I would cut off my right hand if you find it.” That was the guarantee retired Columbia history lecturer Jens Ulff-Møller made that there was no word for “million” in Old English, a medieval predecessor of the language you’re currently reading.

Some Anglo-Saxon writers understood the idea of a million, and they had a term for it: a “thousand thousand.” But, unlike the speakers of most modern languages, they had no single word for that quantity.

Why would that concise word be absent in earlier language? It seems that there was no word for million in Old English simply because its speakers had no great use for it. In the Anglo-Saxon world, no object was made, and few were discussed, in such quantities. Armin Mester, a linguist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, says, “Thousand, one can imagine that there was a use for that, in terms of amount of money. A thousand head of cattle,” he offers. “But not million.”

In millennia past, number words (like one, two, thousand, and million) seem to have been coined progressively rather than all at once. Though the runway of numeracy is infinite, number words, like words in general, were created as needed, as people began thinking and talking about bigger quantities. “I don’t know a language where there would be a word for a large number without there being a use for it,” Mester says. “I’ve never encountered anything like that whenever I’ve looked at the grammar of little-studied languages.”

In the case of English, some new number words were often created by amplifying smaller ones. Etymological dictionaries suggest that our word “thousand” originated as a magnification of a lesser one: “hundred.” The Oxford English Dictionary relates that the first half of “thousand” is rooted in the Indo-European “tus”—meaning “multitude” or “force”—while the latter half is related to that smaller number. As two British mathematicians put it in The Book of Numbers, “A ‘thousand’ is literally a ‘strong hundred.’” The composite nature of the word makes it plausible that “thousand” emerged from “hundred,” as the need for it grew. A hundred was perhaps enough to tally the members of our group. But that big clan over the hill? Their ranks were deep enough for a “strong hundred,” at least.

“Taxi” is sometimes credited as a universal word, as are variants of “mom” and “dad,” but “million” may not be far off.

When people in Great Britain began speaking Old English, “thousand” was likely the biggest number word available. (Back then it was spelled “þusend,” the first letter of which is the now-disused “thorn.”) The word is used four times in Beowulf, and numbers as great as “thirty hundred thousand”—that is, three million—appear in a collection of sermons and narratives written in the 10th century.

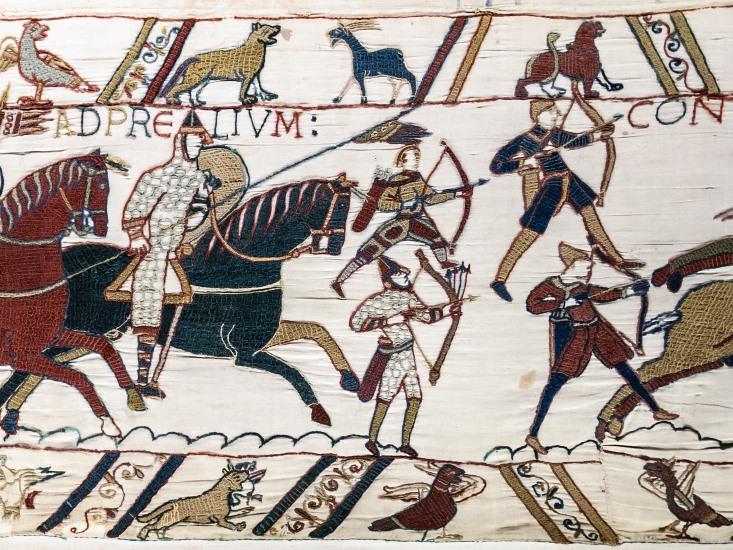

The English language as we know it now makes an especially strong case for the idea of progressive numbering, given the language’s numerous word infusions from other languages. When William the Conqueror, who spoke a dialect of French, invaded England in 1066, he paved the way for a wealth of French words to enter English over the next few centuries. That infusion of vocabulary was transformative enough for modern linguists to draw the line here between Old English and Middle English, the language of Chaucer.

One of the later imports was “million,” which began appearing in the 14th century in sources including a religious poem and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Until then, the sum could only be expressed by combining existing word numbers, as in the case of “þusend þusend.” Now it had its own shorthand. “The innovation of the word million is not in the concept itself, but rather in the creation of a single word for it (to replace the earlier somewhat unwieldy phrases)”, writes Anthony Esposito, associate editor of etymology at the Oxford English Dictionary.

Just like “thousand,” this was a new number born of an existing one. In the European world, the word for million was formed by squaring the word for thousand with a simple suffix. In modern Italian, these words are “mille” and “milione,” and today a similar pair of words exist in every Romance language.

By adopting this new word, English speakers were better prepared to discuss greater sums in a more complicated world. Murray McGillivray, who teaches Old English at the University of Calgary, says “million” would not have been too useful in the small economy and modest land holdings of pre-feudal England. Million was “a late medieval concept, [used] to kind of total up the whole realm,” he says.

“Million” likely played a role, as well, in the financial flourishing that came with the early Renaissance. An Italian mathematician, the famous Fibonacci, helped spread the use of Hindu-Arabic numerals in the Western world in 1202. This system uses decimal place values and zero, two important concepts missing from the Roman numeral system used in Europe at the time. Such mathematical innovations were “important for enabling large scale economies in societies,” Ulff-Møller wrote in a recent paper. Sure enough, Fibonacci’s fellow Italians would later invent the check, joint stock companies, and central banking.

Perhaps because of its usefulness, the word “million” spread to Germanic and Slavic tongues, and eventually into ones as diverse as Turkish, Somali, and Arabic. “Taxi” is sometimes credited as a universal word, as are variants of “mom” and “dad,” but “million” may not be far off.

The idea of progressive numbering may not hold up as well in some other cultures, however. Ancient Egypt, in fact, had a hieroglyph for “million,” and ancient Sanskrit had words for massive numbers progressing by multiples of ten, like padma (one billion), kharva (10 billion), and nikharva (100 billion). But in certain linguistic lineages at least, number words were spawned by the same impetus that drives the creation of most words: necessity.

In recent decades, modern science, expanding into ever bigger and smaller realms, has provided the push for new number words and prefixes. Now we have no trouble referring to terabytes of data or light waves that vibrate on the order of femtoseconds. Until Google starts storing many googolplexes of bits, the number words we have now should be plenty.

Pierre Bienaimé is a writer and musician based in New York. He’s on Twitter as @ScribblerSounds.