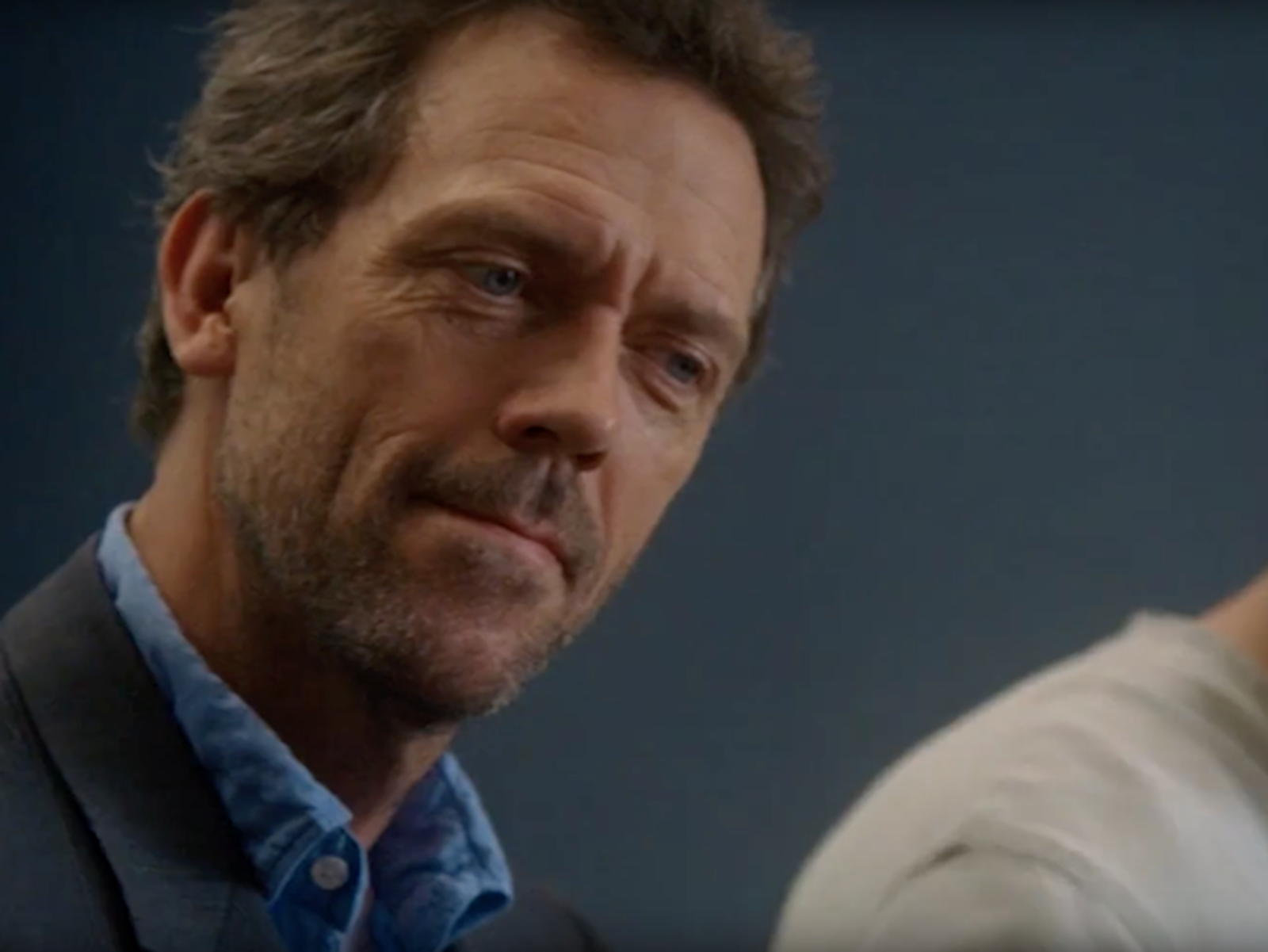

In “Half-Wit,” an episode of House, Gregory House, a brilliant Sherlock Holmes-like doctor (and a decent musician) wheels a piano into a patient’s room. It’s a delightful moment: The patient is a musical savant named Patrick, played by the musician Dave Matthews—a painful muscle contraction in his hand, suffered during a performance, brought him in. House begins to play a piece which, he later tells a colleague, he wrote in junior high. Patrick picks up on the tune and joins House, and they play together, but only until House stops: The good doctor never could figure out what should come next. House watches Patrick, in what seems like rueful astonishment, fill in what was missing. “It’s good,” a colleague tells House, when he’s found replaying Patrick’s addition. House shakes his head. “It’s perfect.”

That ability—of conjuring what is next—is musical expectation, says Jonathan Berger, a professor of music at Stanford, where he teaches composition, music theory, and cognition at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics. An acclaimed composer himself, Berger has explained, in Nautilus, that musical expectations, and the way composers and performers choose to manage them, lie at the heart of the musical experience.

“Daniel Dennett said the mind is an ‘anticipation machine.’ In my mind, music is really a way to test that, a way to sharpen and hone in on that. It’s a lot of the reason music exists,” Berger told Nautilus features editor Kevin Berger (no relation to Jonathan). “Composers are constantly playing off of building expectations and processing those expectations. Realizing the expectations or violating the expectations.” Berger considers musical expectations to be one of the “black holes” of music theory (the other is timbre). “Musical expectations seem to be so fundamentally central to western music at least, if not most music,” he said. “There’s no language. There’s no parlance. There’s no metric. There’s no way to quantify or qualify musical expectations. This has been plaguing me.”

He says one big ah-ha moment he’s had is to consider the correlations between two features of a musical expectation: its strength and specificity. It “opens up this world of thinking about how a composer or a rhetorician will pose an argument, will build it, will present clarity, and then interrupt that clarity.” Introducing confusion, in music or in argument, can work to strengthen the main point, if done deftly. “That’s sort of the idea of rhetoric,” Berger said. “Music, of course, in the 17th, 18th century was the embodiment of the purest state of rhetoric.”

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @brianga11agher.