It sounds like science fiction: A citizenry genetically engineered to be democratic. It’s not implausible. Last month, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report touting the promise of a biological engineering technique called gene drive—particularly for dealing with public health problems such as the Zika virus, malaria, and dengue fever. Last year, Anthony James, a biologist at the University of California, Irvine, led a team that used the gene drive to genetically fashion mosquitos with an immune system that inhibits the spread of the malaria-causing parasite. “Quite a few people,” he told STAT, “are trying to develop a gene drive for population-suppression of Aedes”—Aedes aegypti, the mosquito carrying the Zika virus. But officials at the National Academy Sciences say it’s best to be cautious with a technique likely too immature for field use.

It seems like only a matter of time, though, before gene drive becomes a mature technique. After all, it’s just a way to encourage—or block—the inheritance of select genes in a given population. Once it has, what’s to stop gene drive from being used for all sorts of other applications, including ones that enhance the fitness of organisms rather than weakening them? The underlying technology for it, CRISPR Cas9—a gene-editing tool adapted from the prokaryote immune system—can precisely, easily, and cheaply snip strands of DNA, allowing for customizable genomes. With such an accessible technology, it seems likely humans will start to not just take away bad things—like illnesses transmitted by mosquitos—but also add good things.

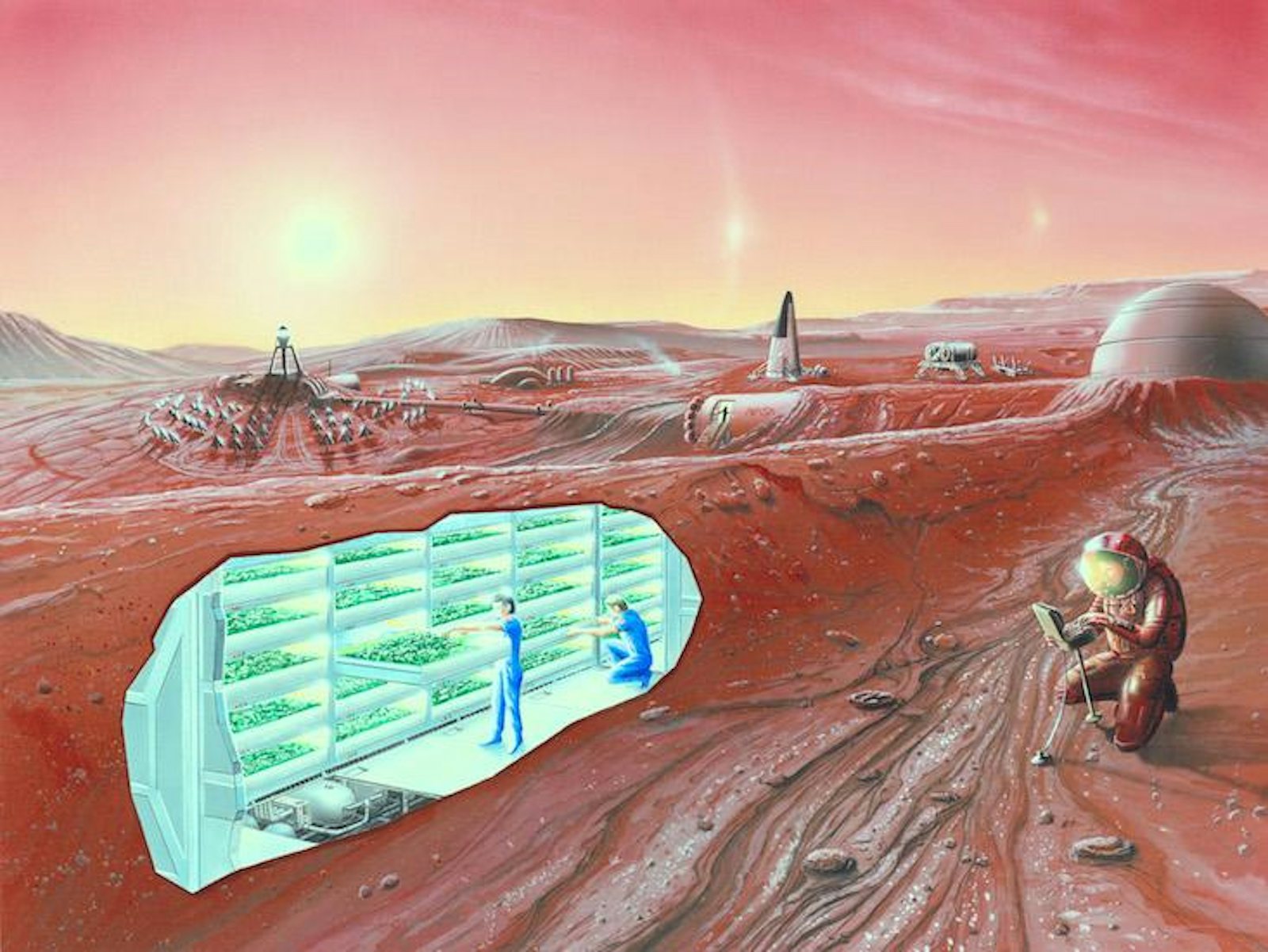

Consider the ideal Mars colonist. Elon Musk’s SpaceX was founded to colonize the Red Planet, and he recently said that colonists on Mars should engage in direct democracy because “the potential for corruption is substantially diminished in a direct, versus a representative, democracy.” Makes sense. Now all Mars needs are women and men who are up for the task. Turns out, political engagement might be in the genes.

“The heritability of political participation and political efficacy is remarkably similar across cultures.”

Research shows that traits associated with political engagement are heritable. Take a 2012 study by Danish geneticists and political scientists. “Given the body of evidence showing that most pro-social traits are genetically influenced it seems reasonable that people’s sense of civic duty and political efficacy are also partially heritable,” they wrote. “Utilizing two new twin studies on political traits, one in Denmark and one in the United States, we show that the heritability of political participation and political efficacy is remarkably similar across cultures.” And in a 2015 study, researchers concluded, “We show that most of the correlation between civic engagement and both positive emotionality and verbal IQ can be attributed to genes that affect both traits.”

Of course, it only makes sense to select civic-minded people to be colonists in the first place. But it stands to reason that a human colony on Mars made of democracy lovers would still benefit from gene drives reinforcing qualities associated with civic participation, ensuring that the colonists would be politically engaged enough for a direct democracy to flourish.

The most practical way would be to isolate the appropriate genes in an existing population of Martian colonists by determining which are crucial to positive social traits. Because political participation and civic duty are subtle targets, comprising potentially hundreds or thousands of genes, scientists would probably have to select some reasonable fraction of the ones most likely to bring about a civic disposition. There’s evidence that highly engaged citizens possess some similar underlying genetic factors, but we don’t know exactly which genes are associated with positive behaviors, nor do we know whether those genes are more responsible for the target behavior than environmental factors. But with genetic technologies constantly improving, scientists may be able to get a better idea of which genes to target by the time a robust colony on Mars exists (Musk says he plans on having the first settlers arrive in 2025).

Once scientists have identified the appropriate genes, they could use CRISPR to implement gene drives in the colonial population so that, as the colonists reproduce, the genetic markers for democratic participation could saturate subsequent generations. This might happen by editing the genomes of human embryos before they’re set to develop, inserting the genes responsible for civic-mindedness. This practice is ethically controversial today, of course, but once its risks of harm are sufficiently reduced, caution surrounding its use will likely follow. Even with these technological and ethical issues, direct democracy in Martian colonies needn’t be a pipe dream.

Josiah Ober, professor of classics and political science at Stanford University, has spent much of his life studying ancient Athens, the Greek city-state renowned for its direct democracy. Direct democracy wasn’t an exclusively Athenian innovation, he says—anthropologists studying hunter-gather groups have shown, he believes, that direct democracy “was the fundamental condition of humans for tens of thousands of years.”

Humans are, in other words, naturally democratic, he says. But as societies get larger, the cost and difficulty of sharing information among people increase, and more complex social hierarchies arise. Direct democracy becomes more of a challenge. Ancient Athens was an exception to the rule, because they “figured out how to scale up our basic human capacity for how we got going in the first place,” Ober says. We may be able to solve the problem of direct democracy at bigger scales, he says, by using gene drive to flood the Martian colony’s population with pro-democracy traits. “It allows us to leverage our basic human genetic advantage.”

But George Church, a geneticist at Harvard University, suggests that gene drives may not, in fact, be very useful for humans. “Gene drives are intended for wild organisms with rapid sexual cycles—ideally measured in weeks—like mosquitoes, rodents, and weeds,” Church says. Because human generations are much longer than mosquitoes’, it takes much longer for genetic changes to show up and take hold in human populations. Church offers a less technologically ambitious, if still challenging, solution: “A more politically engaged population is probably more feasible via social, educational, and political means.”

Ober’s on board with that. Clearly, as Church says, “social, educational, and political means” of various kinds will play a crucial role in sustaining a direct democracy on Mars, should it actually come about. But couldn’t it be the case that a process of propagating traits favorable to democracy, with gene drive, would be helpful, too, however long it takes? Why not do both? As a matter of fact, we know of a colonized planet right now that could use, in plenty of places, direct democracy to diminish corruption.

Peter Hess is an editorial intern at Nautilus. Follow him on Twitter @PeterNHess.