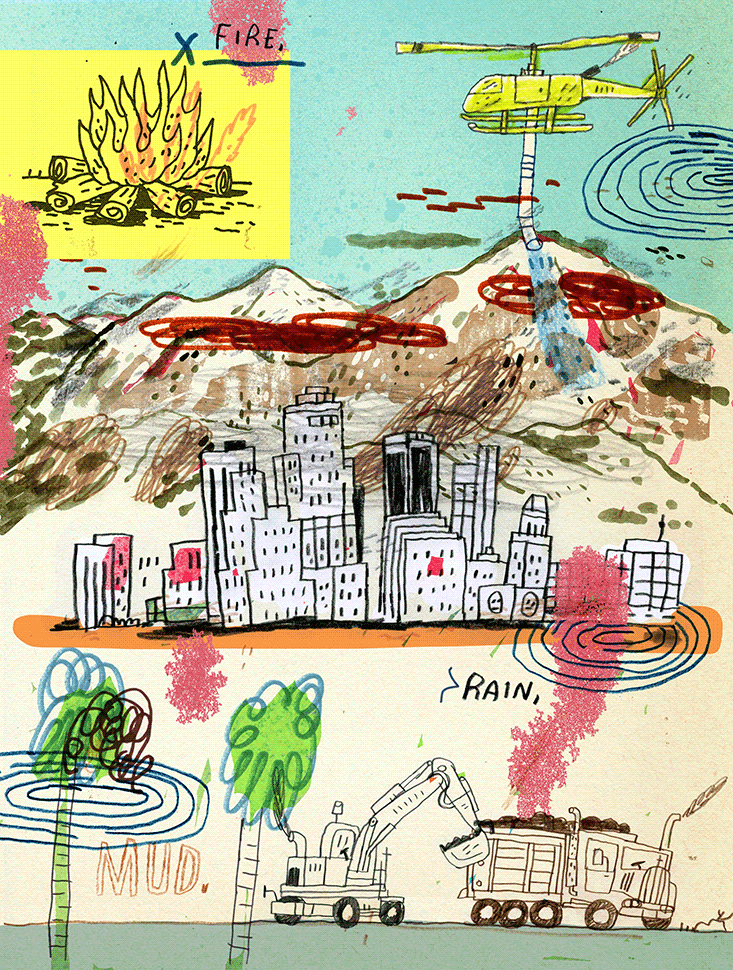

The San Gabriel Mountains are waging war on Los Angeles and Ed Heinlein’s chainsaw is screaming in the late afternoon sun. It’s January 2015 and Heinlein, who has a friendly paunch and paws sheathed in mud-stained work gloves, is carving up avocado trees. They were drowned the previous year when a series of mud freight trains roared out of the hills above his house. “Welcome to mud central,” says Heinlein, “The assistant fire chief tells me it’s the most dangerous property in L.A.”

Heinlein is a retired elementary school teacher, current Christian minister, and has a preacher’s tendency to speak in terms of fire and brimstone. He lives in Azusa, a scenic nook in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, which rise 10,000 feet above the city of Los Angeles. Aware that the mountain range’s mud war is far from over, Heinlein has spent more than $100,000 to protect his property behind a trio of steel and concrete walls. Immediately surrounding his home is a final barrier, consisting of about 400 sandbags, 60 sheets of plywood and heavy plastic sheeting. It is a mighty fortification, so complete that Heinlein and his family cannot even exit their backdoor.

The mountains have been hammering Los Angeles for as long as Heinlein, 66, can remember. In 1969, tremendous rains caused a 20-foot wave of muddy debris to race down the mountains, burying homes and streets, and together with related flooding and landslides, killing more than 100 people in the foothills. Still, the developers keep building. As the evening sky goes purple then black and stars come out, Heinlein silences his chainsaw and points across the valley to a tract of twinkling multi-million-dollar homes. “When the big one comes, there’s nothing my walls can do, nothing anyone can do,” he says. “People in that new development are going to be trapped, and they’ll be flying them out in helicopters.”

Los Angeles was not built upon Hollywood or citrus groves or oil. It was built upon mud and sand and gravel.

A quarter of a century ago, master scribe John McPhee wrote about the San Gabriel Mountains’ profoundly destructive rivers of mud, called debris flows, in a pair of New Yorker articles titled “Los Angeles Against the Mountains.” These large watery pulses of mud and rock are triggered by rain and often fire and charge down steep stream and gully channels. Upon encountering flatter terrain, such as the graded lot of Heinlein’s house, they fan out to form thick muddy deposits. One of the most devastating debris flows occurred on New Year’s Day, 1934. Following a season of fires, rivers of debris poured down the mountains into the city, killing dozens of people. “Model A’s were so deeply buried that their square roofs stuck out of the mud like rafts,” McPhee wrote.

The Oz-like geologic magician running the show is the San Andreas Fault. It cuts across California from the Mexican border to Cape Mendocino and separates the North American plate, which is moving southeast, from the Pacific plate, which is moving northwest. The San Gabriel Mountains lie along a 150 mile-long kink, where the fault jogs west, and where the Pacific Plate is pushing smack into the North American Plate—hence the mountain range. Geologists estimate the San Gabriels are rising at a rate of 1 millimeter a year. Although fingernails grow 36 times as quick, for a mountain range that is pretty fast.

The San Gabriels are also crumbling fast. Regular earthquake motion along the San Andreas and adjacent faults has riddled the San Gabriels with cracks, weakening the rock. Areas of bedrock beneath the mountains are 1 billion years old, and worn down, adding to the rock’s tendency to crumble. And while glaciers during the last ice age smoothed and sculpted northern California’s mountains, evident in Yosemite’s dramatic rock formations, the San Gabriels were never glaciated and are still carpeted with loose rock. During rainstorms that follow fires, this soil is released in the form of debris flows. Los Angeles, it turns out, was built not upon Hollywood or citrus groves or oil. It was built upon mud and sand and gravel, roughly 1 to 2 million years of debris flows layered upon one another to form a gigantic apron of sediment that rings the mountains and underlies the city. The problem is the mountains are still falling, and the city is still in the way.

The great debris flow of 1934 taught city planners a valuable lesson. In Haines Canyon, wrote McPhee, a gravel pit fortuitously swallowed one flow’s mud, saving the village of Tujunga, which lay downstream. Eureka! “With enough money—enough steam shovels, enough dump trucks, enough basins cupped beneath the falling hills,” said McPhee. “Los Angeles could defy the mountains.”

Man, this is a clear day,” whistles Steve Sheridan. “You don’t get many of these.”

It’s a crisp blue Monday and we are in the foothills above Azusa, watching the sun rise over the city. Sheridan, a short stocky Boston native, with the accent to prove it, is an engineer with Flood Maintenance. This relatively unknown division within the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works has a tremendous task: to hold back the mountains. After fires have loosened the soil and rain has brought it down the hillsides, Flood Maintenance and its debris basins are the last bastion of defense.

Sheridan gestures to the vast metropolis below, a seemingly endless sprawl of homes and buildings, what he likes to call the flatlands. “None of this development down there would be possible without structures like these in the hills,” he says, indicating a modest-sized concrete dam, Beatty Debris Basin, built by the city in 1970. “And a lot of the residents down there have no idea these things even exist.”

Beatty Debris Basin is shaped like a heart and lies at the foot of steep brown hills. For much of the year there is nothing behind the dam, but when debris flows empty out of the hills the basin can fill to the brim with mud in just 30 minutes, as happened at a nearby debris basin during the same late February storm that swamped Heinlein’s home. A video of that event shot by a local couple shows a churning brown sea. “Oh-My-Gosh!” cries the wife. “This is just not good! Oh-My-Gosh!” But Sheridan, who chuckles when he tells the story, says she shouldn’t have been so surprised, the debris basin was doing exactly what it was designed to do.

That is, mud flows out of the hills via streams and gullies then is stopped by concrete or earthen dams. Material pools up in the basin, and a spillway whose entrance is partially barricaded by wood planks allows water to drain, ideally keeping out rocks and trees—20 foot-long trunks are not uncommon. Water also drains through thin slots in a concrete vertical tower, located in the middle of the basin. A similar structure, called an incline tower, lies flat against the bottom edge of the basin. These structures are critical, as the quicker a basin can be drained, the quicker the soil and debris can be organized by Sheridan’s men and hauled away. And in winter, when storms can stack up against the coast, there is very real pressure to get the mud out quickly.

The job may be urgent, but the tools are simple, even antiquated. After big events, Sheridan’s men “clear the weedies,” which involves rowing an aluminum boat to the vertical tower and using potato picks to untangle the threads of vegetation that clog the tower’s slots. An excavator builds a “finger levee,” a raised road of mud that allows the machine to drive beside the tower and begin scooping material, allowing more water to drain. Water drained through the vertical and incline towers joins water drained through the spillway and enters a system of concrete channels— Los Angeles County has 3,300 miles of these channels—that cut across the county to the sea.

I can’t help but reflect that most L.A. County residents are kept safe behind barriers they don’t even know exist.

H2O is precious in L.A., and in 30 spots across the county water is diverted out of the concrete channels—the role of a division within Public Works called Water Resources—and into a network of flat barren fields that resemble rice paddies. These “spreading grounds” allow water to percolate down through layers of rock and sediment underlying the city and replenish the highly utilized water table. Looking to either side of Beatty Debris Basin one can see why these water conservation structures are so essential: people. A housing development flanks one side of the basin and on the other side a new one is going up, freshly laid Spanish roofing tiles glinting in the sun.

It wasn’t too far from Beatty where the fire that set the stage for the debris flows that hit Heinlein’s home began. On Jan. 16, 2014 three men camped illegally in the foothills, woke up cold and built a campfire. The blaze swiftly jumped its rock ring and sprinted west along the hilltops, torching trees and brush along the Colby Truck Trail. (The incident is now known as the Colby Fire.) “It looked like hellfire in the sky,” says Heinlein, who was watching from his deck. “Hot embers started raining down, and with God as my witness a Manzanita tree exploded like a drum of fuel and there was a 30-foot ring of fire. Another eight or 10 manzanitas exploded and the whole mountain was alive with fire.”

More than 100 firefighters from four counties battled the blaze. Six weeks later came the rain. Mud and rock began flowing down gullies in the scorched hills above Heinlein’s home, damming up behind a steel fence and swamping his avocado trees. Then in March that year a thunderstorm in the foothills unleashed more mud from the mountains, bursting through Heinlein’s protective fence, burying a basketball court halfway up to the hoop and enveloping his house in a sea of mud 4 feet high.

Errant tongues of mud like the one that lashed Heinlein’s home are an aberration. Approximately 200,000 cubic yards of San Gabriel mud are trapped behind L.A. County debris basins each year. In years following fires, 2 million cubic yards of mud are trapped, or about 200,000 dump trucks-worth. Beatty is one of 163 debris basins in the county, and was one of five debris basins in the area affected by the Colby Fire. The February/March rains that hit Heinlein’s home unleashed 60,000 cubic yards of mud into those five basins. Flood Maintenance hauled it out. A round of storms late last fall filled the basins with another 65,000-70,000 cubic yards of material. Flood Maintenance hauled it out. Just before Christmas, more rain came and the hills continued to spew mud, filling the Beatty basin with about 5,000 cubic yards of sediment.

It’s 9 a.m. and Flood Maintenance is hauling mud. The sediment pile is divided into three loading stations, where a revolving battalion of 34 dump trucks backs up to be loaded down by dozers and excavators, like a herd of robotic yellow elephants. A flagger choreographs the trucks into and out of the loading stations. I feel like I’ve entered a real-life Bob the Builder set.

“That’s a 400-pound rock,” says Ron Driggs, a second generation Flood Maintenance guy who got his first Public Works job at age 19. An excavator delivers a rock-studded mouthful of dirt into the bed of a blue dump truck, it drops with a tremendous clang. An uneven drop can rock a dump truck like a boat and give a driver whiplash. Dozers work the sides of the pile, tidying up material for the next round of dumps.

“Once it gets going it’s a well-oiled machine,” Driggs proudly states. The operation indeed has a harmony, an elbow-grease symphony of purring engines and droning hydraulics. As I watch it unfold, I can’t help but reflect that most L.A. County residents are kept safe behind barriers they don’t even know exist.

The Flood Maintenance guys like to say the city’s battle plan hasn’t changed much since 1934. Let the basins fill. Haul the debris out. But geologists continue to learn more about debris flows, whose underlying mechanisms remain shrouded in mystery.

At California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, geologist Michael Lamb is touring me around his airplane hangar-sized Earth Surface Dynamics Laboratory. “What we are doing is speeding up geologic time,” says Lamb excitedly. He is dressed in a crisp button-down and slacks, with finely combed hair. An ordered appearance, perhaps to counter the chaos of the phenomenon he is studying.

The lab is dominated by a pair of what appear to be free-standing mall escalators. These are flumes, mechanical stream beds that allow Lamb to alter slope, water speed, sediment size, and sediment quantity to assess just what makes rainy, recently burned hillsides shoot out rivers of mud. The flumes are rigged with fancy sensing equipment, including cameras, pressure gauges and even an ultrasound, to capture the internal structure of the lab-induced debris flows.

“There are ideas about how this all works,” says Lamb, “but the truth is, it is still a pretty big mystery. Where is the sediment coming from, and why is there suddenly a large change in the supply of sediment after a fire? We don’t know the full answer yet.”

Lamb’s research has highlighted two significant reasons that fires trigger debris flows. The San Gabriels are steep, with many slopes greater than 45 degrees, so sediment, which is not stable beyond slopes of 30 to 40 degrees, is continuously sliding down hillsides. Growing on these steep crumbly slopes is a community of plants, shrubs, and trees known as chaparral. Lamb has found that chaparral trees and bushes act as tiny dams, trapping sediment between their trunks and stems. But when the San Gabriel’s chaparral burns, which happens about once every 30 years, these tiny sediment traps are released. Soil is carried downhill by gravity and collects in flatter places, such as streambeds. With rain, that sediment begins moving. Flows pick up more sediment as they go, and rocks and boulders, too, then rush downhill as potentially deadly debris flows.

To truly crack the mountains’ endless assault on L.A., Lamb needs to understand exactly how much rain is necessary to get the soil accumulated in streambeds moving. A third flume in the rear of his lab helps him gain insight into how the Mississippi River Delta works. Deep rivers with low slopes are capable of carrying vast quantities of sediment within their water column—the Mississippi, for example, is not a debris flow, it is just a very muddy river. Yet on steep slopes, gravity doesn’t allow for deep rivers, meaning the swift shallow streams that develop don’t have the ability to move a lot of mud. When overwhelmed with fine sediment, a somewhat mysterious transition occurs and streams like those in the San Gabriels are transformed from currents of water to bucking, violent flows of mud, sand, gravel, “and boulders the size of cars,” says Lamb.

To illustrate this point, Lamb shows me a video of a rainy hillside in the Italian Alps. A swift-flowing valley stream is joined by a small debris flow shooting down a side canyon and instantaneously becomes a raging torrent of mud. “You see that!” Lamb exclaims as the flows merge. “We have no idea what is happening there.”

The tectonic-plate model is a reminder of the geologic forces churning beneath our feet. Life is not static. Nature will have its way.

But it has something to do with the influx of fine sediment transforming the channel into a concentrated debris flow. If Lamb could better understand this transition point, then at some point Flood Maintenance guys like Sheridan might know exactly when a recently burned hillside is going to release a river of mud. But to get there Lamb needs cameras on the hillsides. In Switzerland and Japan, pressure transducers and motion detectors in the beds of rivers allows researchers to determine whether a flow coming down a mountain is water or mud before it reaches an inhabited area. But the United States, laments Lamb, is lacking in publicly funded environmental monitoring. While the U.S. Geological Survey is ramping up a program to monitor debris flows in post-fire landscapes, and has placed sensing equipment in a few spots in the San Gabriels, Lamb says these monitoring stations are not permanent and not enough. “To get better predictions,” he says, “we need better data.”

Before I leave Caltech, I drop in on professor of geology and geophysics Joann Stock. We talk about the ultimate source of debris flows in the San Gabriel Mountains, the San Andreas Fault. On a model meant for middle-school students, she shows me how land west of the fault, including L.A., is being dragged northwest up the length of California by the Pacific Plate. Santa Barbara used to be down near San Diego, Monterrey used to be in the Mojave Desert. As the plate pulls this valuable sliver of land northwestward, mountain ranges are sprung up then chewed back down, inland seas born then silted over, the earth’s surface continuously crumpled or flattened, as if it were merely a living room carpet being pulled about by the family dog.

In 70 million years, this sliver will have been towed across the North Pacific Ocean and will smash into Alaska. When this happens, the massive mountain range formed by the collision will make the San Gabriels look like a string of sand castles. Nobody knows what the Pacific Coast, or for that matter, the entire Earth will look like in 70 million years. “We can’t predict the future,” says Stock with a smile.

Nevertheless, Stock’s model is a reminder of the geologic forces churning beneath our feet. Life is not static. Nature will have its way. Our sense of control is a story we tell ourselves in order to live, to paraphrase Joan Didion’s opening line of The White Album, her 1979 collection of essays about California.

Under the bright morning sun, I sit in the front seat of Christian Tiscareño’s glossy white dump truck. We are taking our haul of debris from the Beatty basin to one of the 25 Sediment Placement Sites peppered across L.A. County. Some material is terraced—seemingly precariously—on hillsides in the foothills, other material is placed in old gravel pits, which is where we’re headed, a tremendous rectangular hole about six miles from the basin called Manning Pit.

“How’s my apron?” he calls to a flagger, referring to the mesh tarp trucks must roll over their beds to keep sediment from flying out. A water truck, which wets roads within the basin and sharp speed bumps called shaker plates are other efforts aimed to keep dust down and quell residents concerned about large dirt-filled dump trucks rattling through their neighborhoods. “People get mad because supposedly we’re causing all this traffic,” says Tiscareño, as we weave through a sub-development. “But if we didn’t take care of this, these people’s homes could be getting smashed.”

We motor down city streets, passing Pepe’s Tacos, a row of those unbelievably skinny L.A. palms, a donut shop, pedestrians out with their dogs, and others on their way to work with coffees in hand. We enter the freeway, where our dump truck disappears into rush hour traffic, lost among the thousands—the millions—of other Angelenos embarking upon their morning routines, a stream like none other the world has ever known. It is a vehicle debris flow, and each vehicle represents a life, navigating its way through a world of obstacles to its own shiny sea.

At Manning Pit we join a line of blue, orange, and silver dump trucks and descend one by one down a steep track to the edge of a dirt cliff then drop our loads. The brown-black piles will be graded over by a dozer, the pit slowly filled, another strike by the mountain range, another successful block by Flood Maintenance. Leaving the pit I catch a glimpse of the San Gabriels, shining brilliantly above the freeway traffic, looking deceptively tranquil in the fine morning air. But I know they won’t stay still for long.

“This process will continue,” Driggs tells me back at Beatty, “from now until the end of time.”

Justin Nobel’s stories have been published in Best American Travel Writing 2011 and Best American Science and Nature Writing 2014. He is in the process of composing a book of travel stories titled North, South. He lives in New Orleans.