My sister Camilla and I stepped off the passenger ferry onto the dock at Vineyard Haven, Martha’s Vineyard’s main port, with a group that had already begun their party. They giggled, dragging coolers and beach chairs behind them. We competed to see how many items of Nantucket red we could spot.

Not that we were wearing any. Camilla wore shorts with white long underwear underneath, and I wore beige quick-dry hiking pants. Both of us had on sneakers with long white socks. It was late June, perfect beach weather. The water sparkled. But we weren’t headed toward the ocean. We were there to hunt for ticks.

On the island, we hopped in a cab. Camilla looked longingly out the window as we passed the turns for the town beach and Owens Park Beach. The driver pointed out the location of the famous shark attack beach from Jaws. We drove on south to Manuel Correllus State Forest, an unremarkable park in the center of the island and the farthest point from any beach.

Deer ticks, or blacklegged ticks, are poppy-seed sized carriers of Lyme disease. We needed to collect 300 before the last ferry returned to Woods Hole, Massachusetts that night. We each unfurled a drag cloth—a one-meter square section of once-white corduroy attached to a rope—and began to walk, dragging the cloth slowly behind us as if we were taking it for a stroll. The corduroy patch would rise and fall over the leaves and logs in the landscape, moving like a mouse or a chipmunk scurrying through the leaf litter. Ticks, looking for blood, would attach to the cloth. Every 20 meters, we’d stoop to harvest them.

Tick collecting made it to Popular Science’s 2004 list of worst science jobs alongside landfill monitor and anal wart researcher. On cool days, though, sweeping the forest floor, kneeling to pluck ticks from corduroy ridges, the job became rhythmic. I felt strangely close to the forest. As I soon found out, the work got me closer to people, too.

The wilderness that we’ve feared, romanticized, and valorized is a fantasy.

Sometimes hikers would stop by, curious, then repulsed. They would want confirm the proper way to pull off ticks (with tweezers planted close to skin, perpendicularly), or to tell us about their diagnoses. Lyme disease isn’t like many of the diseases studied by my friends in the epidemiology department, where I was a doctoral student. No one talks about their grandmother’s syphilis infection, caused by Treponema pallidum, another spirochete bacterium.

But once people heard what Camilla and I were collecting, stories of brushes with ticks and family members’ diagnoses were shared freely. I quickly became the “tick girl.” When I started my dissertation I was preoccupied by the ecological question: How have humans altered the environment and triggered a disease emergence? By the time I finished, I realized that far more interesting were the rich and revealing tick stories shared with us along the way.

Illness makes us talk. “This is true of all forms of pain and suffering,” Arthur Kleinman, an anthropologist and physician at Harvard University, told me. We talk about illness “to seek assistance, care, and in part to convey feelings about fear, anxiety, or sadness.” In his book, The Illness Narratives, Kleinman writes that “patients order their experience of illness … as personal narratives.” These narratives become a part of the experience of being sick. “The personal narrative does not merely reflect illness experience, but rather it contributes to [it].”

The result is a peculiar togetherness. Once, a friend’s mom emailed that she’d just pulled off her first tick of the season, from her pubic hair: “I’m guessing it doesn’t it surprise you to hear, Katie, that you came to mind almost immediately when I discovered the little bugger? I’m afraid that ticks and you will be forever linked in my mind.” Naturally some took the motif too far. One creepy grad student thought that, because I was standing in front of a tick poster at an academic conference, I’d want to hear about the time he pulled a tick off his dick.

By dosing ourselves, we gain control.

The country singer Brad Paisley romances the tick: “I’d like to see you out in the moonlight / I’d like to kiss you way back in the sticks / I’d like to walk you through a field of wildflowers / And I’d like to check you for ticks.” I’m with Paisley here. Creeps aside, tick grooming is an act of love. My sister and I were diligent in the tick checks we gave ourselves and each other. Most nights, we’d pull off several at the campsite showers.

Tick stories mostly fell into a few categories. There were the boastful ones. On Washburn Island, a tiny island a few hundred yards off of Cape Cod, two hairy, fully-bearded park rangers, Steve and Steve, couldn’t be bothered to pull off their ticks. For most of the summer, they lived outside in tents and tarps and always had a few handfuls of ticks embedded in their skin. The Steves boasted that they’d each been infected with Lyme disease and babesiosis, a parasitic illness also carried by deer ticks, on and off for the last several years. Theirs was a backcountry machismo, as if their burliness made them immune to the intrusion of the forest twigs and ticks upon their bodies. Their symptoms, though, were presumably as real as anyone else’s.

The bulk of people’s reactions to the disease reflected a confused anxiety about boundaries. En route to a wedding in Easton, Connecticut, deep in Lyme country, someone found out that I was a tick girl and asked if they should be worried. The wedding was on a farm, an edge habitat where weedy species—mice, chipmunks, and robins—proliferate. Weedy animals include some of the best hosts for the Lyme disease bacterium. They can be infected with a tick bite and pass on the bacterium to the next tick that feeds on them, continuing unbroken chains of transmission. Deer, which are also hosts for ticks, thrive in these fragmented habitats, too.

I recited my usual tick check endorsement: Shower and check yourselves at the end of the night and you’ll be fine. The Lyme bacterium is only transmitted after the tick has been attached for two or three days. Still, when guests filled the lawn for corn hole and cocktails, I couldn’t help but notice all the cocktail dresses and open heels, ankle-deep in grass. The next morning, one woman told me she’d plucked three ticks from her ankle.

Worry bled to fear. On Cuttyhunk Island, the most remote of the Elizabeth Islands, a necklace of islands spilling off of southern Cape Cod, my sister and I were generously hosted by a woman I’ll call Susan, a self-trained student of the Lyme epidemic. “Ticks have become the bane of island existence,” Susan gravely told me shortly after I arrived. By 2010, everyone Susan knew on the island was taking doxycycline, the antibiotic most commonly prescribed for Lyme disease. She and her husband arrive in Cuttyhunk at the start of the summer season armed with bottles of it and take it prophylactically. Every time they pull off a tick, they take three doses, spread over 24 hours. This is not recommended by the CDC (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Doxycycline makes your skin sensitive to the sun, so their regimen makes it necessary to wear a hat and lots of sunscreen or stay inside.

Susan fenced in her lawn to keep out rabbits, which can host adult ticks, then raised the fence to defend against deer. “Our house is ringed with Damminix tubes, the yard fenced, grass mowed short, and still they turn up in the bed with us,” she told me. (Damminix tubes hold cotton infused with an insecticide that kills ticks.) We slept in her son’s room, crisp and nautically themed and lined with file cabinets full of scientific articles about Lyme disease epidemiology and ecology, local and national reporting on the epidemic, and printed email exchanges with epidemiologists and local politicians. Susan is now spearheading the island’s Tick Eradication Campaign. Her plan for eradication was ambitious, she admitted. But, she asks: “Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to say that you are stepping onto a tick-free island where a sunburn is the most dangerous health risk?”

The idea that the natural and human exist in separate realms is the very “trouble with wilderness,” the environmental historian William Cronon wrote in his 1995 book Uncommon Ground. The wilderness that we’ve feared, romanticized, and valorized over the last few hundred years, he says, is a fantasy:

[Wilderness] is quite profoundly a human creation—indeed, the creation of very particular human cultures at very particular moments in human history … Wilderness hides its unnaturalness behind a mask that is all the more beguiling because it seems so natural. As we gaze into the mirror it holds up for us, we too easily imagine that what we behold is Nature when in fact we see the reflection of our own unexamined longings and desires.

In the stories told by our doctors, our parks, and the CDC, ticks are invaders. To defend ourselves, we use insect repellent, clothing, and prophylactic antibiotics; fences, signs, and pesticides. “When it comes to pesticides, the environmental toxin par excellence, Lyme patients are often its greatest proponents,” writes Abigail Dumes, an anthropologist at Michigan State University. We prefer the risk posed by pesticides to the fear of Lyme, Dumes explained to me. They let us become actors instead of victims. By dosing ourselves with pesticides (or antibiotics), we gain control of our risks. Ticks, on the other hand are uncontrollable. “It’s difficult to live with the idea that there are enormous threats and many can’t be controlled,” Kleinman tells me.

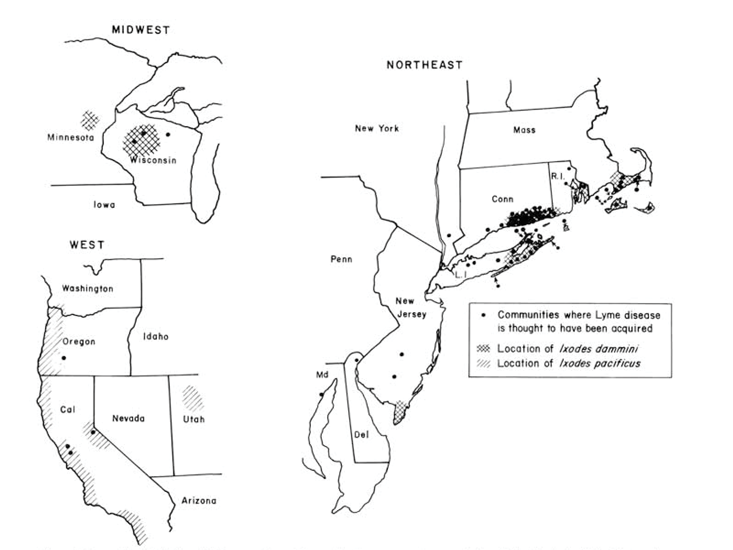

The problem is our defensive barriers aren’t working particularly well. Deer ticks are now established across 45 percent of United States counties. Their range has more than doubled in the last 20 years. Reported cases of Lyme disease have more than tripled since 1995 and the CDC estimates that more than 300,000 Americans fall ill each year. The story of tick-as-invader isn’t particularly helpful—or complete.

In November 1975, Polly Murray, an artist living in Lyme, Connecticut, contacted the Connecticut State Department of Public Health. Two of her children were sick with what doctors called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, a disease of joint pain. Their knees were so swollen that they were forced to walk with crutches. Several other neighborhood children had similar symptoms. Arthritis is rare in children. And it is not normally found in clusters. So Murray kept careful notes of her children’s symptoms and compiled a list of other sick children.

At first, doctors were dismissive. But Allen Steere, a young rheumatologist at Yale-New Haven Medical Center, was curious. He began to investigate cases in Lyme, Old Lyme, and East Haddam, quiet, wooded communities just east of the mouth of the Connecticut River. Through a surveillance “grapevine,” he found 51 residents—39 children and 12 adults—in a community of 12,000 suffering from unexplained arthritis. A quarter of patients also had erythema migrans, an expanding circular rash with a pale center, also called a bullseye. In some neighborhoods, 10 percent of children suffered from this unexplained arthritis. In 1977, in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism, Steere and his team named the set of symptoms Lyme arthritis. They called it “a previously unrecognized clinical entity.”

If anyone is an invader here, it’s us.

At that point, what caused the symptoms remained a mystery. The clustering of cases suggested the new disease was infectious, and the summertime peak of cases suggested it was spread by something in the water—picked up by swimmers—or by insects. Steere’s team tested his patients’ blood for dozens of viruses and bacteria. Nothing fit. In 1979, Steere and a colleague mapped out the first 512 cases of Lyme arthritis. The distribution of cases overlapped neatly with what was then the range of deer ticks. Many of Steere’s patients lived in wooded areas and had mentioned insect bites. But hundreds of ticks were tested and no pathogen was found.

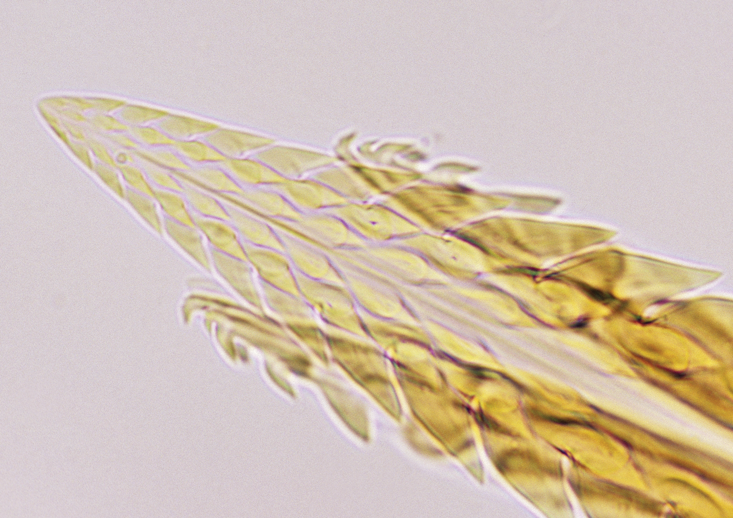

A few years later, William Burgdorfer, an entomologist at the Rocky Mountain National Laboratories, identified a new spirochete—a corkscrew shaped bacterium, capable of spiraling through the tissues of its hosts—in ticks collected from Shelter Island, a tiny island nestled between the two pointer fingers of Long Island. Sixty percent of ticks collected on the island carried the bacterium. Soon after, spirochetes were found in the blood of people suffering from Lyme arthritis. The Lyme disease bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, was named in his honor. It cycles silently in forests between ticks and a group of hosts, mostly small rodents and birds. From the perspective of the bacterium, humans are dead-end hosts and play no role in the spread of disease to new areas.

The modern history of the disease is relatively short: Just 40 years have passed since it was named. This can contribute to the sense that it is a new invader into our pristine neighborhoods and parks. But where did the bacterium come from? Was it truly new? And why did it first appear in a bucolic Connecticut suburb?

Spreading ticks and migrating bacteria leave no trace on the environment. Unlike pathogens that spread strictly from human to human (like measles), we cannot trace the history of the Lyme disease bacterium from the history of human epidemics. So, in 1990, biologists turned from medical records to museums. They sifted through old ticks in entomology collections at Harvard University and the Rocky Mountain National Laboratories, testing for bacteria. They found ticks infected with B. burgdorferi collected in the 1940s in Montauk Point and Hither Hills, parks near the Hamptons on the eastern tip of Long Island. Museum collections held no ticks before the 1940s.

That effectively doubled the known history of the disease. Then, researchers turned to the hosts themselves. They snipped ear punches from mouse specimens at the Smithsonian Museum, the Natural History Museum in New York, and the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Mice from Cape Cod in the 1890s turned out to be infected. Now the disease had a century-long history. Scientists studying Ötzi, the Tyrolean Iceman, stumbled upon in 1991 by hikers in the Italian Alps, have found that he was lactose intolerant, had intestinal parasites, severe atherosclerosis—and probably had Lyme disease. This meant the bacterium likely existed in western Europe 5,000 years ago.

To extend the history of the bacterium further back still, my advisors, Maria Diuk-Wasser and Gisella Caccone, and I turned to the 1 million letters of the bacterium’s genome. Pathogens evolve as they spread, and their genome carries a historical record of this development. By comparing pathogen genomes collected from different areas, we can build an evolutionary tree and a history of the pathogen’s spread. We can also tell how big the population of pathogens is now, and whether it is growing. This is the crux of phylogeography: Use evolutionary relatedness to answer questions about biogeography, the historic and spatial distribution of genetic diversity. A classic finding in the field, for example, is that the HIV epidemic originated in the French or Belgian Congo around the 1920s.

I began to chase bacteria from as wide an area and from as far back in time as possible. Biologists mailed me ticks in tiny tubes of ethanol from Michigan, Wisconsin, and Virginia. A Styrofoam container filled with dry ice and DNA samples of infected ticks collected across Canada was Fed-Exed to me. Old ticks were harder to come by. At the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, I pulled out drawer after drawer of taxidermied Peromyscus leucopus, white-footed mice, elegantly arranged in rows, with handwritten labels tied around their right ankles. Many were collected in the 1800s, when natural history museums were filled with hunting trophies. But the taxidermist had been tidy. The mouse skins had been cleaned of ticks. The oldest ticks I could find that were infected and had well-preserved DNA were from the early 1980s. Camilla and I added them to the 7,000 ticks from our summer harvest.

Finally, with 150 complete genomes in hand, my colleagues and I were able to extend the North American history of Lyme disease from a hundred years to many thousands. We drew a new evolutionary tree which showed that the bacterium likely originated in the northeast of the U.S., spreading south and west across North America to California. Birds likely transported it long distances to new regions, where small mammals continued its spread. Imprinted on the bacterial genomes was also a signature of dramatic population growth. As it evolved, it seemed to have proliferated.

Most interestingly, the tree was far older than we’d expected—at least 60,000 years old. Lyme was likely here in North America much longer than that, long before it was first named in the 1970s, long before humans first arrived in North America from across the Bering Strait (about 24,000 years ago), and long before the last glacial maximum, when much of North America was covered by an ice sheet (also about 24,000 years ago). If anyone is an invader here, it’s us. Our analysis also showed that the modern epidemic was not sparked by some new mutation that made the bacterium more readily transmissible. It was sparked by changes in ecology, most of which were man-made.

When colonists first arrived in New England, much of the area was forested. White-tailed deer were abundant. Deer ticks, whose distribution is closely tied to that of deer, most likely existed throughout much of the continent, too. Colonists pressed and pleated the complex fabric of New England’s forests, grasslands, and swamps into a starched blanket of fenced farmlands. Hunting and deforestation decimated deer populations. By the mid 18th-century, deer had almost entirely vanished. They never disappeared, though. Deer—and likely, deer ticks and B. burgdorferi—persisted in refugia, isolated pockets of southern Cape Cod and the far eastern tip of Long Island. Some deer populations were carefully cultivated. In 1698, hunters stocked the Naushon Island, one of the Elizabeth Islands (a few islands north of Susan’s Cuttyhunk) with deer. The island soon became a glamourous hunting destination and was purchased by the Forbes family in 1856, whose annual hunting party was attended by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Herman Melville, among others. The earliest record of a deer tick in the northern U.S. was on Naushon Island in 1926.

Beginning in the mid 1800s, farming gradually shifted westward and New England slowly reforested. But only shreds and slivers of forest were allowed to regrow. Deer populations rebounded and the animal spread across a transformed, suburban New England, one in which wolf predators had been exterminated, and where deer hunting was strictly limited. Ticks followed the deer, and B. burgdorferi followed the ticks. The sprawling grassy suburban lawn adjacent to a forest patch is the ideal Lyme disease habitat. The majority of tick-borne infections occur here because excellent hosts for B. burgdorferi also thrive in these manufactured edge habitats. More recently, climate change has been warming our winters, accelerating ticks’ life cycles and extending their range eight miles farther north each year.

The genetic and ecological history of the Lyme disease bacterium make it clear: Neither ticks nor the bacterium are invaders onto our pristine landscapes. They are the beneficiaries of an artificial and fragmented ecology created by the real invaders, us. Having sectioned and sliced the continent into a patchwork, we are confronted with the consequences. “Many of the individuals I spoke with during the course of my fieldwork moved to or remained in forested suburbs to be ‘close to nature,’ ” writes Dumes. “But ‘after Lyme,’ many described an experience of becoming ‘prisoners of their own paradise.’ ”

We’ve built structured domestic spaces on the periphery of the natural world to help us keep alive our fantasy of a wilderness that is pristine but kept at a safe distance. Ticks put the lie to that fantasy. They make us pay attention. They force us to notice and explore the freckles and spots of dirt on our ankles and our partners’ ankles. They force us to observe the spaces around us. They are rude reminders that there is no such thing as wilderness untouched by humans or humans detached from nature.

That’s a better story than tick-as-invader. This history doesn’t offer a tidy answer for how to stem the epidemic. But it shows us that our modern response to Lyme disease—to build more boundaries—echoes the impulse that created the epidemic in the first place. It’s not a just problem with Lyme. I defended my doctoral work earlier this year and am now studying another artificial boundary—the one between prisons and the free world—that is creating another epidemic: tuberculosis. My study sites have moved from Martha’s Vineyard to Brazilian prisons, but in a few ways, the new disease stories I’m encountering are alarmingly familiar.

Katharine Walter is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University.