How many animal species do you think go extinct every year? Last week I conducted a highly unscientific polling of around 20 of my Facebook and Google Chat contacts, asking that same question. I’m not trying to brag, but I have some really smart friends, many of them with degrees in biology. Typical answers ranged from about 17 to a seemingly ludicrous 400. They were all wrong though—off by orders of magnitude*. In July, a summary article of nearly 80 papers, published in Science, stated that, “Of a conservatively estimated 5 million to 9 million animal species on the planet, we are likely losing ~11,000 to 58,000 species annually.”

If that finding is true, then every year, between .12% and 1.16% of all the animals on Earth vanish. Rodolfo Dirzo, the lead researcher on the Science study from Stanford University, points out that we’ve already lost 40% of the Earth’s invertebrate species in the last 40 to 50 years. Almost half the animals without skeletons have gone extinct within half a human lifetime. The wide range of these estimates reflects our own uncertainty on this subject, but even our low-end assessments are alarming.

Bugs and worms are gross, though; who cares if there are fewer spiders in my house now than in the arachnid-infested ‘60s? Unfortunately the future looks just as bleak for mammals. Dirzo says that if current trends hold, “in 200 years, 50% of the [mammal] species are going to be driven to the very edge of extinction.”

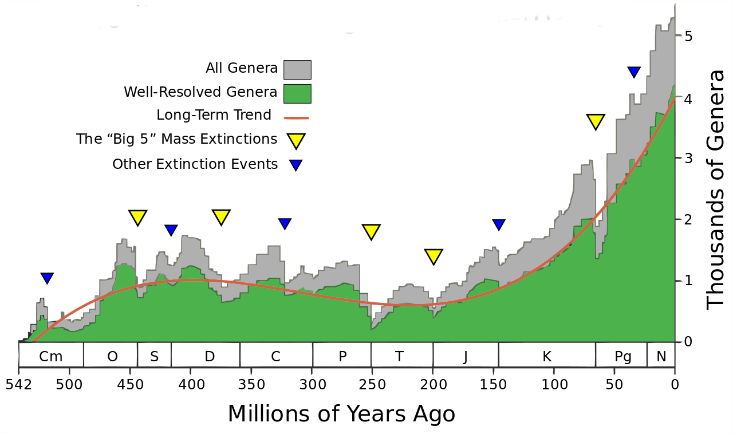

Naturally, all animals go extinct at some point, and it would be reassuring if the rates of extinction had always been this high. By examining the fossil record we can determine just how frequently animals have died out in the past—the “background extinction rate.” The news is bleak: The current rate of animal extinction is around 1,000 times higher than the background rate. That means we are living in the midst of the planet’s 6th mass extinction event. Like the meteoric collapse of the dinosaurs, we are experiencing massive loss of diversity and quantity of life on earth. Some researchers think that as soon as 2050, we may hit a tipping point where various kinds of environmental stress combine to jack the extinction rate jump still higher. So spectacular is this ongoing animal apocalypse that we’ve tentatively declared a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene, a world defined by humans.

If future life forms ever look back at the fossil record from the Anthropocene, one thing should be obvious: Humans are causing the extinction. “There’s no doubt. It’s all human. The rates of extinction without our help, compared to these rates, are vanishingly small,” says Truman Young, a restoration ecologist at UC Davis. Young’s damning assessment is echoed by his colleague Felicia Keesing, a biologist at Bard College. “We’ve certainly had a bigger impact on the face of the planet than any other species except for maybe the first bacteria that helped create the atmosphere,” says Keesing. “[But] those bacteria improved the place, and we haven’t, for the most part.”

In a 15-year-long research project, Young and Keesing set out to investigate the effects of removing animals from ecosystems. They wanted to study what happens when large mammals go extinct, but as Young put it, “If you want to know what happens if you take away pandas, you can’t just go out to the forest and shoot a bunch of pandas.” By fencing off areas of African savanna, the team was able to model an extinction of large mammals. Their local extinction simulation had profound and cascading effects: Small-mammal abundance skyrocketed; fleas (vectors for diseases like bubonic plague) rode in on the thriving mouse populations; venomous-snake abundance rose due to the increased food supply; acacia trees were gobbled up before they could reach maturity. In response to the removal of a single class of animal, an entire ecosystem shifted dramatically.

Does such a profound change reflect the savanna’s frailty or resilience though? Extinctions leave significant voids in our ecosystems—holes in the food chains’ circuitry that conducts calories to any animal fit enough to tap into it. Energy builds up around the gaps and entices new species to fill vacant niches. Young quotes the old adage, “Nature abhors a vacuum.”

In many ways this isn’t surprising. It’s easy to understand the interdependency of ecosystems and food webs; we know that perturbations will have rippling effects. What’s much harder for us to predict, according to Keesing, is what the effects will be. “These were huge animals at high abundance. Of course things were going to change when they were removed,” said Keesing about her savanna study. “It just turns out we’re really bad at predicting what was going to change.” Researchers suspect that removing huge numbers of smaller species will also bring big, unpredictable changes to ecosystems around the world.

The most alarming part of the mass extinction is how it might affect us. We are, after all, animals ourselves; we could be facing extinction too. We are part of the web we’re poking holes into.

But it’s difficult to figure out exactly what the mass extinction will mean for us; we simply do not understand these systems well enough to accurately forecast their futures. Without that understanding, we’re basically swinging a sledgehammer, blindfolded, in a basement, hoping that we don’t accidentally hit a loadbearing wall and bring the whole thing down on top of our heads.

We are, after all, animals ourselves; we could be facing extinction too. We are part of the web we’re poking holes into.

One solution is to remove the blindfold—to try and understand how well these ecosystems work down to the finest details. But really, wouldn’t it just be simpler to stop swinging the hammer? We know the major ways we’re causing the sixth mass extinction event: Dirzo cites the top four as “habitat destruction, then over-exploitation, then the impact of exotic [invasive] species, and then last but not least, climatic disruption.” We know how to not cut down trees; we know how to not hunt animals to extinction; we know how to reduce our carbon emissions. The question isn’t one of possibility, but of desire and ethically arduous sacrifice.

What if one of the required sacrifices is quality of human life, though? Is anyone willing to say that to save our planet and ourselves, we should stop cutting down trees to build houses for people who need them? What politician could ever win on that platform? Yet the fact remains that Earth has a very real carrying capacity that we may have already exceeded. According to Global Footprint Network, in 2014, we will consume about 1.5 times more resources than our planet can offer in the long run. To wrest ourselves from our ecological deficit will require global cooperation, bold leadership, and probably some material sacrifices.

Until the extinction event begins to impact us directly, it’s going to be easy to ignore. The cost of waiting is tremendous, though. “At the very least, we know we’re losing species at a very high rate for a very long time into the future,” says Keesing. We will either begin to make sacrifices and cooperate soon, or the damage we cause to our planet will catch up with us and cause a real humanitarian disaster, in addition to the ecological one.

* Two people—both conservation journalists—guessed in the thousands. Shout out to National Audubon Society and The Wildlife Society for hiring knowledgeable writers.

David Shultz is a Nautilus editorial intern.