You might not find ants and termites tasty, but plenty of animals have throughout evolutionary history: It turns out that ant-eating mammals have evolved independently more than 12 times over the past 66 million years. But how did species who exclusively dine on termites, ants, or both emerge so many times?

To clear up this mammalian mystery, researchers traced the evolutionary history of these long-snouted, ant-and-termite-eating creatures, known as myrmecophages. They suggest that the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period paved the way for myrmecophages, which include anteaters, aardvarks, pangolins, and some armadillo species, according to a paper recently published in Evolution. As the sun set on the Cretaceous, non-avian dinosaurs, among many animals and plant species, disappeared, and the Earth began to transform into an ideal ecosystem for ants and termites.

“While some species evolved defenses to avoid these insects, others took the opposite approach—if you can’t beat them, eat them,” said study author Phillip Barden, an evolutionary biologist at New Jersey Institute of Technology, in a statement.

Today, the combined biomass of termites and ants is greater than that of all living wild mammals, and there are 20 surviving species of “true” hard-core myrmecophages, including aardvarks, pangolins, and giant anteaters. They have signature features to expertly dine on these insects, such as long front claws and tongues for digging and slurping, and vacuum up hundreds of thousands of the insects per day.

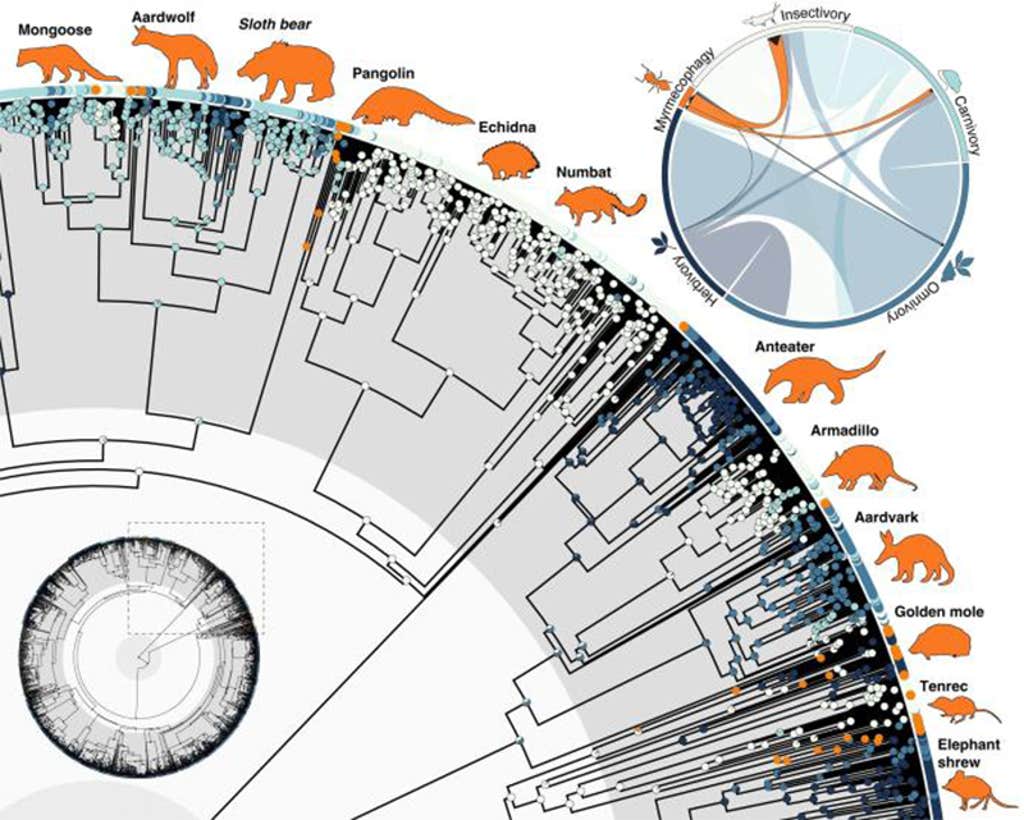

To learn when—and how frequently—such characteristics evolved, Barden and his co-authors examined a vast trove of data on the diets of more than 4,000 mammal species.

After placing these mammals on a family tree, the researchers harnessed statistical models to piece together their ancestral diets. This revealed that myrmecophagy cropped up more than a dozen times throughout a variety of mammal lineages. Even though evolution arrived at ant-eating repeatedly, it’s a pretty uncommon lifestyle in terms of how many mammal species actually partake: Eight of these myrmecophagous lineages are each represented by just one distinct species.

All ant-eating mammals evolved from carnivores or insectivores, the team learned. They also noted that myrmecophagy evolved more than once in each of the major mammal groups—but some seemed to be more “evolutionarily predisposed” for ant and termite sustenance.

Unlike diet trends among people, researchers noticed that myrmecophagous mammals tend to stick to this habit—except for a genus of elephant shrew, which eventually switched to omnivory.

And while they’re pretty picky about food, myrmecophages might have an advantage in a warming world. “In some ways, specializing on ants and termites paints a species into a corner,” Barden said. “But as long as social insects dominate the world’s biomass, these mammals may have an edge—especially as climate change seems to favor species with massive colonies, like fire ants and other invasive social insects.” ![]()

Lead image: adamardn / Shutterstock