Our

Universe is vast and mostly empty. Even if many of the billions of

planets we suspect are out there have life, most of the cosmos is

uninhabitable, and those worlds are unreachable by any means we know.

That’s just within our galaxy, which is one of about 100 billion in

the part of the universe we can see (the “observable universe”),

which itself is only part of a bigger universe, which may extend

infinitely in space. Then there’s the possibility, arising as a

consequence of several theories, that that universe is but one part

of a multiverse. All these things understandably can lead to feelings

of insignificance.

That’s

the entry point Adam Frank used for his recent Nautilus post: Is this universe at all special, especially in light of the

possibility that it’s just one small part of a multiverse?

If our observable universe is one of many, but the only one that can

support life, does that somehow restore us to special status? Frank

connects this question with the Copernican principle, a concept

central to modern cosmology.

In the

four centuries since his major published astronomical work,

Copernicus has become a symbol for scientific revolution: changing

the way we think about the world from received wisdom to empirical

knowledge. The

Copernican principle

is actually an extension of Copernicus’ ideas rather than something

he wrote. The central pillar of this idea is that not only is Earth

not the center of the solar system, it doesn’t occupy a privileged

position in the Universe as a whole. A bug-eyed alien astronomer from

planet Gleethnorp in a distant galaxy would count more or less the

same number of galaxies in the observable universe that we do,

scattered in more or less the same way. What

if we wanted to look at galaxies not from planet Gleethnorp but from

an entirely different “pocket” universe—would things look the

same there as they do in our local cosmos? It’s unlikely. Many

multiverse models include the idea that the other pocket universes

separate from ours might have different physical parameters, meaning

they might be completely unable to support life. The bit of the

cosmos we inhabit has just the right values for certain physical

properties—the relative strengths of forces, for example—for life

to exist. The question of why our universe seems so perfectly set up

for us to be here is called the “fine-tuning” problem. A slight

alteration to some parameters would result in a universe incapable of

bearing life, or devoid even of stars and galaxies. That is still in

keeping with the Copernican principle, since other pocket universes

aren’t connected to ours, and no position within any of them is

special. Nevertheless, as Frank wants to know, is our

pocket universe special, somehow privileged?

We have no more evidence for multiverses than we have evidence for life beyond Earth—though it’s reasonable to think both exist.

The

multiverse is profoundly uncomfortable to many people, but it’s not

just an idea (or a “meme,” as Frank puts it).

Inflation—the extremely rapid expansion of our cosmos during its

very earliest moments—almost certainly would produce regions that

have never been in contact with the one containing our observable

Universe. In that sense, we get a multiverse as a consequence of the

theory with no extra assumptions, as each of those pockets would be a

parallel universe, inaccessible from ours, and possibly having

different physical parameters than ours. That could solve the

fine-tuning problem, if we can establish what the possible range in

physical properties could be between the different pocket universes.

The multiverse could include an enormous number of pocket universes

with different parameters, and we just happen to be in one where

stars, and star-nosed moles, can exist.

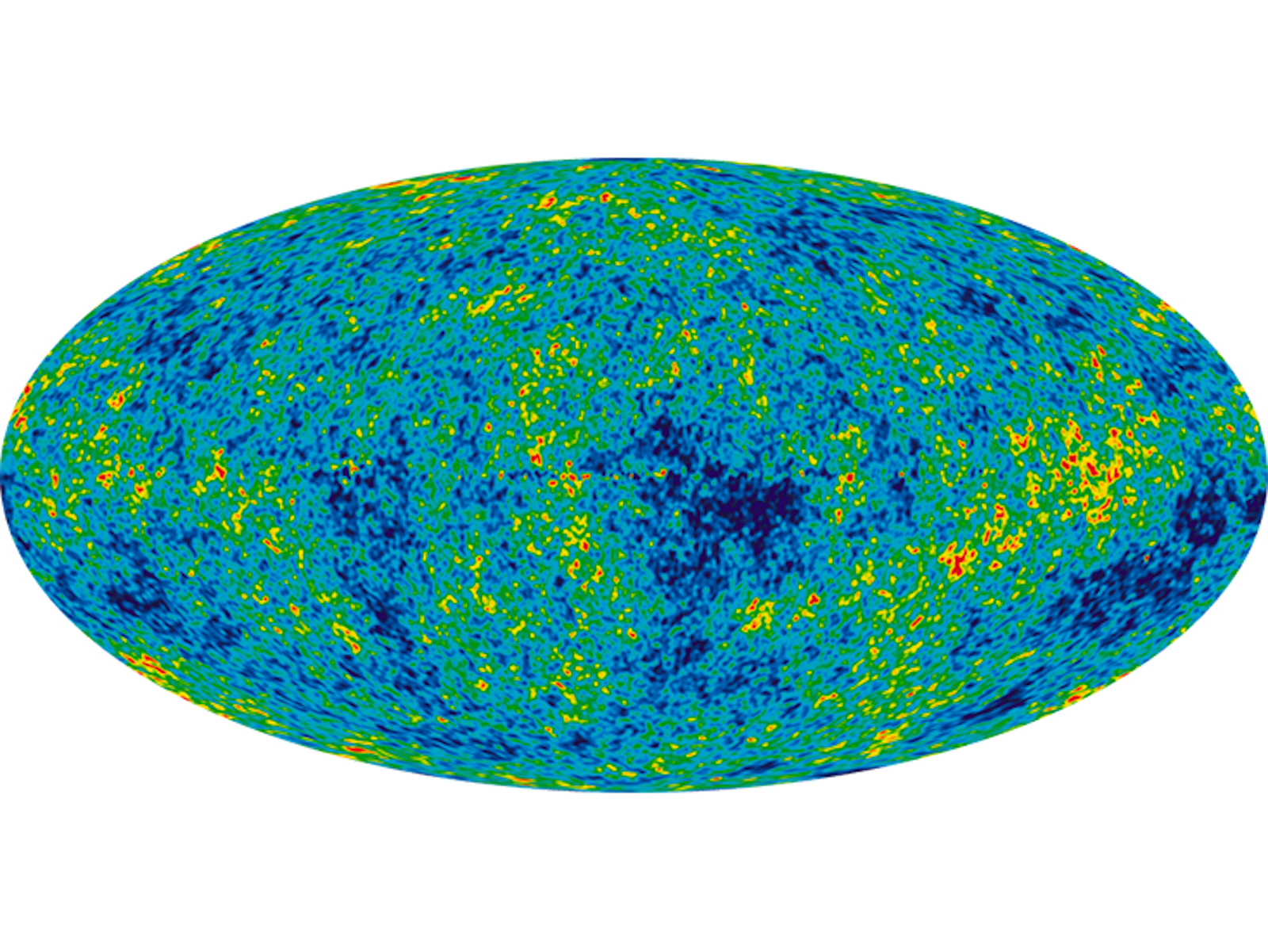

The

best evidence for inflation comes from the cosmic microwave

background (CMB, seen at the top of the post): the radiation left over from when the observable

Universe became transparent, about 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

The temperature of this radiation barely fluctuates over the entire

sky, even though regions on opposite sides of the observable Universe

were never in contact if the cosmos expanded at the rate we see

today. Inflation explains that those regions were

in contact when the Universe was very young, and the rapid expansion

carried them far apart before the CMB formed. Inflation isn’t a dead

certainty—most cosmologists accept that it probably happened, as

observations have mostly ruled out its alternatives, though we need a

new type of measurement to see its effects more directly.

A

multiverse also arises in string theory if you consider each of the

10500

or so possible “vacuum states”—known as the “string theory

landscape”—to be a separate pocket universe. In either the

inflationary or stringy case, the existence of pocket universes is a

question of physics, not metaphysics (philosophy about

existence)…though as with the

question of what came before the Big Bang,

it may be hard to establish their existence. Personally, I’m not a

fan of the string theory landscape (and neither are all string

theorists), but I’ve reluctantly come to accept that the inflationary

take on the multiverse is probably real—with the usual scientist’s

disclaimer that I’m willing to be convinced if the evidence

contradicts me. In any case, one need not invoke string theory to see

the possibility of a multiverse in the observable universe we have.

We

know that the universe is capable of supporting life, and that any

physical parameters must be consistent with that obvious fact. Beyond

that, we can’t go yet: We have no more evidence for multiverses than

we have evidence for life beyond Earth—though it’s reasonable to

think both exist. The uncomfortable possibility is that there are other pocket

universes, but we’ll only ever know about them indirectly. That

doesn’t make them any less real, just discomforting.

Fine-tuning

is a bona fide puzzle, and the multiverse may not solve it, depending

on what parameters are possible for other universes. Even a large

number of parallel pocket universes doesn’t lead to infinite

possibilities. (If you could check all of the 10500

possible universes in the string theory landscape, you’ll still

never find a a low-mass object holding a high-mass object in orbit,

or a universe where am I a fan of the Star

Wars

prequels.) So without knowing more about the finite possibilities for

other universes—or indeed if they exist—it’s impossible to say

whether our particular universe is special.

In

any case, metaphysics didn’t invent the multiverse, and it won’t

solve the fine-tuning problem.

Matthew Francis is a physicist, science writer, public speaker, educator, and frequent wearer of jaunty hats. I’m currently writing a book on cosmology, with working title Back Roads, Dark Skies: A Cosmological Journey.