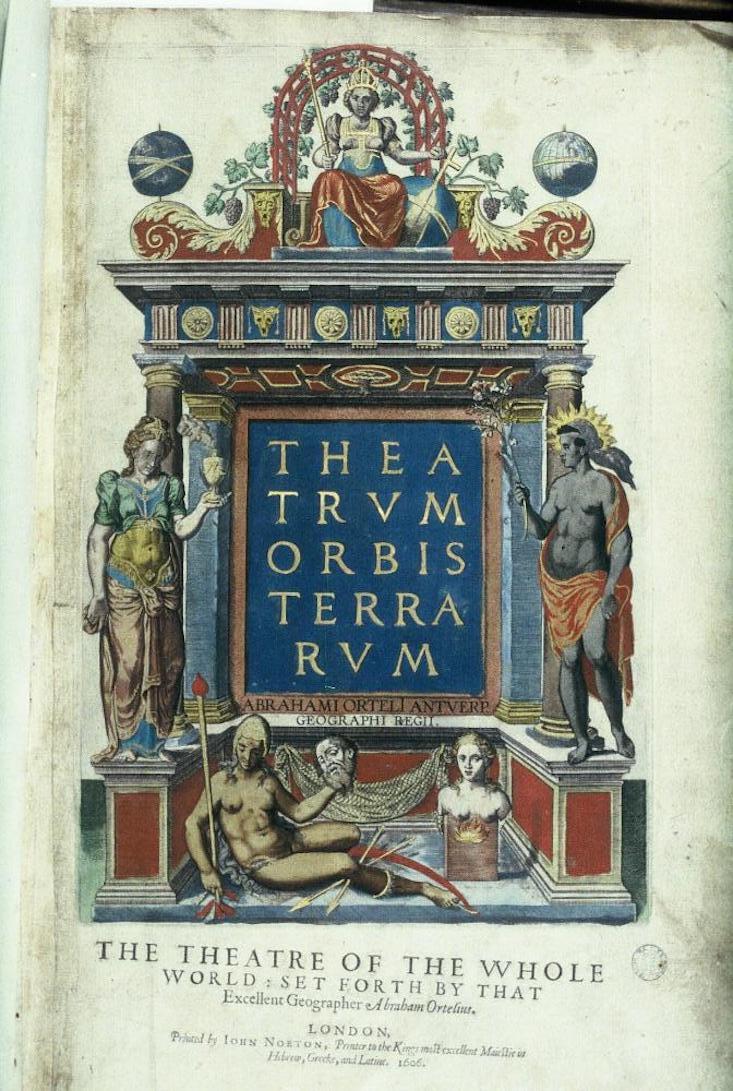

Now that we’re corralled into our homes and apartments, something seems pre-modern in how our worlds have shrunk. Unlike past quarantines, we’re also connected by digital technology to the rest of the globe, calling to mind poet John Donne’s line from a 1633 poem about making “one little room an everywhere.” Donne came of age able to envision a mental map of the globe based on new and detailed evidence about a dizzying array of locations. His poetry is replete with globes, maps, and atlases. What’s considered to be the first atlas was first available in an Antwerp printshop 450 years ago, on May 20, only two years before Donne was born. It was large, handsome, and expensive, with the grandiose title of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, or in English Theater of the Orb of the World. Donne was undoubtedly familiar with it. Produced by the cartographer Abraham Ortelius, it was one of the most popular books of the era. Ortelius had invented the world.

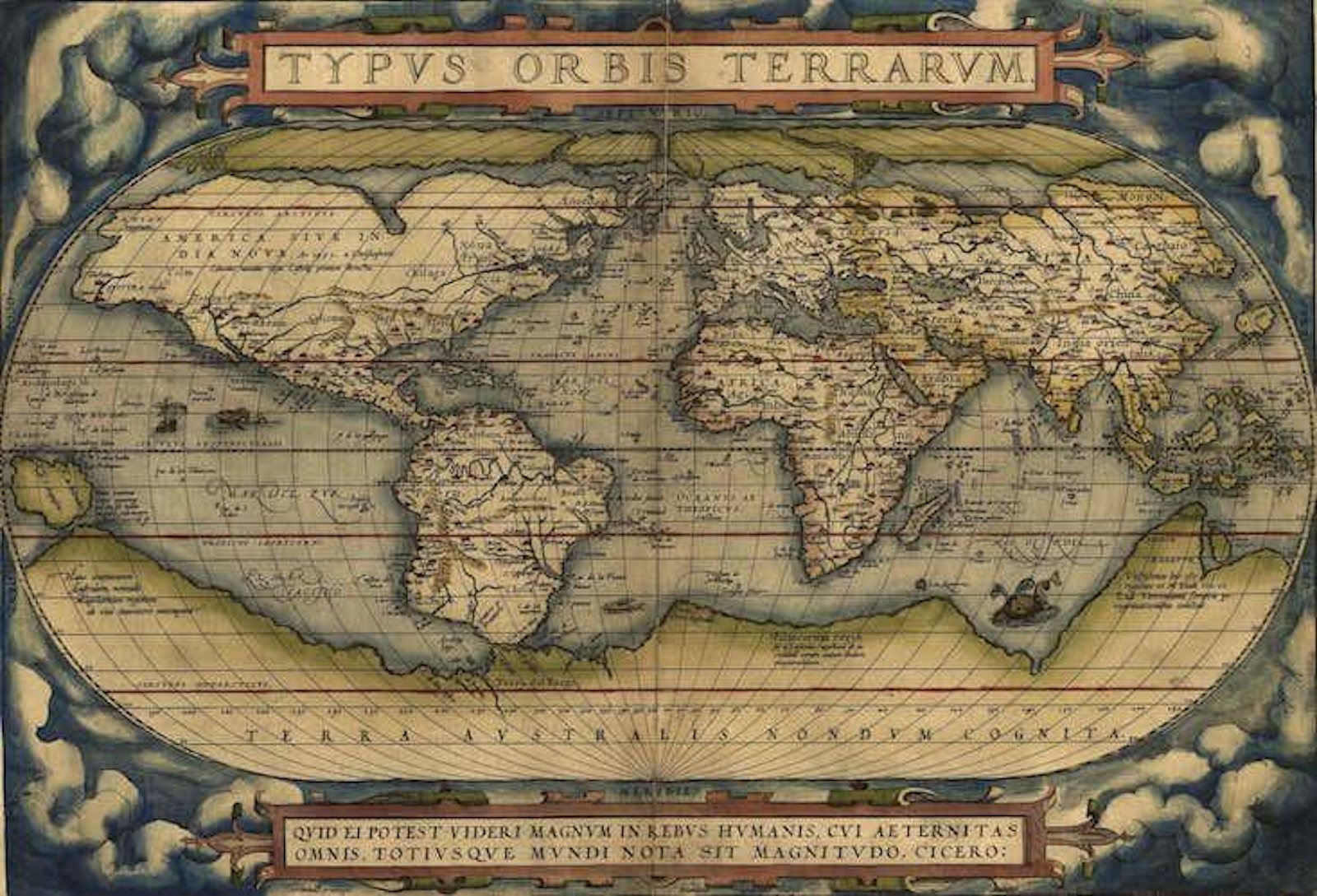

Never before had all cartographic knowledge been compiled together; never before could a reader imagine the totality of the Earth so completely. Simon Garfield writes in On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks that the Theatrum’s “colors were rich and saturated, the lettering (in Latin) elaboratively cursive. The cartouches… burst with vivid additional information.” Within the folio were some 53 beautifully illustrated and colored maps based on the illustrations of 87 cartographers (who were all duly given credit), including the most up-to-date work of Gerardus Mercator. The Theatrum depicted lands from California to Cathay, from the Kara Sea to the Cape of Good Hope. The book was “a huge and instant success,” Garfield writes, “despite the fact it was the most expensive book ever produced.” Though Mercator wouldn’t appropriate the term until 1595, the Theatrum was the first of a type—an atlas.

Asking a Medieval person to imagine the world and their place on it would demand a radically different sort of cognitive map than one a modern person might rely on. This affects pragmatic matters (of navigation and so forth), but also what could be termed poetic ones as well. Philosopher Bertrand Westphal writes in Geocriticism: Real and Fictional Spaces that the “perception of space and the representation of space do not involve the same things,” and this is a crucial point. Ortelius’ atlas gave women and men this new perception of space, a new cognitive map that would allow someone to envision their place and presence on the globe.

Measurement rather than metaphor became a priority.

Despite forgivable errors in the shape of this peninsula or the exact location of that island, what marks the Theatrum is just how correct it actually is. Comparing Ortelius’ atlas to the famed Waldseemüller map of 1507, which first makes mention of the Americas as their own continents, one is struck by how much geographic knowledge had been amassed in the intervening six decades. That earlier map, so named because it was made by the Alsatian cartographer Martin Waldseemüller who was an important influence on Ortelius, presents both North and South America as long thin ribbons floating in an undefined sea, details about the continents limited to the narrow band of the coasts to which European explorers ventured. Even then, there is something that looks a bit like Florida, and another portion that evokes Mexico, so that you can begin to see the proper shapes of the continents take form as if it were a Polaroid picture developing.

The relative reliability of these maps is interesting, not least of which because their makers were concerned with accuracy at all. By contrast, in the Middle Ages maps weren’t necessarily intended to represent the physical world, as Turchi explains, but rather “their aim was, arguably more ambitious: to diagram history and anthropology, myth and scripture.” Medieval maps were from an entirely different genre than those presented by Ortelius. Peter Turchi quips in Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer that “To ask for a map is to say, ‘Tell me a story.’” To condemn Medieval maps is to commit a mistake of genre, for the sort of story that they were telling was not the same as that offered by Ortelius. Medieval maps were concerned less with accuracy than with allegory and theology.

Valerie Flint writes in The Imaginative Landscape of Christopher Columbus that Medieval maps known as mappae mundi were “for the greater part, less geographical descriptions than religious polemics; less maps than a species of morality.” One popular variety of Medieval map to which Flint is referring was something historians called a “T-O Map,” for the shape that it makes in presenting an idealized version of the world. These maps, basing themselves in scriptural precedent, envisioned Jerusalem at the center of the world, with Europe in the lower left quadrant on one side of the straight line of the Mediterranean, Africa in the lower right quadrant, and Asia above the straight line of the Red Sea. The whole of the world appears as a T inside of an O. For Medieval Christians the map expressed certain religious truths about the centrality of the Holy City, the way in which the world geographically divided in a Trinitarian way, and the manner in which a paradisiacal East (for that was the direction of Eden) should be oriented at the top of the picture.

Medieval Europeans, it should be emphasized, didn’t confuse T-O maps for what the world actually looked like. The purpose of such diagrams wasn’t for navigation or commerce, for colonialism or science, but rather to express something symbolic about reality. By the Age of Discovery however, measurement rather than metaphor became a priority. Garfield writes that the “vision of seeing the world anew, and the ability to express it, was what set Waldseemüller, Mercator, and Ortelius apart.” Ortelius’ empiricism, and his concern with ever more correct representations, should rightly strike us as modern. According to Garfield, to examine the Theatrum is to see the perspective of its creator for whom “geographical guesswork and overbearing religion had been banished in favor of science and reason.”

Geographer Yi-Fu Tuan argues in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience that locations “have their factual and their mythical geographies”but it is “not always easy to tell them apart.” Even facts, because they must be filtered by our interpretations, are “necessarily imbued with myths,” he writes. Renaissance map-making may have been more concerned with factual geography, but that doesn’t necessarily mean abandoning the mythical. Ortelius wasn’t the first mapmaker to be concerned with what the coastlines actually looked like, or with making sure that islands were in the right location. But he was the first to gather all of that detailed material in a single place. Those who purchased the Theatrum were not unlike those first seeing The Blue Marble, a photograph of Earth the members of the 1972 Apollo 17 mission took from space.

As with that image, Ortelius’ atlas birthed a new mental geography, a new imagined space. If Medieval thinkers saw themselves as living in a symbolic and allegorical geographic order, then the Theatrum presented the physical world in its totality. The cartographer didn’t prove that the world was round (people already knew that) or that the world was large (they knew that too) but he gave people the mental images necessary to imagine themselves on that large, round globe. Ortelius gave us not disenchantment, but a differing enchantment—a sense of the sheer magnitude of the planet.

Ed Simon is a staff writer at The Millions and an editor at Berfrois. His upcoming book Printed in Utopia: The Renaissance’s Radicalism will be released by Zero Books this summer. Follow him on Twitter @WithEdSimon.