Toward the end of the 18th century, in a wax workshop in Florence, a life-sized, anatomically correct, dissectible goddess of colored wax was created. Artist Clemente Susini took the idealized feminine beauty for which Italian artists had long been renowned in an ambitious new direction, and to hyper-realistic lengths. The result—an Anatomical Venus—is the perfect object: one whose luxuriously bizarre existence challenges belief. It—or better, she—was conceived as a means of teaching human anatomy without the need for constant dissection, which was messy, ethically fraught, and reliant on scarce cadavers. The Anatomical Venus also tacitly communicated the relationship between the human body and a divinely created cosmos, between art and science, and between nature and mankind, as it was then understood.

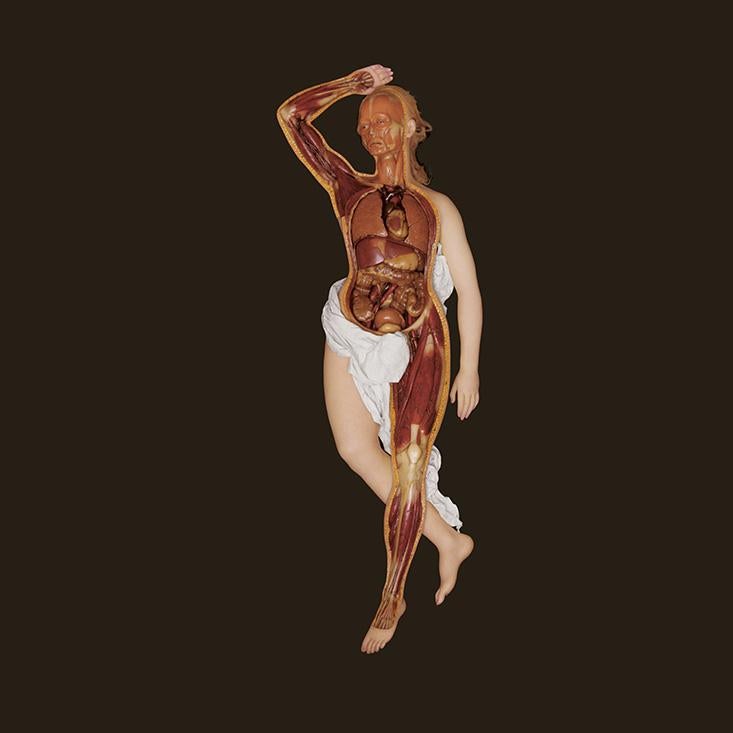

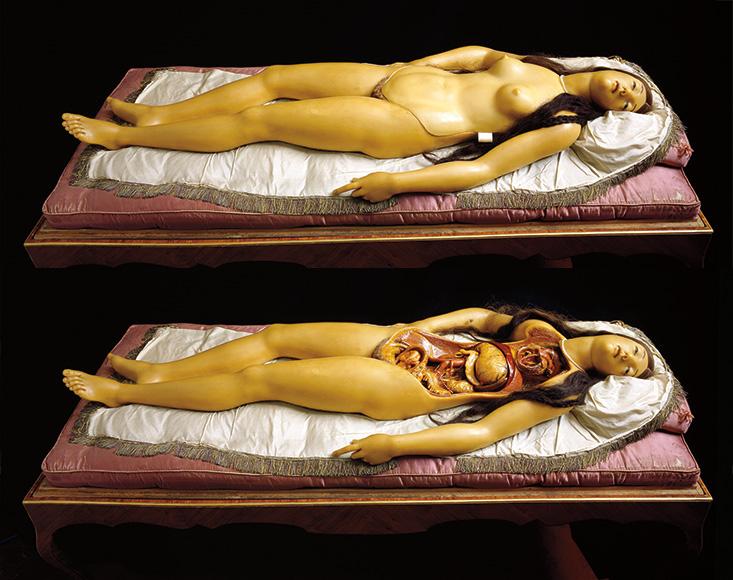

Often referred to as the “Medici Venus,” this life-sized, dissectible wax woman with gleaming glass eyes and human hair can still be viewed in her original Venetian glass and rosewood case. She can be disassembled into seven anatomically correct layers, revealing at the final remove a tranquil fetus curled in her womb. She and her sisters, wax women in fixed states of anatomical undress sometimes referred to as Slashed Beauties or Dissected Graces, can still be found in a handful of European museums. Supine in their glass boxes, they beckon with a gentle smile or an ecstatic downcast gaze. One idly toys with a plait of real golden human hair; another clutches at the plush, moth-eaten satin cushions of her case as her torso erupts in a spontaneous, bloodless auto-dissection; another is crowned with a golden tiara, while one further wears a silk ribbon tied in a bow around a dangling entrail.

Since their creation in late-18th-century Florence, these wax women have seduced, intrigued, and instructed. In the 21st century, they also confound, flickering on the edges of medicine and myth, votive and vernacular, fetish and fine art. How can we understand today an object that is at once a seductive representation of ideal female beauty and an explicit demonstration of the inner workings of the body? How can we make sense of an artifact that was once equally at home in the fairground and the medical museum? How can we comprehend a creature memorably described by Holly Myers in the Los Angeles Times as “an Enlightenment-era St. Teresa ravished by communion with the invisible forces of science”?

To the modern eye, the Medici Venus is a perplexing object‚ one that challenges conventions of scientific visualization and explodes neat, categorical divides between art and science, entertainment and education. In her own day, she was considered the ideal tool to teach anatomy to a general public, and she was so highly regarded by anatomists that copies were commissioned for a variety of museums and teaching collections around Europe. The Medici Venus was a perfect embodiment of the Enlightenment values of her time, in which human anatomy was understood as a reflection of the world and the pinnacle of divine knowledge, and in which to know the human body was to know the mind of God. Although she was neither the first nor the last of her kind, she was the most accomplished Anatomical Venus ever made, setting the standard by which all others are judged.

The Medici Venus was born in the workshop of The Museum for Physics and Natural History in Florence, better known as La Specola, a public science museum in Florence. Museum director Felice Fontana’s grand and ambitious aim was to create an encyclopedia of the human body in wax. Fontana hoped that it would end the need for cadavers in the teaching of anatomy: If we succeeded in reproducing in wax all the marvels of our animal machine, we would no longer need to conduct dissections, and students, physicians, surgeons, and artists would be able to find their desired models in a permanent, odor-free, and incorruptible state.

The wax models produced by the workshop at La Specola were posed as if alive, healthy, and pain-free, in an attempt to distance the study of anatomy from the contemplation of death and bloody internal organs. The Anatomical Venus was further removed from notions of death and the corpse as she drew on the historical and artistic figure of the Roman goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, evoking a long history of paintings and sculptures of placid, idealized nudes.

Each pristine wax model at the museum was the product of the careful study of cadavers that were delivered from the nearby Santa Maria Nuova hospital. Although the collection fell short of its ambition to render all further human dissection unnecessary, today, over 200 years after their creation, La Specola’s waxworks are still considered remarkably accurate, some of them demonstrating anatomical structures that had yet to be named or described at the time of their making.

Susini was the best known of all the wax artists employed at La Specola’s workshop, and it was under Susini’s oversight that the museum created its finest and most iconic works, among them the ingenious, dissectible Medici Venus.

The modelers who created the anatomical wax models at La Specola and other wax workshops depended in part for the veracity of their work on the anatomical illustrations featured in anatomical atlases. Real human body parts would then be procured to work from, in order to ensure that all the individual parts were as accurate as possible. An Anatomical Venus was expensive and time-consuming to produce. Over 200 cadavers were sometimes required to craft a single dissectible figure, owing to the speed with which bodies decayed, especially in the hot weather of the summer months.

The modeler would either take a cast of the prepared specimen or copy it by hand. Once a model of inexpensive wax or clay had been approved, a plaster cast would be taken to serve as a mold, which could then be used repeatedly.

Next, the plaster molds would be coated with soap or oil to ease release of the wax. Wax can look uncannily like flesh; it has a similarly moist appearance, depth of color (due to the even suspension of added pigments), and transparent opacity. The most commonly used waxes were beeswax; white “Virgin wax” from Smyrna or Venice; or that of the Chinese scale insects Ceroplastes ceriferus and Ericerus pela, which produce a particularly fine, hard, white wax with a high melting point, well suited to modeling skin, though prohibitively expensive. The wax would be mixed with turpentine and other oils or fats to produce the required texture, as well as a mastic, or plant resin, to fortify and increase its stability, which was important for sustaining structure and retaining vivid colors. It would then be carefully heated and colored with finely ground pigments, often highly precious or toxic, which had been sifted through cloth and dissolved in oil or turpentine.

Thin layers of tinted wax would then be painted into, cooled, and released from the mold. As most of the pieces were hollow, they were stuffed with rags or woodchips for support, although some, including Susini’s Medici Venus, have metal frames. Hair was attached with varnish; eyelashes were individually implanted. Fine blood vessels and nerves were made of silk or linen fibers dipped in wax. The parts would be assembled, while attending to any flaws or damage. Finally, the model would be glazed in order to keep its surfaces free of dust and affect a realistic shine: another anatomical masterwork ready for display.

The Medici Venus looks perplexing and sometimes even troubling to the contemporary eye, a response that is largely due to the startling juxtaposition between the abjectness of her innards and the erotic charge of her hyper-beautiful exterior. This odd sense is heightened by the inclusion of details that, to today’s sensibility, seem superfluous to her educational aims: her cascade of lustrous hair, life-like glass eyes, pearl necklace (a memento mori symbol that also covers the seam that attaches her head to her torso), and bed of luxurious silk and satin. Such artful and seductive details seem to undermine her scientific integrity, but it is the intertwining of anatomy, art, and religion that unlocks the meaning of her provocative appeal.

The Medici Venus’s enigmatic expression and swooning posture are suggestive of ecstasy, which today is understood as sexual. We can infer that at the time of her creation she was not regarded as particularly indecent from the fact that, upon opening to the general public, including women and children, the wax models were the most popular exhibits, eliciting neither criticism nor public outcry. There are scores of comments by visitors to the museum who spoke highly of the collection, and we know that copies were commissioned by a variety of other museums. Clearly, something has changed since the time of Venus’s creation in such a way as to render her strange and sexually charged. It is likely that a different understanding of the ecstatic than our own influenced Venus’s reception. The ecstatic was understood at that time not merely as a profane, sensual experience, but as an expression of the sacred: a mystical experience. Depictions of saints and martyrs in attitudes of ecstatic release fill the churches of Italy and other Catholic countries.

But how are we to understand such ecstatic representations today? Perhaps the heart of the confusion lies in the notion of the ecstatic as either religious or sexual, sacred or profane, where once it was understood to be both. In Georges Bataille’s 1957 Eroticism, he argues that sexuality itself was a part of religious expression until Christianity banished it from that domain. The very etymology of the word ecstasy lies in the Greek ek, meaning “out of,” and stasis, meaning “standing.” This escape from isolated consciousness is experienced as a sort of transcendent bliss beyond the powers of language or description. It is, in Bataille’s words, “divine life sought through death of the self” that is at the heart of the ecstatic experience. It is our way of returning to the state of grace that existed before we were banished from the Garden of Eden; before we were divided from the universe by our self-awareness, our language and propensity for abstraction, our sense of shame, and the foreknowledge of our own death—arguably the very thing that separates us from other animals. This is the enlightened epiphany described by mystics of all religious backgrounds. It is no wonder that sexuality retains a touch of the supernatural, if rendered strange by our attempts to focus it squarely in the world of the body and the senses, and to separate it from more mysterious domains.

Only a little over 200 years ago the Medici Venus was the perfect tool to teach human anatomy to the public; today she is bizarre—an alluring, life-like female wax model in a state of ambiguous ecstasy with her inner organs on graphic display. Perhaps she could only be truly understood for a brief period, a time when it was still possible for religion, art, philosophy, and science to coexist peacefully; she is a relic from an age in which the torch was passed from spirituality to science as the primary arbiter of death, disease, the nature of life, and humanity’s place in the universe. But maybe we are drawn today to the Anatomical Venus because of an unspoken, intuited resolution of our own divided nature, an unconscious recognition of another avenue abandoned, in which beauty and science, religion and medicine, soul and body might be one.

Joanna Ebenstein is a multidisciplinary artist, curator, writer, lecturer, and graphic designer. She is also the co-founder and creative director of the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn, New York.

Adapted from The Anatomical Venus by Joanna Ebenstein, published by Thames & Hudson LTD. Copyright © 2016 Joanna Ebenstein