In 2002, a group of adults aged 50 and over answered a series of questions about their physical and mental health. A subset of the questions went as follows.

How often do you feel …

1) A lack of companionship

2) Left out

3) Isolated from others

The adults rated their answers on a scale of 0-3 with “hardly ever or never” to “often.” Three points or more qualified that person as “lonely.” Six years passed. In 2008, the researchers followed up with the participants. They discovered lonely individuals were at greater risk to be depressed and less mobile than their non-lonely counterparts. They were also more likely to be dead.

The physiological ravages of loneliness are no mystery to those sunk in “a perfect solitude,” which is, “perhaps, the greatest punishment we can suffer,” wrote philosopher David Hume. The stress hormone cortisol, we now know, suffuses our bloodstream, taxing our hearts and brains, our appetites and sleep.

In her 2016 book, The Lonely City, British writer Olivia Laing explores the pain of her own loneliness in New York City. “What does it feel like to be lonely?” she asks. “It feels like being hungry: like being hungry when everyone around you is readying for a feast.” Laing observes it has “been said emphatically that loneliness serves no purpose.” She quotes sociologist Robert S. Weiss, author of a seminal 1970s study: Loneliness “is a chronic disease without redeeming features.”

In recent years, scientists have sharpened their focus on loneliness, concluding it does have a purpose, does have redeeming features. They are not talking like Thoreau about the benefits of solitude on our creative minds and spirits. They are talking like Darwin about loneliness driving change, an evolutionary correction.

“Loneliness is a warning system,” says Louise Hawkley, a psychologist at the University of Chicago. It is our body telling us we’re breaking from the social bonds that nourished us as a species. “We’re failing to satisfy our fundamental drive to connect with other humans,” Hawkley says. Feeling isolated switches our bodies into self-preservation mode. “What happens with people who are lonely for a long time is their threat-defense programs get activated,” says Steve Cole, a professor of medicine and psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The body interprets loneliness as threatening.”

“Loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.”

In one study from 2009, researchers used fMRIs to test whether lonely brains were more sensitive to threats. Twenty-three participants were placed in an MRI and shown a series of pictures, some of them pleasant, such as money and a rocket lifting off, and others unpleasant, including human conflict. They found that lonely brains respond less positively to pleasant images than non-lonely brains, and more strongly to images of violence and unpleasant social situations. Loneliness spurs the brain into a hyper-vigilant state, unable to relax. The lonely brain doesn’t passively take the world in, but actively interprets it as an unfriendly place.

Hawkley found that lonely individuals take longer to fall asleep, wake up more during the night, and sleep less deeply. “The lonely person’s feeling of not being safe, socially safe, could contribute to disrupted sleep,” she says.

Normally, cortisol is released periodically throughout the day, regulating our metabolism and blood sugar levels, but it’s also released when we feel threatened. Studies show that lonely people have higher levels of cortisol in their systems than the non-lonely, and that even a brief feeling of loneliness triggers cortisol to circulate.

Higher cortisol levels may be responsible for the other physical changes. Some research suggests that there is a link between the system that regulates cortisol and the cardiovascular system. Hawkley has found a correlation between our cardiovascular health and loneliness. In one study, she and colleagues found that lonely, middle-aged adults are more likely to have high blood pressure.

Lonely people also have an increase in inflammatory response, which is also linked to high cortisol levels. Cortisol often reduces inflammation. However, animal studies show that high cortisol can make the cortisol receptors less sensitive, increasing inflammation. Cole explains that when under threat, the body inhibits its viral response, and instead puts its energy into preparing for a bacterial infection from wounds. But if the social threats continue, and the body keeps repressing it’s antiviral response, then the body is less able to defend itself from disease.

At any given moment, 20 to 40 percent of adults in Western countries feel lonely, and experience these physical changes in their bodies whether they are aware of it or not. “It’s not necessarily a bad thing unless it occurs chronically,” says Leah Doane, a psychologist at Arizona State University. But up to 30 percent of lonely sufferers can’t seem to kick it, and it’s the chronic loneliness that harms us. In a meta-analysis from 2010, researchers found that lonely individuals are 26 percent more likely to have an early death, twice the rate of obese individuals.

It’s this unwanted and damaging state that, paradoxically, can reward us. Loneliness “is to our evolutionary advantage,” says Doane. “If individuals perceive loneliness as a stressor, their body may be adapting by helping this individual get up and go.” A study of 7,665 Dutch twins found that traits typically associated with loneliness are about 50 percent heritable, suggesting loneliness is favored by evolution.

In 2012, Naomi Eisenberger, a social psychologist at UCLA, showed that “social” pain co-opts the same neural circuitry as physical pain. An “unwanted romantic relationship breakup,” she writes, activates the same brain region as “heat stimulation.” A broken heart, apparently, is nature’s way of telling us not to get burned.

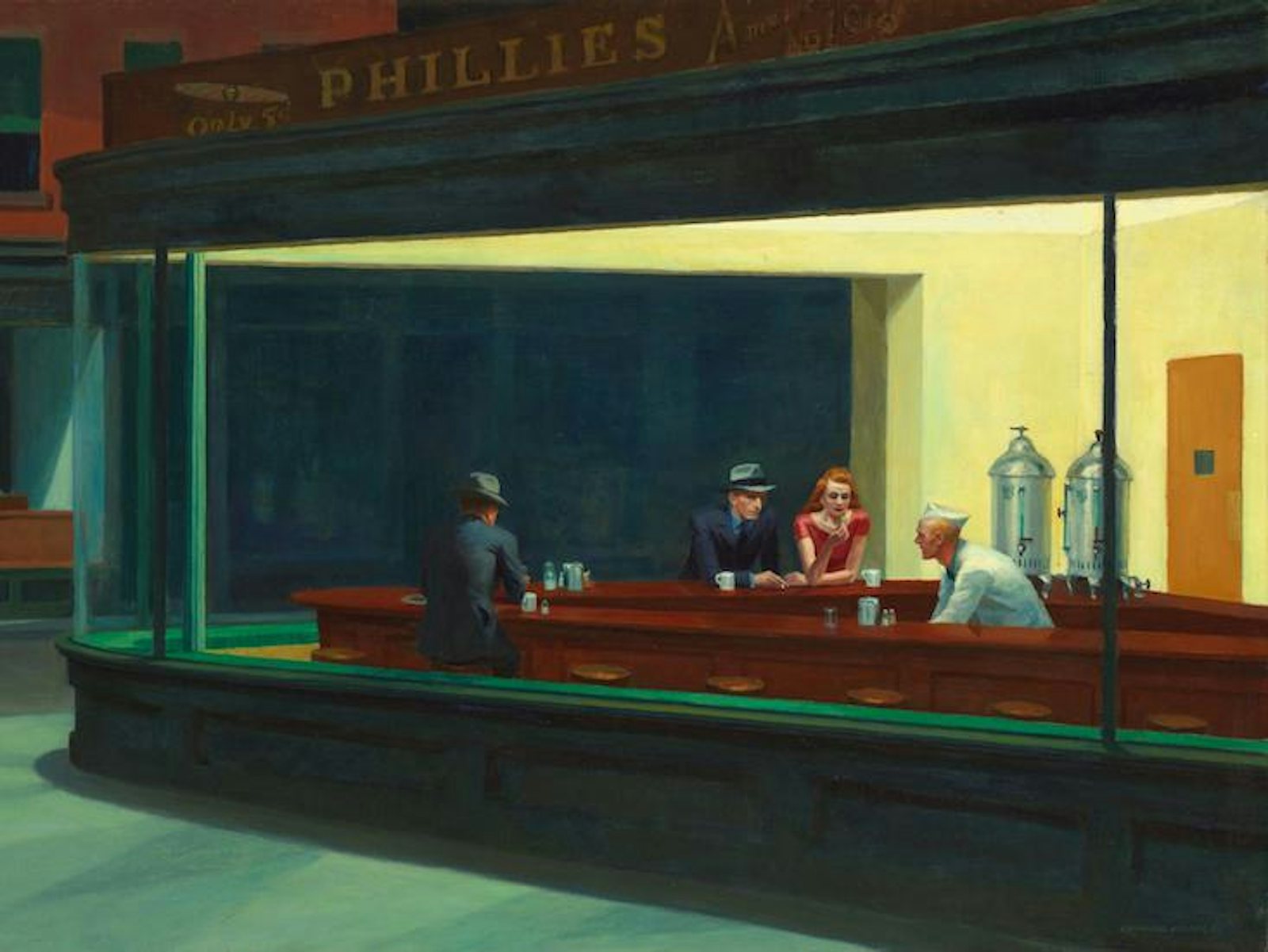

If loneliness is a spur to action, there is a chance for success. After finding solidarity in the lonely tableaus of artists like Edward Hopper, Laing began to feel whole again. What her contact with the artists, and experiences in New York, taught her, she says, is “loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.” “What matters is staying open, staying alert,” she writes.

It’s a message shared by psychologists. “The degree of social connection that can improve our health and our happiness is both as simple and as difficult as being open and available to others,” writes John Cacioppo, a psychologist at the University of Chicago, in Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. Learning to open up, rejoin the group, is ultimately what quiets the ancient warning system.

Regan Penaluna is an assistant editor at Nautilus. Follow her on Twitter @ReganJPenaluna.

Farah Mohammed is a journalist who has written for The Guardian and the Huffington Post. She currently works at Vice Media.