After a visit from one of his patients in March, 1966, the psychiatrist Maurice Heatly noted, “This massive, muscular youth seemed to be oozing with hostility as he initiated the hour with the statement that something was happening to him and he didn’t seem to be himself.”

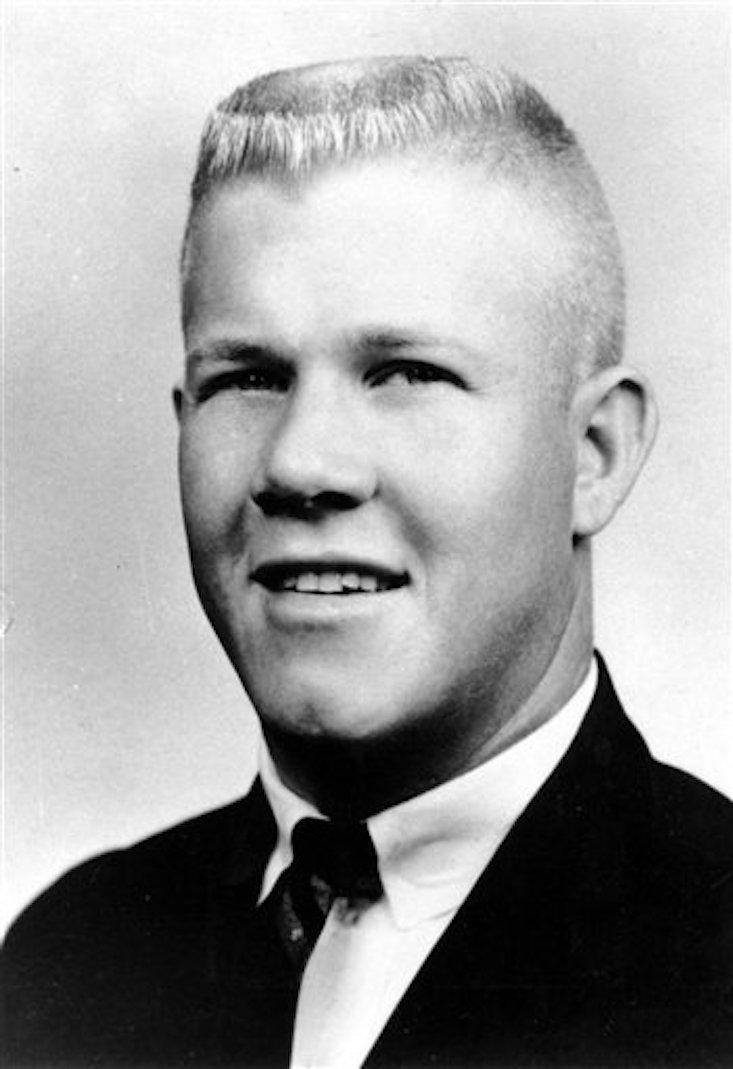

That patient was Charles Whitman, a 25-year-old former Marine who had recently been honorably discharged. He told Heatly, who was on staff at the University of Texas Health Center, in Austin, that he’d been “thinking about going up on the tower [on campus] with a deer rifle and start shooting people.” Several months later, he did just that, killing 14 people, and wounding 31, before being shot dead by the police.

You might suspect this repulsive behavior to be the product of a completely deranged personality, but up until his death Whitman maintained some semblance of rationality, self-reflection, and compassion. For example, it’s both chilling and touching to read his suicide note, which he wrote the night before the shooting and not long after he killed his wife and mother.

“I cannot rationally pinpoint any specific reason for doing this,” he wrote. “I don’t know whether it is selfishness, or if I don’t want her to have to face the embarrassment my actions would surely cause her. At this time, though, the prominent reason in my mind is that I truly do not consider this world worth living in, and am prepared to die, and I do not want to leave her to suffer alone in it. I intend to kill her as painlessly as possible”—“I love her dearly.” (“Similar reasons,” he wrote, “provoked me to take my mother’s life also.”) He also expressed his perplexing wish that some of his money be donated, anonymously, to a mental health organization to help prevent tragedies like the one he would shortly commit.

“A hundred years from now we may be able to talk about brain function in a deterministic way, even if there’s not such a clear obvious organic issue.”

If a patient today complained about the sorts of feelings and thoughts Whitman expressed to his doctors—and he had seen at least five—he would probably have his brain examined. Literally. That is, he would have an MRI to look for abnormalities. Whitman, of course, wasn’t afforded the opportunity, as MRI machines didn’t exist yet. At his autopsy, investigators found a brain tumor the size of a pecan. Some neurologists think it contributed to if not determined his behavior that day, disrupting his emotional processes, perhaps by pressing up against the amygdala, which affects the brain’s fight-or-flight response. You might then wonder whether he was responsible—or should be held responsible—for his actions.

Given medicine can now pinpoint brain abnormalities, how is neuroscience changing our notions of responsibility? It’s a question we recently put to the Columbia University clinical psychiatrist Carl Erik Fisher—who works in the Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry—in our Ingenious interview. He responded that he often taught the example of a mild-mannered man whose behavior in midlife changed dramatically. Notably, he became very interested in sex, at one point making advances toward his daughter. Once a brain tumor was discovered and removed, his behavior returned to normal; once the tumor regrew, the behavior returned.

“When you think in a really rigorous way about psychic determinism and the role of the brain in creating behavior, it’s not clear that example is any different from anybody else,” Fisher says. “If the locus is in their brain, then what makes their responsibility any more or less than someone who has a tumor? A hundred years from now we may be able to talk about brain function in a deterministic way, even if there’s not such a clear obvious organic issue.”

How will the justice system handle this? “The thing that’s interesting to me about the courts is that we are seeing deep philosophical ideas—like free will and responsibility—being put into forced-choice scenarios where you have to say, ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty,’” Fisher says. “We don’t have all the information; there’s no consensus about what the best model for free will or the best theory of punishment is. But, at a certain time and a certain place, someone has to render a judgment. So, how do we do that? What is our mechanism? What is our process for thinking through those sorts of ethical and philosophical issues when we have to, even understanding that we don’t have all the information and there may not be a right answer?”

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @brianga11agher.

Image credit: Phil Roeder / Flickr