The Simple Dutch Cure for Stress

Since reading this November post, by Alice Fleerackers, I haven’t been able to go for a jog in the wind without “uitwaaien” springing to mind. It is one of those difficult to translate words, from the Dutch, that means catching the breeze. Engaging in “uitwaaien,” Fleerackers explained, can have some surprising benefits for mental wellbeing, like helping us to destress and fend off cardiovascular disease. The word itself might act as a kind of psychological portal. By learning what words like “uitwaaien” mean, Fleerackers wrote, “we may be able to access feelings or experiences that we wouldn’t otherwise.” I, at least, can sense, on a gusty day, a boost in energy, or at least enthusiasm, when the Dutch word pops into consciousness on a run down New York City’s Riverside Park.

The English Word That Hasn’t Changed in Sound or Meaning in 8,000 Years

“Everything about a language is eternally and inherently changeable,” linguist John McWhorter has written, “not just the slang and the occasional cultural destination, but the very sound and meaning of basic words, and the word order and grammar.” It can be a delight, then, in view of that innate variability, to find a word—“lox”—that, in thousands of years, hasn’t changed, Sevindj Nurkiyazova wrote in Nautilus. She spoke to NYU professor of linguistics Gregory Guy, who is fond of the word. “The pronunciation in the Proto-Indo-European was probably ‘lox,’ and that’s exactly how it is pronounced in modern English,” Guy said. “Then, it meant salmon, and now it specifically means ‘smoked salmon.’ It’s really cool that that word hasn’t changed its pronunciation at all in 8,000 years and still refers to a particular fish.” The word “lox,” Nurkiyazova explained, was one of the clues that eventually led linguists to discover who the Proto-Indo-Europeans were, where they lived and why, within thousands of years, they expanded like no other human group that we know about in history.

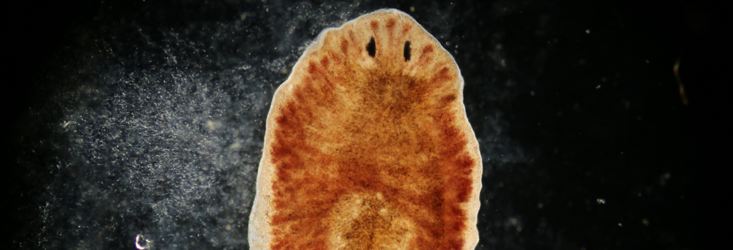

Memories Can Be Injected and Survive Amputation and Metamorphosis

In this piece, Marco Altamirano began by noting that researchers of memory have always occupied “one of the stranger outposts of science.” He goes on to show, with wonderful anecdotes and experimental details, why that is true. A scientist gained recognition as “young Frankenstein,” for instance, for causing a worm to grow a head where its tail had been. A butterfly, scientists found, could remember something from its life as a caterpillar. The results suggest where memories might reside—between neuronal synapses or within neurons themselves, imprinted in RNA. This scientific work, revealing that memories can be unexpectedly retrieved and moved, reminded Altamirano of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. The film, he wrote, posits that “memories are never completely lost, that it always remains possible to go back, even to people and places that seem long forgotten.”

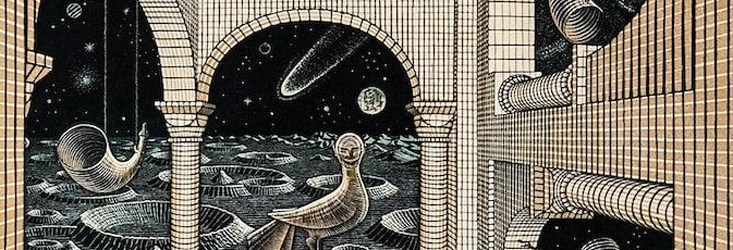

New Evidence for the Strange Geometry of Thought

Scientists have discovered, in recent years, that the brain has a sort of GPS, governed by “place” and “grid” cells, that help us orient in, and navigate, our surroundings. In his 2018 Nautilus feature, “The Surprising Relativism of the Brain’s GPS,” neuroscience grad student Adithya Rajagopalan explained how, according to new data, “place” cells actually create our sense of space with a kind of in-built relativity between position and environment, as opposed to an absolute position in a Newtonian sort of space. It was fascinating and, when I saw researchers suggest, in Science, that “place” and “grid” cells play a role in our thinking—creating a conceptual space for our thoughts—I knew Rajagopalan could write well on the topic. The piece begins by introducing the Swedish philosopher of conceptual spaces in the brain, Peter Gärdenfors, and goes on to explain why Gärdenfors’ theory “highlights a fruitful path, not only for cognitive scientists, but for neurologists and machine-learning researchers” to follow on their journey to illuminate the nature of thought.

The Case for Professors of Stupidity

This piece, which I wrote in the wake of International Holocaust Day, has depressing new resonances due to the bewildering recent incidents of anti-semitism, in the United States and abroad. What’s going on? Well, Bertrand Russell’s answer, as he watched Nazis and their sympathizers transform Germany in 1933, was that stupidity had triumphed. A “fundamental cause of the trouble,” he noted, “is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” This quip might put you in mind of the famous Dunning-Krueger effect, whereby the incompetent are unable to recognize their incompetence and, as a result, rate their abilities well above what’s warranted. In their work, psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger have paid homage to Russell’s insight: Stupidity shapes history. If that’s true, shouldn’t stupidity be a formal area of study? Complexity theorist David Krakauer, I noted, has said so. “It would just be embarrassing,” he said, “to be called the stupid professor.”