Amidst life’s profligate swapping and sharing and collaborating, one union stands out: the symbiosis of spotted salamanders and the algae living inside them.

Their uniqueness is no small matter. After all, mutually beneficial relationships between species are legion. Our own genomes are suffused by DNA from other organisms—not inherited from common ancestors, but picked up through the drift of DNA across species. There are cellular mitochondria, the power-generating product of some long-ago meeting, and of course microbiomes, those microbes that account for 90 percent of the cells in animal bodies, and aid in all sorts of physiological processes. Walk through a forest and the trees’ roots are intertwined with co-evolved fungi. A symbiotic carpet lies underfoot.

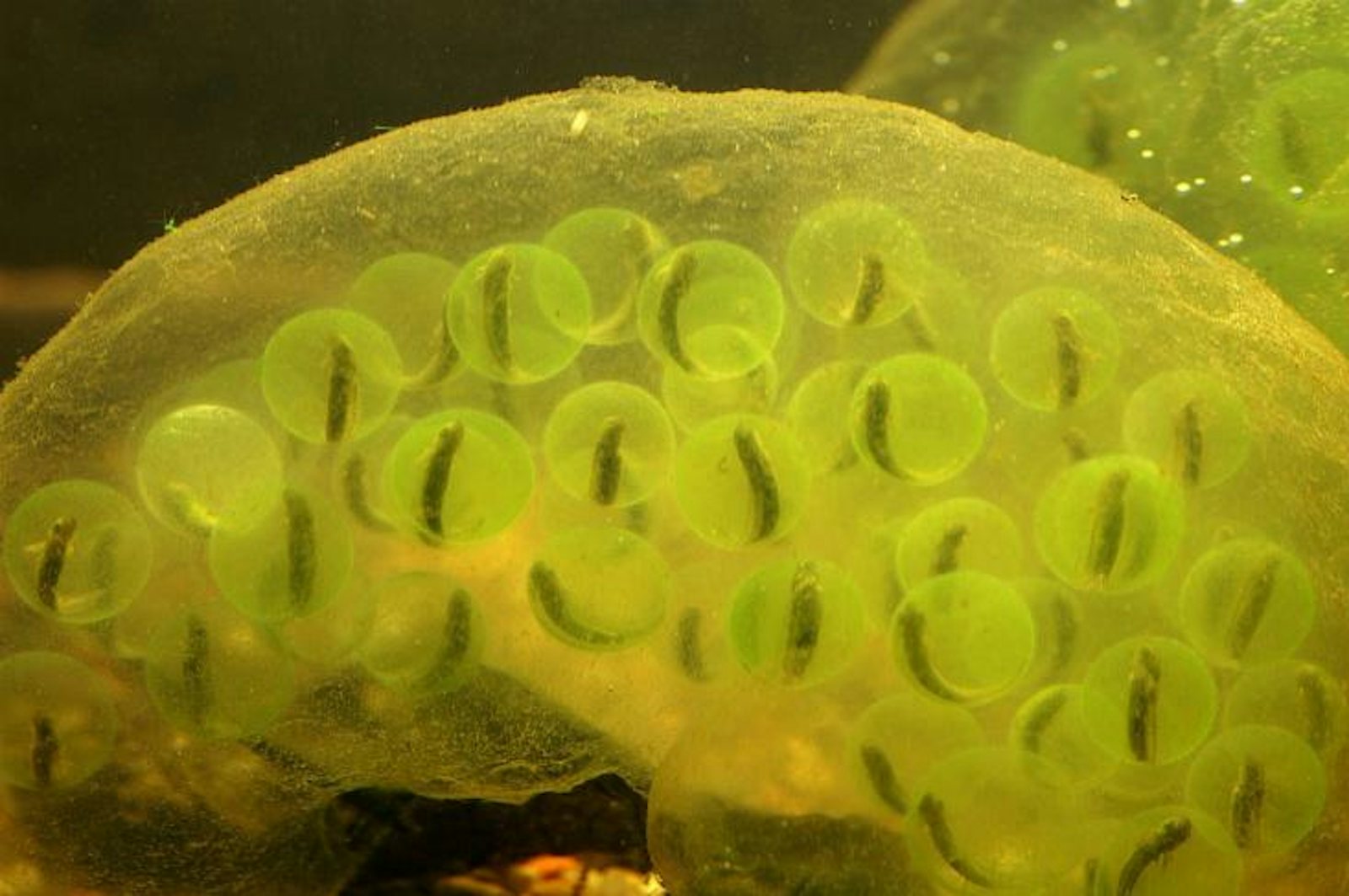

There’s no end to it, yet the spotted salamander—Ambystoma maculatum, to be exact, common to eastern North America—displays something unique. You can see it for yourself: Should you be so fortunate to find spotted salamander eggs in a vernal pool this spring, take a close and gentle look, and note the tiny flecks of green. That’s the algae, Oophila amblystomatis. No other vertebrate has an endosymbiote—an organism living inside it—that is visible to the naked eye*.

One of the first scientists to notice was biologist Henry Orr, who in the late 19th century surmised that the algae did something for embryonic salamanders, though he didn’t know what. By the mid-20th century, researchers had expanded on Orr’s speculations, hypothesizing that algae perhaps fed on cellular waste and in return provided cells with oxygen generated during photosynthesis.

The nature of the symbiosis remained murky, though, and in 2011, researchers found that algae didn’t just reside on cellular surfaces, as Orr and others thought. It lived inside the embryos, literally a part of spotted salamander life from beginning to end. They might even be passed from mother to offspring in a transgeneration act of gardening.

Two years later, another finding further illuminated the relationship (pdf), almost literally. The researchers incubated salamander eggs in water containing a radioactive carbon isotope; when algae photosynthesized, they produced radioactive glucose. The embryos that developed in that water were also radioactive—but not if they were incubated in darkness, when photosynthesis stopped. Algae’s solar-powered activity indeed appeared nourishing.

That hasn’t yet been conclusively demonstrated, but there’s a substantial weight of evidence. More substantial still is the importance of algae to developing embryos. In their absence, embryos tend to develop slowly and less successfully, and are especially vulnerable to infection. Meanwhile, when outside spotted salamanders, O. amblystomatis becomes dormant, forming bunker-like cysts that only open up again when in the presence of their hosts. The species are made for each other.

What might one make of this fact? There are several lessons, one of them immediately practical: atrazine, a common herbicide, may harm salamanders by killing the algae that live within them. Another, more conceptual insight might be taken from the hundred-plus years it’s taken to reach what we know of this union, which researchers now think might be found in many other amphibians and even in fish. As much as we know, we know very little.

And the clearest lesson of all, as evident as the bright green algal flecks and the yellow dots that give spotted salamanders their name, is this: that nature is not simply “red in tooth and claw,” as the old saying goes, a world of vicious competition and ruthless exploitation. It’s one of cooperation, of mutual benefits, of the beautiful ways evolution has found to sustain life in alliance.

* Correction: The article originally said the spotted salamander was the only animal with a visible endysymbiont. But as Dan Clem pointed out in a comment below, there are some invertebrates that also contain photosynthetic algae.

Brandon Keim (@9brandon) is a freelance journalist specializing in science, environment, and culture.