Have you ever had the experience of being so absorbed by a painting or a piece of music,” writes Anjan Chatterjee in his 2013 book The Aesthetic Brain, “that you lose all sense of space and time? These magical moments … are ironically deeply subjective. The problem, of course, is that science demands some objectivity.”

Such is the tension that runs through the burgeoning field of neuroaesthetics, of which Chatterjee is a champion. As a neuroscientist grounded in evolutionary psychology, but also as a philosopher and an amateur photographer, he is able to weave together the threads of both aesthetics and neuroscience, while understanding the limits of each.

Chatterjee’s interest in aesthetic experience began in his childhood in India, where he mastered one of the oldest forms of human expression at a young age. He started to draw with a concentrated passion when he was 6 years old. In 1980, Chatterjee graduated from Haverford College with a major in philosophy. It was while at medical school that he discovered his love for reading neuroscience. “Not to pass tests,” he said, “but because I actually wanted to know the information. That was the first clue that I would want to train in the clinical neurosciences.”

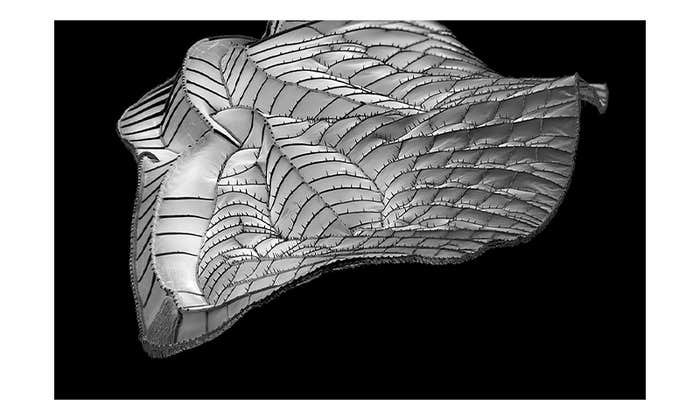

His instrument of choice evolved from a pencil to a camera in 1989, when he finished his neurology residency and, for the first time in eight years, found time to again respond creatively to his observations and insights. Now, he says, “I photograph many things—street, landscapes, abstracts. I believe almost anything can be photographed—it is the aesthetic attitude of the photographer rather than the object that drives the image.” A gallery of his images can be seen here.

In The Aesthetic Brain, Chatterjee tells us that our ability to have aesthetic experiences has its origins deep in our brains, in the orbitofrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens, and is aided by neurotransmitters such as dopamine, opiates, and cannabibens, which control emotional responses. These responses developed, Chatterjee says, because they were useful for survival. But what happens to our aesthetic sense when the demands of survival are removed?

We caught up with Chatterjee last November at his office in the University of Pennsylvania’s Pennsylvania Hospital, where he is the new head of Neurology.

Gayil Nalls, Ph.D., is an interdisciplinary artist, philosopher, and theorist. Her work investigates personal and collective sensory experiences, memory, and identity.

View Video

What makes an experience aesthetic?

You’ve suggested that aesthetics stems from prioritizing liking over wanting. How?

Can science quantify a transcendent experience?

Does our knowledge of brain structure help us understand aesthetics?

Do we react differently to regular objects when we’re told they’re art?

How does birdsong help us understand our own art?

What are the various stages of the creative act?

How can we be more creative?

What would you be if you weren’t a scientist?

Interview Transcript

What makes an experience aesthetic?

There are certain configurations of sensations, of the way objects are configured in the world, that give rise to an experience that seems to be qualitatively different than just straight perception, or straight objects on which we act, that have been called aesthetic experiences. Many aesthetic experiences are thought to be pleasurable: If things are beautiful, we like them, we derive pleasure from them. But there are a lot of things that we get pleasure from—such as a nice meal, being in the presence of an attractive partner; it’s not clear that those are aesthetic experiences although they are pleasurable experiences.

So one definitional approach is to suggest that aesthetic experiences are a class of pleasurable experiences, or emotional experiences, that are not accompanied by an appetitive impulse or a utilitarian impulse. And so the example would be that you could look at a beautiful painting and have a number of experiences simultaneously. You could think, “Oh that looks great, that would look great in my living room or in my office.” “It might be a great investment.” “It would impress my friends.” And those are all, you know, possibly rewarding experiences but we typically don’t think of them as “aesthetic.”

The general idea is that aesthetic experiences are self-contained. We sometimes talk about art for art’s sake; but they’re self-contained and don’t extend beyond the immersive experience of engaging with an object. And I think most people have some sense of what that is. It doesn’t have to be an art object, it can be a natural object. It can be a beautiful garden that you’re completely immersed in—its beauty. And that, we think, is probably at least one definition of what an aesthetic experience is.

You’ve suggested that aesthetics stems from prioritizing liking over wanting. How?

When people talk about rewarding experiences in the brain, these tend to be carried out within deep structures of the brain—so parts of our emotional system, parts of the brain that are called the ventral striatum, or the frontal cortex, and the amygdala, and parts of the insula. So there’s this kind of network of brain structures within the brain that seem to be important for how we evaluate things and our reward systems.

Within that, there is a division of two systems that a neuroscientist at [the University of] Michigan named Kent Berridge has referred to as the “wanting and the liking” system. And the general idea there is that we typically like things we want and we want things we like, so these two systems operate in concert, as they should. But they have slightly different neurochemical bases and their anatomy is somewhat different. So one thing tends to be driven by dopamine. As an important neurochemical for our reward system, it’s important for learning, it’s important for movement—so people, for example, with Parkinson’s disease have a deficient state in dopamine and so their movements get constricted; they’re very slow. But [dopamine] is also important for learning and it’s important for our drive to get to things that we desire. Distinct from that is a separate system that is what Berridge calls the “liking” system and this is about the system that is purely the hedonic experience of something and that is mediated by cannabinoid and opioid receptors in the brain. So when people ingest cannabinoids or opioids, the kind of high you get from that is an exaggerated version of how these systems work in the normal brain.

So again, both systems tend to work together in most of our experiences—we want what we like and we like what we want—however, they can get dissociated. One example of a dissociation where you can have wanting without as much liking are in addictive states. So people as they progress and become quite addicted, crave their fix, so this desire to get their fix is extremely exaggerated. But it’s not clear that they enjoy the experience in the same way that they did. So that seems to be a dissociation that moves in one direction.

What I speculate in my book is that it’s the opposite weightings where you have liking—where the wanting is not as prominent in the experience—is what we would characterize as an aesthetic experience.

Can science quantify a transcendent experience?

There is a group at NYU that has tried to do this and has done it in a way that suggests that there might be some traction on this. Specifically what they did is an experiment where people are in a scanner while they’re having their brains imaged [as] they’re looking at a variety of paintings. [They] were asked to rate these paintings on a scale going from one to four or five for how much they liked it. But part of the point of the study was, at the most extreme ranges of whether they liked it, something qualitatively different was going on in their brains. So even though the rating was a linear scale, at the highest standard, there was something qualitatively different happening in their brain and there are a set of brain structures that tend to be engaged in those experiences that in the literature has been now referred to as the “default mode network.”

So the default mode network is a series of parts of the brain that are more engaged when people—the syntax of this isn’t going to be so clear—when people are more engaged by not being engaged by external things in the world. So if you are engaged in a task, or some perception, or an action, the default mode network actually decreases in activation. Most people think the default mode network has to do with turning inward—it’s related to the kind of mind-wandering experiences people have—sort of self-referential, but not in a very constrained fashion. And so what these people, what this group at NYU speculates and suggests, [is] that maybe one interpretation of this is in those transcendent experiences with art at the extremes. You know, there is a kind of gradual incremental pleasure in art but at some point it changes qualitatively and when that happens, this external stimulus actually serves as a trigger for people to turn inward and have this kind of state that you typically see when people are not engaged with something outside the world.

There’s something else that is referred to as the salience network, which is when things are salient in the environment and as best we can tell, the salience network and the default mode network work in a reciprocal fashion. So when the salient network is more active, the default mode network is less active and vice versa.

While there’s still a lot of work that has to be done with this, the general idea that seems to be emerging is that there are conditions where you need to be quite aware of your surroundings and vigilant and there are conditions where you can shut that off and turn inward. I think that’s the kind of system we’re talking about and what’s interesting about this finding is it suggests that artwork—when people have this extreme experience, transcendent experience—while it’s being triggered by something externally, it’s driving our brain into this inward system.

Does our knowledge of brain structure help us understand aesthetics?

I think what neuroaesthetics does is it gives greater texture to our understanding of what aesthetic experiences are. One of the things that I and several other people in this domain have talked about is that what we refer to as the aesthetic triad, which is that there are sensory motor circuitry in the brain, there are emotional and reward circuitry in the brain, and there are semantic conceptual circuitry in the brain and that out of those three things, is the possibility of an aesthetic experience. And so the reason for bringing that up is one criticism that scientific aesthetics has often had is that much of what we typically study is thinking of aesthetics in the way people did in the 18th century and we don’t really deal with contemporary art. You know so if you go down to galleries in the SoHo or you know any major city, it’s not clear for example that beauty is a big feature of what is going on in contemporary art right now. And so the criticism has been that people who do scientific aesthetics are asking questions that aren’t making contact with the conversations that are going on in the art world right now.

So it brings up this question, particularly around conceptual artwork and where semantics plays into this and I think what, talking about this aesthetic triad, the advantage there was, it allows you to put this in a scientific framework where you can say that for conceptual art, the sensory motor features are not as salient in that aesthetic experience. But what you have is a link between this, the conceptual structure which is the knowledge around this and the emotional reaction, right, so that’s the principle axis on which this aesthetic experience is based.

Another example in which you remove the conceptual piece, at least for me, would be if you look at Australian Aboriginal art which I find quite pleasing, but at the same time I don’t have the conceptual structure behind it, what the cultural background of this, what it means within the context of its being made. But without having that conceptual information I can still have an aesthetic experience with it.

So, I think the way you can use neuroaesthetics is to provide this kind of framework and say depending on the kind of art that you’re dealing with, it will engage different parts of the brain, but it gives us a framework with which to try to understand what’s happening in the brain.

Do we react differently to regular objects when we’re told they’re art?

So if you have urinal on a pedestal or if you have, you know, Brillo boxes that are indistinguishable from what you might find in a grocery store. If we communally decide this is art, when given the right context, then we say this is art. And that makes it hard, I think, to find necessary and sufficient conditions for what art is, but it does mean that the nature of art changes over time and our response to art changes over time. A clear example of that are the Impressionist painters who, when they first came on the scene, were pretty much denigrated at large. And now in most surveys if you ask people, particularly in western developed countries, what their favorite art is, people will typically talk about Impressionist works. Our brains haven’t really changed in 150 years, but there is something about the cultural context in which we approach these that makes people not only accept that they’re artwork, but actually like them, and say they like them, more. This idea of knowledge and how this plays into this, there have been some experiments that have looked at this in a very, in a smaller way, but I think does have implications. There is one experiment that was done by a Danish group, again an imaging experiment, where people were shown abstract images. And in one condition they’re told that these were generated by a computer; some random algorithm is generating these images. In another condition they’re told that these exact, identical objects are hanging in a gallery. So what they’re seeing, so in this case their perception of the object is exactly the same, it’s just given a different context. Behaviorally what they find is people will say that if they’re hanging in a gallery that they like it better. But it’s not just a verbal account. When they look at their brain activity, parts of the orbitofrontal context, which is one of these areas that where we think, that encodes value in people’s pleasures, they actually have greater activity in this area if they think it’s hanging in a gallery, suggesting that these contextual effects, these educational effects, actually influence our pleasures more directly. And it’s not just that they’re saying they like it because they think if it’s in a gallery they have to, that’s what’s expected by the experimenters.

How does birdsong help us understand our own art?

The argument for this comes from a particular bird that is endemic in Southeast Asia called the white-rumped munia. About 200 to 250 years ago, a Japanese collector started collecting this bird and breeding it in Japan specifically for its plumage, okay? So, what you have are these wild type birds, feral birds, that use their songs for mating purposes, and like birdsongs are often used as an example of a kind of proto art that might give us some insight into our behaviors. The question is, what happens to their songs when the song is no longer important for reproductive success? Because the breeders now have them in this artificial environment, they don’t care about their song. They’re picking them for what their feathers look like and breeding accordingly. So now the song has no advantage over, you know, minor variations in the song, and what they find over 250 years is that the song of this bird which evolves into what is referred to as the Bengalese finch, the song of this bird changes, and changes in quite interesting ways, which is that it is more variable, it is more susceptible or influenced by its environment, that these birds are able to acquire other songs more easily, and the structure of the songs are more complex than what you see in the white-rumped munia. When people have looked at the neural basis of these respective songs, in the white-rumped munia, most of the neural organization of the song production happens subcortically in these parts of the brain that would be analogous to the basal ganglia of the human. So it seems to be habitual kinds of song making, not a lot of variation.

What you see in the Bengalese finch is that there is all this cortical control over that same basic structure, and that you can then lesion parts of the cortex and it reduces back to the original sort of more stereotypic song. So one implication of this is that when you remove adaptive constraints, when you have a relaxation of adaptive constraints, that several things can happen to what starts out as a stereotypic behavior, which is it can just wither and degenerate and die, which happens a lot, or it can actually become more variable and because the environmental constraints are no longer selecting for certain behaviors, the behavior itself becomes more variable. So my speculation in the book is that the kinds of adaptive functions that art typically had, or at least people have argued, which is immune, so social cohesion for example is a good example, that in contemporary society those factors that have had selective advantages no longer apply. As a result, it allows art to become more variable and to drift more, that this kind of drift in what constitutes art blossoms precisely because you don’t have the same selective pressures that you might have had in an earlier era. I think that’s partly why we have so much variability in art right now, in a way that sometimes people who are not engaged in contemporary discussions of art are often puzzled by, you know, “why is this thing art?”

What are the various stages of the creative act?

So, generally people think that there are four stages involved in creativity. The first stage people often refer to as a preparatory stage, which is that there are certain sets of tools and basic elements that you have to acquire, basic skills you have to acquire on which you can then be creative. Without that there is nothing to be creative on. After that there is this period that is sometimes called the incubation period where you’re trying to solve a problem but it’s not happening. You might try analytic approaches but they’re not quite working and so but there’s this sense that something below the surface of consciousness is happening. It’s not just a dead state right but it’s not progressing incrementally in the way that an analytic solution to a problem might be, and then there are these “Aha” moments right which, where something is illuminated, something reconfigures and all of a sudden you see a solution that makes you change how you’re thinking about it and then the final is the elaboration which is once you’ve had that you actually have to put it out there, right it’s not sufficient just to have that in your own head, that you have to put it out there. So those are the four stages that people typically think about and, you know, there are arguments of whether they really happen sequentially or do people bounce back and forth, the dynamics of that are unclear, but it does look like that specifically in that period, the incubation to the illumination piece, right, that’s what most people think as the sort of quintessential piece of creativity, right, there’s something happening, something magical happens where things get reconfigured. In terms of the neural understanding of that it does look like there are parts within the right hemisphere parts of the temporal cortex that seem to be especially active during those periods and there is electrical activity, people have done EEG studies to show that right before that moment in the occipital cortex you actually have an increase of alpha rhythms which is an electrical marker for the idea that processing there is being inhibited and so there is this idea that right at the point where you’re about to get to a solution, it’s almost as though people naturally, for example, will close their eyes that that’s happening in the brain, that sensory information is being suppressed right at that point where the solution seems to emerge and to me that’s a pretty fascinating sort of empirical observation where people have tried to capture what feels like a magical thing, that it’s very mysterious how this actually happens.

How can we be more creative?

There’s a broader cultural way in which this question concerns me. It concerns me in the sense that we may be setting up people to be less creative over time and what I mean by that is that you can take analytic approaches to problems right, where you just sequentially, you pound away at it, pound away at it, right, and that’s a very different way of approaching things than what’s involved in what we think of as creative, which is really reconfiguring the problem and seeing it in a different way. I think that for the second, for what we would probably think is more paradigmatic of creative approaches, a critical piece there is that downtime, right, the incubation to illumination so you have to do the work to get your skills up but you need the downtime, right, where you’re thinking broadly, you’re not being so analytic, you’re even letting your mind wander. People often have the experience that in conditions of low arousal—so people when they’re falling asleep or when they’re waking up; for me it’s often when I’m in the shower in the morning before I’ve had my coffee—it’s these kind of hazy states where those illumination moments happen, right, following the incubation.

And there is something about lower levels of arousal, which is the opposite of what you have when you’re being very analytic, right. You have to be on target, you have to be very analytic about things. It’s the opposite of that that allows those moments of insight. And so one concern I have is that as a culture we are not letting our children have that kind of unstructured downtime, right, that kids … I mean I know my nephews who are both in college now, when they were in middle school, I mean they had schedules that were more complicated than mine. Every hour seemed like it was scheduled, whether it was lessons or practices and, you know, in many parts of our culture I think this idea that kids are just out not doing anything … but they are doing stuff, but not doing anything that you can put on a CV or, you know, [that] can help you get into the right schools. I think we’re not giving people that downtime and I’m using kids as an example but I think this is true for many of our lives, which is that we’re so driven by having a kind of productivity that doesn’t allow as much downtime as I think that in the long run is important for those creative insights.

What would you be if you weren’t a scientist?

If I wasn’t a neuroscientist there are probably several things … My undergraduate degree was in philosophy and so a big choice for me was whether to go into philosophy grad school and be a professional philosopher versus going to medical school, which is what I did. So that would be one possible path but that’s still in the kind of academic.

There was probably a period of—around 12 years ago—where I wasn’t sure if I was going to continue to be an academic of the form that I am right now and at the time, one thing I considered was dropping it all and just being a straight photographer. So that’s one possibility. And the final is actually, just in writing this book, The Aesthetic Brain, which is the first time I’ve done any extended writing which was not specifically for a scientific audience and not in the context of peer reviewed, you know, where you have to be very close to the data—I actually found that I liked that kind of writing quite a bit and so I could imagine doing, I could imagine doing popular science writing as an alternate career.