Much like its creator, Karl Weierstrass’ monster came from nowhere. After four years at university spent drinking and fencing, Weierstrass had left empty handed. He eventually took a teaching course and spent most of the 1850s as a schoolteacher in Braunsberg. He hated life in the small Prussian town, finding it a lonely existence. His only respites were the mathematical problems he worked on between classes. But he had nobody to talk to about mathematics, and no technical library to study in. Even his results failed to escape the confines of Braunsberg. Instead of publishing them in academic journals as a university researcher would, Weierstrass added them to articles in the school prospectus, baffling potential students with arcane equations.

Eventually Weierstrass submitted one of his papers to the respected Crelle’s Journal. While his previous articles had made barely a ripple, this one created a flood of interest. Weierstrass had found a new way to deal with a fiendish class of equations known as Abelian functions. The paper only contained an outline of his methods, but it was enough to convince mathematicians they were dealing with a unique talent. Within a year, the University of Königsberg had given Weierstrass an honorary doctorate, and soon afterward the University of Berlin offered him a professorship. Despite having gone through the intellectual equivalent of a rags to riches story, many of his old habits remained. He would rarely publish papers, preferring instead to share his work among students. It was not just the publication process he had little regard for: He was also not afraid to target mathematics’ sacred cows.

Weierstrass soon took aim at the research of Augustin-Louis Cauchy, one the century’s most eminent mathematicians. Much of Cauchy’s work focused on calculus and rates of change (or “derivatives”). He had created what was in essence a calculus dictionary, specifying the subject’s most important concepts. But when Weierstrass read its definitions, he found them to be wordy and vague. There was too much hand waving, and not enough detail.

If Newton had known about such functions, he would have never created calculus.

He decided to revise Cauchy’s dictionary by replacing the prose with logical conditions. Chief among this early work was the redefinition of a derivative. To calculate the gradient of a curve at a certain point—and hence its rate of change—Isaac Newton had originally considered a line that passed through the point of interest and a nearby point on the curve. He then moved that nearby point closer and closer, until the slope of the line was equal to the gradient of the curve. But it was difficult to define the concept mathematically. What dictated whether two points were “close” to each other?

In Cauchy’s verbose definition, the gradient would “approach indefinitely to a fixed value, in a manner so as to end by differing from it by as little as one wishes.” Weierstrass did not think this was clear enough. He wanted a more practical definition, so decided to convert the concept into a formula. Rather than manipulating abstract ideas, mathematicians would instead be able to rearrange equations. In doing so, he was laying the foundations for his monster.

At the time, mathematicians drew much of their inspiration from nature. When Newton first developed calculus, he’d been inspired by the physical world: the trajectory of a planet, the swinging of a pendulum, the motion of falling fruit. This thinking led to a geometrical intuition about mathematical structures. They should make sense in the same way that a physical object would. As a result, many mathematicians concentrated on “continuous” functions. Conceptually, these are functions that can be drawn without taking pen from paper. Plot the speed of a falling apple over time and it will be a solid line; there will be no gaps or sudden jumps. A continuous function was, it was thought, a natural one.

Conventional wisdom held that for any continuous curve, it was possible to find the gradient at all but a finite number of points. This seemed to match intuition: A line might have a few jagged bits, but there would always be a few sections that were “smooth.” The French physicist and mathematician André-Marie Ampère had even published a proof of this claim. His argument was built on the “intuitively evident” fact that a continuous curve must have sections that increase, decrease, or remain flat. Which meant that it must be possible to calculate the gradient in these regions. Ampère did not think about what happened when the sections became infinitely small, but he claimed that he didn’t need to. His approach was general enough to avoid having to consider things that were “infiniment petits.” Most mathematicians were happy with his reasoning: By the middle of the 19th century, almost every calculus textbook quoted Ampère’s proof.

But during the 1860s, rumors started circulating about a strange creature, a mathematical function that contradicted Ampère’s theorem. In Germany, the great Bernhard Riemann told his students that he knew of a continuous function that had no smooth sections, and for which it was impossible to calculate the derivative of the function at any point. Riemann did not publish a proof, and neither did Charles Cellérier at the University of Geneva, who—despite writing that he’d discovered something “very important and I think new”—stuffed the work into a folder that would only become public after his death decades later. Yet if the claims were to be believed, it meant a threat to the very foundations of calculus was forming. This creature threatened to tear apart the happy relationship between mathematical theory and the physical observation on which it was based. Calculus had always been the language of the planets and stars, but how could nature be a reliable inspiration if there were mathematical functions that contradicted the central ideas of the subject?

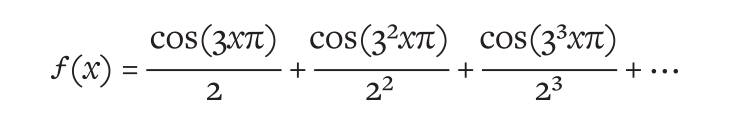

The monster was finally born in 1872, when Karl Weierstrass announced that he had found a function that was continuous and yet not smooth at any point. He had constructed it by adding together an infinitely long sequence of cosine functions:

As a function, it was ugly and awkward. It was not even clear what it would look like when plotted on a graph. But that didn’t matter to Weierstrass. His proof consisted of equations rather than shapes, and this was what made his announcement so powerful. Not only had he created a monster, he’d built it from concrete logic. He had taken his new, rigorous definition of a derivative and shown it was impossible to calculate one for this new function.

The result threw the mathematics community into a state of shock. The French mathematician Émile Picard pointed out that if Newton had known about such functions, he would have never created calculus. Rather than harnessing ideas about the physics of nature, he would have been stuck trying to clamber over rigid mathematical obstacles. The monster also began to trample over previous research. Results that had been “proven” started to buckle. Ampère had used the vague definitions favored by Cauchy to prove his smoothness theorem. Now, his arguments began to collapse. The vague notions of the past were hopeless against the monster. Worse, it was no longer clear what constituted a mathematical proof. The intuitive, geometry-based arguments of the previous two centuries seemed to be of little use. If mathematics tried to wave the monster away, it would stand firm. With one bizarre equation, Weierstrass had demonstrated that physical intuition was not a reliable foundation on which to build mathematical theories.

Established mathematicians tried to brush the result aside, arguing that it was awkward and unnecessary. They feared that pedants and troublemakers were hijacking their beloved subject. At the Sorbonne, Charles Hermite wrote, “I turn with terror and horror from this lamentable scourge of functions with no derivatives.” Henri Poincaré—who was the first to call such functions monsters—denounced Weierstrass’ work as “an outrage against common sense.” He claimed the functions were an arrogant distraction, and of little use to the subject. “They are invented on purpose to show our ancestors’ reasoning is at fault,” he said, “and we shall never get anything more out of them.”

Many of the old guard wanted to leave Weierstrass’ monster in the wilderness of mathematics. It didn’t help that nobody could visualize the shape of the animal they were dealing with—only with the advent of computers did it become possible to plot it. Its hidden form made it hard for the mathematics community to grasp how such a function could exist. Weierstrass’ style of proof was also unfamiliar to many mathematicians. His argument involved dozens of logical steps, and ran to several pages. The trail of ideas was subtle and technically demanding, with no real-life analogs to guide the way. The instinct was to avoid it.

But monsters have a habit of finding their way in from the cold. Indeed many concepts that now seem obvious, even essential, were once monsters. Negative numbers were shunned by mathematicians for centuries. The ancient Greeks, who dealt chiefly with geometry, saw no need for them. Nor did the medieval academics who adopted Greek ideas. The shadow of this monster will occasionally still appear today, such as when a child asks why multiplying two negative numbers together produces a positive one. But overall the beast has been tamed; nobody would dream of exiling it again.

In a similar fashion, Weierstrass’ monster began to find acceptance. In 1904, Albert Einstein introduced physicists to the idea of “Brownian motion”: Particles in a liquid, he said, follow a random path because fluid molecules are constantly knocking them around. The collisions are so frequent (more than 1021 per second) that no matter how good the microscope, or how detailed the observation, the trajectories are never smooth. At the practical level, it is not possible to find a derivative. If researchers wanted to work with such problems, they would need to confront Weierstrass’ monster—and that is exactly what Einstein did. His theory for Brownian motion used functions that were infinitely jagged. It set a longstanding precedent: Physicists have used non-smooth functions as a proxy for Brownian motion ever since.

Once it became clear that the so-called “Weierstrass function” was actually quite useful, researchers began to develop ways to handle non-smooth functions gracefully. Rather than trying to analyze the path of a single particle in a liquid, they would look at the average behavior of many particles. How far were they likely to travel? When might they reach a given point? Outside of Brownian motion, mathematicians also started to rethink the basic tools of calculus. Rates of change had always been defined in terms of distances, and areas under a curve measured geometrically. But when functions were not smooth, these ideas did not make sense.

At the University of Tokyo, Kiyoshi Itō found a way around the problem by thinking in terms of probabilities. It was an unorthodox, not to mention risky, tactic: During the 1940s, hardly anyone viewed probability theory as a rigorous subject. Yet Itō persevered. He treated functions like random processes, and translated Weierstrass’ definitions into a new, probability-based language. Two random processes were “close” together, he said, if the expected outcomes were the same. He introduced a method for handling a mathematical function that depends on a non-smooth quantity—like Brownian motion—rather than a more traditional variable, like distance. Using his new methods, he derived “Itō’s Lemma” to calculate how such a function changes over time.

By the 1970s, Itō’s work had blossomed into a whole new area of mathematics, called stochastic calculus (mathematicians like calling things that are random “stochastic”). It came with a whole new set of tools and theorems, just as calculus had. Today, stochastic calculus is used to study all sorts of phenomena, from neurons firing in a brain to diseases spreading through a population. It is also at the heart of financial mathematics, where it helps banks estimate option prices. It can account for the bumpy behavior of a stock price, and hence reveal how the value of an option changes over time. The resulting equation, which is known as the Black-Scholes formula, is now used on trading floors around the world. Yet Itō was always puzzled when he won plaudits from bankers. As a pure mathematician, he hadn’t expected his work to become famous for its applications.

The $1 million prize remains unclaimed. In many ways, it is a ransom.

Weierstrass’ monster shook things up in geometry too. At the end of the 19th century, Swedish mathematician Helge von Koch had become interested in the idea of non-smooth functions, but he wanted to see their shape. He set out to build a shape (rather than a function) that was nowhere smooth, and hence show that the same monsters were lurking in both algebra and geometry. He might not be able to draw the Weierstrass function, but he would be able to picture its cousin. Working on the problem while hopping from one temporary job to another as a junior professor, von Koch found his creature in 1904. Constructed by taking an equilateral triangle, then adding three smaller triangles to each side, and continuing to do so indefinitely, it was a geometric shape that was continuous but had no derivatives. The shape’s distinctive appearance meant it soon became known as the “Koch snowflake.”

Koch had succeeded in extending Weierstrass’ monster beyond the world of equations and functions. But there was something else noteworthy about his result. Upon closer inspection, it turned out that his snowflake had a curious self-similarity: Magnify one particular section of the snowflake and it would look similar to the zoomed-out shape. Many years later, it would become apparent that the Weierstrass function had the same property.

As time went on, this self-similarity began cropping up in all sorts of places. It would take Benoît Mandelbrot’s seminal work during the 1980s to popularize the idea of “fractal” objects, which had shapes that were repeated at smaller and smaller length scales. From coastlines and clouds to plant and blood vessels, mathematicians discovered that fractals were ubiquitous in nature. Like Koch’s snowflake, none were smooth. How could they be? If the shape had smooth sections, the pattern would disappear when magnified sufficiently. As Koch had found, the simplest way to obtain a non-smooth shape was to construct a fractal object. Perhaps it was inevitable that Weierstrass’ work would guide mathematicians towards self-similar patterns, introducing researchers to a world of intricate, beautiful structures.

Weierstrass’ monster continues its work in the present day. The Navier-Stokes equations describe the motion of a fluid and underpin modern fluid dynamics and aerodynamics, driving everything from aircraft design to weather prediction. However, although they were first developed in the 1840s, mathematicians still do not know if they can always be solved. In 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute offered a $1 million prize to anyone that could show that the equations always have smooth solutions—or find an example to the contrary. The problem is considered among the six most important outstanding problems in mathematics because, despite the widespread use of the Navier-Stokes equations, mathematicians do not know whether the equations always produce physically plausible results. The $1 million prize remains unclaimed. In many ways it is a ransom, encouraging mathematicians to hunt for troublesome monsters.

From fluid dynamics to finance, creatures like the Weierstrass function have challenged our ideas about the relationship between mathematics and the natural world. Mathematicians around the time of Weierstrass used to believe that the most useful mathematics was inspired by nature, and that Weierstrass’ work did not fit into that definition. But stochastic calculus and Mandelbrot’s fractals have proven them wrong. It turns out that in the real world—the messy, complex real world—monsters are everywhere. “Nature has played a joke on the mathematicians,” as Mandelbrot put it. Even Weierstrass himself fell victim to the trick. He created his function to argue that mathematics should not be based only on physical observations. His followers believed that Newton had been constrained by real-life intuition and that, once free of these limitations, there were vast, elegant new theories to be discovered. They thought that mathematics would no longer need nature. Yet Weierstrass’ monster has revealed the opposite to be true. The relationship between nature and mathematics runs deeper than anyone ever imagined.

Adam Kucharski is a research fellow in mathematical epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2014 Nautilus Quarterly.