Simen Johan’s photographic series reads like an off-kilter field guide. Giraffes lose their heads in the fog, louche primates debauch with domestic animals, and tapestry-like camouflage both conceals and dazzles. Climate, habitat, and species are fragmented and remixed. To create the vivid images in his long-running series, “Until the Kingdom Comes,” Johan uses a grab bag of techniques and effects.

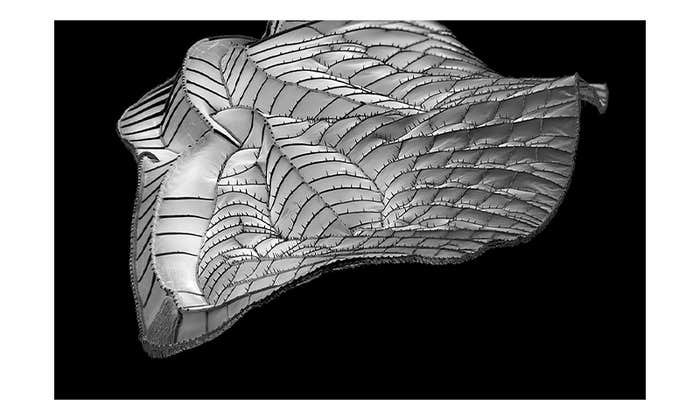

The near-life-sized images show animals in diverse locations: nature preserves, zoos, and dioramas at natural-history museums. Some take years to complete, involving intricate set building and post-production work. Others are mashups of multiple images of animals in various habitats, locations, and seasons. A few are simply straight photographs. It can be hard to know exactly what you are looking at, and that is just as the artist wants it.

There is a certain amount of visual problem-solving required to decipher these puzzling images. In the 1999 paper “The Science of Art,” neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran and philosopher William Hirstein wrote that understanding images involves perceptual grouping, to discriminate figures from backgrounds, and that this experience can be inherently satisfying to the human mind. Our eyes are also drawn to high-contrast parts of images, which tend to be information rich. Camouflage in nature works partly by taking advantage of these predictable processes. In “Until the Kingdom Comes,” camouflage is also used to trick us in a deeper way, confusing the plains with the jungle, one country with another, the real with the fake.

Johan suggests that his artistic impulse to cultivate uncertainty has its roots in his own life-changing experiences, including a snowboarding accident that left him in a coma for a short time. “Reality has this false sense of certitude that’s easy to take for granted, and I used to be heavily invested in it—my identity, goals, and whatever else—until certain events triggered me to see through the illusion,” he says. “There was a collapse in perceived meaning and purpose that haunted me for some time, but ultimately brought me deeper and helped me get a better sense of myself and the world.”

Through his work, the artist seeks to share a similar sense of destabilization with viewers, a reminder of the tenuousness of reality. The heightened, almost surgical precision of Johan’s images can both create and dispel illusions. His creatures may tease the eye, but the disorienting experience can lead to insight.

Johan’s work specifically raises questions about the distinction between the natural and artificial. The photos can at first glance seem like straightforward wildlife photography, but a closer look reveals the hand of the artist throughout. Yet if humans are animals, can we, or our art, be regarded as something divorced from nature? “If we saw ourselves as part of nature, not separate from it, that would increase our sense of responsibility,” Johan says. Likewise, we are subject to the same forces as the rest of the natural world. “There’s a code built into life to constantly improve upon itself; you see it both on a micro and on a macro level,” Johan says. “If humans fail, something else will take over.”

Rebecca Horne is a California-born, Brooklyn-based artist, writer, and multimedia producer.