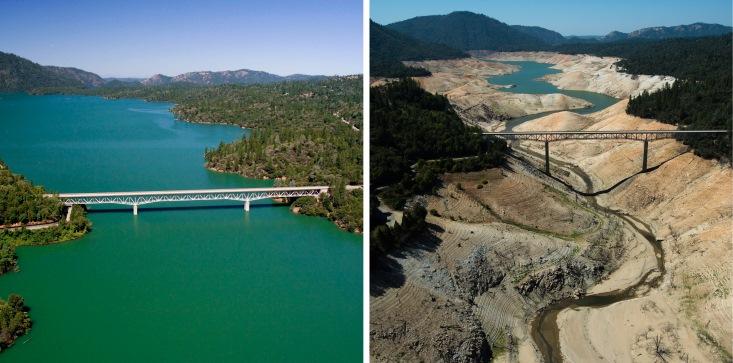

California is thirsty. The state is in its fourth year of a drought that is especially severe, by any measure. For instance, an April 1 snowpack measurement, a key indicator of surface-water supplies, was lower than any year on record, going back at least to 1950. Dry statistics aside, you can grasp the scope of the problem in an instant with the many before-and-after photos of California’s reservoirs and waterways. What were once tree-lined shores of large lakes are now high ridges overlooking swathes of exposed, dried lake bed and the muddy remnants of formerly flush basins. The land itself is thirsty.

If that’s enough to make you want a stiffer drink that mere tap water, you’re not alone: Californians consume a combined seven and a half gallons of wine and craft beer per adult each year, two drinks that are primarily homegrown and rely on the state’s water.

And speaking of homegrown, no discussion of Californian intoxicants would be complete without a nod to marijuana. Although its cultivation exists in a legal gray area—grown for loosely defined medical reasons, it is not fully legalized in California as it is in Colorado or Washington State—marijuana is now estimated by some to be the state’s largest cash crop, worth more than $31 billion per year. The demand for and lenient attitude toward pot have driven an explosion in outdoor grow operations that are having a direct impact on the already low water levels in streams and rivers.

The human thirst for intoxication is relatively insensitive to external conditions, but if anything, it only increases in the face of stressors. If the drought continues, vintners, pot growers, and brewers will have to learn to adapt. Here’s how the Golden State’s trinity of vices are coping with the drought—and perhaps an arid long-term future.

Wine

The thing about grapevines is that they evolved to deal with dry conditions, says P.J. Alviso, director of estate viticulture at Napa Valley’s Duckhorn Wine Company. There are no irrigation lines in nature, and vines became adept at living through dry summer months on the faint moisture left in the soil during winter precipitation. In fact, when it comes to fine wine grapes, the gradual drying of the soil through summer and into fall is what triggers the hormonal messages that make vines bring their fruit to maximum ripeness, which in turn yields more concentrated and better flavors in the resulting wine. In that regard, the past three years of drought have actually been a boon to high-end wine producers in the region.

“We want that stress, we want that concentration, so we want to limit the water to the vine any way we can,” Alviso says. “If that happens naturally, we don’t necessarily see that as a negative.”

In much of Europe, irrigating vineyards has at times been illegal, and even the vines under Alviso’s care in Napa, Sonoma, and Mendocino Counties (California’s traditional wine country) typically require no more than 50 gallons of water irrigation per plant per year. That’s a far cry from the gallon of water it takes to produce a single almond, the current bugbear in the California water debate.

But while high-end wine producers like Duckhorn—a bottle of their 2011 Cabernet Sauvignon will set you back $70—benefit from more flavorful wine, the producers of inexpensive bulk wines in California’s Central Valley may soon begin feeling the pinch if water is further restricted. Not only is water more scarce in the Central Valley to begin with, but the operations there are looking to increase rather than decrease their water supply. Growers that produce grapes for cheap wines aren’t interested in concentration and perfect ripeness, but in growing the most grapes possible. In 2005 Central Valley vineyards produced an average of 12 tons of grapes per acre, according to the California Agriculture journal, while ritzier North Coast vineyards had only 4 tons per acres. When growing for cheaper wines, “you want to be as big and plump and juicy as possible, where we are coming at the other end,” says Alviso.

If the drought continues, it will be the purveyors of jug wines and other inexpensive labels on the bottom shelf that will suffer the most as their production levels fall. At the same time, it may be a boon to consumers, who could get a significantly more flavorful wine for a few dollars more.

As for Napa Valley, Alviso says that with producers’ focus on quality over quantity and a water table that has been stable for the past 20 years, surviving a longer drought is not a big problem. “I’ve seen those megadrought studies … based on tree rings. There was a time in the early 1500s where it didn’t rain for 10 years or something. If that happens, I think we all have to get really creative,” he says. “But we’re really good at getting creative.”

Marijuana

It turns out it is not the patrician wine industry or the hipster-oriented craft brew culture that are most taxing California’s drought stricken water system. That honor falls, with a full twist of irony, on marijuana, hippy and “green” associations and all. The weed is both thirsty and dirty.

A single pot plant can slurp as much as 22.7 liters—just less than 6 gallons—of water per day. That demand for water was manageable when growers mainly limited their operations to between one and 100 plants grown indoors or on their property, per California law. But as demand has increased, so have the number of very large, often illegal grows in the dense forests of Mendocino, Humboldt, and Trinity counties—the so-called Emerald Triangle—where growers who often trespass on public lands are sucking some streams dry to feed thousands of marijuana plants. A recent study by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife concluded that the demand for water to grow pot is greater than the total amount of water in the streams of some watersheds during the dry season, presenting a potentially lethal threat to salmon and steelhead trout.

“When they pump water out of the watersheds and the rivers, there will not be enough water left for the fisheries,” says Mendocino County Supervisor Tom Woodhouse. “When we do salmon restoration, we are kind of shooting ourselves in the foot if people are just draining it with illegal grows. Plus the price of pot is going down, so they double the amount that they grow and then that raises the water demand.”

Large outdoor marijuana operations also leak pesticides, fertilizer, fuel, and other detritus into streams. This problem existed prior to the drought, but is certainly being exacerbated by it, according to North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board assistant executive officer Shin-Roei Lee.

The board is currently working on a regulatory scheme to mitigate the effect of marijuana on the state’s water supply. It would require marijuana growers to purchase a water-use permit based on the size of their operation and to commit to a set of best-management practices, though Lee admits that with marijuana still illegal under federal law, it could be difficult to enroll growers. “They worry that if they enroll, people will know where they are and how much they are growing,” she says. As far as the state water board is concerned, pot isn’t so much an illegal drug as a thirsty crop. “We just want to protect the water quality and the habitat.”

Lee is optimistic that there are enough legal growers who would be willing to participate to make a marked improvement in water quality. “There are very conscientious growers that are trying to do it right, growing with the least amount of pesticides and fertilizers,” she says. “They welcome this system they can enroll under.”

Beer

Beer has an advantage: The majority of the grains and hops used by the state’s more than 200 craft breweries are grown elsewhere, making no demands on California’s water system at all. There is some water involved in malting and brewing those grains, as well as cleaning equipment, but not as much as you might think. The total demand from brewers amounts to about 93 million gallons a year, according to estimates given by Dr. Jeffrey Mount of the Public Policy Institute of California in a talk at the California Craft Beer Association. That’s equivalent to the water used by 12,000 people or 640 acres of almonds. Put in context, there are more than 800,000 acres of almonds being grown in the Golden state, making the entire California beer industry’s water needs a mere drop in the ocean reserved for nuts.

But if beer is having little effect on the drought conditions, continuing drought conditions could begin to affect the quality of the beer. The mineral content of the water used to brew beer is an important component of its flavor profile, and can even be essential to certain styles. Petaluma-based craft brewer Lagunitas sources its water from the nearby Russian River, which has the perfect mineral profile for their purposes, according to Karen Hamilton, the company’s director of communications. That water is plentiful for now, but Lagunitas is preparing for the possibility that things might change. If the brewer had to switch to city water, “We would need to treat the water to make it the same quality as the water we use now, but we are prepared for that,” Hamilton says. She also reports that they have changed their operations to conserve river water. “We have reduced the amount of water used to brew down to three to one—that is, three gallons of water to brew one gallon of beer,” she says, down from four to one in 2012. Lagunitas plans to get the ratio further down to 2.5 to one with new wastewater-recycling technologies.

As the drought continues on, more and more industries may be forced to find similar ways to save.