The dazed young woman who arrived at Sunnybrook Hospital, Canada’s first and largest regional trauma center, from a head-on car crash presented the surgeons treating her with a disturbing problem. In addition to her many broken bones, the rhythm of her heartbeat had become wildly irregular. It was either skipping beats or adding extra beats; in any case, she had more than one thing seriously wrong with her.

She remained alert enough to tell them that she had a past history of an overactive thyroid. An overactive thyroid can cause an irregular heartbeat. And so, when the hospital’s resident medical detective, Don Redelmeier, arrived, the staff believed that they no longer needed him to investigate the source of the irregular heartbeat but only to treat it. No one in the operating room would have batted an eye if Redelmeier had simply administered the drugs for hyperthyroidism. Instead, Redelmeier asked everyone to slow down. To wait. Just a moment. Just to check their thinking—and to make sure they were not trying to force the facts into an easy, coherent, but ultimately false story.

Something bothered him. As he said later, “Hyperthyroidism is a classic cause of an irregular heart rhythm, but hyperthyroidism is an infrequent cause of an irregular heart rhythm.” Hearing that the young woman had a history of excess thyroid hormone production, the emergency room medical staff had leaped, with seeming reason, to the assumption that her overactive thyroid had caused the dangerous beating of her heart. They hadn’t bothered to consider statistically far more likely causes of an irregular heartbeat. In Redelmeier’s experience, doctors did not think statistically. “Eighty percent of doctors don’t think probabilities apply to their patients,” he said. “Just like 95 percent of married couples don’t believe the 50-percent divorce rate applies to them, and 95 percent of drunk drivers don’t think the statistics that show that you are more likely to be killed if you are driving drunk than if you are driving sober applies to them.”

Redelmeier’s job in the trauma center was, in part, to check the understanding of the specialists for mental errors. “It isn’t explicit but it’s acknowledged that he will serve as a check on other people’s thinking,” said Rob Fowler, an epidemiologist at Sunnybrook. “About how people do their thinking. He keeps people honest. The first time people interact with him they’ll be taken aback: Who the hell is this guy, and why is he giving me feedback? But he’s lovable, at least the second time you meet him.” That Sunnybrook’s doctors had come to appreciate the need for a person to serve as a check on their thinking, Redelmeier thought, was a sign of how much the profession had changed since he entered it in the mid-1980s. When he’d started out, doctors set themselves up as infallible experts; now there was a place in Canada’s leading regional trauma center for a connoisseur of medical error. A hospital was now viewed not just as a place to treat the unwell but also as a machine for coping with uncertainty. “Wherever there is uncertainty there has got to be judgment,” said Redelmeier, “and wherever there is judgment there is an opportunity for human fallibility.”

Across the United States, more people died every year as a result of preventable accidents in hospitals than died in car crashes—which was saying something. Bad things happened to patients, Redelmeier often pointed out, when they were moved without extreme care from one place in a hospital to another. Bad things happened when patients were treated by doctors and nurses who had forgotten to wash their hands. Bad things even happened to people when they pressed hospital elevator buttons. Redelmeier had actually co-written an article about that: “Elevator Buttons as Unrecognized Sources of Bacterial Colonization in Hospitals.” For one of his studies, he had swabbed 120 elevator buttons and 96 bathroom surfaces at three big Toronto hospitals and produced evidence that the elevator buttons were far more likely to infect you with some disease.

Of all the bad things that happened to people in hospitals, the one that most preoccupied Redelmeier was clinical misjudgment. Doctors and nurses were human, too. They sometimes failed to see that the information patients offered them was unreliable—for instance, patients often said that they were feeling better, and might indeed believe themselves to be improving, when they had experienced no real change in their condition. Doctors tended to pay attention mainly to what they were asked to pay attention to, and to miss some bigger picture. They sometimes failed to notice what they were not directly assigned to notice. “One of the things Don taught me was the value of observing the room when the patient isn’t there,” says Jon Zipursky, former chief medical resident at Sunnybrook. “Look at their meal tray. Did they eat? Did they pack for a long stay or a short one? Is the room messy or neat? Once we walked into the room and the patient was sleeping. I was about to wake him up and Don stops me and says, ‘There is a lot you can learn about people from just watching.’ ”

Doctors tended to see only what they were trained to see: That was another big reason bad things might happen to a patient inside a hospital. A patient received treatment for something that was obviously wrong with him, from a specialist oblivious to the possibility that some less obvious thing might also be wrong with him. The less obvious thing, on occasion, could kill a person.

Redelmeier asked the emergency room staff to search for other, more statistically likely causes of the woman’s irregular heartbeat. That’s when they found her collapsed lung. Like her fractured ribs, her collapsed lung had failed to turn up on the X-ray. Unlike the fractured ribs, it could kill her. Redelmeier ignored the thyroid and treated the collapsed lung. The young woman’s heartbeat returned to normal. The next day, her formal thyroid tests came back: Her thyroid hormone production was perfectly normal. Her thyroid had never been the issue. It was a classic case of what Redelmeier would soon come to know as the “representativeness heuristic.” “You need to be so careful when there is one simple diagnosis that instantly pops into your mind that beautifully explains everything all at once,” he said. “That’s when you need to stop and check your thinking.”

Redelmeier had grown up in Toronto. The youngest of three boys, he often felt a little stupid; his older brothers always seemed to know more than he did and were keen to let him know it. Redelmeier also had a speech impediment—a maddening stutter he would never cease to work hard, and painfully, to compensate for. His stutter slowed him down when he spoke; his weakness as a speller slowed him down when he wrote. His two great strengths were his mind and his temperament. He was always extremely good at math; he loved math. He could explain it, too, and other kids came to him when they couldn’t understand what the teacher had said. That is where his temperament entered. He was almost peculiarly considerate of others. From the time he was a small child, grown-ups had noticed that about him: His first instinct upon meeting someone else was to take care of the person. Still, even from math class, where he often wound up helping all the other students, what he took away was a sense of his own fallibility. In math there was a right answer and a wrong answer, and you couldn’t fudge it. “And the errors are sometimes predictable,” he said. “You see them coming a mile away and you still make them.” His experience of life as an error-filled sequence of events, he later thought, might be what had made him so receptive to an obscure article, in the journal Science, that his favorite high school teacher, Mr. Fleming, had given him to read in late 1977. He took the article home with him and read it that night at his desk. The article was called “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” It was by two psychologists at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

Amos Tversky and Danny Kahneman had been collaborating since 1969, when they wrote a paper together called “Belief in the Law of Small Numbers,” which exposed a common flaw in human statistical reasoning. In 1970, Amos left Jerusalem to spend a year at Stanford University; Danny stayed behind. They used the year apart to collect data about how people form statistical judgments. The data consisted entirely of answers to curious questions that they had devised.

Consider the following question:

All families of six children in a city were surveyed. In 72 families the exact order of births of boys and girls was G B G B B G. What is your estimate of the number of families surveyed in which the exact order of births was B G B B B B?

That is, in this hypothetical city, if there were 72 families with six children born in the following order—girl, boy, girl, boy, boy, girl—how many families with six children do you imagine have the birth order boy, girl, boy, boy, boy, boy? Who knows what Israeli high school students made of the strange question, but 1,500 of them supplied answers to it. The researchers posed other, equally weird, questions to college students at the University of Michigan and Stanford University. For example:

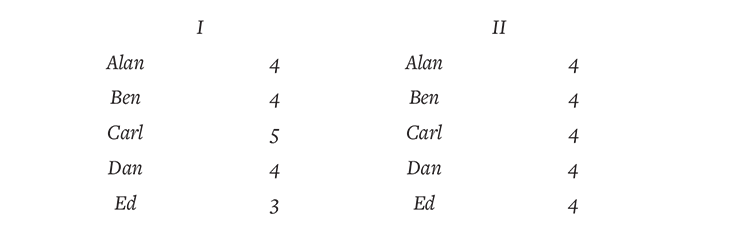

On each round of a game, 20 marbles are distributed at random among five children: Alan, Ben, Carl, Dan, and Ed. Consider the following distributions:

In many rounds of the game, will there be more results of type I or type II?

They were trying to determine how people judged—or, rather, misjudged—the odds of any situation when the odds were hard, or impossible, to know. All the questions had right answers and wrong answers. The answers that their subjects supplied could be compared to the right answer, and their errors investigated for patterns. “The general idea was: What do people do?” Danny later said. “What actually is going on when people judge probability? It’s a very abstract concept. They must be doing something.”

Amos and Danny didn’t have much doubt that a lot of people would get the questions they had dreamed up wrong—because Danny and Amos had gotten them, or versions of them, wrong. If they both committed the same mental errors, or were tempted to commit them, they assumed—rightly, as it turned out—that most other people would commit them, too. The questions they had spent the year cooking up were not so much experiments as they were little dramas: Here, look, this is what the uncertain human mind actually does.

Their first paper had shown that people faced with a problem that had a statistically correct answer did not think like statisticians. Even statisticians did not think like statisticians. “Belief in the Law of Small Numbers” had raised an obvious next question: If people did not use statistical reasoning, even when faced with a problem that could be solved with statistical reasoning, what kind of reasoning did they use? Their next paper offered a partial answer to the question. It was called “Subjective Probability: A Judgment of Representativeness.”

“Subjective probability” meant the odds you assign to any given situation when you are more or less guessing. Look outside the window at midnight and see your teenage son weaving his way toward your front door, and say to yourself, “There’s a 75 percent chance he’s been drinking”—that’s subjective probability. “Subjective probabilities play an important role in our lives,” they began. “The decisions we make, the conclusions we reach, and the explanations we offer are usually based on our judgments of the likelihood of uncertain events such as success in a new job, the outcome of an election, or the state of the market.” In these and many other uncertain situations, the mind did not naturally calculate the correct odds. So what did it do? It replaced the laws of chance with rules of thumb. These rules of thumb Danny and Amos called “heuristics.” And the first heuristic they wanted to explore they called “representativeness.”

When people make judgments, they argued, they compare whatever they are judging to some model in their minds. How much do those clouds resemble my mental model of an approaching storm? How closely does this ulcer resemble my mental model of a malignant cancer? Does Jeremy Lin match my mental picture of a future NBA player? Does that belligerent German political leader resemble my idea of a man capable of orchestrating genocide? The world’s not just a stage. It’s a casino, and our lives are games of chance. And when people calculate the odds in any life situation, they are often making judgments about similarity—or representativeness. You have some notion of a parent population: “storm clouds” or “gastric ulcers” or “genocidal dictators” or “NBA players.” You compare the specific case to the parent population.

The more easily people can call a scenario to mind, the more probable they find it.

“Our thesis,” they wrote, “is that, in many situations, an event A is judged more probable than an event B whenever A appears more representative than B.” The more the basketball player resembles your mental model of an NBA player, the more likely you will think him to be an NBA player. They had a hunch that people, when they formed judgments, weren’t just making random mistakes—that they were doing something systematically wrong.

The problem was subtle. The rule of thumb they had called representativeness wasn’t always wrong. If the mind’s approach to uncertainty was occasionally misleading, it was because it was often so useful. Much of the time, the person who can become a good NBA player matches up pretty well with the mental model of “good NBA player.” But sometimes a person does not—and in the systematic errors they led people to make, you could glimpse the nature of these rules of thumb.

For instance, in families with six children, the birth order B G B B B B was about as likely as G B G B B G. But Israeli kids—like pretty much everyone else on the planet, it would emerge—naturally seemed to believe that G B G B B G was a more likely birth sequence. Why? “The sequence with five boys and one girl fails to reflect the proportion of boys and girls in the population,” they explained. It was less representative. What is more, if you asked the same Israeli kids to choose the more likely birth order in families with six children—B B B G G G or G B B G B G—they overwhelmingly opted for the latter. But the two birth orders are equally likely. So why did people almost universally believe that one was far more likely than the other? Because, said Danny and Amos, people thought of birth order as a random process, and the second sequence looks more “random” than the first.

The natural next question: When does our rule-of-thumb approach to calculating the odds lead to serious miscalculation? One answer was: whenever people are asked to evaluate anything with a random component to it. For example, Londoners in World War II thought that German bombs were targeted, because some parts of the city were hit repeatedly while others were not hit at all. (Statisticians later showed that the distribution was exactly what you would expect from random bombing.) People find it a remarkable coincidence when two students in the same classroom share a birthday, when in fact there is a better than even chance, in any group of 23 people, that two of its members will have been born on the same day. We have a kind of stereotype of “randomness” that differs from true randomness. Our stereotype of randomness lacks the clusters and patterns that occur in true random sequences. If you pass out 20 marbles randomly to five boys, they are actually more likely to each receive four marbles (column II), than they are to receive the combination in column I, and yet college students insisted that the unequal distribution in column I was more likely than the equal one in column II. Why? Because column II “appears too lawful to be the result of a random process.”

Danny and Amos believed that these errors had larger implications. “In their daily lives,” they wrote, “people ask themselves and others questions such as: What are the chances that this 12-year-old boy will grow up to be a scientist? What is the probability that this candidate will be elected to office? What is the likelihood that this company will go out of business?” They confessed that they had confined their questions to situations in which the odds could be objectively calculated. But they felt fairly certain that people made the same mistakes when the odds were harder, or even impossible, to know. When, say, they guessed what a little boy would do for a living when he grew up, they thought in stereotypes. If he matched their mental picture of a scientist, they guessed he’d be a scientist—and neglect the prior odds of any kid becoming a scientist.

In a later paper, Amos and Danny described a second “heuristic.” It was called “Availability: A Heuristic for Judging Frequency and Probability.” In one example, the authors asked:

The frequency of appearance of letters in the English language was studied. A typical text was selected, and the relative frequency with which various letters of the alphabet appeared in the first and third positions in words was recorded. Words of less than three letters were excluded from the count.

You will be given several letters of the alphabet, and you will be asked to judge whether these letters appear more often in the first or in the third position, and to estimate the ratio of the frequency with which they appear in these positions. …

Consider the letter K. Is K more likely to appear in:

the first position?

the third position? (check one)

My estimate for the ratio of these two values is: __ : 1

If you thought that K was, say, twice as likely to appear as the first letter of an English word than as the third letter, you checked the first box and wrote your estimate as 2:1. This was what the typical person did, as it happens. Danny and Amos replicated the demonstration with other letters—R, L, N, and V. Those letters all appeared more frequently as the third letter in an English word than as the first letter—by a ratio of two to one. Once again, people’s judgment was, systematically, very wrong. And it was wrong, Danny and Amos now proposed, because it was distorted by memory. It was simply easier to recall words that start with K than to recall words with K as their third letter. The more easily people can call some scenario to mind—the more available it is to them—the more probable they find it to be.

The point, once again, wasn’t that people were stupid. This particular rule they used to judge probabilities (the easier it is for me to retrieve from my memory, the more likely it is) often worked well. But if you presented people with situations in which the evidence they needed to judge them accurately was hard for them to retrieve from their memories, and misleading evidence came easily to mind, they made mistakes. “Consequently,” Amos and Danny wrote, “the use of the availability heuristic leads to systematic biases.” Human judgment was distorted by … the memorable.

For Don Redelmeier, Kahneman and Tversky’s work was in equal parts familiar and strange. Redelmeier was 17 years old, and some of the jargon was beyond him. But the article described the ways in which people made judgments when they didn’t know the answer for sure. They made the phenomenon they described feel like secret knowledge. Yet what they were saying struck Redelmeier as the simple truth—mainly because he was fooled by the questions they put to the reader. He, too, thought that there were more words in a typical passage of English prose that started with K than had K in the third position, because the words that began with K were easier to recall.

What struck Redelmeier wasn’t the idea that people made mistakes. Of course people made mistakes! What was so compelling is that the mistakes were predictable and systematic. They seemed ingrained in human nature. One passage in particular stuck with him—about the role of the imagination in human error. “The risk involved in an adventurous expedition, for example, is evaluated by imagining contingencies with which the expedition is not equipped to cope,” the authors wrote. “If many such difficulties are vividly portrayed, the expedition can be made to appear exceedingly dangerous, although the ease with which disasters are imagined need not reflect their actual likelihood. Conversely, the risk involved in an undertaking may be grossly underestimated if some possible dangers are either difficult to conceive of, or simply do not come to mind.” This wasn’t just about how many words in the English language started with the letter K. This was about life and death.

As a kid, Redelmeier hadn’t had much trouble figuring out what he wanted to do with his life. He’d fallen in love with the doctors on television—Leonard McCoy on Star Trek and, especially, Hawkeye Pierce on M*A*S*H. “I sort of wanted to be heroic,” he said. “I would never cut it in sports. I would never cut it in politics. I would never make it in the movies. Medicine was a path. A way to have a truly heroic life.” He felt the pull so strongly that he applied to medical school at the age of 19, during his second year of college. Just after his 20th birthday he was training at the University of Toronto to become a doctor.

And that’s where the problems started: “Early on in medical school there are a whole bunch of professors who are saying things that are wrong,” Redelmeier recalled. “I don’t dare say anything about it.” They repeated common superstitions as if they were eternal truths. (“Bad things come in threes.”) Specialists from different fields of medicine faced with the same disease offered contradictory diagnoses. His professor of urology told students that blood in the urine suggested a high chance of kidney cancer, while his professor of nephrology said that blood in the urine indicated a high chance of glomerulonephritis—kidney inflammation. “Both had exaggerated confidence based on their expert experience,” said Redelmeier, and both mainly saw only what they had been trained to see.

The world’s not just a stage. It’s a casino.

The problem was not what they knew, or didn’t know. It was their need for certainty or, at least, the appearance of certainty. Standing beside the slide projector, many of them did not so much teach as preach. “There was a generalized mood of arrogance,” said Redelmeier. “ ‘What do you mean you didn’t give steroids!!????’ ” To Redelmeier the very idea that there was a great deal of uncertainty in medicine went largely unacknowledged by its authorities.

There was a reason for this: To acknowledge uncertainty was to admit the possibility of error. The entire profession had arranged itself as if to confirm the wisdom of its decisions. Whenever a patient recovered, for instance, the doctor typically attributed the recovery to the treatment he had prescribed, without any solid evidence that the treatment was responsible. Just because the patient is better after I treated him doesn’t mean he got better because I treated him, Redelmeier thought. “So many diseases are self-limiting,” he said. “They will cure themselves. People who are in distress seek care. When they seek care, physicians feel the need to do something. You put leeches on; the condition improves. And that can propel a lifetime of leeches. A lifetime of overprescribing antibiotics. A lifetime of giving tonsillectomies to people with ear infections. You try it and they get better the next day and it is so compelling. You go to see a psychiatrist and your depression improves—you are convinced of the efficacy of psychiatry.”

Redelmeier noticed other problems, too. His medical school professors took data at face value that should have been inspected more closely, for example. An old man would come into the hospital suffering from pneumonia. They’d check his heart rate and find it to be a reassuringly normal 75 beats per minute … and just move on. But the reason pneumonia killed so many old people was its power to spread infection. An immune system responding as it should generated fever, coughs, chills, sputum—and a faster than normal heartbeat. A body fighting an infection required blood to be pumped through it at a faster than normal rate. “The heart rate of an old man with pneumonia is not supposed to be normal!” said Redelmeier. “It’s supposed to be ripping along!” An old man with pneumonia whose heart rate appears normal is an old man whose heart may well have a serious problem. But the normal reading on the heart rate monitor created a false sense in doctors’ minds that all was well. And it was precisely when all seemed well that medical experts “failed to check themselves.”

When subjected to scientific investigation, some of what passed for medical wisdom turned out to be shockingly wrong-headed. When Redelmeier entered medical school in 1980, for instance, the conventional wisdom held that if a heart attack victim suffered from some subsequent arrhythmia, you gave him drugs to suppress it. By the end of Redelmeier’s medical training, in 1991, researchers had shown that heart attack patients whose arrhythmia was suppressed died more often than the ones whose condition went untreated. No one explained why doctors, for years, had opted for a treatment that systematically killed patients—though proponents of evidence-based medicine were beginning to look to the work of Kahneman and Tversky for possible explanations. But it was clear that the intuitive judgments of doctors could be gravely flawed: The evidence of the medical trials now could not be ignored. “I became very aware of the buried analysis—that a lot of the probabilities were being made up by expert opinion,” said Redelmeier. “I saw error in the way people think that was being transmitted to patients. And people had no recognition of the mistakes that they were making. I had a little unhappiness, a little dissatisfaction, a sense that all was not right in the state of Denmark.”

Toward the end of their article in Science, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky had pointed out that, while statistically sophisticated people might avoid the simple mistakes made by less savvy people, even the most sophisticated minds were prone to error. As they put it, “their intuitive judgments are liable to similar fallacies in more intricate and less transparent problems.” That, the young Redelmeier realized, was a “fantastic rationale why brilliant physicians were not immune to these fallibilities.” Error wasn’t necessarily shameful; it was merely human. “They provided a language and a logic for articulating some of the pitfalls people encounter when they think. Now these mistakes could be communicated. It was the recognition of human error. Not its denial. Not its demonization. Just the understanding that they are part of human nature.”

In 1985, Redelmeier was accepted as a medical resident at the Stanford University hospital. By the age of 27, as he finished his Stanford residency, Redelmeier was creating the beginnings of a worldview that internalized the article by the two Israeli psychologists that he had read as a teenager. Where this worldview would lead he did not know. He still thought it possible that, upon his return to Canada, he might just move back up to northern Labrador, where he had spent one summer during medical school delivering health care to a village of 500 people. “I didn’t have great memory skills or great dexterity,” he said. “I was afraid I wouldn’t be a great doctor. And if I wasn’t going to be great, I might as well go to serve someplace that was underserved, where I was needed and wanted.” Redelmeier actually still believed that he might wind up practicing medicine in a conventional manner. But then he met Amos Tversky.

In the spring of 1988, two days before his first lunch with Amos Tversky, Redelmeier walked through the Stanford Faculty Club dining room where they were scheduled to meet. He didn’t eat breakfast usually, but on this day he did, so that he wouldn’t overeat during lunch. Hal Sox, Redelmeier’s superior at Stanford, who would be joining them, had told Redelmeier, “Don’t talk. Don’t say anything. Don’t interrupt. Just sit and listen.” Meeting with Amos Tversky, Hal Sox, said, was “like brainstorming with Albert Einstein. He is one for the ages—there won’t ever be anyone else like him.”

Hal Sox happened to have co-authored the first article Amos ever wrote about medicine. Their paper had sprung from a question Amos had put to Sox: How did a tendency people exhibited when faced with financial gambles play itself out in the minds of doctors and patients? Specifically, given a choice between a sure gain and a bet with the same expected value (say, $100 for sure or a 50-50 shot at winning $200), Amos had explained to Hal Sox, people tended to take the sure thing. A bird in the hand. But, given the choice between a sure loss of $100 and a 50-50 shot of losing $200, they took the risk. With Amos’ help, Sox and two other medical researchers designed experiments to show how differently both doctors and patients made choices when those choices were framed in terms of losses rather than gains.

Lung cancer proved to be a handy example. Lung cancer doctors and patients in the early 1980s faced two unequally unpleasant options: surgery or radiation. Surgery was more likely to extend your life, but, unlike radiation, it came with the small risk of instant death. When you told people that they had a 90 percent chance of surviving surgery, 75 percent of patients opted for surgery. But when you told them that they had a 10 percent chance of dying from the surgery—which was, of course, just a different way of putting the same odds—only 52 percent chose the surgery. People facing a life-and-death decision responded not to the odds but to the way the odds were described to them. And not just patients; doctors did it, too. Working with Amos, Sox said, had altered his view of his own profession. “The cognitive aspects are not at all understood in medicine,” he said. Among other things, he could not help but wonder how many surgeons, consciously or unconsciously, had told some patient that he had a 90 percent chance of surviving a surgery, rather than a 10 percent chance of dying from it, simply because it was in his interest to perform the surgery.

Think what no one else has ever thought.

At that first lunch, Redelmeier mainly just watched as Sox and Amos talked. Still, he noticed some things. Amos’ pale blue eyes darted around, and he had a slight speech impediment. His English was fluent but spoken with a thick Israeli accent. “He was a little bit hypervigilant,” said Redelmeier. “He was bouncy. Energetic. He had none of the lassitude of some of the tenured faculty. He did 90 percent of the talking. Every word was worth listening to. I was surprised by how little medicine he knew, because he was already having a big effect on medical decision making.” Amos had all sorts of questions for the two doctors; most of them had to do with probing for illogic in medical behavior. After watching Hal Sox answer or try to answer Amos’ questions, Redelmeier realized that he was learning more about his superior in a single lunch than he’d gathered from the previous three years. “Amos knew exactly what questions to ask,” said Redelmeier.

At the end of the lunch, Amos invited Redelmeier to visit him in his office. It didn’t take long before Amos was bouncing ideas about the human mind off Redelmeier, to listen for an echo in medicine. The Samuelson bet, for instance. The Samuelson bet was named for Paul Samuelson, the economist who had cooked it up. As Amos explained it, people offered a single bet in which they have a 50-50 chance to either win $150 or lose $100 usually decline it. But if you offer those same people the chance to make the same bet 100 times over, most of them accept the bet. Why did they make the expected value calculation—and respond to the odds being in their favor—when they were allowed to make the bet 100 times, but not when they were offered a single bet? The answer was not entirely obvious. Yes, the more times you play a game with the odds in your favor, the less likely you are to lose; but the more times you play, the greater the total sum of money you stand to lose. Anyway, after Amos finished explaining the paradox, “he said, ‘Okay, Redelmeier, find me the medical analogy to that!’ ”

For Redelmeier, medical analogies popped quickly to mind. “Whatever the general example was, I knew a bunch of instantaneous medical examples. It was just astonishing that he would shut up and listen to me.” A medical analogy of Samuelson’s bet, Redelmeier decided, could be found in the duality in the role of the physician. “The physician is meant to be the perfect agent for the patient as well as the protector of society,” he said. “Physicians deal with patients one at a time, whereas health policy makers deal with aggregates.”

But there was a conflict between the two roles. The safest treatment for any one patient, for instance, might be a course of antibiotics; but the larger society suffers when antibiotics are overprescribed and the bacteria they were meant to treat evolve into versions of themselves that are more dangerous and difficult to treat. A doctor who did his job properly really could not just consider the interests of the individual patient; he needed to consider the aggregate of patients with that illness. The issue was even bigger than one of public health policy. Doctors saw the same illness again and again. Treating patients, they weren’t merely making a single bet; they were being asked to make that same bet over and over again. Did doctors behave differently when they were offered a single gamble and when they were offered the same gamble repeatedly?

The paper subsequently written by Amos with Redelmeier showed that, in treating individual patients, the doctors behaved differently than they did when they designed ideal treatments for groups of patients with the same symptoms. To avoid troubling issues, they were likely to order additional tests, and less likely to ask if patients wished to donate their organs if they died. In treating individual patients, doctors often did things they would disapprove of if they were creating a public policy to treat groups of patients with the exact same illness. “This result is not just another manifestation of the conflict between the personal interests of the individual patient and the general interests of society,” Tversky and Redelmeier wrote in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. “The discrepancy between the aggregate and the individual perspectives exists in the mind of the physician. The discrepancy seems to call for a resolution; it is odd to endorse a treatment for every case and reject it in general, or vice versa.”

The point was not that the doctor was incorrectly or inadequately treating individual patients. The point was that he could not treat his patient one way, and groups of patients suffering from precisely the same problem in another way, and be doing his best in both cases. And the point was obviously troubling—at least to the doctors who flooded the New England Journal of Medicine with letters written in response to the article. “Most physicians try to maintain this facade of being rational and scientific and logical and it’s a great lie,” said Redelmeier. “A partial lie. What leads us is hopes and dreams and emotion.”

Redelmeier’s first article with Amos led to other ideas. Soon they were meeting not in Amos’ office in the afternoon but at Amos’ home late at night. Working with Amos wasn’t work. “It was pure joy,” said Redelmeier. “Pure fun.” Redelmeier knew at some deep level that he was in the presence of a person who would change his life. Many sentences popped out of Amos’ mouth that Redelmeier knew he would forever remember:

A part of good science is to see what everyone else can see but think what no one else has ever thought.

So many problems occur when people fail to be obedient when they are supposed to be obedient, and fail to be creative when they are supposed to be creative.

It is sometimes easier to make the world a better place than to prove you have made the world a better place.

The man was so vivid that you could not confront any question without wondering how he would approach it. And yet, as Amos always seemed to have all the big ideas, and simply needed medical examples to illustrate them, Redelmeier was left with the feeling that maybe he hadn’t done very much. “In many ways I was a glorified secretary, and that troubled me for many years,” he said. “Deep down, I thought I was extremely replaceable. When I came back to Toronto, I wondered: Was it just Amos? Or was there something Redelmeier?”

Still, only a few years earlier, he’d imagined that he might wind up a general practitioner in a small village in northern Labrador. Now he had a particular ambition: to explore, as both researcher and doctor, the mental mistakes that doctors and their patients made. He wanted to combine cognitive psychology, as practiced by Danny and Amos, with medical decision making. How exactly he would do this he could not immediately say. All he knew for sure was that by working with Amos Tversky, he had discovered this other side to himself: a seeker of truth.

Years later, Don Redelmeier still heard the sound of Amos in his head. He’d been back from Stanford for several years, but Amos’ voice was so clear and overpowering that it made it hard for Redelmeier to hear his own. Redelmeier could not pinpoint the precise moment that he sensed that his work with Amos was not all Amos’ doing—that it had some Redelmeier in it, too. His sense of his own distinct value began with a simple question—about homeless people. The homeless were a notorious drag on the local health care system. They turned up in emergency rooms more often than they needed to. They were a drain on resources. Every nurse in Toronto knew this: If you see a homeless person wander in, hustle him out the door as fast as you can. Redelmeier wondered about the wisdom of that strategy.

And so, in 1991, he created an experiment. He arranged for large numbers of college students who wanted to become doctors to be given hospital greens and a place to sleep near the emergency room. Their job was to serve as concierges to the homeless. When a homeless person entered the emergency room, they were to tend to his every need. Fetch him juice and a sandwich, sit down and talk to him, help arrange for his medical care. The college students worked for free. They loved it: They got to pretend to be doctors. But they serviced only half of the homeless people who entered the hospital. The other half received the usual curt and dismissive service from the nursing staff. Redelmeier then tracked the subsequent use of the Toronto health care system by all the homeless people who had visited his hospital. Unsurprisingly, the group that received the gold-plated concierge service tended to return slightly more often to the hospital where they had received it than the unlucky group. The surprise was that their use of the greater Toronto health care system declined. When homeless people felt taken care of by a hospital, they didn’t look for other hospitals that might take care of them. The homeless said, “That was the best that can be done for me.” The entire Toronto health care system had been paying a price for its attitude to the homeless.

A part of good science is to see what everyone else can see but think what no one else has ever thought. Amos had said that to him, and it had stuck in Redelmeier’s mind. For instance, one day he had a phone call from an AIDS patient who was suffering side effects of medication. In the middle of the conversation, the patient cut him off and said, “I’m sorry, Dr. Redelmeier, I have to go. I just had an accident.” The guy had been talking to him on a cell phone while driving. Redelmeier wondered: Did talking on a cell phone while driving increase the risk of accident?

In 1993, he and Stanford statistician Robert Tibshirani created a complicated study to answer the question. The paper they published in 1997 proved that talking on a cell phone while driving was as dangerous as driving with a blood alcohol level at the legal limit. A driver talking on a cell phone was about four times as likely as a driver who wasn’t to be involved in a crash, whether or not he held the phone in his hands. That paper—the first to establish, rigorously, the connection between cell phones and car accidents—spurred calls for regulation around the world. It would take another, even more complicated study to determine just how many thousands of lives it saved.

The study also piqued Redelmeier’s interest in what happened inside the mind of a person behind the wheel of a car. The doctors in the Sunnybrook trauma center assumed that their jobs began when the human beings mangled on nearby Highway 401 arrived in the emergency room. Redelmeier thought it was insane for medicine not to attack the problem at its source. One-point-two million people on the planet died every year in car accidents, and multiples of that were maimed for life. “One-point-two million deaths a year worldwide,” said Redelmeier. “One Japanese tsunami every day. Pretty impressive for a cause of death that was unheard-of 100 years ago.” When exercised behind the wheel of a car, human judgment had irreparable consequences: That idea now fascinated Redelmeier. The brain is limited. There are gaps in our attention. The mind contrives to make those gaps invisible to us. We think we know things we don’t. We think we are safe when we are not. “For Amos it was one of the core lessons,” said Redelmeier. “It’s not that people think they are perfect. No, no: They can make mistakes. It’s that they don’t appreciate the extent to which they are fallible. ‘I’ve had three or four drinks. I might be 5 percent off my game.’ No! You are actually 30 percent off your game. This is the mismatch that leads to 10,000 fatal accidents in the United States every year.”

“Amos gave everyone permission to accept human error,” said Redelmeier. That was how Amos made the world a better place, though it was impossible to prove.

Michael Lewis is the best-selling author of Moneyball, Liar’s Poker, The Blind Side, and Flash Boys.

Excerpted from The Undoing Project: A Friendship that Changed our Minds by Michael Lewis. Copyright © 2017 by Michael Lewis. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.