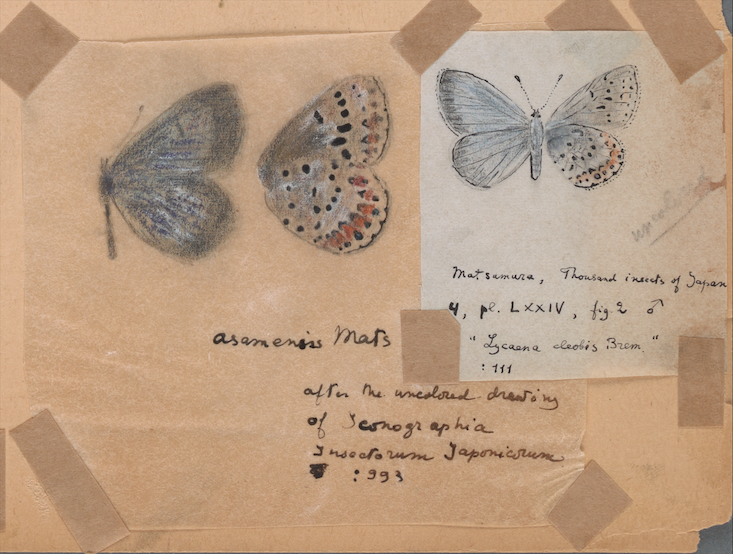

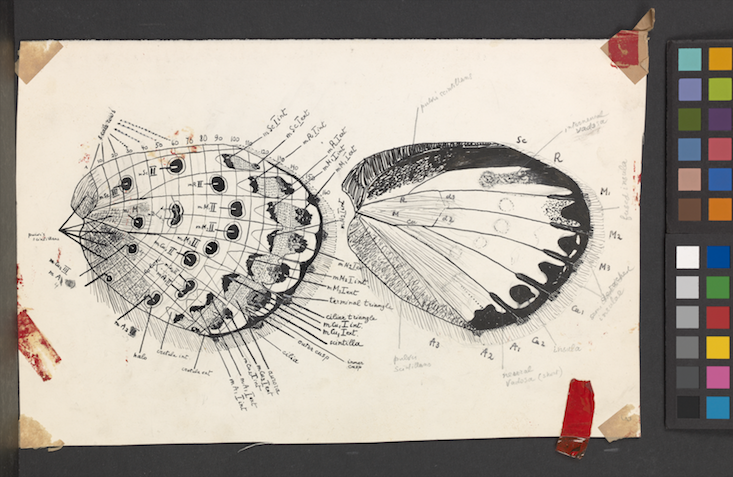

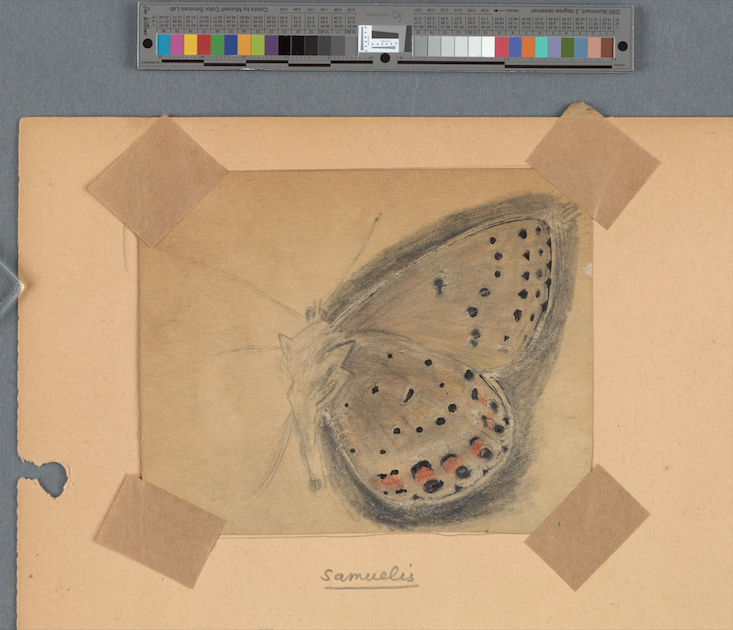

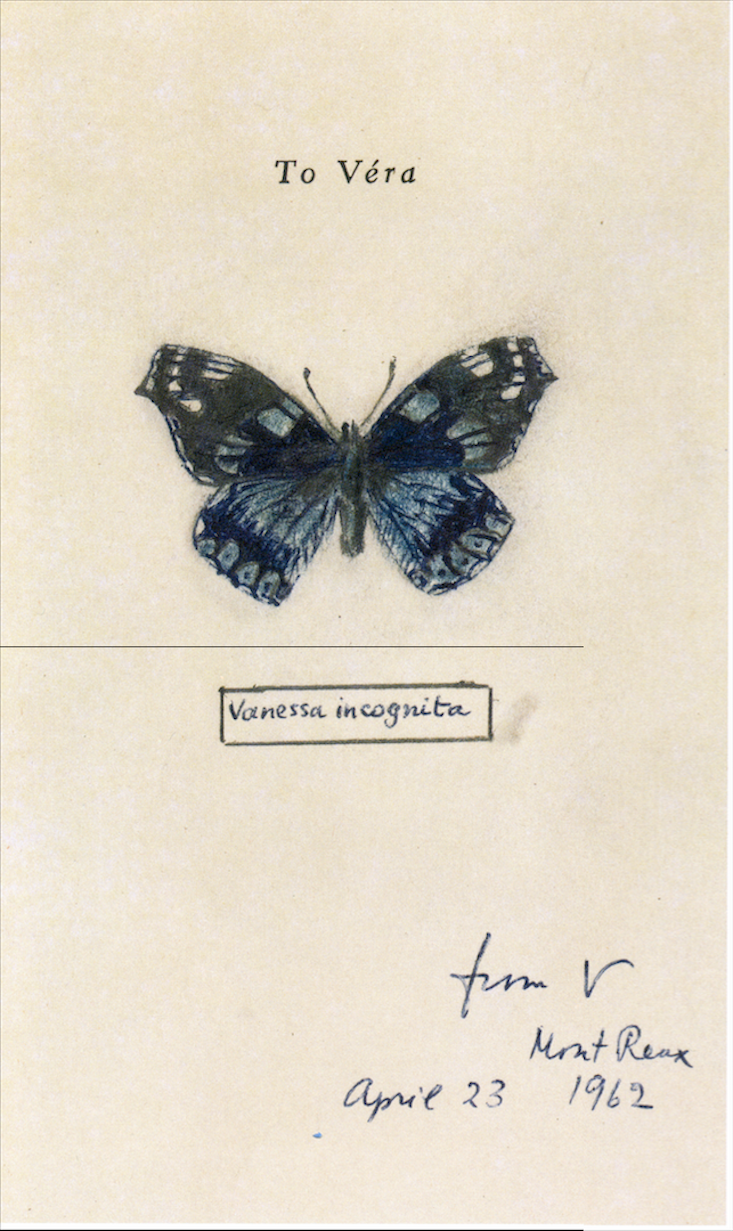

Now scholars have given us a comprehensive portrait of Nabokov’s butterfly passions. Stephen H. Blackwell, a professor of Russian literature and language at the University of Tennessee, and his colleague, Kurt Johnson, coauthor of Nabokov’s Blues: The Scientific Odyssey of a Literary Genius, have just published Fine Lines: Vladimir Nabokov’s Scientific Art. The book features 154 of Nabokov’s butterfly illustrations—most of which have never been seen by more than a handful of Nabokov aficionados—alongside 10 essays written by Nabokov specialists and leading scientists. The book will be of inherent interest to Nabokov fans, but Blackwell believes it will resonate with anyone interested in the pursuit of knowledge and beauty.

Nautilus caught up with Blackwell about the importance of “perceiving with passion,” the connections between science and art, and how the latter imitates life.

Why was Nabokov’s scientific work not taken seriously?

There are two phases of resistance. The first phase was before he was recognized; I don’t think the fact that he was a great writer caused resistance to the ideas he wrote in the 1940s. My colleague, Kurt Johnson, suggests that what happened was Nabokov’s claims and arguments were out of sync with how leading authorities on entomology thought at the time. So they ignored him. It wasn’t until later that Johnston and his colleagues picked up his research and continued what Nabokov had done, and proved its validity. The second—Nabokov didn’t become famous until at least 8 years after his scientific period. Once he was a famous novelist, the bias crept in. People thought that, because he’s an artist, he can’t be a scientist—which we see even today, in one review of Fine Lines.

How did Nabokov’s art influence his science and vice versa?

Nabokov’s interest in the study of butterflies goes back to the age of seven. Then, when he came to the United States and became a lepidopterologist, he was reaching a level of detail in his work that he hadn’t reached before. Before, he was attempting to classify butterflies based on their personal appearance; after, he was looking at the inner machinery of evolution. The work on the inner mechanics of butterfly evolution caused his works to develop a much more complex inner mechanism. If we look at the three novels—Pnin, Lolita, and Pale Fire—after he was doing his dissections, we see that he’s created a nest of inner structures that are much more intricate than in his previous novels, and hidden in the same way that a butterfly’s genitalia are hidden. Butterfly genitalia are the primary means of classifying distinct species, which is why Nabokov spent so much time examining them. So I think he was in some ways trying to mimic nature, and the fine mechanical perfection he found in butterflies, by crafting that very detailed precision into his works.

What’s a great example of scientific precision in his work?

James Ramey, an associate professor of humanities at Universidad Autóa Metropolitana-Cuajimalpa, in Mexico City, wrote an article that found a pattern, a very intricate hidden detailed pattern, that included very specialized counting—clues, hints that you were supposed to count numbers, forwards and backwards, in the text of Pale Fire. It included concealed, strategically hidden typos—a trail of magical breadcrumbs that lead to a fascinating secret solution to one problem in the novel. Not the entire novel itself, a fascinating element in the novel; if nothing else but to give the joy of the search, the ecstasy of discovery, which Ramey teased out in a compelling way. The article demonstrates the mechanical intensity, but also the beauty, of what Nabokov was doing.

What are some other hidden butterfly connections in Nabokov’s novels?

In Pnin, Nabokov features some of the butterfly species he did work on. They play a minor role, but I bet one could draw important parallels between the ecology of these butterflies and the story of the main character of the novel. The species is called the Karner blue, and it’s got a very limited habitat—the butterfly is endangered. In his scientific works, he called it a subspecies, and was unwilling and reluctant to declare it could be named a species in public. But privately he did think it was a species, and he thought it was an interesting creature, and a fragile creature. The main character, Timothy Pnin, he also thinks of in the same way. He has a kind of specialness, an ecological fragility to himself. The point is subtle, but powerful.

What initially inspired you to bring Nabokov’s illustrations to the public?

I did my dissertation on Nabokov’s The Gift, and while I was researching, I noticed some things in the novel that seemed to have a scientific connection. Suddenly I saw the possibility of creating a project about Nabokov where I had expertise, and his interest in science, which I could see in many parts of his book. I spent a few years giving myself a master’s degree worth of reading and study in the history of science, in my own quirky way, to get the context of what Nabokov was learning in his time period—Freudian analysis, psychological theories, and quantum physics were being discussed all over in the 1930s. The more I looked, the more I found. I went through his letters, his drawings—there are over 1,000 of them—looking for anything scientific. I was really overwhelmed. It’s amazing to have all of these drawings that have all this weird beauty to them. I thought, “These needed to see the light of day.”

Susie Neilson is an editorial fellow at Nautilus. Follow her on Twitter @schmeilson.