The invention of religion is a big bang in human history. Gods and spirits helped explain the unexplainable, and religious belief gave meaning and purpose to people struggling to survive. But what if everything we thought we knew about religion was wrong? What if belief in the supernatural is window dressing on what really matters—elaborate rituals that foster group cohesion, creating personal bonds that people are willing to die for.

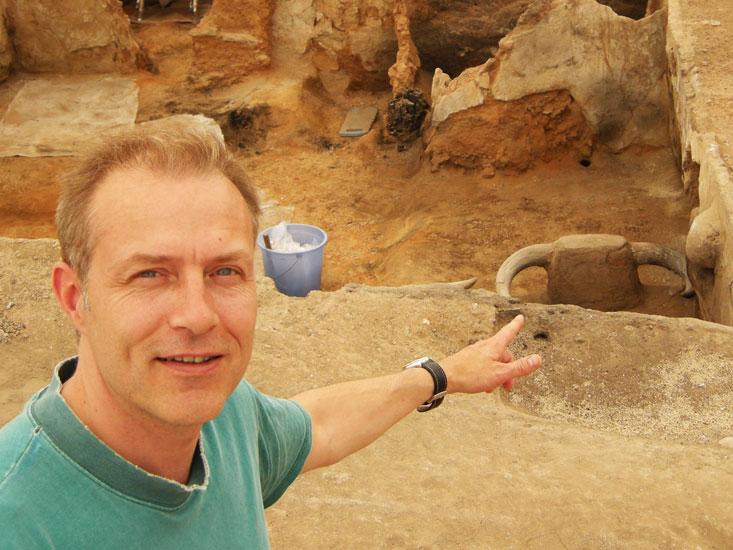

Anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse thinks too much talk about religion is based on loose conjecture and simplistic explanations. Whitehouse directs the Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology at Oxford University. For years he’s been collaborating with scholars around the world to build a massive body of data that grounds the study of religion in science. Whitehouse draws on an array of disciplines—archeology, ethnography, history, evolutionary psychology, cognitive science—to construct a profile of religious practices.

Whitehouse’s fascination with religion goes back to his own groundbreaking field study of traditional beliefs in Papua New Guinea in the 1980s. He developed a theory of religion based on the power of rituals to create social bonds and group identity. He saw that difficult rituals, like traumatic initiation rites, were often unforgettable and had the effect of fusing an individual’s identity with the group. Over the years Whitehouse’s theory of religiosity has sparked considerable debate and spawned several international conferences.

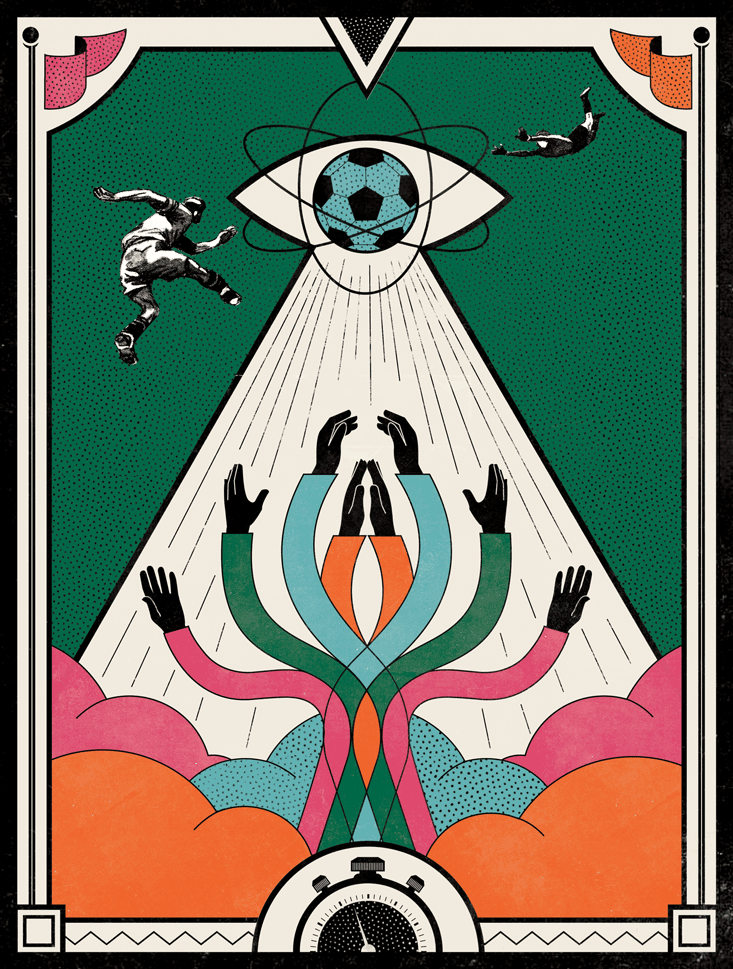

Whitehouse remains a busy man in charge of various research projects. I caught up with him during a brief layover in London between trips to South America and Hong Kong. He’d just returned from Brazil, where he met with two research groups studying how soccer fans bond with each other in that football-mad nation. In our interview, we ranged over a wide range of topics: the social utility of difficult, often painful rituals; the psychological power of “God” in large societies; and why it’s so hard to come up with a good definition of religion.

How far back can we trace religion in human history?

Well, one thing we need to sort out is what we mean by “religion.” People use this as a blanket term for many different things—belief in God or gods, belief in souls and the afterlife, magical spells, rituals, altered states of consciousness. Some of these things are incredibly hard to see in the ancient past, particularly in prehistory.

So what do you look for?

Archaeologists spend a lot of time looking for evidence of ritual activity. Some of the best evidence of belief in the afterlife comes from grave goods like pendants and beaded necklaces found in human burials. Some African sites date back more than a quarter of a million years.

How do you know these burial sites had something to do with the afterlife?

When people leave grave goods, there’s a strong suggestion that they imagine that’s not the end of the person they’re laying to rest. I think some of the paleolithic cave paintings are also suggestive. Lots of materials in those caves suggest that altered states of consciousness were being experienced. These environments have really remarkable acoustics, and you can imagine how lighting could be manipulated to enhance the effects on people.

What are you learning about the origins of religion based on this ancient archeological evidence?

When we can see how frequently certain kinds of rituals were performed, we think it’s possible to estimate—based on animal remains, for example—how often feasting events occurred. Some rituals involved killing large and dangerous animals. It’s been estimated that meat from a wild bull could feed 1,000 people. We can learn from burials, particularly in houses where burials are associated with founding events or closures. We can then estimate the frequency of particular rituals. The frequency of a ritual will be inversely proportional to the level of arousal it induces. Those inducers include sensory pageantry, singing, dancing, music, altered states of consciousness, and painful or traumatic procedures. We find that religions with high-frequency rituals will be more hierarchical than traditions that lack those rituals.

There’s a sacredness to religion that people don’t associate with supporting a football team. But frankly a lot of football fans hold their team pretty sacred.

One common explanation for the origin of religion is that gods and supernatural beings could explain things that didn’t make any sense, whether it was the explosion of thunder or the death of a child. Was that the root of religious belief?

I suppose people do try to fill in the gaps in their knowledge by invoking supernatural explanations. But many other situations prompt supernatural explanations. Perhaps the most common one is thinking there’s a ritual that can help us when we’re doing something with a high risk of failure. Lots of people go to football matches wearing their lucky pants or lucky shirt. And you get players doing all sorts of rituals when there’s a high-risk situation like taking a penalty kick.

So ritualistic activities in a football match are not that different from explicitly religious rituals?

No. In fact, I find it odd that people would even want to think that they’re different. Psychologically, they’re so incredibly similar.

But presumably what sets religion apart is something to do with the transcendent, with another dimension of reality.

It’s true that there’s a certain sacredness to religion that people don’t associate with supporting a football team. But frankly a lot of football fans hold their team and all its emblems pretty sacred. We tend to take a few bits and pieces of the most familiar religions and see them as emblematic of what’s ancient and pan-human. But those things that are ancient and pan-human are actually ubiquitous and not really part of world religions.

Again, it really depends on what we mean by “religion.” I think the best way to answer that question is to try and figure out which cognitive capacities came first. We know that tool-use goes back deep in history. Homo habilis, otherwise known as handyman, is an early species that used tools, so it’s quite possible that he had some notion of creator beings. Language clearly plays an important role in some aspects of religion, like the development of a doctrinal system. But I’m not sure it’s necessary for many of the fundamental beliefs that undergird what we think of as religion.

All religions seem to have creation stories. Don’t you need language to formulate this kind of mythic imagination?

When you look at the myths of many cultural traditions, they seem to have a kind of dreamlike quality. Often they’re actually inspired by dreams. Dreaming seems to be a widespread feature of the mammalian brain, so while it’s true that sharing dreams depends on language, having dreams doesn’t require language. I’m guessing the mythic imagination wouldn’t depend on having a language.

At some point in human history many societies switched from animistic forms of religion to institutionalized systems that are closer to today’s religions. How do you explain this transition?

The really critical transition is one that occurs in the gradual switch from a foraging, hunting-and-gathering lifestyle to settled agriculture, where you’re domesticating animals and cultivating crops. What happens is a major change in group size and structure. I think religion is really a core feature in that change. What we see in the archeological record is increasing frequency of collective rituals. This changes things psychologically and leads to more doctrinal kinds of religious systems, which are more recognizable when we look at world religions today.

If I’d grown up in different parts of the world—for example, in Papua New Guinea, where I did my fieldwork—I’m quite sure I would be religious.

Why did that transformation occur in agricultural societies?

The cooperation required in large settled communities is different from what you need in a small group based on face-to-face ties between people. When you’re facing high-risk encounters with other groups or dangerous animals, what you want in a small group is people so strongly bonded that they really stick together. The rituals that seem best-designed to do that are emotionally intense but not performed all that frequently. But when the group is too large for you to know everyone personally, you need to bind people together through group categories, like an ethnic group or a religious organization. The high frequency rituals in larger religions make you lose sight of your personal self.

I suppose an example of social bonding would be the Muslim practice of praying five times a day.

Or in Christianity, it’s going to church regularly to attend services. All really large-scale religions have rituals that people perform daily or at least once a week. We think this is one of the key differences between simply identifying with a group and being fused with a group. When you’re fused with a group, a person’s social identity really taps into personal identity as well. And identity fusion has a number of behavioral outcomes. Perhaps most importantly, fused individuals demonstrate a significant willingness to sacrifice themselves for their groups.

What about the other kind of ritual where you have very intense experiences?

A lot of small groups are bound together through painful or frightening initiation rituals, particularly in groups that face high levels of threat from people outside their group. You need to stand together firmly to resist. Where I worked in New Guinea, a lot of the small tribal groups had initiation rites for boys and young men. They emerged as tightly bonded military units capable of carrying out raids against neighboring villages. We see the same sort of thing in modern armies. The elite forces have dysphoric training programs and informal initiation rites that bind the group together.

A secular example of these initiations would be the hazing rituals in a college fraternity.

That’s right. We’re developing a survey to see whether the intensity of hazing rituals in fraternities and sororities correlates with group fusion. We’ve also been researching military groups and football fans. What we’re finding is that football fans that suffer more are also more bonded. Going through bad experiences together is actually a more powerful bonding agent than simply having a good time.

Doesn’t a well-trained army have to break down a soldier’s individuality so that he’s committed to helping his comrades?

I think that’s right. Painful or bad experiences are remembered better and become part of our sense of who we are, what makes me, me and you, you. Sharing those powerful experiences breaks down the boundary between self and other and creates the psychological state that we call fusion. One of the interesting correlates of being fused with a group is willingness to fight and die for it. So people willing to make huge sacrifices to groups are typically fused with them.

What brought you to Papua New Guinea?

I didn’t intend to study religion. I’d gone out there to study economic anthropology, but these people had other ideas. They were all members of a religious movement calling itself the Kivung, which had a huge number of beliefs and practices geared toward bringing the ancestors back from the dead. This was what people really wanted me to understand.

Can you describe some of these rituals to bring back the dead?

There were two aspects to the movement and this is really what has driven so much of my later research. There was a large tradition uniting hundreds of villages and thousands of followers across quite a wide region. It involved very high frequency rituals, most of which were focused on laying out offerings to the ancestors in specially constructed temples. Operating on a very large scale, it was quite hierarchical and very well organized. But there were also small groups that sporadically broke away and performed much more emotionally intense rituals that seemed to have a very powerful bonding effect, even though they never succeeded in bringing the ancestors back from the dead.

What were these intense rituals in smaller groups?

In the village where I lived, they performed special rituals where they discarded their clothes and went around naked, which had quite an emotional impact, particularly on women who were exposing their bodies to the predatory gaze of men. They destroyed all their animals and had huge feasts, performing a mass marriage and lots of rituals that were intended to herald the return of the ancestors. They performed vigils under quite difficult conditions where people were forbidden to leave and were forced to endure unpleasant conditions.

Did they ever explain why they thought these rituals would bring back their ancestors?

They had a complex doctrinal system that explained the history of the world and the relationships between their groups and white folks. It’s a long and complicated story. As in any religion, I’m not sure that everyone bought into every detail of the doctrine. The most compelling aspect of this belief system is that they would be released from a history of exploitation through a brotherhood with invading colonial powers.

They talked about a period when ethnically European businessmen and technologists would appear in the jungle and create, magically overnight, huge high-rise buildings and cities, and they would have a Western lifestyle as a result. But those European people would actually be ancestors of the group who’d just come back from the dead but with the appearance of white skin and European-type hair.

So they thought bringing back their ancestors would give them an opulent lifestyle?

I don’t think it was just about being wealthy in a crass materialistic sense. It was about release from all the sufferings of the hard life that they lived in the forest, where horrible sores, tropical ulcers, malaria, and all kinds of diseases and injuries—including premature death of loved ones—are a common part of everyday life. They were really dreaming of a time when all of that suffering would be eliminated.

While it appears that people are dying for religious causes, I actually think it would be truer to say they die for each other.

You’re suggesting you don’t have to reduce religious experience to belief systems. It’s the experience itself that sweeps you along and binds you to other people.

It’s about both belief and experience. I do think we can kind of separate the two. Imagine having a brain that’s naturally predisposed to believe some things more readily than others, and then over generations, cultural systems develop in ways that essentially play into those predispositions. The point is that our experiences are made meaningful by our implicit beliefs and the two basically work together.

If there’s such a thing as a “big bang” of religion, it would seem to be the Axial Age, the period from 800 to 200 B.C. when various sages—Plato, Confucius, Jeremiah, the Buddha—all emerged. These people not only shaped some of today’s major religions; they helped create the world we still live in. Do you see this as a watershed in the history of religion?

I think there were some major social and cultural changes during that period, but were they distinctive enough to think of that age as axial or pivotal? It’s hard to answer that without looking like we’re cherry-picking the evidence to fit the argument that we prefer. To adjudicate on this question we need a large database in archeological, ethnographic, and historical materials. We’d have a huge storehouse of information where we can look for correlations over long time periods going back as far as history will allow. We’ll be able to look more objectively and systematically at the patterns we’re interested in.

Do you think science can fully explain religion?

I don’t know about fully explain. I’d like to think that science will one day be able to explain why we’re inclined to adopt these different things that we lump together as religion, but I don’t think explaining religion is the same as explaining it away. I don’t think science will ever be able to tell us whether or not there’s a god. That will always be a matter of faith. I’m in favor of a humble approach, but I do think that humility should cut both ways. Religious people should be open to the possibility that some of the things they find most mysterious about the meaning of life or the cosmos might actually turn out to be explainable. Of course, science has been pretty successful at turning certain mysteries into soluble problems. But at the same time I think much of human life takes us beyond the scope of scientific explanation and that’s true of religion, too.

Psychologically, why is God such a powerful idea?

It may be a product of cultural evolution and the shift to much larger and more complex societies. When you use the singular “God,” you’re talking about some kind of high god, which probably means a god that’s omniscient and cares about the morality of our behavior and punishes us when we behave badly. That’s a relatively recent cultural innovation that may have been an adaptation to living in very large societies.

So once society becomes very big, you can no longer see what everyone is doing and you can’t police moral behavior. But if this high god is watching you, there’s still an imperative to be good?

It’s become known as the “supernatural watcher” hypothesis. The idea of an eye in the sky is quite compelling. But I think we need more empirical research to be really confident that it’s true.

I’m curious, are you religious yourself?

Well, I’ve got the full repertoire of religious intuitions like everyone else. I don’t personally subscribe to beliefs in the supernatural, and since I’m not a member of an organized religion, I suppose you could say that I’m not religious. But like I said earlier, it really depends on what you count as religious. I actually think on one level we’re all religious, even atheists. People can train themselves to dismiss religious intuitions, but I don’t think they can eradicate them.

What kinds of intuitions are you talking about?

The intuition that when people die they’re still around in some sense. I think we have that intuition whether we declare ourselves to be religious or not. And the sense of being watched when you’re doing something you should feel guilty about. When you see the amazing features of the natural environment—like rivers, marine life, trees in the forest—it’s hard not to believe that some creator put them there. Our brains are set up to put a designer in charge of that extraordinary complexity of design. I think we have the intuition that there are supernatural agents around, that they created the world, that we live on after we die. The question is whether we buy into a cultural tradition that builds on those ideas and turns them into something more formalized and doctrinally coherent. I don’t myself, but I think a lot of people around the world don’t have much choice. If I’d grown up in different parts of the world—for example, in Papua New Guinea, where I did my fieldwork—I’m quite sure I would be religious. It’s been interesting to see the decline of organized religion in certain countries, which are usually affluent, safe, and secure. As life gets easier, you could say people get more selfish and less attached to group values.

But if the core impulse of religion is to help us find meaning and purpose in our lives, shouldn’t that also apply to affluent societies?

That’s true, but the question is how we go about looking for meaning in the world. I personally don’t agree with the idea that the main explanation for religion is that we’re on a quest for meaning. I think we need to look at what participation in a particular cultural tradition—religious or otherwise—does for the individual and the community. There are lots of different components to religion. But if we’re just thinking about the ones that are universal, that seem to be part of our evolved psychology, I don’t think innate curiosity and desire to puzzle together the meaning of life explains religion.

And so what does, in summary, explain religion?

Well, it’s not a monolithic entity for which we could offer an overall explanation. If we define what we’re really interested in—supernatural agents, rituals, afterlife beliefs, creation stories—then we’d find they result from quite different mechanisms and have different evolutionary histories. There just can’t be a magic bullet explanation of “religion” as if it’s one single thing.

What do you think of the New Atheist critique of religion—not only that belief in God is intellectually bankrupt, but also that religion is dangerous?

It’s a difficult question. The New Atheists tend to take a rather shallow view of religion as simply a set of propositions about the world. To understand the power of religion, I think we need to understand what it does for individuals and communities. When the New Atheists consider those sorts of questions, they seem to take a very jaundiced view. They tend to insist that religion makes us do bad or foolish things. And I think claims of that kind are often heavy on rhetoric but light on systematic and balanced observation.

But the New Atheists point out that many people who’ve committed violence, even terrorism, have done so in the name of certain religious beliefs.

It’s possible that’s the case. We’re currently engaged in a careful study of the phenomenon of self-sacrifice in these sorts of conditions. For example, we went into the revolution in Libya in 2011. One of my students, Brian McQuinn, was holed up in Misrata throughout the siege of that city, studying the groups committed to risking their lives—and in many cases laying down their lives—for the cause. Virtually all of them were Muslims. There were individuals whose job was to chant “Allah is great” as they were engaged in house-to-house combat. The whole system of beliefs and activities was suffused with religion. But while it appears that people are dying for religious causes, I actually think it would be truer to say they die for each other. I think first and foremost we bond with a small group based on our personal ties with individual members. And when we’re prepared to put our lives on the line, it’s for those people rather than for something as abstract as a religious idea.

Steve Paulson is the executive producer of Wisconsin Public Radio’s nationally syndicated show, “To the Best of Our Knowledge.” He’s the author of Atoms and Eden: Conversations on Religion and Science.