A lot of modern science challenges us to change our behaviors. Results related to climate change, for example, suggest we travel, shop, and eat differently. Psychology and sociology ask us to shift our perceptions of each other.

Once the science is done, though, the work is not over. The next step involves facing one of a scientist’s “most significant challenges,” according to a recent study in PLoS ONE. And that is the headache of dealing with how their message comes across to an ideologically polarized public.

What if scientists were more transparent about their values? Would their results and recommendations be better received and more trusted if they acknowledged any relevant personal beliefs that may have shaped their research? That’s what Kevin C. Elliott and colleagues, authors of the PLoS ONE study, sought to determine with some online experiments. They recruited 494 U.S.-participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk (a “convenience sample”—more “male, younger, more highly educated, and more liberal” than a representative sample) to take a survey; it was advertised vaguely as “Your Attitudes about Important Social Issues in the US” to solicit a broad cross-section of people not particularly interested in, or opinionated about, the issues discussed in the experiments.

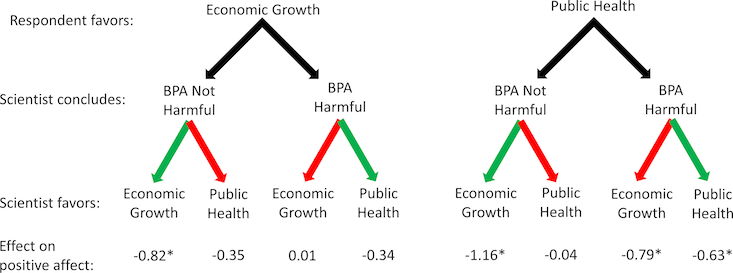

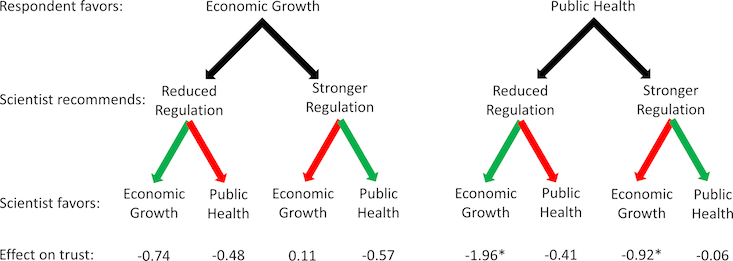

In the first one, subjects read a vignette of a scientist giving a public talk in Washington, D.C. on the health risks of Bisphenol A (BPA), an endocrine-disrupting compound used in plastic consumer products. There’s an ongoing controversy about its effects. The researchers manipulated the vignette to have the scientist’s conclusion (BPA harmful or not harmful) comport with her explicitly stated values (a policy preference for either “protecting public health” or “promoting economic growth”) on the one hand, and diverge on the other; they also accounted for whether the subjects’ values aligned with the scientist’s in each case. In the second experiment, the vignette is manipulated in the same way but features a policy recommendation from the scientist rather than a statement summarizing the weight of the scientific evidence.

In each experiment, participants registered their impressions of the scientist and their conclusions—were they competent, credible, expert, honest, intelligent, sincere, or trustworthy?—on a 7-point scale. Elliott and his team concluded that disclosing a scientist’s values doesn’t boost his or her credibility or the trustworthiness of the conclusion reached. In fact, the additional transparency can reduce them!

The effect also depends, the researchers conclude, “on whether scientists and citizens share values, whether the scientists draw conclusions that run contrary to their values, and whether scientists make policy recommendations.” A broad recommendation to a disparate set of communities holding a spectrum of values will produce a spectrum of responses—without, the research suggests, an overall boost in credibility.

Perhaps scientists don’t need it. Last year, a Pew Research Center report found that Americans trust scientists, alongside the military, much more than religious and business leaders, the news media, and elected officials. Yet the trust Americans place in scientists might mean they should be more transparent and vocal about their findings and policy preferences than they already are: The same Pew report found that, on the topic of climate change, 39 percent of Americans trust scientists “a lot” to give “full and accurate information”—way more than energy industry leaders (7 percent), the news media (7 percent), or elected officials (4 percent).

What do you think? Should scientists take this as a cue to be more open about their values and policy preferences in their research, given this discrepancy in trust in their favor? Or should they continue to keep their values to themselves?

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @brianga11agher.

WATCH: What is missing from the public perception of science.