This classic Facts So Romantic post was originally published in September, 2013.

Roughly twice a year, the apparent positions of sun and moon coincide, and a fortunate few observers are treated to a solar eclipse. Watching such an event provides the opportunity to contemplate a strange coincidence: From the surface of Earth, the apparent sizes of the sun and moon in the sky are nearly equal. The sun is almost exactly 400 times larger than the moon, and it’s also almost exactly 400 times farther away.

There is no particular reason why they should appear the same size, and it wasn’t always that way. The moon has been retreating from Earth since the mega-collision that created it, 4.5 billion years ago. We’ve measured its rate of retreat with the help of equipment left on the surface of the moon by Apollo astronauts: It’s presently receding at about 4 centimeters per year. A billion years ago, it would’ve thoroughly covered the sun with every eclipse; now, depending on where the moon is in its elliptical orbit, some eclipses are total, but more are annular, with the moon appearing slightly smaller than the sun, leaving a “ring of fire” surrounding the moon (see image below). Fifty million years from now, the moon will have receded to the point that all eclipses will be annular.

Earth isn’t the only planet with a moon; most planets have them. Are there any other worlds that enjoy the same strange coincidence of apparent sizes? Let’s consider Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos. They are very tiny, making them appear smaller than our moon, but they are much closer to the planet than our moon is to Earth, amplifying their apparent size. And Martians, living half again farther from the sun than earthlings, see a sun only two-thirds as large as ours.

We have actually witnessed Martian solar eclipses, through the eyes of all three Mars rovers. Tiny Deimos looks like little more than a sunspot as it crosses the solar disk (that is, the view of the sun from the surface of Mars). But when closer, larger Phobos transits, it makes the sun look like an eye, with the moon being the eye’s pupil; as Phobos moves across the sun’s disk, the eye’s gaze seems to sweep across Mars’ surface, as though searching for something. Curiosity photographed the searching eye most recently:

Unlike our moon, Phobos is getting closer to Mars with every passing year. (Phobos is in a low enough orbit that it races around Mars faster than the planet rotates. The same tidal forces that make our distant, slower moon recede from us are having the opposite effect on Phobos, gradually bringing it closer to the planet.) In only a few million years, its apparent size may match the sun’s—if tidal forcing does not first tear it apart, forming a ring of small particles orbiting the planet.

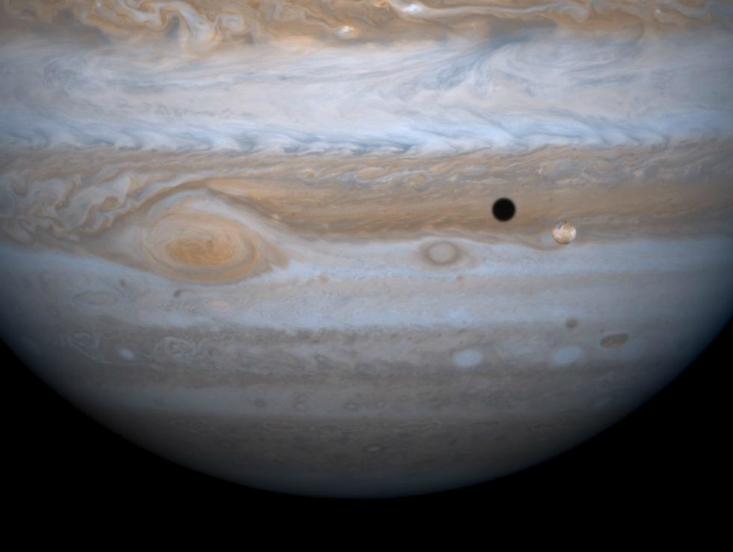

From our earthly viewpoint, we can see that there are solar eclipses visible from the giant outer planets. Twice in each planet’s long orbital year, there are periods when the giant planets’ disks are marred by circular shadows cast by their large moons. If you could stand on the tops of the clouds on those planets, you’d see the sun obscured.

But the giant planets are much farther from the sun than we are, making the sun appear positively puny. If you were to stand atop Jupiter’s cloud tops during an eclipse, the great planet-sized moons would appear gargantuan compared to the sun, completely blotting it out for a significant time. Almost all of their moons are too large and too close; they’d dwarf the tiny sun in their skies. There are a couple, though—Hyperion and Iapetus at Saturn, and Nereid at Neptune—located far enough away, and sufficiently small in size, to mimic Phobos’ searching-eye transits. But at that distance from the sun, the eye would look tiny and much less dramatic.

But there are no planets in our solar system with exactly the right size and location to give a perfect solar eclipse. In that sense, our moon is unique.

Still, if you put enough moons around enough planets, you’re bound to have more sun-moon size coincidences. We now know there are thousands of planets orbiting other suns. We don’t yet know if any of them have moons, but given the profusion of moons in our solar system, it seems very likely that they do. Are there any other intelligent planet-dwellers near other stars, who contemplate a coincidence of sun and moon as we do?

Emily Lakdawalla is senior editor and planetary evangelist for The Planetary Society. She writes about robotic exploration of worlds beyond Earth at planetary.org/blog and as @elakdawalla on Twitter.